A Uyghur Human Rights Project report by William Drexel. Read our press statement on the report here, and download the full report here.

I. Key Takeaways

- Due to its unique earthen construction and lengthy history as the “cradle of Uyghur culture”, the city of Kashgar holds a profound degree of significance for the Uyghurs that is difficult to fully appreciate by outsiders. For this reason, the Chinese state has gone to extraordinary lengths to co-opt the city’s symbolic heritage.

- In Kashgar, the current campaigns of forced labor and re-education camps build upon longer histories of forced reconstruction, economic exploitation, and surveillance that have been systematically reshaping the city since the early 2000s.

- Kashgar’s reconstruction, exploitation, and surveillance have been mutually reinforcing and highly sophisticated, producing a new breed of totalitarian “smart city” optimized for ethnic repression. By staging this unprecedented urban experiment in the heart of Uyghur culture, the Chinese state has been able to coercively reinforce a living vision of Uyghur society in the service of cultural genocide.

- Kashgar can act as a prism through which to better understand a holistic picture of the Uyghur’s contemporary domination. It also stands as a disturbing portent of the new possibilities for state repression that are emerging. While Kashgar’s model of devastation currently remains unique, the tools and methods that have contributed to its condition are readily available and continue to advance.

II. Introduction

Today, it is difficult to say whether Kashgar is more remarkable for its extraordinary historical heritage, or its bizarre dystopian coercion. On one hand, the city is the “cradle of Uyghur culture”; the ancient, remote Silk Road oasis at the nexus of South Asia, China, and the Middle East; and the celebrated meeting point of Buddhist, Islamic, and Turkic influences in Central Asia. On the other hand, Kashgar has been at the front lines of the most aggressive, high-tech surveillance campaign of the 21st century; the target of a vast and totalizing anti-historical “modernizing” reconstruction project; and the new ‘special economic zone’ subjected to a state-induced process of a rapid commercialization of fantastic, destabilizing proportions. The city merits tomes on its remarkable history and on its unprecedented model of oppression. The conjunction of these two realities is, of course, no coincidence: the recent history of Kashgar is an attempt to hijack the city’s exceptional, priceless cultural heritage for exceptional, lucrative assimilation and control.

Accordingly, the study of modern Kashgar holds great significance for a variety of stakeholders, particularly at this juncture of immense repression and change. To historians, anthropologists, area studies scholars, and architects, the irreversible destruction of the city is a tragedy worthy of as much documentation, exploration, and knowledge-preservation as possible. To technologists, ethicists, activists, and students of political science, the novel modes of oppression pioneered in Kashgar at truly unprecedented speeds represent a window into what is possible through new technological modes of domination, as well as the ambitions and methods of the Chinese state to accomplish its aims.

Here is a storied, 2–3 millennia-old city of precious value for the transmission, confluence, and development of great, ancient traditions—razed, reconstructed, exploited, and surveilled with uncanny speed and unprecedented power.

Perhaps most importantly, though, the recent story of Kashgar is one of general relevance for anyone interested in the development of human culture and civilization broadly: here is a storied, 2–3 millennia-old city1Global Heritage Network, “Site Conservation Assessment (SCA) Report, Kashgar Old City, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region,” January 1, 2010, 3, ghn.globalheritagefund.com/uploads/documents/document_1950.pdf of precious value for the transmission, confluence, and development of great, ancient traditions—razed, reconstructed, exploited, and surveilled with uncanny speed and unprecedented power, often through technological processes only recently made possible. Here is the cultural nucleus of a people that has been dramatically re-architected amid a broader campaign of systematic cultural genocide.2For more on the use of “cultural genocide” terminology see Adrian Zenz, “The Karakax List: Dissecting the Anatomy of Beijing’s Internment Drive in Xinjiang,” Journal of Political Risk 8, no. 2 (February 2020), https://www.jpolrisk.com/karakax. As related, “the Karakax List lays bare the ideological and administrative micromechanics of a system of targeted cultural genocide that arguably rivals any similar attempt in the history of humanity.” Kashgar is a cautionary tale, a human tragedy, and an ongoing cause as the Uyghur people continue to fight for their existence. The city’s story exhibits the new limits of oppression that contemporary technological advancements, in combination with a technocratic party-state, make possible.

Kashgar as a city has become a coercive agent in its own right, as mechanisms of surveillance and urban planning enmeshed in the new city-scape force its inhabitants into behaviors and systems that instrumentalize the city’s heritage in the service of cultural destruction and control.

With this in mind, I aim to write from a perspective of general human interest, seeking to make sense of modern Kashgar. This report aims to detail the nature and meaning of Kashgar’s recent history at this historical inflexion point, while the city’s transformation is still fresh and memories of its historic character still remain. This report also aims to capture the nature of the oppression and cooptation occurring through Kashgar’s plight, unprecedented in its unique combination of features. The study is meant to help anyone seeking to interpret the city today, whether as tourist, academic, reporter, or Uyghur. To that end, this report has two further aims. First, it seeks to center the Uyghur experience to express the tragedy of Kashgar’s recent history. Second, it suggests some conceptual language by which to better understand the unique changes in the city. Whereas various cities around the world are attempting to fashion themselves as “smart cities,” interweaving technology, urban planning, and culture towards greater efficiency, connectivity, and human flourishing, Kashgar in many ways has already been made into a pioneering “smart city” itself. However, rather than aiming towards human flourishing, Kashgar’s urban “intelligence” has been engineered to be coercive to the freedom and culture of the Uyghur people, becoming something like a “malicious city.” Thus, Kashgar’s coercion can be interpreted in two related senses. In the more obvious sense, Kashgar has been coerced by the Chinese state through its reconstruction, intense policing, mass internment, forced labor, and cultural exploitation. In the more novel sense, Kashgar as a city has become a coercive agent in its own right, as mechanisms of surveillance and urban planning enmeshed in the new city-scape force its inhabitants into behaviors and systems that instrumentalize the city’s heritage in the service of cultural destruction and control. To comprehend the novelty of what has occurred in Kashgar, a new vocabulary is necessary, along with careful reflection upon the social, economic, and technological developments that have made it possible.

III. Methodology

This report brings together recent reports on Uyghur repression and Kashgar, along with scholarship on urban planning, anthropology, political science, and history. The author has spent a year in China studying state surveillance, including a short stint in East Turkistan in the fall of 2018. During his time in Kashgar, he observed the state of the Old City and came across undocumented evidence of more recent cultural erasure in the Kozichi Yarbeshi neighborhood, as will be presented later in this report. He has conducted several informal interviews with locals in Kashgar, as well as with a variety of tourists who have intermittently visited over the course of 2019. With the assistance of UHRP, the author has conducted formal interviews with several Uyghurs from Kashgar now living abroad.

Admittedly, under ordinary circumstances, one would hope for a more comprehensive or systematic approach to interviews and on-the-ground research. Anyone familiar with the current situation in Kashgar and East Turkistan, however, understands that means of communication are highly limited and risky, even as the importance of speaking out and gathering information is considerable. The author is therefore thankful to all those he has spoken with, knowing that his interlocutors take on significant risk in speaking to him. Therefore, unless explicitly requested otherwise, the author has changed the names and identifying details of all those he has spoken with. Additionally, he writes under a pseudonym for greater protection both for himself and his sources. He speaks neither Uyghur nor Chinese, and is therefore deeply indebted to the help of Joy Liu,* a translator and native speaker of both Chinese and English, who is also working under a pseudonym for similar reasons. Without Joy’s inspiration, tireless research, and language support, this report would not be possible. All translations are her own.

This report contributes to now highly developed literatures on both the recent repression in East Turkistan and Kashgar’s reconstruction. In terms of scope, it aims only to better understand Kashgar’s recent transformation, roughly covering the period from 2000 until mid 2020. Both the broader history of the city, and the broader ecosystem of cultural erasure at work are beyond the purview of this report and will be referenced only insofar as they contribute to the understanding of contemporary Kashgar.

Accordingly, it is worth noting that many of the trends and developments discussed within this report are at work in other areas of East Turkistan, sometimes to a greater degree than in Kashgar. Turpan and Hotan have seen similar reconstruction initiatives,3 Tianyang Liu and Zhenjie Yuan, “Making a Safer Space? Rethinking Space and Securitization in the Old

Town Redevelopment Project of Kashgar, China,” Political Geography 69 (March 1, 2019): 34,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.12.001 and may have some areas of more stringent surveillance. Indeed, the Chinese government has also allowed or initiated significant uses of space and architecture as a means of social or political control in more far-flung areas, such as the case of the Three Gorges Dam or the ‘redevelopment’ of a variety of historical Chinese cities.4Liu and Yuan, 40. However, the case of Kashgar is unique for its particular cultural significance within the broader repression of the current time and its uniquely visible manifestations of state policies of economic exploitation, reconstruction, and surveillance directed at the Uyghur culture.

Of course, many of the elements that have made Kashgar what it is today were as directed by market forces as by the state. In this sense, Kashgar’s transformation has been the result of a variety of actors with a variety of interests, even if state policy has been a clear guiding force. Accordingly, different changes elicited differing ranges of responses, and a few developments were even supported by some segments of Kashgar’s Uyghur population (if generally not the prevailing opinion). Where possible, I will attempt to note those instances. Nonetheless, while a few individual changes may or may not have been welcomed by some at the time of their arrival, these multifarious developments compound and coalesce in contemporary Kashgar to generate a particular sort of domination that is unique: instructive for anyone hoping to understand the final end-product of years of Chinese ethnic policy in combination with new surveillance and “reeducation” initiatives for Uyghurs. As an embodied cityscape of immense cultural and historical significance, Kashgar can act as an important symbolic prism through which to view the cumulative effect of ethnic repression at work in East Turkistan today, at a time when assessing the full scope and significance of the Uyghur plight is particularly difficult.

