Forced Allegiance: Reflections on Flag-raising Ceremonies and National Anthems in Britain and East Turkistan

September 30, 2025

A UHRP Insights column by Dr. Henryk Szadziewski, Director of Research, Uyghur Human Rights Project

Growing up Polish in Britain

In schools across Britain, where I grew up, “assembly” was a normal part of schooling. At least once a week, students and teachers would gather in a school hall for routine announcements, commendations or reprimands of student behavior, and perhaps a short talk. One school assembly I joined when I was ten years old has stayed with me.

My hometown is in the English Midlands. Manufacturing, predominantly in the boot and shoe industry, was once the main economic activity. The town’s industrial history attracted migrants from across the globe, including my parents. At my school, the classrooms reflected this history: the children of Barbadians, Jamaicans, Gujaratis, Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, Poles, Italians, Irish, Ukrainians and Hong Kongers sat side by side.

On one particular day, we were all neatly seated cross-legged in rows on the floor of the school hall, waiting for assembly to begin. The music teacher sat at a weathered piano in the corner, while the deputy headmaster, dressed in a blazer and stiff-collared shirt, stood in front of us. The first bars of “God Save the Queen” suddenly rang out. Only some of the students stood up. As the music continued and we remained seated, the deputy headmaster’s face flushed red with anger. He bellowed at us that we should all stand up and respect the British national anthem. Startled, and confused, we did as he asked. For the next fifteen minutes, we practiced: sitting down when told, standing at the cue of the piano, over and over again.

The incident has drawn mixed reactions whenever I recount it. Some friends and colleagues insist it was right to teach a group of immigrant children to identify with their new country. Others are alarmed, describing it as forced patriotism. Personally, the exercise did not instill loyalty in me. The rage of the deputy headmaster, the piano teacher’s relentless recital, and my mechanical sitting and standing left me skeptical about what it means to be British.

That skepticism was shaped in part by the privilege of my circumstances. In Britain, I had the space to question nationalism, to laugh at the absurdity of the episode, and to reject the idea that loyalty could be drilled into me. That condition is key, as that privilege is absent for many communities around the world. For Uyghurs in East Turkistan, enforced patriotism, in the form of state flag-raising ceremonies, is not a curious memory of schooldays, but part of a system of coercion and punishment designed to eliminate dissent and reshape identity.

An Uyghur Testimony

In marking the People’s Republic of China’s National Day on October 1, I want to share the words of an Uyghur I spoke to about four years ago. The individual, who was detained in a concentration camp, released, and later escaped to the United States, described the nature of flag-raising ceremonies in East Turkistan. Their testimony underscores the difference between a ritual meant to encourage belonging and one imposed to erase difference.

