Art on Uyghurs in NYC Highlights China’s Information Control

December 7, 2012

Greg Fay, Manager, Uyghur Human Rights Project

To inaugurate Forever & Today’s gallery opening in New York’s Chinatown in 2008, the artist collective Slavs and Tatars made a poster: “Keep Your Majorities Close But Your Minorities Closer.” Slavs and Tatars focuses on Eurasia from the Berlin Wall to the Great Wall of China, and the poster refers to government control across the region including the Uyghur homeland, East Turkestan.

Two exhibits in New York last month highlighted China’s strict control over information about Uyghurs in East Turkestan, even in relation to tight control on the Han majority. First, a new work by Slavs and Tatars at Forever & Today called “Never Give Up the Fruit” shared a Uyghur folktale that the government has in fact rewritten. Second, an exhibit sponsored by China’s government at the Asian Cultural Center called “Beautiful Xinjiang” showcased the beauty of East Turkestan by glossing over China’s religious and political repression of Uyghurs and other indigenous people there.

In “Never Give Up the Fruit,” Slavs and Tatars creates an allegory for Iparhan, or Xiang Fei in Chinese, the Fragrant concubine. 30 blown glass Uyghur koghun melons hung from wooden planks forming the Chinese characters, 掩饰, or dissimulation. According to legend, as Slavs and Tatars’ explains, dissimulation figures heavily in Iparhan’s story. She hides daggers up her sleeves after she is kidnapped to be the concubine of China’s Qianlong emperor, even as she attracts him with her sweet melon scent. Loyal to her homeland, Iparhan “never gives up her fruit” to Qianlong. For more images of the exhibit, see Chennie Huang’s excellent review.

In fact, the legend’s history is contested, as Jim Millward outlines in his seminal 1992 article, “A Uyghur Muslim in Qianlong’s Court“. The tale of a fragrant, exotic beauty coming to Beijing against her will and plotting assassination of the Chinese emperor originates in Chinese dramatizations from the early 20th century. Since the 1980s, however, the Chinese government has forbidden this tale as a “separatist” narrative, and remade Iparhan as a loyalist to the Chinese state, as delineated on this government-sponsored website. Forever and Today’s windows, facing out to Chinatown, spread the tale of resistance, though the exhibit could have had a more explicit focus on the repression of the original folktale.

By contrast, “Beautiful Xinjiang,” which ran at the same time in New York, was tucked away in a large office building near Grand Central Station. Hosted by the Asian Cultural Center, an affiliate of SinoVision TV, China Press Newspaper, SinoAmerican Times, and Sinovision net, which aims to serve the overseas Chinese community, the space looked more suited to hosting an official ceremony, like the promotional video on China Daily’s Youtube Channel. The exhibit was sponsored by China’s State Council’s Overseas Chinese Affairs Office and New York consulate, and was visited by a number of government officials according to China Daily.

Whether “Beautiful Xinjiang” was meant for public consumption or simply a photo-op for publicity, the message of the exhibit was nevertheless quite clear. The collection consisted of nearly 70 images accompanied by captions describing development, minority culture and religion, and natural resources. The exhibit perpetuated a number of myths that mask the government’s repression of the Uyghurs and other indigenous people in East Turkestan.

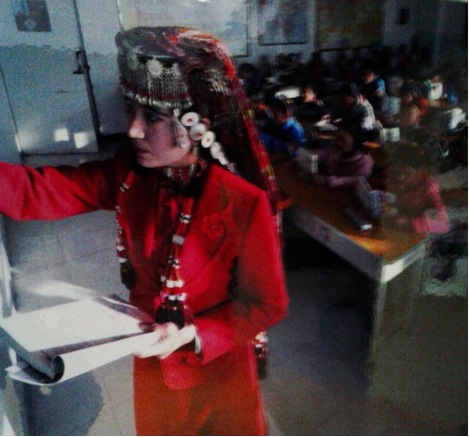

The thesis of the exhibit was perhaps best invoked in the following caption: “Many ethnic groups live in Xinjiang and they learn to live harmoniously together through learning from one another, while at the same time maintaining their own ethnic languages, culture, way of living and traditions.” Accompanying the caption is the image at right of, “a Tajik female teacher teaching in Han Chinese.” In fact, China’s “bilingual” education policies, which force Uyghurs and other indigenous people in East Turkestan to study in Mandarin from preschool to university, are highly contested and perceived as an attack on their own languages. A Tajik woman teaching in Han Chinese may serve as evidence of development to an audience of overseas Chinese, but it masks an important debate about language rights and bilingual education.

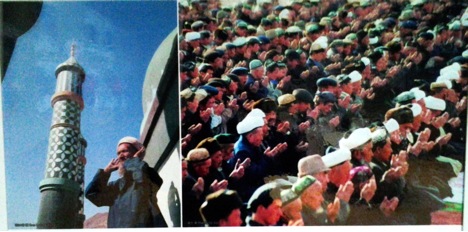

The exhibit’s depiction of Islam goes even further to mask China’s repressive policies toward Uyghur culture. A picture of a veiled woman is captioned, “Due to the influence of Islam certain places in southern Xinjiang still have the tradition of females wearing the hijab (a veil) which is usually black or brown.” That China frequently forbids the wearing of the veil is not mentioned, a frequent omission in China’s rhetoric. Yet another image of Muslim worshippers appears beside it:

The caption states, “The population of Muslims is approximately 11.3 million and accounts for about 50% of the entire population in Xinjiang. There are 24,300 mosques in the region.” Yet again, these cheerful statistics mask bleak realities. First, just as veils have been targeted for women, beards such as that worn by the man on the left have also been targeted, particularly during Ramadan this year. Second, the number of mosques does not reveal the strict religious prohibitions enforced, like forbidding worship for those younger than 18 and state control of imams. Finally, the population statistics listing Muslims as half of the population glosses over a history of government-sponsored Han population transfer to reduce the percentage of indigenous Muslims. The Han population, nearly half of East Turkestan today, was only 6% in 1949.

By pushing propaganda at the Asian Cultural Center that publicly celebrates minority culture in East Turkestan, China’s government hopes to deceive its audience of mostly overseas Chinese about repressive policies there. A similar event took place last month in Japan and RFA’s Uyghur service reported that local Uyghurs were even pressured to participate. This deception of the majority about repression of minorities is a clear example of keeping “your majorities close but your minorities closer.” One can hope that some visitors to the Asian Cultural Center passed by Forever & Today’s gallery also, for a reminder of the legacy of resistance and dissimulation in East Turkestan.