IV. Historical & Ethnic Significance

In part due to the city’s unique geographic position, the historical legacy of Kashgar is vast. Trying to recount the city’s rich, multi-millennia history would be far too great a task for this paper. A brief sense of the city’s lengthy historical significance would include how Kashgar has been the seat of numerous kingdoms, the contested jewel of empires, and the home of Manichean, Buddhist, Zoroastrian, and Nestorian traditions. When Islam entered China (and the Turkic world) via Kashgar, the city was where “the early Muslims encountered strong Chinese, Persian, Turkic, and Indian influences” due to its “natural intersection of ancient pathways leading from the capitals of Rome, Persia, Mongolia and China.”5Dru Gladney, “Kashgar: China’s Western Doorway,” Saudi Aramco World, December 2001. When Marco Polo visited the city in 1272, he marveled at its grandeur and regional prominence.6Joshua Hammer, “Demolishing Kashgar’s History,” Smithsonian Magazine, March 2010, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/demolishing-kashgars-history-7324895/ Centuries of cultural transmission, trade, and religious scholarship shaped the city into an enduring cultural epicenter of Central Asia from ancient times.

Beyond its lengthy historical importance as a crossroads between empires and civilizations, for hundreds of years, the city has also been “the historical heart of Muslim Uyghur Culture…. Remain[ing] both the physical and the symbolic nucleus of traditional Uyghur society.”7Michael Dillon, Xinjiang and the Expansion of Chinese Communist Power: Kashgar in the Early Twentieth Century, 1 edition (New York: Routledge, 2014), xviii. As one ex-resident told me recently, “If you visit Turkistan and miss Kashgar, you have missed Turkistan.” Li Kai, a Han Chinese writer and scholar renowned as an authority on the region, asserts that the city is beyond comparison as the “quintessence of Uyghur culture” with the highest concentration of Uyghurs anywhere in the world and a unique cultural genius.8Li Kai, “Silu mingzhu Kashiga’er’, Kashi 1:10; quoted in Dillon, 3. The city’s status as the spiritual capital of the Uyghur people is uncontested, and has been for centuries. Kashgar is at once the heartbeat, center, and epitome of Uyghur culture.

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) inserted itself into this history and cultural significance by entering Kashgar in 1949, claiming “peaceful liberation” for its inhabitants. Since that time, the city has been under Communist rule, posing acute barriers to understanding the city’s history from 1949 to the 1980s. Admittedly, the remote positioning of the city already meant that it had long been seen as distant and mysterious to much of the outside world; nonetheless, Communist rule compounded this inaccessibility by restricting all foreign travel to the city save a “trusted few, who could be relied on to report favorably on the way Xinjiang was developing under the rule of the CCP…[who were] allowed restricted access.”9Dillon, 1. As such, clear information on how early CCP rule shaped Kashgar until the 1980s is relatively scarce.

What is known—and often overlooked in recent media reports—is the dramatic effect that the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) had on East Turkistan in general, and Kashgar in particular. Although the Cultural Revolution is often thought of as a Chinese affair, from the perspective of Uyghurs in East Turkistan the event ostensibly arrived as a manifestation of severe Han Chinese repression of conquered, occupied lands. Predominantly Han Red Guards invaded East Turkistan on a mission to destroy the “Four Olds:” Old Customs, Old Culture, Old Habits, and Old Ideas. In the case of ethnic minorities like the Uyghurs, this meant a concerted, Han-led campaign of sustained ethnic cultural persecution, including the mass burning of books and widespread destruction of cultural artifacts. At the beginning of the campaign, Kashgar was home to 107 mosques; by its end, only two remained open.10Gardner Bovingdon, The Uyghurs: Strangers in Their Own Land (Columbia University Press, 2010), 65–66. Men were forcibly shaved in the streets, Muslims were made to raise pigs, and Uyghurs were made to exchange their traditional clothes and adornments for Mao suits. Cultural humiliation was severe, and societal damage was crippling as intellectuals and community leaders were imprisoned and tortured.11Bovingdon, 51–52.

Prior to the 2000s, the Cultural Revolution certainly represented the most severe, though not the only,12Darren Byler, “Ghost World,” Logic Magazine, May 1, 2019, https://logicmag.io/china/ghost-world/ era of Chinese ethnic repression against the Uyghurs since Communist seizure of power. I highlight the event for two reasons: first, to note that some of what has been going on in the city has significant antecedents in history that are underreported and set the stage for Kashgar’s later repression. Second, and more relevant for our purposes, the Cultural Revolution had a lasting impact on Kashgar itself. For one, the Cultural Revolution altered the architecture of Kashgar’s Old City: in the 1970s, Old City residents “created an even more complex subterranean ‘city’ beneath the already maze-like surface of the old town” to escape attacks during the Cultural Revolution.13Liu and Yuan, “Making a Safer Space?,” 34. Furthermore, with such comprehensive destruction of precious cultural books, manuscripts, artifacts, and art over the course of the Cultural Revolution, the embodied, material culture of Kashgar’s Old City took on heightened cultural significance to the Uyghurs. Their writings and artefacts may have been destroyed, but their ancient city and its distinctive way of life remained as the preeminent bastion of the Uyghur way of life and an enduring symbol of cultural achievement.

This is not to suggest by any means that Kashgar’s contemporary significance is merely reactionary to the cultural erasure of the Cultural Revolution—the latter merely augmented Kashgar’s pre-existent cultural preeminence. Indeed, to an outside observer, it is difficult to fully grasp the extent or nature of Kashgar’s significance to the Uyghur people, which differs significantly from the cultural appreciation that most ethnic groups might have towards their important urban centers. To understand the coercive power of Kashgar, however, understanding the unique relationship between Uyghurs and Kashgar is essential.

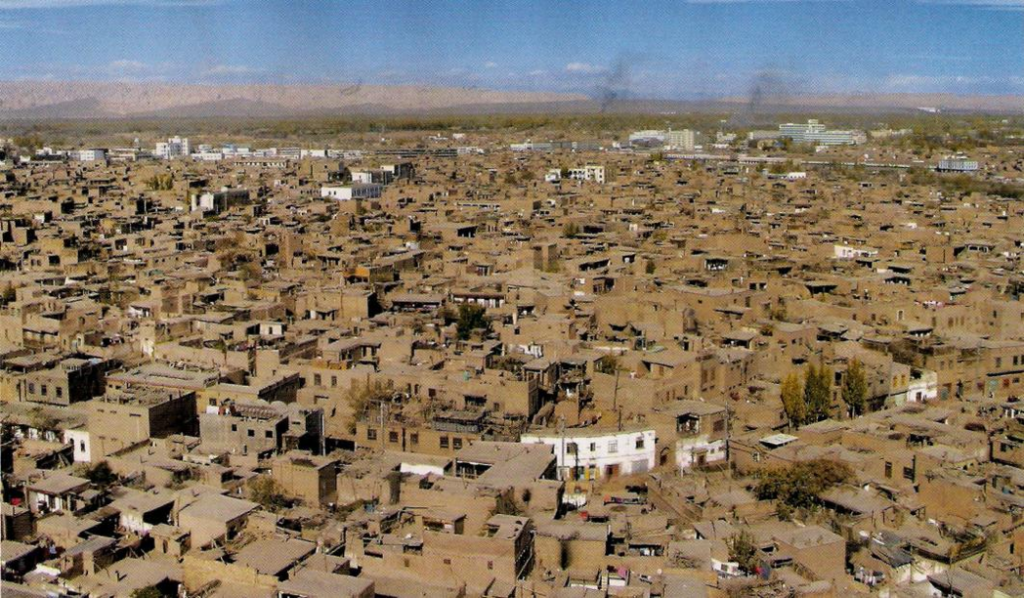

The first step in appreciating the cultural import of Kashgar is to attempt to understand just how unique and idiosyncratic its architectural-communal style was prior to reconstruction. The “grandeur” of Kashgar was not, as in the case of many analogues, merely a matter of the city’s architectural wealth or the grandness of its more illustrious buildings. Instead, Kashgar’s centuries-long, interwoven, fractal mud-brick evolution developed a truly remarkable socio-architectural web that is difficult to fully communicate to anyone who has not experienced its unique atmosphere. In the same way that Venice’s unusual water-entwined cityscape intuitively fascinates its visitors with its rare, aqueous structure, so also might Kashgar fascinate the visitor with its highly unusual, multi-layered, and intertwined earthen structure. Both the organic building materials and the intricately entangled structures throughout the Old City created a unique, communal burrow-like aesthetic: like a gigantic clay hive bulging out of the earth, acting as the substratum for a highly unique style of communal-religio-cultural life for tens of thousands over the course of centuries.

It is difficult to fully grasp the extent or nature of Kashgar’s significance to the Uyghur people, which differs significantly from the cultural appreciation that most ethnic groups might have towards their important urban centers.