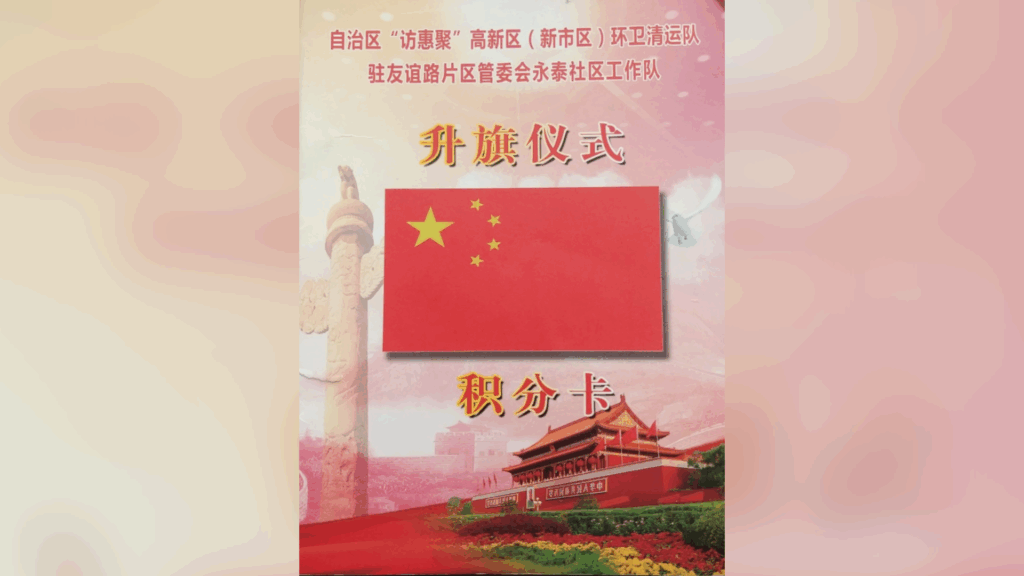

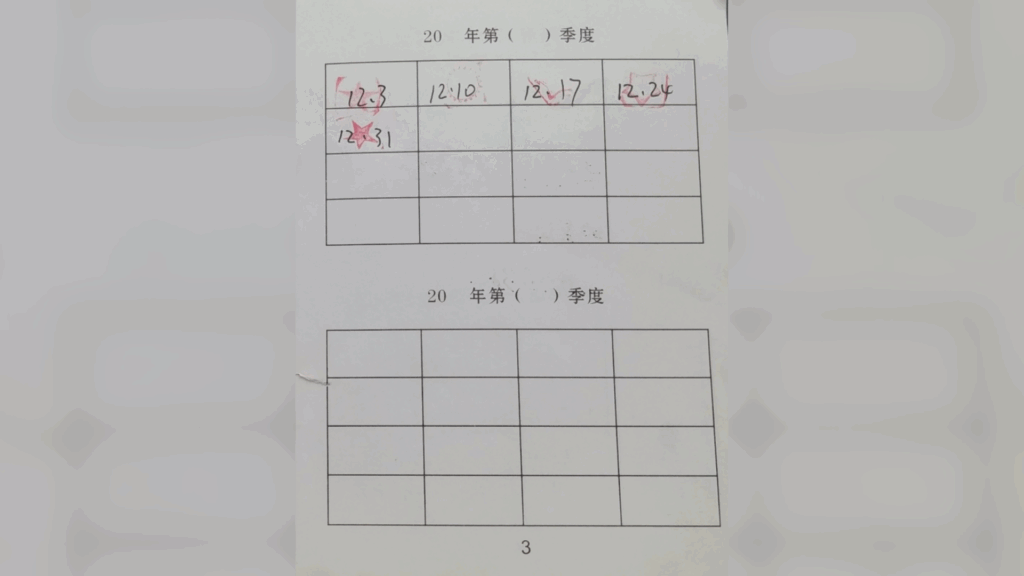

I was released from a camp in June 2018. Soon after, I got a booklet to record my attendance at flag-raising ceremonies from the shequ [neighborhood residents] committee, who handed these booklets out to everyone in our community, not to Han Chinese, only to Uyghurs.

Before 2017, we didn’t have to attend flag-raising ceremonies. After 2017, things changed, the shequ leadership, which was now mostly Han Chinese, made participation mandatory. Uyghurs had no power and everything was done in the Chinese language.

