Of Sandstorms and Nuclear Tests

February 27, 2012

Henryk Szadziewski, Manager, Uyghur Human Rights Project

The Uyghurs in Kashgar are used to sandstorms. The city’s location in an oasis on the edge of a vast desert makes it a reality of life there. When the wind picks up far out to the north and east and arrives in Kashgar with a thump, Taklamakan sand squeezes through windows and scatters all over the homes of the city’s residents. As a young English language teacher at Kashgar Teachers College, sandstorms were as far as anyone could get from rain sodden England, where I grew up; however, in the time I had lived in the city, I got used to sweeping up small piles of sand in my apartment.

On one occasion, I woke in the morning to a particularly fierce sandstorm. I could hear the repeated slamming of unlocked doors and the whooshing sound made by the poplar trees when the wind surged through them. As I looked out of the window, the only sign of human life was the Kyrgyz yoghurt seller battling to stay upright as she was buffeted by strong blasts of air racing between the apartment blocks that housed the college’s staff. As the morning went on, and I prepared for my afternoon class, the wind never relented. The natural light became poorer and poorer to the extent that I had to put on a lamp to be able to see what I was doing.

With no indication that classes were cancelled, I set off in the afternoon to teach. This particular class had been difficult to manage; half of the students were Uyghur and the other half Han Chinese, and they regularly bickered over their many differences. When I arrived at the classroom, only a handful of students were present. I asked about the weather saying that it seemed especially severe. There was silence. One of the Uyghur students spoke up and said, “This is what happens after the Chinese government has tested a nuclear weapon.” Now it was my time to be silent. A Han Chinese student chastised the Uyghur in Mandarin with, “Don’t tell him that! He’s a foreigner.” Another Han Chinese student told me in English that the unusual weather was just a sandstorm and nothing more. I taught the rest of the class under an atmosphere of tension and then went back home like everyone else. In the repressive political environment of Kashgar, nothing more needed to be said.

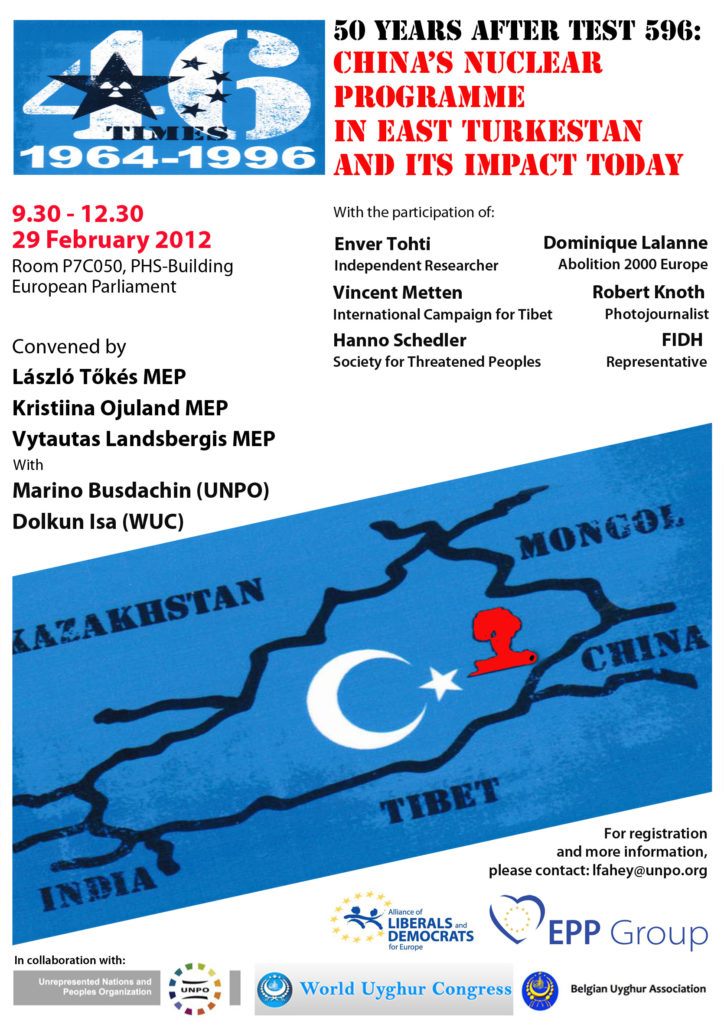

On February 29, 2012, the World Uyghur Congress, a host of MEPs, the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization and the Belgian Uyghur Association will convene a conference on the devastating effects of China’s nuclear testing at Lop Nur. The conference, ’50 Years After Test 596: China’s Nuclear Programme in East Turkestan and Its Impact Today’, presents a range of experts to testify on an issue that has unjustly received scant attention and been contained by the silence I experienced in Kashgar. One of the experts is Uyghur doctor Enver Tohti, who at great personal risk helped to raise awareness of the issue’s urgency in the documentary Death on the Silk Road.

Between 1964 and 1996, the People’s Republic of China conducted 46 nuclear tests in East Turkestan, the homeland of millions of Uyghurs. These were the largest series of nuclear tests in the world ever to be conducted in an inhabited area. Some of the bombs were 300 times more powerful than the one exploded in Hiroshima.

23 of the tests conducted by the government of the People’s Republic of China were atmospheric, with nuclear fall out reaching as far as Europe. In addition, research indicates that radiation from the 23 tests conducted underground has reached countries as far away as Japan.

The effect the 46 tests have had on the Uyghur people and their land remains largely undocumented. What is known is that rates of cancer in the region are higher than in the rest of China and cases of leukemia, malignant lymphoma and lung cancer are all elevated. Approximately 8 out of 10 children in the villages near to the four nuclear testing sites at Lop Nur are born with cleft palates, and congenital deformities such as enlarged stomachs are common. Besides the tragic human consequences, environmental concerns over contamination of water, air and land in inhabited areas loom large. Compounding the state of affairs are allegations by former Soviet scientist Ken Alibek that a grave accident occurred at a biological weapons plant near Lop Nur in the 1980s.

In the face of contrary evidence, the Chinese government has denied the existence of far-reaching and ill effects arising from its 46 nuclear tests at Lop Nur. It has routinely denied access to independent researchers investigating the effects of the tests, while at the same time suppressing any internal documents that point to the existence of a human and environmental tragedy. The conference in Brussels is a huge step in ending the silence.