Liu and Yuan’s “volumetric” approach to understanding the Old City does well to describe how the interwoven architecture of the traditional Uyghur aywan construction style operates in Kashgar, from the bottom up:

“A complex tunnel system (with an estimated total length of 36 km) . . . was built individually, secretly, and often combined with the basement structure of the aywan-style houses . . . connect[ing] the homes of related families living in close proximity. This has created an even more complex subterranean ‘city’ beneath the already mazelike surface of the old town. Though unorganized in form and hybrid in their functions, these vertical extensions represent the spontaneous, locally determined practices of lived space . . . . . . [On the surface level] the irregular distribution and the continuous bends in the walls of the aywan house supply the neighborhood with myriad entrance and exit points, visual blind-spots and dead-end streets…It also transforms the neighborhood into a territorial ecosystem of internally-oriented (but externally-alienated) enclaves which, by and large, can only be flexibly accessed and fully utilized by the insiders (i.e. local Uyghur residents). Thus, with its three-dimensional matrix of houses, streets and tunnels, the multi-story structure of the old town provides connectivity between different dwellings and adjoining streets, making the neighborhood an internally-interconnected space. . . . [B]ridge-houses constructed above the ground [on top of pre-existent dwellings] . . . are built by local families to cope with the lack of residential spaces for fast growing families in the old town . . . [expanding] rooftop connectivity…These bridges transform the old town into a monolithic network and, like blood vessels, support the centuries-old social ecology of the old town. The hundreds of officially unregistered and irregular bridgehouses provide a vertical solution to the problem of overcrowded dwellings, but simultaneously create (and complicate) the unique vertical spaces of the old town.”14Liu and Yuan, 34.

Reflective of this unique construction style and history, a typical observer would be immediately struck by the way Kashgar’s Old City evokes complex, visually impressive webs of interconnected communal life. For Uyghurs, the city at once instantiated and protected their inimitable communal tradition.

Moving beyond the complexity and interwoven-ness of the Old City as a whole, we can consider the construction features of the houses themselves, dense with social meaning and cultural praxis. We first consider the locations of the houses in proximity to the city’s mosques. As Liu and Yuan have plotted, the Old City was speckled by 112 fairly evenly dispersed mosques, each of which would serve 10–25 households within a radius of 50–100 meters,15Liu and Yuan, 34. creating an ecosystem of embedded religious practice within the community.

The center of the traditional Kashgari home was the courtyard, around which orbited the family’s culinary, religious, and leisurely practices—integrating not only Islamic influences, but also many traditions, symbols, and practices that harken back to Uyghurs’ prior Buddhist, Manichean, and Nestorian pasts. Old City homes were adorned with traditional Uyghur decorative art, woodwork, and pottery, and were often centuries old. Kashgaris were often extremely proud of their homes’ layered history and architectures, and the ways in which their ancestors benefitted from and lived into the intense architectural interconnectedness that they, until recently, also inhabited. Interviewees spoke with pride and warmth about the way that navigating Kashgar’s old, narrow, labyrinthine alleyways was a challenge both directionally and physically, as one had to fight their way through crowded streets amid the sights, sounds, and smells of various shopkeepers and bakers packed into the city’s tight, winding corridors.

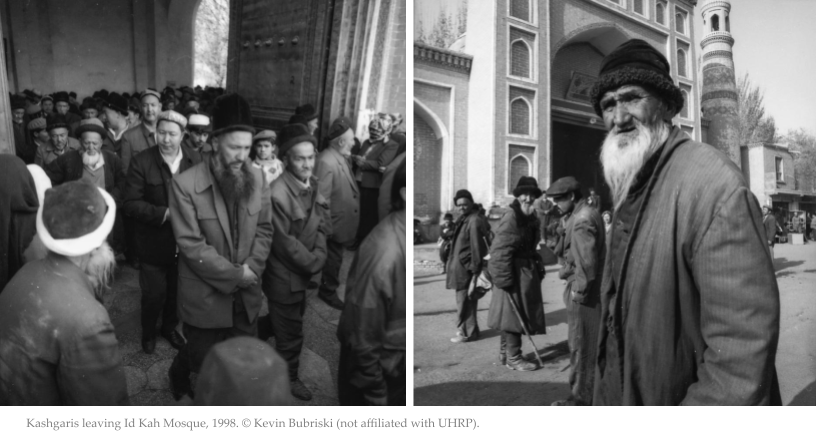

More than just a unique urban mass, however, Kashgar also maintained rich societal traditions built into its topography. At the end of Ramadan and Qurban Eid, for instance, thousands would gather in front of the Old City’s Id Kah Mosque—the largest in East Turkistan (and all of China)—to pray. After prayers, Uyghur musicians would climb to the top of the mosque and play traditional music as the crowds broke into the iconic Sama dancing for which the Uyghurs are famous. The rhythms, movement, and majestic Id Kah backdrop are inscribed in the minds of many Uyghurs as the quintessential image of Uyghur cultural brilliance. Also worth noting is the remarkable level of selfsufficiency achieved by Kashgar’s Old City. As Michael Dillon notes, “As a whole, these buildings and institutions [of the Old City] cater to virtually every need of the local Uyghur community. . . . Their selfsufficiency and self-reliance enable the Uyghurs [of Kashgar] to limit the contact that they have with the Han-dominated local government and afford them a degree of de facto autonomy.”16Michael Dillon, “Religion, Repression, and Traditional Uyghur Culture in Southern Xinjiang: Kashgar and Khotan,” Central Asian Affairs 2, no. 3 (May 29, 2015): 253, https://doi.org/10.1163/22142290-00203002 While this autonomy would be viewed with concern by Chinese authorities, the advantages for the Uyghurs of Kashgar and beyond are obvious: beyond housing, facilitating, and preserving Uyghur culture, the collective social, religious, and economic institutions of Kashgar’s Old City allowed for a degree of relative insulation from the Chinese state, and, by extension, a place of hope for the freedom and cultural self-determination of the Uyghur people as a whole.

The collective social, religious, and economic institutions of Kashgar’s Old City allowed for a degree of relative insulation from the Chinese state, and, by extension, a place of hope for the freedom and cultural selfdetermination of the Uyghur people as a whole.

Thus, the holistic cultural significance of Kashgar can come into clearer focus. Architecturally, the construction of the city was remarkable, historical, beautiful, and unique for its earthen construction and complex interwoven structure. Historian George Mitchell accordingly called Kashgar “the best preserved example of a traditional Islamic city to be found anywhere in Central Asia.”17Claire Alix, “Statement of Concern and Appeal for International Cooperation to Save Ancient Kashgar,”

SAFE/Saving Antiquities for Everyone (blog), July 20, 2009, http://savingantiquities.org/statement-of-concernand-appeal-for-international-cooperation-to-save-ancient-kashgar/ Indeed, “many experts viewed Kashgar as one of the greatest examples of mudbrick settlement anywhere in the world.”18Nick Holdstock, China’s Forgotten People: Xinjiang, Terror and the Chinese State, 1 edition (I.B. Tauris, 2019), chap. 7 For Hollywood director Marc Forster, Kashgar’s beauty and Central Asian authenticity made it the natural site selection for his 2007 adaptation of The Kite Runner to represent 1970s Afghanistan.19Hammer, “Demolishing Kashgar’s History.” When that architecture came under threat in the late 2000s, a host of international organizations voiced their grave concern at the potential loss of priceless architectural heritage, including (but not limited to) Saving Antiquities for Everyone (SAFE), Global Heritage Network (GHN),20Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Living on the Margins: The Chinese State’s Demolition of Uyghur Communities” (UHRP, April 2, 2012), 58, https://uhrp.org/press-release/new-report-uhrp-living-marginschinese-state%E2%80%99s-demolition-uyghur-communities.html the European Parliament,21Uyghur Human Rights Project, 61. UNESCO,22Uyghur Human Rights Project, 22–23. and the International Scientific Committee on Earthen Architectural Heritage, which claimed that Kashgar’s Old City was of “unquestionable Universal Value” as one of the largest groupings of mud-brick architecture in Central Asia, and, likely, the world.23Zeynep Aygen, International Heritage and Historic Building Conservation: Saving the World’s Past (Routledge, 2013), 79. In this sense, Kashgar’s significance stretches beyond that of a typical historical city, for it represents not just the legacy of the events that took place within its (now destroyed) walls, but the archetype of a rare form of urban creation, something akin to what Westerners might ascribe to Venice as a “floating city,” for example.

More importantly, however, Kashgar’s significance is found in how its unusual cityscape was uniquely refined over centuries to support an extraordinarily integrated community life of Uyghur cultural practice and tradition. As families revolved around their interconnected courtyards, so also ancient neighborhoods revolved around their centuries-old mosques, and the collective imagination of the Uyghur people revolved around the communal life of Kashgar. Not only did the great poets, prophets, and kings of the Uyghur people make their home in Kashgar, the immersive structure of the city also created a living order of robust Uyghur cultural expression, insulated from the state.

To fully explain the significance of Kashgar, then, the words of famed public intellectual Lewis Mumford come to mind:

“The city in its complete sense, then, is a geographic plexus, an economic organization, an institutional process, a theater of social action, and an aesthetic symbol of collective unity. The city fosters art and is art; the city creates the theater and is the theater. It is in the city, the city as theater, that man’s more purposive activities are focused, and work out, through conflicting and cooperating personalities, events, groups, into more significant culminations. . . . The physical organization of the city may deflate this drama or make it frustrate; or it may, through the deliberate efforts of art, politics, and education, make the drama more richly significant, as a stage-set, well-designed, intensifies and underlines the gestures of the actors and the action of the play.”24Lewis Mumford, “What Is a City,” Architectural Record, 1937, http://jeremiahcommunity.ca/wpcontent/uploads/2019/01/Mumford-What-is-a-City.pdf

In Mumford’s terms, Kashgar has long since ceased to be the most important “stage-set” of the Uyghur drama. To a degree exceedingly rare in cultures across the world, Kashgar has merged with that drama—has become a central element of the drama, the “art” of being Uyghur. That is why for many Uyghurs the city has even taken on significance that is quasi-religious. As one report by the Uyghur Human Rights Project notes, Kashgar “is viewed by Uyghurs as Jerusalem is to Christians, Jews, and Muslims.”25 Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Living on the Margins: The Chinese State’s Demolition of Uyghur Communities,” 33. As the historical center—and an immersive instantiation—of Uyghur culture, Old Kashgar commanded a respect and reverence difficult to comprehend by outsiders, and, as we shall see, coveted by the Chinese state.

