Denial of Rights: Free Trade Zones, Kashgar, and Spaces of Exception

December 10, 2024

A UHRP Insights column by Dr. Henryk Szadziewski, Director of Research, Uyghur Human Rights Project

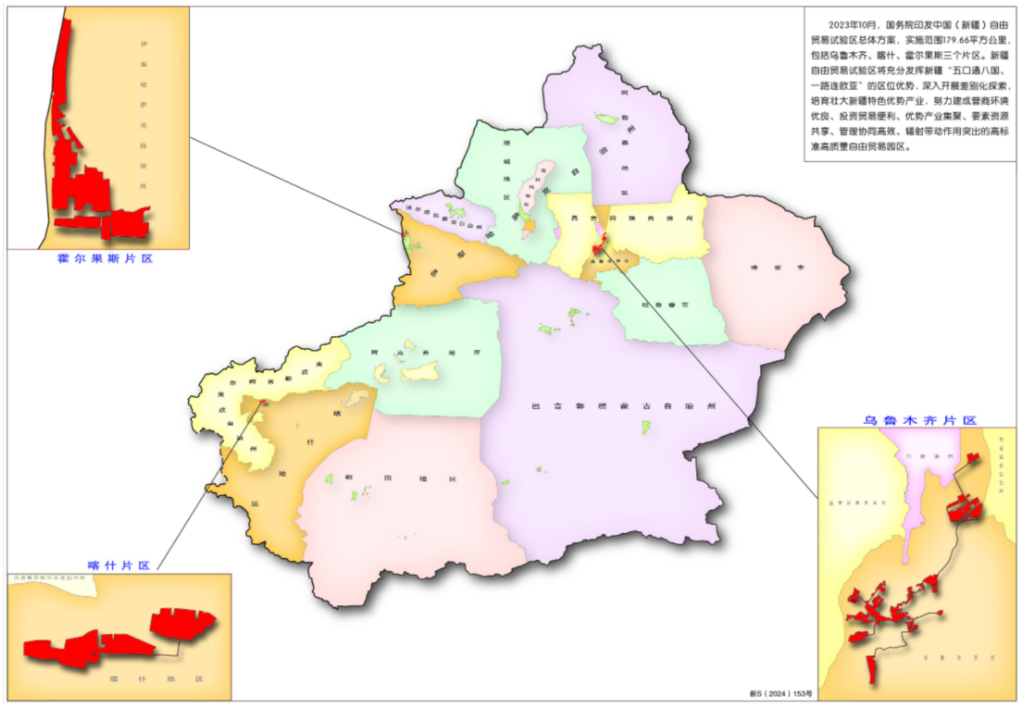

Just over a year ago, China’s State Council, the nation’s chief administrative authority, issued a plan to create the Xinjiang Pilot Free Trade Zone (FTZ). At a November 2023 inauguration ceremony in Ürümchi, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Chairperson, Erkin Tuniyaz, issued licenses for the three FTZ spaces in Kashgar, Khorgas, and Ürümchi. At the event, the regional Chairperson said the region will leverage its “resources, geographical advantages, and industrial foundation to advance the construction of the FTZ.”

Erkin Tuniyaz’s reference to geographical advantages most likely refers to the Uyghur Region’s physical location on the Eurasian landmass, offering a connection to markets across Asia and Europe. However, carving out FTZs is also an established device of political geography that has real world outcomes; one that not only further fragments once unified spaces, but also subjects newly established “zones” to different rules than the spaces around them.

Land fragmentation, through FTZs and other governance arrangements, opens opportunities for China to further territorialize and exploit the Uyghur Region, in the process denying rights to its residents. A process that is in evidence in the city of Kashgar in the region’s southwest and Ghulja/Ili in the North.