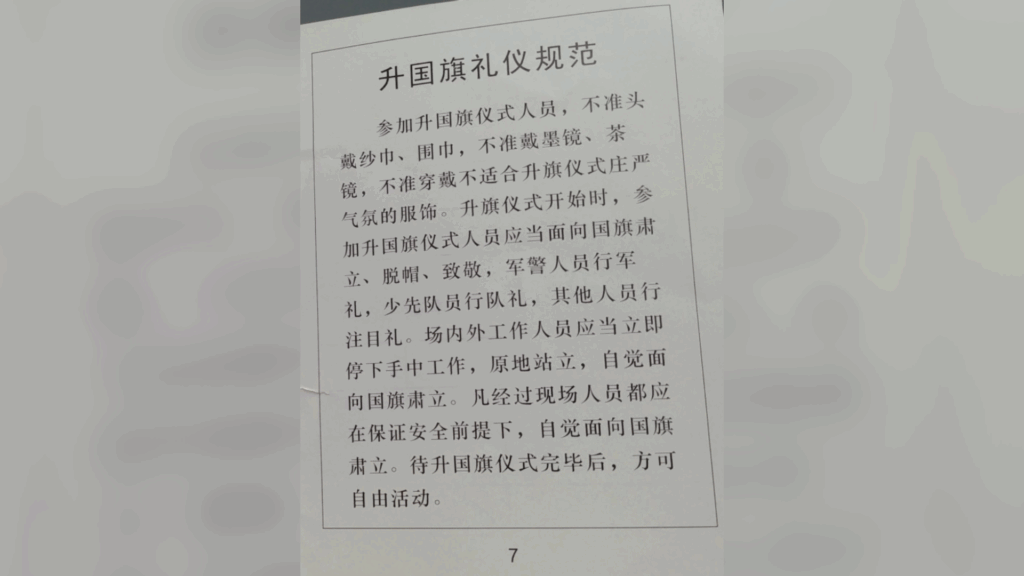

The flag-raising ceremonies were held in front of the shequ committee office. They were usually once a week from 8 to 10 a.m., and on special days like National Day and May 1. If it was a school holiday, we had to take our children with us. The weather never mattered, hot or cold, everyone had to attend.

On the way to the ceremonies the Chinese laughed at us and said things like, ‘show you love your country.’

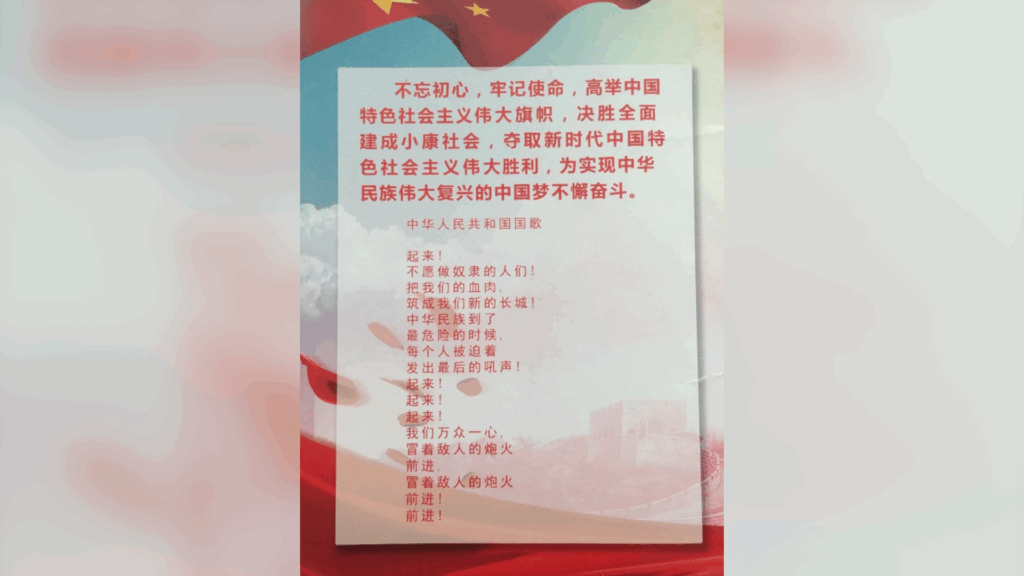

The ceremony itself always began the same way: the Chinese anthem played over loudspeakers and the flag was raised [see a video of a ceremony].

We were forced to memorize the national anthem and sing it. Some people wrote the pinyin on paper to help them pronounce the Chinese characters. In Ürümchi winters are very cold and summers are very hot, but everyone had to take off headwear during the ceremony, even the sick and the old.

At each ceremony five people were required to read aloud an essay they had written thanking Xi Jinping, the Chinese Communist Party, and the great life Uyghurs have in China.

After the readings, the shequ committee leader gave us warnings and advice. It was scary as they talked about the consequences of our actions, such as detention in the camps. We were also told not to contact relatives abroad. Religious content on our phones was absolutely forbidden.

