Uyghur Deportations from Thailand Part of a Decade of Betrayal

July 8, 2025

A UHRP Insights column by Peter Irwin, Associate Director for Research and Advocacy

On July 8, 2015, Thai authorities shackled and hooded at least 109 Uyghur men then placed them on a plane bound for China. Chinese state media released footage showing the men surrounded by armed police on the flight.

The message was clear: there would be no sanctuary for Uyghurs fleeing persecution, even outside of China’s borders.

That moment, ten years ago, marked a chilling escalation in what human rights experts now recognize as transnational repression (TNR). China had long sought to control Uyghurs outside its borders, but the deportation from Thailand demonstrated how far its reach could extend—and how willing certain governments were to cooperate.

What followed was a decade of cruelty and neglect. While the men were taken back to China, dozens more remained in Thailand’s immigration detention centers, languishing in squalid facilities without access to lawyers or proper medical care.

At least five Uyghurs died while in detention from 2014 to 2024, including a newborn baby in June 2014, and a four-year-old in December 2014 who earlier became sick with tuberculosis and was not provided with adequate care. In 2018, a 27-year-old Uyghur man named Bilal, who complained of headaches following a prison beating after an escape attempt, died in detention. In February 2023, a 49-year-old detainee named Aziz Abdullah died of pneumonia, and just two months later, another detainee, Muhammad Tursun, died reportedly of respiratory and circulatory failure.

Years dragged on with no movement despite increasing calls for resettlement.

A February 2024 letter from a group of UN experts to the Thai government said that the Uyghurs’ continued detention may have violated international law, including prohibitions against torture, arbitrary detention, and the right to a fair trial.

A 2024 investigation in The New York Times Magazine by Nyrola Elimä and Ben Mauk found that detainees were living in deteriorating conditions in the Thai facilities. One detainee said he had not seen the sun in 10 years.

An investigation in May 2024 by The New Humanitarian by Jacob Goldberg found that UNHCR, the UN’s refugee agency, rebuffed requests from the Thai government to assist the remaining 48 Uyghurs in detention.

Internal memos showed that UNHCR’s Thai country office decided in late 2020 that “taking pro-active steps before the Thai authorities engage UNHCR officially is not advised.” Another memo even warned of a risk of “negative repercussions on UNHCR’s operation in China” and of “funding/support to UNHCR,” including for staff and multi-million dollar projects if the agency intervened.

The lack of sustained attention to the men, insufficient support for resettlement, and an intransigent Thai government meant the risk of deportation grew.

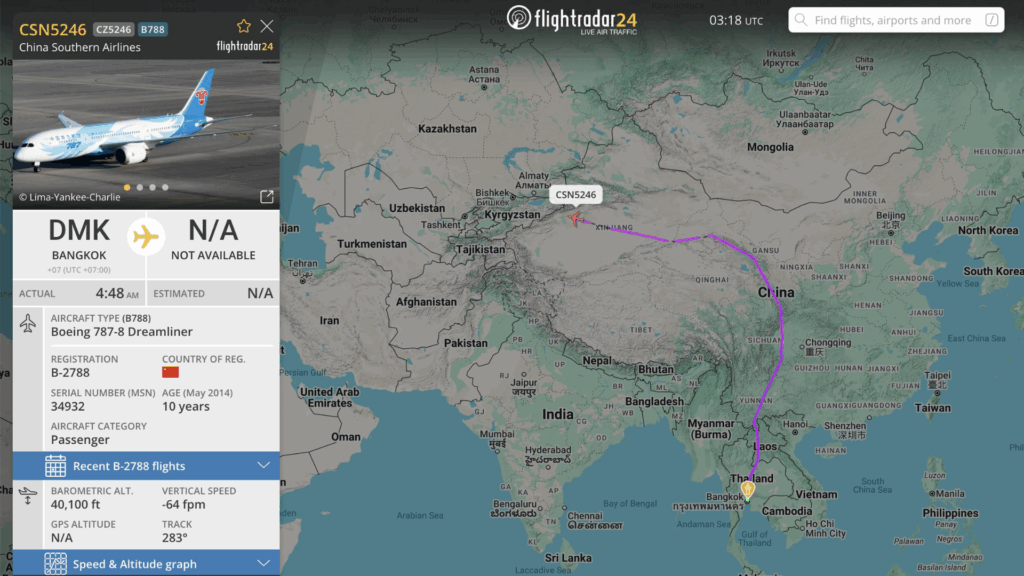

Likely seeing an opportunity to act during the US presidential transition period, Thailand began preparing to deport the remaining men in late 2024. Despite last-minute pleas from UN human rights experts, lawmakers, and activists, in the early morning hours of February 27, 40 Uyghur men were removed from their detention center in central Bangkok and were loaded into vans with their windows blacked out. The men were driven to the airport and deported back to China on a flight to Kashgar.

A flurry of after-the-fact condemnations were swift, including from the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and UNHCR. But their statements read more like a list of routine platitudes from agencies unwilling to do the real work to fulfill their own mandates to protect the men.

It’s easy to imagine staff pulling these pre-written statements up, dusting them off, changing a word or two, and publishing them moments after what they saw as an inevitability, acting as if there was nothing they could have possibly done to intervene.

A month after the deportations, the US government announced visa sanctions on Thai officials, but it’s difficult to believe these will result in any real change, particularly given the administration’s perspective on the worthiness of refugees and asylum seekers around the world.

Greater contributions to UN agencies from rights-respecting governments would help alleviate an increasing dependency on funding from governments that flagrantly violate international law.

The US government has proposed the exact opposite, and is acting on its pledge to dramatically cut funding to UN agencies. Cuts in contributions to UN agencies like UNHCR will only exacerbate a situation where staff already feel constrained, as well as reluctant to act in ways that might irritate or offend the Chinese government, who will now be the real winner.

The result will be swifter deportations of Uyghurs around the world, more silence from agencies tasked with protecting them, and more impunity for the Chinese state as it extends its repression far beyond its borders.

Nate Schenkkan, who worked with a team at Freedom House reporting on transnational repression (TNR), recently argued, “[I]n every other possible way the government has destroyed the infrastructure that was being built to make the U.S. a leader in counter-TNR policy and to support other democracies in tackling the problem.”

As a result, other democracies need to step in to fill the gap left by a retreating United States. If Washington no longer intends to lead, at least for now, on countering transnational repression, then it falls to other rights-respecting states to increase funding for UN agencies, push for institutional accountability, and offer resettlement pathways for those most at risk.

As a sign that protection is still possible where the right amount of political will exists, Canada quietly resettled three of the remaining Uyghur men in April 2025 from Thailand. The men held Kyrgyz passports, likely a factor in easing their resettlement.

For what it’s worth, the UN has also made some progress in the last year to address TNR. Irene Khan, the Special Rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression released a report in 2024 adopting the framework of TNR to address how governments target journalists who have fled their countries. In June 2025, OHCHR released a new fact-sheet identifying transnational repression as an issue that deserves attention, and providing guidelines on how states and other actors can respond.

Ten years on, the Uyghur deportations from Thailand stand as a damning symbol of the international community’s failure to respond to China’s expanding campaign of transnational repression. The world has watched, year after year, as governments capitulate, UN agencies retreat, and the rights of stateless, vulnerable people are bartered away in the name of diplomatic convenience.

But this is not inevitable. A principled international response, driven by governments that respect human rights and are willing to fund and pressure institutions to act, is still possible.