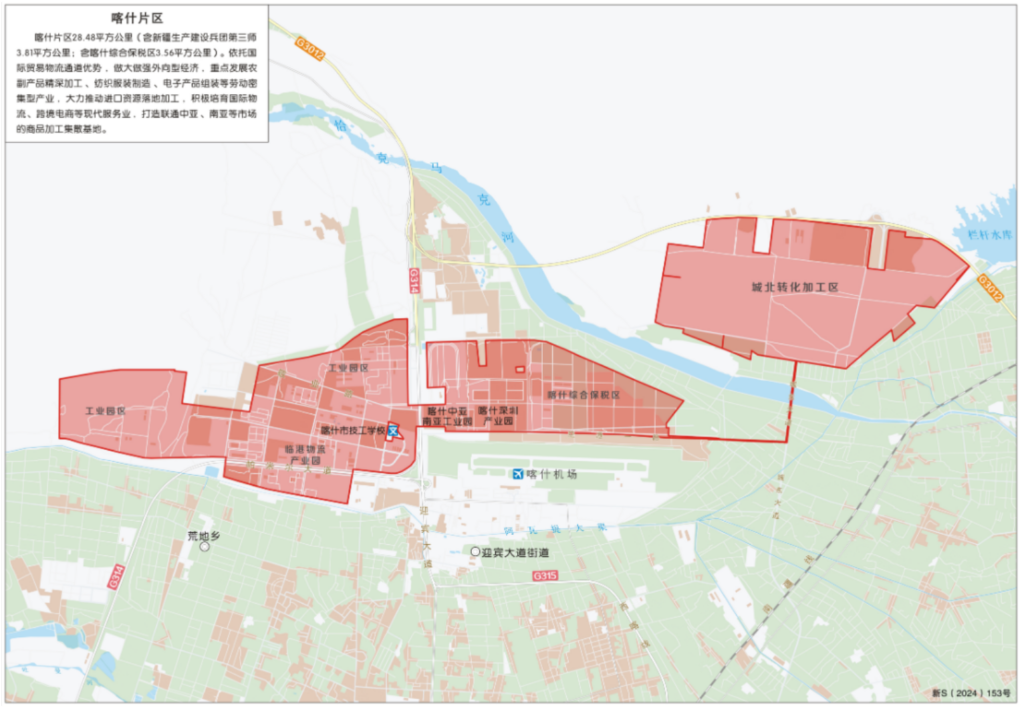

On paper, the Xinjiang Pilot Free Trade Zone (新疆自由贸易试验区) covers 180 square kilometers of Kashgar, Khorgas, and Ürümchi. Kashgar sub zone comprises 28.5 square kilometers, including territory of the Third Division of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC) and the Kashgar Comprehensive Bonded Zone (喀什综合保税区), established in 2014. The aim is to bring the pilot scheme into official status in five years, joining others, such as the Shanghai, Tianjin, and Guangdong FTZs.

A Free Trade Zone is a designated enclave, usually attached to a city or port, where goods are imported, stored, manufactured, and re-exported without incurring customs duties. The idea is to incentivize and stimulate economic activity. The overall focus of the Uyghur Region FTZ is on trade, exports, e-commerce, logistics, and “labor intensive” manufacturing. Kashgar is earmarked for the manufacture of agricultural products, garments, and electronic components for export to markets in Central and South Asia. In January 2024, China Daily reported that 86 companies had registered with the Kashgar FTZ, including Xinjiang Changxin Electronic Technology (新疆长新电子科技有限公司) and the Hualing Group (华凌集团).

Over the last several decades, the central government has made several attempts at a significant intervention in the Uyghur Region’s economy. Policies such as Open up the Northwest in the 1990s and Western Development in the 2000s, notwithstanding the globally facing Belt and Road Initiative of the 2010s, have all attempted to bring the export-driven manufacturing economy to the Uyghur Region. However, these policies have not redrawn the map of the region. This is not to say that China hasn’t already created economic enclaves in cities such as Kashgar. In May 2010, 50 square kilometers of Kashgar and the border crossing of Erkech-Tam was designated a special economic zone (SEZ) (喀什经济特区) and partnered with Shenzhen. To attract investment and new residents, the central government offered tax breaks, investment incentives, and relaxed regulations for starting businesses.

The rearrangements of Kashgar, a center of Uyghur identity and resistance, have political as well as economic purposes. Anthropologist Aihwa Ong writes how states re-territorialize spaces to enforce new forms of power that differentiate individual rights. Reconfigured economic spaces are held up as the prime example of how this differentiation operates. Unskilled workers in free trade or special economic zones, especially in the manufacturing sector, are most vulnerable to the denial of their rights in the push to offer the best conditions to attract capital. In these “spaces of exception” workers are subjected to the combined forces of global capital and state power.

The Kashgar subzone of the Xinjiang Pilot FTZ represents another “space of exception,” where the conditions of labor should come under scrutiny. Given the involvement of the Third Division of the XPCC, coerced labor in the supply chain running through the FTZ is likely. The XPCC is under sanction by the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the European Union for its systematic human rights violations. The garments and electronic components sectors, priority areas for the Kashgar subzone, are linked to forced labor.

Other economically-inspired arrangements in the Uyghur Region, such as Economic and Technological Development Zones, are spaces open to the forced labor of Uyghurs. The Xinjiang Zhundong Economic and Technological Development Zone (准东经济技术开发区) includes Xinjiang East Hope Nonferrous Metals (新疆东方希望有色金属有限公司), which the US sanctioned in 2021. Shihezi Economic and Technological Development Zone (石河子经济技术开发区) is the location of Tianshan Aluminum (天山铝业), which is at high risk of using forced labor through labor transfers. Also in Shihezi is Xinjiang Hoshine Silicon Industry (新疆西部合盛硅业有限公司), an entity implicated in forced labor practices in a 2021 report. Furthermore, the Korla Economic and Technological Development Zone (库尔勒经济技术开发区) hosts Xinjiang Zhongtai Chemical (新疆中泰化学股份有限公司) and Xinjiang Zhongtai Group ( 新疆中泰集团有限责任公司), both are on the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) Entity List.

While crimes against humanity targeting Uyghurs make the Uyghur Region a “no rights zone,” it is the noxious combination of unfettered power and capital in FTZs and development zones that creates a situation of great concern.

Kashgaris have witnessed multiple rearrangements of their city over the past 75 years of Chinese Communist Party administration in addition to new economic reconfigurations of space. The demolition and reconstruction of the old city into a tourist experience, the cartographic manipulation of prefectures into “autonomous” counties, and the carving out of territory for the centrally administered XPCC all represent means of state control and denial of rights for Uyghurs. However, in her theorizing about spaces of exception, Aihwa Ong adds that in understanding the relationship between rights and territory, activists have opportunities to advocate for people vulnerable to the power of the state and capital. As China looks to vary its strategies of repression, we hold the responsibility to remain vigilant in our documentation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Research on Economic and Technological Development Zones provided by UHRP Associate Director for Research and Advocacy, Peter Irwin. Additional material supplied by UHRP Chinese Outreach Coordinator, Zubayra Shamseden. This article was peer-reviewed by Caroline Dale of Global Rights Compliance.

NOTE

Read UHRP’s work on forced labor.