The shequ committee leader also told us it was important to be united, to be one family. They warned about the activities of external forces trying to split China. If we ever saw this kind of behavior, we should immediately report it. Interethnic marriage was encouraged. The leader said Uyghur women who married Han men and contributed to ethnic unity would get ‘benefits.’ Xi Jinping’s speeches were distributed to the attendees at this time.

The ceremonies were an opportunity to apply rewards and punishments based on attendance. If your attendance dropped below 90 percent there were consequences. If attendance was above 95 percent, you received a reward certificate.

After the ceremony finished, we went, one by one, to get a stamp in our booklet.

It was clear to me what the flag-raising ceremonies were for: to make Uyghurs into Chinese, to make us serve China. We were treated like children. I often couldn’t listen during those sessions but the propaganda wasn’t limited to the ceremonies. It was on loudspeakers in the streets and on buses; everywhere you heard it. We were all sick of it.

Blurring National Unity with Uyghur Identity

This testimony illustrates how ordinary rituals of patriotism, such as flag-raising and anthem singing, take on an entirely different meaning when enforced under conditions of surveillance, discrimination, and fear. Besides serving as the lowest tier of administration, performing bureaucratic and social services, shequ committees (社区委员会) are tasked with implementing regulations and ensuring compliance. In addition to shequ committees, employers also conduct flag-raising ceremonies, in some cases those employers are tied to state sponsored forced labor.

The booklet system and mandatory attendance demonstrate the extent to which the Chinese authorities regulate Uyghurs’ social and cultural lives. Every appearance is recorded and loyalty is not simply expected but documented through stamps and essays of gratitude. Further, residents are encouraged to report on their neighbors for non-attendance.

This monitoring reduces Uyghurs to the status of children, stripped of agency and treated as in need of correction. They are instructed when to stand, when to sing, when to remove their headwear, and when to denounce others. The comparison with ordinary school rituals is striking, immigrant children and Uyghurs are seen as outsiders, yet in East Turkistan the stakes are not embarrassment, but personal safety and collective identity.

Restrictions on contacting relatives abroad, punishments for religious expression, and incentives to intermarry all worked toward the same goal: to recast Uyghurs as assimilated Chinese citizens while suppressing the markers of their distinctness. Even the timing of the ceremonies themselves serve to obstruct religious expression. For example, Radio Free Asia Uyghur Service reported how flag-raising ceremonies were scheduled to disrupt prayer.

Whereas my own childhood memory of being drilled to stand for the British national anthem in school carried no serious consequence, Uyghurs face real punishments by the state for noncompliance, from bureaucratic obstacles to detention in camps. The repetitive, ritualized nature of the ceremonies conditioned behavior through intimidation.

In contrast to Chinese state media propaganda of a people now cleansed of “separatism,” in 2024, Radio Free Asia’s Uyghur Service noted that flag-raising ceremonies remain widespread in East Turkistan.

Allegiance and State Power

Reflecting on my own childhood, I recognize parallels while acknowledging the great difference in experience. I could question the patriotic ritual and mock it openly to others. I was also in school. The space to resist was available.

For Uyghurs, that space is closed. The state compels attendance at ceremonies and enforces broad community participation. The iterative nature of these events, week after week, year after year, creates the conditions in which people internalize the power of the Chinese state.

National days, flag-raisings, and anthems are not unique to China. Many countries, including Britain, use rituals of patriotism to encourage national pride. What makes the Uyghur case distinct are the conditions under which it is carried out. For Uyghurs, these ceremonies are not celebrations of belonging but reminders of exclusion. There are no choices over identity and allegiance.

Ultimately, enforced displays of patriotism lead to doubt. In my childhood, the absurdity of being drilled to stand on cue left me skeptical of nationalism. For Uyghurs, the absurdity is coupled with coercion, punishment, and fear. For them, China’s National Day is not a holiday but a day to feel the full weight of state power.