One statement from a native of the Kashgar region particularly drives the point home:

“When the reconstruction really started happening, it was felt by all Uyghurs. At that time, I was far away, in Ürümqi, but it made no difference, we all felt it. Even the little Uyghur children knew. They knew that something was wrong. . . . When I came back to my home area after the demolitions for the first time in [many] years, I traveled to the Old City. I saw it from a distance—the outside—and I simply could not bring myself to enter in. I don’t know why. I have not been back since.”26Mujahit* Hassan*, Recollections of Kashgar, February 18, 2020.

V. Reconstruction

The reconstruction of Kashgar has been an iterative, piecemeal process, the motivations of which are often opaque, overlapping, and impossible to delineate with certainty as the process has unfolded. A good deal of prior research has examined the intentions that went into numerous stages of Kashgar’s reconstruction. The most comprehensive study of these questions that this researcher has found comes from UHRP’s 2012 report Living on the Margins,27Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Living on the Margins: The Chinese State’s Demolition of Uyghur Communities.” which synthesizes preservation attempts from various international organizations, reporting from residents, the economic feasibility of preserving the Old City, and Chinese manipulation of UNESCO authority to justify its actions. Generally, accounts have variously focused on:

(1) Chinese state concern over the relative autonomy of Kashgar,28Dillon, “Religion, Repression, and Traditional Uyghur Culture in Southern Xinjiang,” 253.

(2) real or perceived fear of Old City architecture as conducive for terrorist activity,29Liu and Yuan, “Making a Safer Space?,” 32.

(3) a general assertion of Chinese state power,30R. Spencer, “Fibre of Silk Road City Is Ripped Apart,” The Telegraph, July 16, 2005.

(4) an attempt at long-term (forced) ethnic assimilation,31Liu and Yuan, “Making a Safer Space?,” 32.

(5) weakening of Uyghur culture, religion, tradition, and/or family life,32Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Living on the Margins: The Chinese State’s Demolition of Uyghur

Communities.”

(6) working towards earthquake resiliency/risk mitigation (official government stance for much of the reconstruction),33Uyghur Human Rights Project, 37.

(7) reprisal for Uyghur-Han ethnic violence,34Holdstock, China’s Forgotten People, chap. 7.

(8) dilution of densely Uyghur-populated areas,35Spencer, “Fibre of Silk Road City Is Ripped Apart.”

(9) a governmental drive towards economic development,36Amy H. Liu and Kevin Peters, “The Hanification of Xinjiang, China: The Economic Effects of the Great Leap West,” Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 17, no. 2 (2017): 267, https://doi.org/10.1111/sena.12233 and

(10) commercial interests.37Holdstock, China’s Forgotten People, chap. 7.

These motivations and interests are interlocking and likely contain various degrees of truth at each juncture of decision-making over what has been a lengthy process.

Today, in light of China’s expansive, mass campaign of mosque, shrine, and grave demolition now occurring across all of East Turkistan, the longer process of Kashgar’s reconstruction retroactively appears more nefarious as a portent of things to come. Expert Bahram Sintash estimates that 10,000 to 15,000 religious sites have been destroyed across East Turkistan since 2016,38Fred Hiatt, “In China, Every Day Is Kristallnacht,” Washington Post, November 3, 2019, sec. Opinions, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2019/11/03/china-every-day-is-kristallnacht/ drawing upon his own research in collaboration with that of RFA, Bellingcat, the Guardian, and AFP.39Bahram Sintash, “Demolishing Faith: The Destruction and Desecration of Uyghur Mosques and Shrines | Uyghur Human Rights Project,” October 28, 2019, https://uhrp.org/press-release/demolishing-faithdestruction-and-desecration-uyghur-mosques-and-shrines.html While these events do not bode well for Kashgar’s reconstruction projects prior to 2016, that year was very clearly a turning point, due to the installation of Chen Quanguo as the Party Secretary over East Turkistan in August. Thus, the reconstruction projects forced upon Kashgar prior to 2016 were very likely distinct in many ways from the plans that characterize the current era of oppression. That said, there can be no doubt that the cascade of government policies that have reshaped Kashgar since 2000 share with the post-2016 measures common threads of governmental subjugation, disregard for—and cooptation of—Uyghur culture, and severe ethnic suppression.

Rather than walking through the motives and controversies that surrounded each stage of Kashgar’s reconstruction, a task that (at least in the early stages) has been well-documented elsewhere,40Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Living on the Margins: The Chinese State’s Demolition of Uyghur Communities.” I will only briefly recount the major developments that have occurred in chronological order, with some notes on their significance, to illustrate the material evolution of Kashgar. Beginning around 2000, I will relay the major stages of Kashgar up to 2016, at which point the city’s reconstruction became inseparable from the broader program of East Turkistan’s reconstruction now in full steam. I will then consider Kashgar’s reconstruction within that broader context, until the present day in which new areas remain under threat.

Again, it is worth noting that some significant alterations had occurred before 2001. For example, most of the gargantuan, earthen city wall was slowly destroyed prior to the turn of the century, and a paved main street was made to shoot through the Old City.41Holdstock, China’s Forgotten People, chap. 7. In the 1980s, the moat that surrounded the city was also filled in to create a ring road around the Old City.42Michael Wines, “To Protect an Ancient City, China Moves to Raze It,” The New York Times, May 27, 2009, sec. World, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/28/world/asia/28kashgar.html Around 2000, however, a series of campaigns— each more dramatic than the last—began to take shape that would irreparably alter the heart of the city.

Early 2000s: The Clearing of Id Kah Square & Early Reconstruction Under the Great Western Development Program

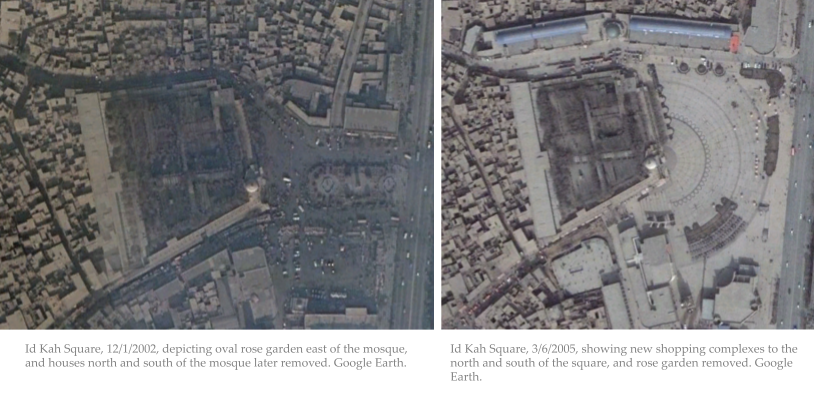

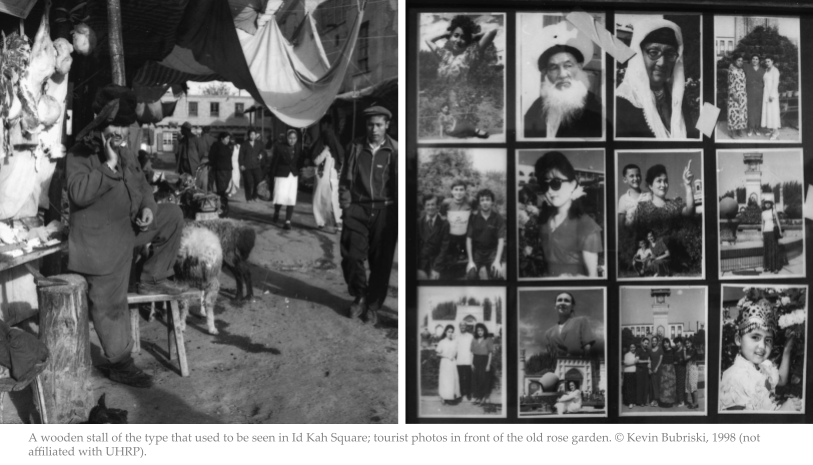

The recent succession of aggressive policies towards Kashgar began with the 1999 announcement of the Great Western Development Program by the Chinese central government, in which the government sought to focus on the development of its western reaches after two decades of coastal development.43Hongyi Lai, “China’s Western Development Program: Its Rationale, Implementation, and Prospects on JSTOR,” Modern China 28, no. 4 (n.d.): 432–66. It was under the auspices of this program that the first recent reconstructions of the Old City were enacted, most notably the clearing of Id Kah Square around 2000–2001. The mud-brick bazaar in front of Id Kah mosque had been a center of Kashgar community life, with scores of family shops abutting the market, living quarters adjoined. Abruptly, shops, families, and houses were cleared to make way for a more open, “modern” square,44Christian Tyler, Wild West China: The Taming of Xinjiang, First Edition edition (New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, 2004), 218. upending untold years of familial and societal tradition. Demolished family-owned shops and houses tended to be replaced by more commercialized shops, and a gigantic, concrete platform. Unfortunately, Google Earth’s satellite imagery only stretches back as far as 2002, meaning that satellite evidence of much of the initial market clearing does not exist. However, satellite images do recount the subsequent destruction and removal of the iconic rose garden once tightly associated with Id Kah Mosque, and some surrounding homes removed on the north side of the square, replaced by commercialized shops.

It was around this same time that the famed, centuries-old Sunday bazaar was moved out of the city walls and wooden stalls into an ordered, “rectangular concrete expanse under a stainless–steel canopy.”45Spencer, “Fibre of Silk Road City Is Ripped Apart.” The accompanying animal market was moved out of the city altogether. Uproar at the hundreds of displaced families, destroyed market, and unilaterally transformed Id Kah square was widespread.46Spencer.

