Peeling Back the Layers: Understanding Responsibility from Top to Bottom in the Uyghur Crisis

September 5, 2023

A UHRP Insights column by Peter Irwin, Associate Director for Research and Advocacy, Uyghur Human Rights Project

What do we mean when we say that the “Chinese government” is committing genocide and crimes against humanity in East Turkistan?

We often reach for easy descriptors to allege responsibility. Chinese government, Chinese officials, Chinese Communist Party; these power-holders are certainly responsible for what’s happening in the Uyghur region, but how helpful is this framing for understanding the mechanics of repression and atrocities from the ground up?

We know plenty about the laws, regulations, and policies designed at the top and implemented at the bottom, but comparatively less about who is actually responsible throughout the chain of command.

The “Xinjiang Papers” uncovered how mass detention and its associated policies were crafted and carried out with a high degree of coordination and direction from the central government—all the way up to former regional Party Secretary Chen Quanguo as well as Xi Jinping himself. And the Qaraqash List showed how civilian officials traced out family ties and recorded “reasons for detention” at the neighborhood level.

For its part, Tahir Hamut’s new book, Waiting to Be Arrested at Night, offers a vivid, personal, account of what it was like to navigate an increasingly hostile environment for Uyghurs in East Turkistan. The book does a masterful job putting the reader squarely in the shoes of someone just trying to get by—the tortured decisions, the impossible compromises, and the necessity of escape.

Individual stories told within a larger context helps us comprehend the mechanisms of authoritarian regimes and the tactics they employ to manipulate and control their citizens.

At the same time, it’s critical to understand who does the “enforcing” on the ground—the vehicles for the “Chinese government” policies we know so well. A clear understanding of these dynamics, past and present, helps broaden the scope for justice and accountability down the road.

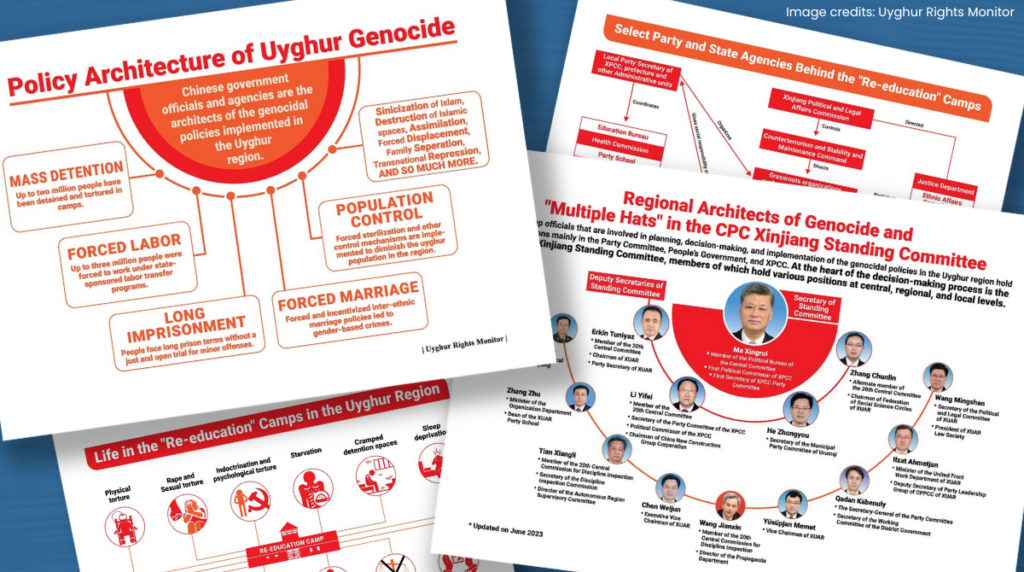

The Uyghur Rights Monitor (URM), a collective of Uyghur researchers, has set out to do just that—to better identify perpetrators down to the local level in two recent reports focusing on agencies involved in mass detention and the “Architects of the Uyghur Genocide.”

Which government department, for example, so fastidiously examines Uyghur films, books and or poems so that Tahir increasingly self-censors? Who is responsible for dispatching a dozen police to a restaurant where Tahir gathers with fellow poets and writers? Who are the officials assigned to take Uyghurs in the middle of the night from their homes?

The government agencies, offices, and bureaus that implement top-down directives are the source for why Tahir—and millions more—are faced with impossible limitations on their freedom of movement, expression, and even thought. Consideration of the legal notion of “superior responsibility” within this context may also be useful when thinking about accountability.

The Chinese government is not, after all, just some faceless, monolithic entity, meting out punishment from on high. There are countless layers of responsibility that need to be peeled back to better understand the architects—and architecture—of atrocities.

Tahir Hamut’s personal narrative humanizes the crisis, providing insight into the individual effects of government policies, and URM’s research provides a valuable framework for understanding how top-down policies are implemented on the ground. Together, they contribute to a much more holistic understanding of the Uyghur crisis.