2009–2014: Mass Reconstruction, the “Kashgar Dangerous House Reform” Program, and Beyond

While various reconstructions and displacements continued after the clearing of Id Kah Square, Kashgar’s reconstruction significantly accelerated in 2009, when the government announced a large-scale project to demolish and rebuild 85% of the Old City under the “Kashgar Dangerous House Reform” program.47Hammer, “Demolishing Kashgar’s History.” According to the Congressional Executive Committee on China, the plan aimed at resettling nearly half of Kashgar’s overall population (Old City together with outside areas) with a budget of USD$439 million.48Congressional-Executive Commission on China, “Demolition of Kashgar’s Old City Draws Concerns Over Cultural Heritage Protection, Population Resettlement,” April 7, 2009, https://www.cecc.gov/publications/commission-analysis/demolition-of-kashgars-old-city-draws-concernsover-cultural Despite international outrage and concerted efforts to advocate for preservation (rather than demolition and reconstruction) the plan went ahead at speed. In the summer of 2009, Kashgar officials unveiled a plan to relocate and reconstruct the homes of 65,000 households accounting for more than 200,000 people.49Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Living on the Margins: The Chinese State’s Demolition of Uyghur Communities,” 34. Expanded government proposals were announced in 2010 and 2011, suggesting expanded demolitions of tens of thousands of households.50Uyghur Human Rights Project, 35–36.

The early stages of this reconstruction process were well documented by photographer Stephen Geens, who mapped the reconstructions through November 17, 2011. He notes that by that time, around two thirds of the Old City had been demolished, with the 85% goal seemingly persisting. He also recounts how the demolitionreconstruction process is often completed with such speed that satellite images do not easily show that a reconstruction has occurred at all due to the gap of time between aerial snapshots. 51Stefan Geens, “The Last Days of Old Kashgar — an Update,” Ogle Earth (blog), February 24, 2012, https://ogleearth.com/2012/02/the-last-days-of-old-kashgar-an-update/

Geens’s work has been extremely helpful in showing how reconstruction progressed over time. However, much of the reconstruction occurred after his documentation ended, further enveloping the city in more new architecture. Although much of said reconstruction would be imperceptible from satellite photos, some indicative shots do shed some light on the transformations after 2011. Take, for instance, the following photos of an area un-documented by Geens. Although many more of the buildings than are depicted here likely had already been—or soon would be—destroyed, the image captures something of how reconstruction was evolving:

Notice also that even one of the two areas listed as “protected” in 2011 experienced significant reconstruction in 2012—again, likely including much more than is clearly depicted by the satellite data:

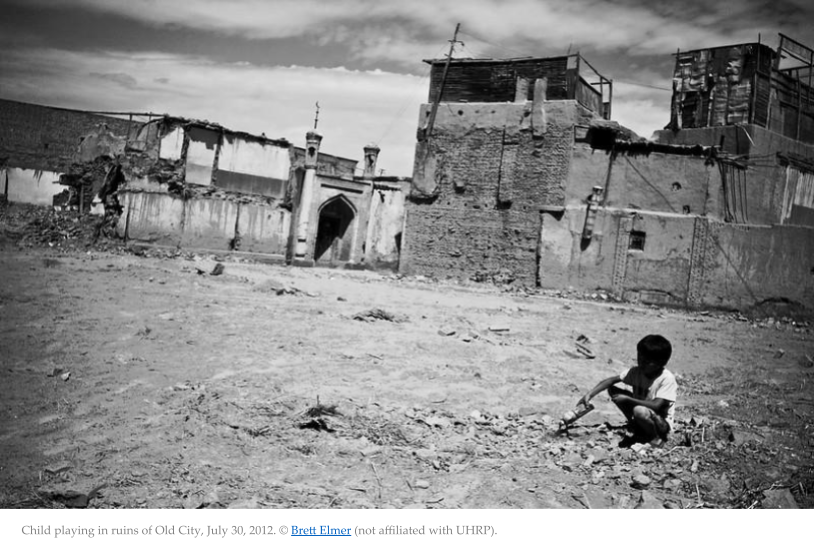

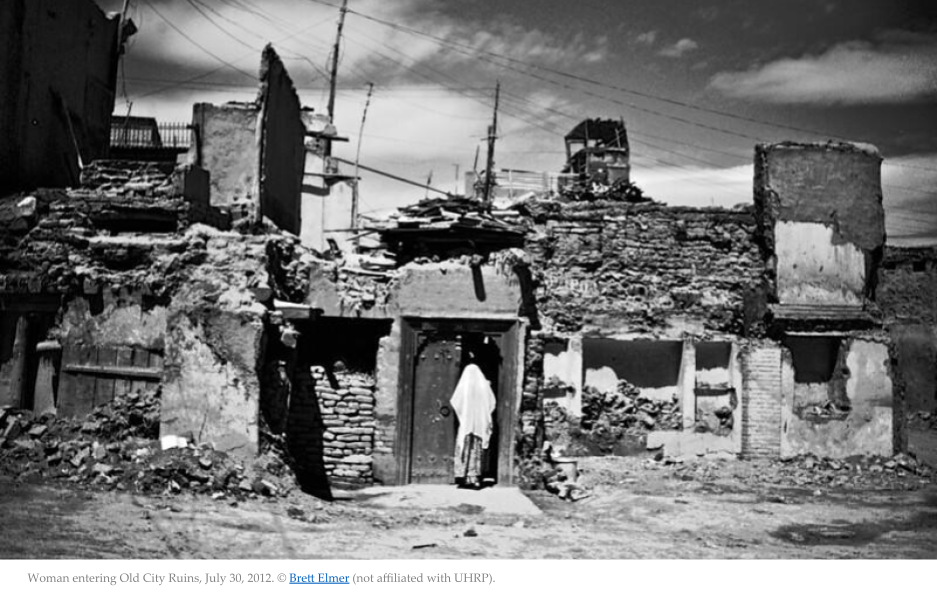

Where satellite data gives some loose indication of the breadth of demolitions, on-the-ground photos can give a clearer view of the nature of the destruction:

Though it would be difficult to verify, indications suggest that the government was successful in demolishing its planned 85% of the Old City, and likely more, given that it even reconstructed some areas initially slated to be preserved. Indeed, the Global Heritage Network’s (GHA) Site Conservation Assessment Report of Kashgar estimates that 90% of the Old City was destroyed.52Global Heritage Network, “Site Conservation Assessment (SCA) Report, Kashgar Old City, Xinjiang Uyghur

Autonomous Region.” Atmospherically, the effect was totalizing. Not only did the inhabitants go through the devastation of seeing their (sometimes centuries-old) ancestral homes destroyed, those who were able to return saw the city rebuilt in a performative, tourist-friendly shadow of its former self. The process unfolded without any meaningful consultation with the locals affected.53Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Living on the Margins: The Chinese State’s Demolition of Uyghur Communities,” 16–17. Although the Old City did benefit in terms of improved plumbing and electricity, and a small minority did prefer their new relocation apartments, Kashgar’s former way of life and layered architectural history was gone—as were the many who could not afford to return, forced into apartments on the outskirts of town.54Michael Sainsbury, “Uighur Tensions Persist as Old City Demolished,” The Australian, January 6, 2010, https://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/world/uighur-tensions-persist-as-kashgars-old-citydemolished/news-story/724e1652965d0f8ecd0e57515d59e6d2 Moreover, much of what was demolished was not replaced: aside from (at least) one local community mosque, the famous Islamic college, Hanliq Madrassa, renowned for its illustrious history stretching back into the 11th century, was seemingly torn down to make room for an athletic field, for example.55Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Living on the Margins: The Chinese State’s Demolition of Uyghur Communities,” 69. Journalist Nick Holdstock related the new atmosphere this way:

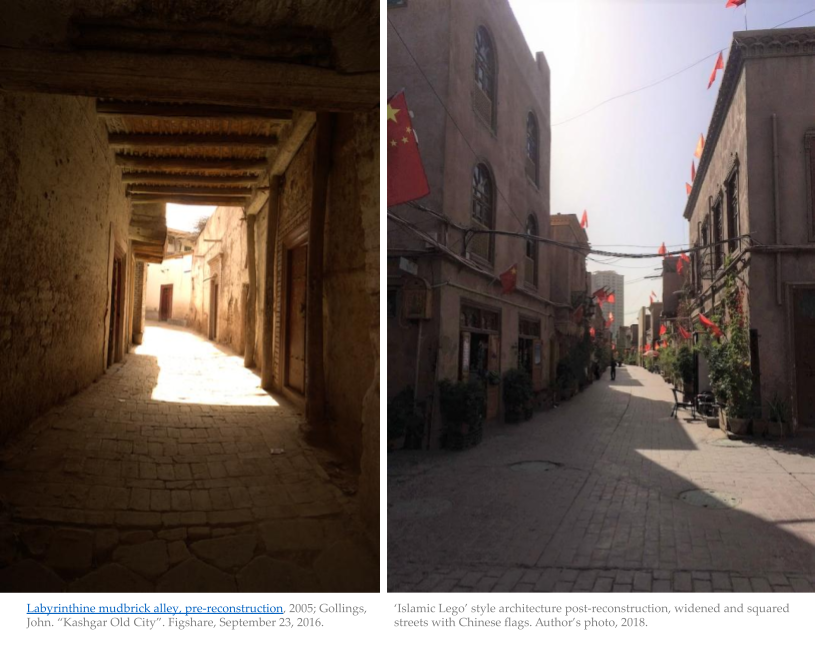

“By the end of 2010 more than 10,000 houses in the Old City had been destroyed. When I visited the city in 2013 it was barely recognisable. Bright ten- and 15-storey buildings lined the eight-lane roads. There were shops selling gourmet cakes, Apple phones and computers, expensive bottles of wine. . . . there were still some landmarks that had been unaffected, like the Id Kah mosque. But in 2000 the mosque had been the hub from which noisy, chaotic streets of traders radiated. Now the shops near the Id Kah are housed in new buildings whose architectural style could be described as Islamic Lego: blocky, light-brown structures graced with ornamental arches. Above their doors are wooden signs saying ‘Minority Folk Art’ or ‘Traditional Ethnic Crafts’ in English and Chinese. . . . It was not until climbing Yar Beshi, a hill in the east of the city, that I understood the scale of the destruction. The path leading up was thick with dust, dust that had been houses, homes: despite being one of the two main sections designated for protection, large areas of Yar Beshi have been completely razed. From the top I could see a panorama of clay- and white-coloured six-storey buildings, more of which will probably fill the huge area— around ten city blocks—that have been cleared at the foot of the hill. It was strange to see such a vast open space in the heart of a city; it was as if there’d been some kind of disaster. . . . The most finished houses were the ones on the streets behind the Id Kah, which resemble a kitsch fantasy of a southern-European street. The houses and the road bricks were complementary shades of terracotta; the balconies and doors were made from wood that had a plastic sheen. . . . The houses on the fantasy street looked to have been built using the construction style common all over China. Quickly laid brick is smoothed over with concrete and then a skin of white (or terracotta) tiles applied. The aim isn’t to make a durable building, just to make a building fast.”56Holdstock, China’s Forgotten People, chap. 7.

Holdstock’s words paint a valuable picture of the far-reaching effects of Kashgar’s reconstruction, which not only destroyed the irreplaceable, world-class mud-brick architecture of the city, but also (and more fundamentally) ripped apart the socio-cultural ecosystem facilitated by that architecture—built on long centuries of tradition. Community life in the Old City became fundamentally transformed, and the pivotal role that Kashgar had played in Uyghurs’ intergenerational cultural transmission was absolutely crippled, with a devastating prognosis for the future of Uyghur society.

2014–present: Re-education Camps and Continued Demolitions

From documents leaked to the New York Times, we now know that the seeds of the current cultural genocide campaign being exacted on the Uyghurs were sown in April of 2014, around the time Xi Jinping made a visit to East Turkistan in the wake of the 2014 Kunming attack. In a now-leaked internal speech, Xi called for the state to use “the organs of dictatorship” to show “absolutely no mercy” in the “struggle against terrorism, infiltration and separatism” in East Turkistan. 57Austin Ramzy and Chris Buckley, “‘Absolutely No Mercy’: Leaked Files Expose How China Organized Mass Detentions of Muslims,” The New York Times, November 16, 2019, sec. World, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/11/16/world/asia/china-xinjiang-documents.html The results have been catastrophic, unleashing a campaign of ubiquitous cultural destruction; extrajudicial mass internment, indoctrination, and torture; gulag-style forced labor camps; and the birth of a truly unprecedented surveillance state. The bulk of these developments began in earnest around 2016, when Tibet’s Party Secretary, Chen Quanguo, was transferred to East Turkistan, though the pressure had already been on the rise since Xi’s 2014 visit. From that point on, much of what has been exacted on Kashgar can be seen in the context of this broader, concerted campaign. However, this campaign can also be seen for many of its many continuities with what had gone before in Kashgar. Thus, for the purposes of this report, I will examine the various facets of the 2014–present campaign in the context of what had gone before in Kashgar—particularly as it relates to construction and reconstruction of the city itself.

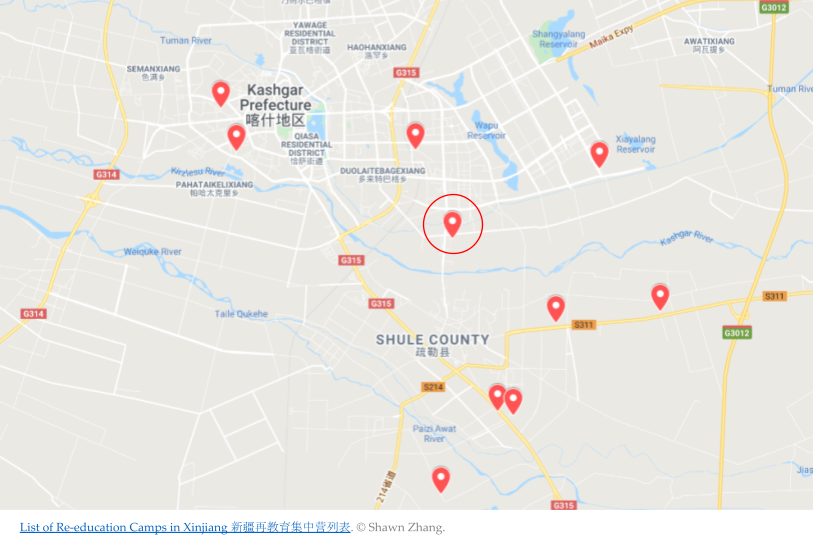

Between 2014 and 2016, the screws of state oppression were already tightening in significant ways. Incarceration rates for minorities in East Turkistan were rising, as was surveillance and securitization, with devastating effects. When considering the reconstruction of Kashgar, however, it is fair to say that the construction and refurbishment of buildings as re-education camps can be seen as another sort of “reconstruction,” the next step in changing the face of the city. The open-source research work of Shawn Zhang shows approximately 10 known re-education camps in the area of Kashgar (including adjacent Yengishaher [Chinese: Shule] County).588 For more information, see Shawn Zhang, “Satellite Imagery of Xinjiang ‘Re-Education Camp’ №17, 18, 19 新 疆再教育集中营卫星图 17, 18, 19,” Medium, September 22, 2018, https://bit.ly/2XWGVTt; Shawn Zhang, “Satellite Imagery of Xinjiang ‘Re-Education Camp’ №2 新疆再教育集中营卫星图 2,” Medium, September 29, 2018, https://bit.ly/2MoP5yE; Shawn Zhang, “Satellite Imagery of Xinjiang ‘Re-Education Camp’ №35 新疆再 教育集中营卫星图 35,” Medium, September 9, 2018, https://bit.ly/2Bsce0T; Shawn Zhang, “Satellite Imagery of Xinjiang ‘Re-Education Camp’ №51 新疆再教育集中营卫星图 51,” Medium, September 22, 2018, https://bit.ly/3dsVk0f; Shawn Zhang, “Satellite Imagery of Xinjiang ‘Re-Education Camp’ №40 新疆再教育集 中营卫星图 40,” Medium, September 12, 2018, https://bit.ly/2XQWiwJ; Shawn Zhang, “Satellite Imagery of Xinjiang ‘Re-Education Camp’ №15 新疆再教育集中营卫星图 15,” Medium, September 25, 2018, https://bit.ly/3gQftj0; Shawn Zhang, “Satellite Imagery of Xinjiang ‘Re-Education Camp’ №13 新疆再教育集中 营卫星图 13,” Medium, October 19, 2019, https://bit.ly/2U2yYL4; Shawn Zhang, “Satellite Imagery of Xinjiang ‘Re-Education Camp’ №3 新疆再教育集中营卫星图 3,” Medium, October 19, 2018, https://bit.ly/2Xpt3lo

Zhang’s impressive work demonstrates how old schools and factories were transformed and expanded with watch-towers, barbed wire, and new living facilities to facilitate the mass internment of East Turkistan’s Uyghur (and other Turkic) peoples. Though some may have been abandoned, or only constructed with temporary use in mind, the map (above) shows the positioning of the known camps around Kashgar. One particularly well-documented camp (circled in red above) is shown below (p.33) with wired fences and watchtowers highlighted.

The external appearance of the camp can be seen depicting watchtowers, barbed wire, and bars over windows (p.34).

The secrecy surrounding these camps has made understanding what goes on in each particular facility a challenge. As a collective, however, a combination of first-hand accounts and open-source journalism has begun to piece together a more comprehensive picture in what continues to be a highly dynamic and evolving situation.59For an impressive and continuously updated bibliography, see Magnus Fiskesjo, “Bibliography of Select News Reports & Academic Works” (Uyghur Human Rights Project), accessed February 22, 2020, https://uhrp.org/featured-articles/chinas-re-education-concentration-camps-xinjiang Between 1–3 million (likely at least 1.8 million)60Joshua Lipes, “Expert Says 1.8 Million Uyghurs, Muslim Minorities Held in Xinjiang’s Internment Camps,” Radio Free Asia (blog), November 24, 2019, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/detainees11232019223242.html Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities have been detained in extrajudicial centers— excluding the large number already incarcerated. The most recent estimate of 1.8 million would equate to about 15.4% (or almost one– sixth) of the adult Turkic and Hui population, and probably includes far more camps than are currently known.61Lipes. In the second half of 2018, there seems to have been a movement from detention camps into forced labor programs that maintain significant continuities with the camps (to be discussed in the next section).62Lipes. Within the camps, reports confirm a systematic attempt to erase Uyghur (and other minorities’) culture in favor of aggressive Chinese assimilation,63Christian Shepherd, “Fear and Oppression in Xinjiang: China’s War on Uighur Culture,” Financial Times, September 12, 2019, https://www.ft.com/content/48508182-d426-11e9-8367-807ebd53ab77 including mandatory Mandarin language study, forced indoctrination, torture,64Rob Schmitz, “Ex-Detainee Describes Torture In China’s Xinjiang Re-Education Camp,” NPR (blog), November 13, 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/11/13/666287509/ex-detainee-describes-torture-in-chinasxinjiang-re-education-camp severe sexual violence,65David Stavrou, “A Million People Are Jailed at China’s Gulags. I Managed to Escape. Here’s What Really Goes on Inside,” Haaretz, October 17, 2019, https://www.haaretz.com/world-news/.premium.MAGAZINE-amillion-people-are-jailed-at-china-s-gulags-i-escaped-here-s-what-goes-on-inside-1.7994216 involuntary sterilizations,66Elizabeth M. Lynch, “China’s Attacks on Uighur Women Are Crimes against Humanity,” Washington Post, accessed February 22, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2019/10/21/chinas-attacks-uighurwomen-are-crimes-against-humanity/ deaths, and mass organ harvesting.67Adam Withnall, “China Is Killing Religious and Ethnic Minorities and Harvesting Their Organs, UN Human Rights Council Told,” The Independent, September 24, 2019, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/china-religious-ethnic-minorities-uighur-muslim-harvestorgans-un-human-rights-a9117911.html The camps represent brutal centers of coercion and cultural genocide.

As we consider the camps in the context of Kashgar as a whole, it is notable that they are dispersed around the periphery of the city, removed from its literal and symbolic center. Similarly, save their barbed-wire, the buildings tend to be relatively discreet, fenced, and in less-populated areas. Nonetheless, the threat of the camps hangs over the city: an unspoken, hidden reality that literally and figuratively frames the life of the city. Without warning, individuals and even whole neighborhoods have been known to silently disappear into the camps, leaving behind an absence—and a warning—that is palpable.

The development of the camps themselves has progressed in tandem with increased camp-like practices of indoctrination and surveillance throughout East Turkistan (to be further elaborated in the next sections). As these practices relate to the physical reconstruction of the city, however, it is important to note how they have been implemented alongside continuing alterations to the material architecture of the city. Since 2014, for instance, the Chinese government deployed 200,000 Party cadres to regularly visit and surveil Turkic groups throughout East Turkistan; since December 2017, the program expanded to include a “Becoming Family” initiative, a compulsory program through which more than a million cadres spend at least five days every two months in the homes of East Turkistan’s Turkic residents.68Human Rights Watch, “‘Eradicating Ideological Viruses’ | China’s Campaign of Repression Against Xinjiang’s Muslims” (Human Rights Watch, September 9, 2018), https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/09/09/eradicating-ideological-viruses/chinas-campaign-repression-againstxinjiangs Though these specific programs are more directed at rural Uyghurs, similar practices of more invasive government intervention and surveillance extended into Kashgar. The result is that just as some communal practices and rhythms were necessarily destroyed with the traditional architectures of the Old City, the reconstructed “new” Old City arrived in lockstep with new, stateinduced rituals of Chinese allegiance and Han engagement. Between 2014 and 2018, Uyghur attendance at local, weekly flag-raising ceremonies throughout the city and at Chinese language and culture classes swelled, as mosque attendance plummeted. Likewise, a tradition of periodic “Red Song” contests has taken root, with troupes of Uyghurs being recruited to participate in officially staged cultural activities aimed to publicly display state allegiance.69Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Extracting Cultural Resources: The Exploitation and Criminalization of Uyghur Cultural Heritage” (Uyghur Human Rights Project, June 12, 2018), 24, https://uhrp.org/pressrelease/extracting-cultural-resources-exploitation-and-criminalization-uyghur-cultural As the Old City was forcibly reconstructed, so were community practices.

Indeed, many of these new practices were further reinforced through continued changes to the architecture of the city since 2014. In a shockingly swift and under-reported process, the 2016 “Mosque Rectification” campaign of Kashgar demolished nearly 70% of mosques in Kashgar over the course of just three months, by the government’s own admission. A Radio Free Asia investigation suggested that more than 5,000 mosques were destroyed in the process.70Shohret Hoshur, “Under the Guise of Public Safety, China Demolishes Thousands of Mosques,” trans. Brooks Boliek (Radio Free Asia, December 19, 2016), https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/udner-theguise-of-public-safety-12192016140127.html Reports suggest that many, perhaps most, of the remaining 30% of mosques have fallen into disuse. As researcher Joanne Smith Finley recounts, in June of 2018 the Old City’s “neighborhood mosques were empty, their ornate doors padlocked, their boundaries decked in razor wire. Residents confirmed that the doors had been permanently closed for over a year. Some mosque walls sported framed copies of the ‘Regulations on Deextremification’ adopted on March 29, 2017, or the ‘Clauses on Work to Improve Ethnic Unity’ of May 3, 2016.” Many mosques had crescents removed, and one was even transformed into a bar for Han tourists named “The Dream of Kashgar,” as if to mock Kashgar’s legacy, HanUyghur exploitation, and the Islamic prohibition against alcohol in one fell swoop.71Joanne Smith Finley, “‘Now We Don’t Talk Anymore’: Inside the ‘Cleansing’ of Xinjiang,” ChinaFile (blog), December 28, 2018, https://www.chinafile.com/reporting-opinion/viewpoint/now-we-dont-talk-anymore

Rather than neighborhoods radiating out from organically dispersed mosques, Kashgar’s neighborhoods now radiate out from systematically planned “convenience police stations,” parts of the “grid-management system” that divides each city into squares of 500 people to be monitored by these hubs of surveillance and social control.72“China Has Turned Xinjiang into a Police State like No Other,” The Economist, May 31, 2018, https://www.economist.com/briefing/2018/05/31/china-has-turned-xinjiang-into-a-police-state-like-no-other In this sense, the new network of police stations replace the old mosques both geographically and functionally as spatial representations of community order: the former according to principles of community religion and tradition, the latter around principles of state coercion and compliance. A similar displacement and reordering are also mirrored in the symbolic community heart of Uyghur culture, Id Kah Square. Opposite the centuries-old face of the iconic mosque is a towering LED screen scrolling through gigantic images of Xi Jinping.

The situation continues to develop, with new changes to the city every day. In a recent, disturbing development, the last remaining traditional neighborhood of Kashgar’s Old City seems to be under threat. Known in Chinese as Gaotai Minju, the Kozichi Yarbeshi neighborhood rests on a hill outside the old city wall and was left as the single remaining vestige of traditional Old City architecture.

Upon visiting Kashgar in October of 2018, this author visited the neighborhood during the day to find guards covering all entrances, and at night, at which time he was able to gain access. Though the site was formally closed to tourists between 2016–2018, early morning and night visits were common practice for tourists hoping to see the last preserved section of the Old City. Locals I spoke with were certain that I would find a vibrant night market and community past hours, as online travelers’ blogs confirmed. Upon entering, I discovered disturbing signs of recent eviction, including large X’s spray-painted on doors, missing electrical boxes, refuse in the streets, padlocked doors, and a complete absence of people:

Recent photos by one tour guide from the region confirm the presence of heavy demolition machinery near the neighborhood:

The neighborhood in question was famous for housing stalwarts of Uyghur culture who resisted Old City reconstruction with notable fervor. While getting any reliable information out of Kashgar is a challenge today, indications do not look promising. At a time when whole neighborhoods have been known to disappear into detention camps, the sudden and unreported desertion of the historic neighborhood suggests a likely forced removal into camps. The deteriorating condition of the neighborhood in combination with nearby demolition equipment also suggests that the last remaining holdout of Kashgar’s traditional architecture may not last long.

Taken as a whole, the ongoing process of reconstruction in Kashgar represents a totalizing campaign of literal and symbolic cultural destruction and cooptation. Not only has the world lost an irreplaceable city of immense historical significance, the Uyghur people have lost their spiritual capital and the socio-cultural ecosystem that it sustained for centuries. More than simple destruction, the vestiges of Kashgar have been symbolically reconstructed into a new sociocultural ecosystem, complete with new edifices and community practices that approximate what came before for legitimacy, but which are ultimately directed towards forced assimilation and control. The life of the city as a whole has become framed geographically by a network of hellish “re-education” camps constructed around the city, supporting the aggressive campaign of sociological and urban transformation the Chinese government has pursued. Unlike the longsince destroyed city walls that once protected Kashgar from external invasion, this new encirclement holds Kashgaris hostage to the processes of cultural genocide. This process is ongoing, as seen in the case of the Kozichi Yarbeshi neighborhood, and also has been replicated in other historic neighborhoods in East Turkistan.73Clément Bürge and Josh Chin, “After Mass Detentions, China Razes Muslim Communities to Build a Loyal City,” Wall Street Journal, March 21, 2019, sec. World, https://www.wsj.com/articles/after-mass-detentionschina-razes-muslim-communities-to-build-a-loyal-city-11553079629 As we shall see, it has also been intertwined with powerful mechanisms of economic exploitation and surveillance that have further contorted the life and history of the city.

VI. Economic Exploitation

Until recently, the processes of commercialization and economic exploitation at work in Kashgar have in many respects paralleled trends of commercialization that have plagued many historic cities and ethnic minority groups, albeit in a particularly aggressive form. The demolition of the Old City, intertwined with these trends, certainly elevated the severity of this cultural exploitation to an extreme. Recent reports of forced labor from detainees, however, suggest a final, distinct state of China’s economic exploitation of East Turkistan: abject extraction.

The factors that have contributed to Kashgar’s economic exploitation are manifold. For one, East Turkistan’s geographical features and natural resources are particularly coveted by the Chinese state. Natural oil (20% of China’s overall oil intake) and coal (40%)74Zachary Torrey, “The Human Costs of Controlling Xinjiang,” The Diplomat, October 10, 2017, https://thediplomat.com/2017/10/the-human-costs-of-controlling-xinjiang/ across East Turkistan have made the region important to the Chinese government and its state owned enterprises, creating in many areas of East Turkistan a state-owned, company-led mass migration of Han Chinese into traditionally Uyghur lands, and domination over Uyghur economies.75Edward Wong, “China Invests in Region Rich in Oil, Coal and Also Strife,” The New York Times, December 20, 2014, sec. World, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/21/world/asia/china-invests-in-xinjiang-region-rich-inoil-coal-and-also-strife.html China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is predicated on effective westward economic expansion, making East Turkistan a huge national economic priority as an important nexus of trade and commerce between China and the rest of Eurasia. Kashgar, with its unique proximity to Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, is thus a priority for China’s long-term economic strategy, and, for individual investors in China, a city of significant economic opportunity. Compounding this “opportunity” is the unique cultural heritage of Kashgar at a time in which Chinese domestic tourism— particularly “ethnic-minority tourism”—has been on the rise, laying the groundwork for a massive operation of cultural commodification. As Chen Quanguo’s devastating campaign of cultural erasure and mass detentions has progressed, the allure of forced labor for profit from Kashgar’s Uyghur-heavy urban context has produced an additional form of economic coercion and extraction that is unprecedented within the city.

The results of these processes have been manifold and mutually reinforcing. First, Kashgar has seen significant demographic shifts, with influxes of Han Chinese residents that local Kashgaris estimate to be in the hundreds of thousands—not reflected in official government statistics.76Spencer, “Fibre of Silk Road City Is Ripped Apart.” Second, East Turkistan as a whole has seen soaring economic inequality along ethnic lines and a rising cost of living, especially in areas like Kashgar. Third—now undoubtedly severely exasperated by practices of forced labor—a vicious cycle of economically based inter-ethnic resentment has emerged. Fourth, despite some improvements to basic infrastructure, the Uyghur population has endured a brutal loss of human dignity through the combination of economic marginalization in their homeland, Han-managed cultural commodification, and systematic economic exploitation.

Whereas the story of Kashgar’s concerted architectural reconstruction began around 2000, the economic exploitation of Kashgar had earlier roots, linked to Chinese state attempts to gain demographic advantage in the region. In some ways this process dates as far back as 1830, when the Qing dynasty began encouraging Han Chinese to set roots down in East Turkistan in order to give the empire greater power in the region.77Tyler, Wild West China, 186. The Republic of China attempted various schemes of economic incentivization for Han settlers, with limited success, just as the early Communist regime sent thousands of “volunteers” at various junctures to settle in East Turkistan,78Tyler, 168. along with approximately 800,000 famine refugees between 1959 and 1960 from the disastrous Great Leap Forward campaign.79Susan Wong-Tworek, “China’s Economic Development Plan in Xinjiang and How It Affects Ethnic Instability” (Naval Postgraduate School, March 2015), 10, https://calhoun.nps.edu/handle/10945/45276 Prior to 1999, however, the primary flag-bearer of Han migration to East Turkistan was the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, or Bingtuan, a curious hybrid of a state-owned enterprise and paramilitary force founded in 1954 with a stated mission to “reclaim land and garrison the frontier, populate the . . . borders of Xinjiang . . . with a Han population engaged in economic activities in times of peace.”80Liu and Peters, “The Hanification of Xinjiang, China,” 266. The unusual threefold purpose of the Bingtuan—military “security,” Han settlement, and economic development—speaks volumes to the government’s unabashed manipulation of economic development to exploit and coerce East Turkistan and its inhabitants. As of 2018, the Bingtuan alone accounted for 2.68 million residents of Xinjiang and 17% of GDP, with an increasingly dominant role in state law enforcement and terror.81Uyghur Human Rights Project, “The Bingtuan: China’s Paramilitary Colonizing Force in East Turkestan” (Uyghur Human Rights Project, April 26, 2018).

In the 1980s, waves of Han migrants began taking up residence in East Turkistan, particularly in the more industrialized north of the region.82Wong-Tworek, “China’s Economic Development Plan in Xinjiang and How It Affects Ethnic Instability,” 39. In 1999, after several decades of increasing Bingtuan-pioneered Han migration, a new stage of Han emigration began under the Great Leap West campaign, a massive government initiative of Chinese state investment in western provinces—East Turkistan chief among them.83Liu and Peters, “The Hanification of Xinjiang, China,” 267. Airports, railway lines, and telecommunications were expanded with a budget of approximately 100 billion RMB (just over USD$12 billion in 1999) in the first year alone, accompanied by a narrative of modernizing remote and backwards ethnic minorities and utilizing untapped natural resources.84Liu and Peters, 267. Many locals felt as though the program brought a veritable deluge of Han migrants to the region,85Spencer, “Fibre of Silk Road City Is Ripped Apart.” infamous for a culture of transactional exploitation of local land, people, and economic systems.86Wong-Tworek, “China’s Economic Development Plan in Xinjiang and How It Affects Ethnic Instability,” 36–40. Whereas China’s 1953 government census found that Han Chinese made up 6% of East Turkistan’s population, the 2000 census listed the Han population at 40.57%. By the same censuses, Uyghurs had declined from 75% to 45.21% of the population (though absolute population numbers increased).87Congressional-Executive Commission on China, “Xinjiang Reports High Rate of Population Increase,” February 28, 2006, https://www.cecc.gov/publications/commission-analysis/xinjiang-reports-high-rate-ofpopulation-increase The Great Leap West naturally only intensified these trends. While the region’s GDP has risen significantly alongside migration, it has largely risen along ethnic lines, with Han Chinese dominating high-skilled and well-paying jobs, and Uyghurs left predominantly in low-skilled, rural jobs. Naturally, the influx of new, unequal wealth has also raised the costs of living, often making it more difficult for Uyghurs to continue their lifestyles on the same budget. Ethnic-based job discrimination has been severe, and resentment has accordingly grown.88Wong-Tworek, “China’s Economic Development Plan in Xinjiang and How It Affects Ethnic Instability,” 41–

45.

It is within this broader context that we must consider Kashgar’s economic situation. Though Kashgar is situated in the more Uyghur-majority southern side of East Turkistan (most Han migrants have settled to the north), it has long been home to a slightly higher proportion of Han inhabitants than its immediate surrounding areas due to its key strategic position.89Dillon, Xinjiang and the Expansion of Chinese Communist Power, 3. That said, in 1952, of the 97,160 inhabitants of Kashgar recorded in the first PRC census of the city, the vast majority were Uyghur. By the 1980s, due in part to many of the aforementioned policies, the population of 190,000 had shifted to 73% Uyghur and 26% Han—a dramatic change, partially facilitated by Kashgar’s designation in 1984 as a grade-two open city because of its key strategic position near the Soviet Union.90Dillon, “Religion, Repression, and Traditional Uyghur Culture in Southern Xinjiang,” 2–3. Through the 1990s, immigration to Kashgar intensified, further encouraged by the construction of a new railway line that opened Kashgar to more Han settlers, who were allured by the profits and strategic location awaiting development in the far west.91Hammer, “Demolishing Kashgar’s History.” The jobs and industry they founded were generally dominated and almost entirely staffed by Han workers,92Hammer. especially in the better-paid industries of construction, resource extraction, and manufacturing.93Tyler Harlan, “Private Sector Development in Xinjiang, China. A Comparison between Uyghur and Han,” Espace populations sociétés, no. 2009/3 (December 1, 2009): 407–18, https://doi.org/10.4000/eps.3772

Thus, migration patterns throughout the 1980s and 1990s had already begun to change the shape of Kashgar—Old City reconstruction aside. As Nick Holdstock relates, by 2000, the city “was already two places. . . . Walking between tall white-tiled buildings, past shops selling engine parts, steamed dumplings and fireworks, was like being in a small town in Hunan province, 5,000 kilometres to the east.”94Holdstock, China’s Forgotten People, chap. 7. Nonetheless, turning off the main streets would still take one away from commercialized Han Kashgar, and back into a more organic Uyghur atmosphere.95Holdstock, chap. 7. Driven by a government seeking greater ethnic assimilation and free-market forces, Han settlers to Kashgar effectively began building a parallel economy that would slowly transform the city, enveloping its culture, architecture, and traditional economy.

Naturally, the reconstruction of the city accelerated this process profoundly, as we have seen. Looking at the reconstruction through an economic prism, however, there are important additional elements not to be missed. For one, the reconstruction effectively amounted to a significant government-induced gentrification of the Old City, such that many Uyghurs could not afford to move back to their homes. The Uyghurs who were wealthy enough to return after reconstruction “tend[ed] to be the wealthier ones, government employees and successful merchants whose economic well-being depends on their cooperation with the Han-dominated authorities,96Dan Levin, “China Remodels an Ancient Silk Road City, and an Ethnic Rift Widens,” The New York Times, March 5, 2014, sec. World, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/06/world/asia/china-remodels-an-ancient-silkroad-city-and-an-ethnic-rift-widens.html”skewing the culture and ethos of the Old City. Likewise, interviews with locals suggest many of those who were moved out from the Old City were also moved far away from their means of economic livelihood, creating a dependency on government benefits, for which demonstrated submission to state policies of assimilation and community reporting were prerequisite—further eroding the cultural and community norms of the Old City. In this way, multiple methods of governmental economic coercion have tended to operate in lockstep with reconstruction policies, subtly reinforcing the methods of state economic control alongside the more obvious reengineering projects of the symbolic heart of Kashgar.

Immediately following the reconstruction of Kashgar, the neighborhood Communist Party committee of the Old City leased the reassembled heart of Uyghur culture to the Beijing Zhongkun Investment Group, a Han company which began marketing the area as a “living Uyghur folk museum.”97Levin. The corporation established a “nearmonopoly” over Kashgar’s tourism,98Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Living on the Margins: The Chinese State’s Demolition of Uyghur Communities,” 65. with the few surviving original homes often designated with signage and agreements of being a “family especially for visiting” by tourists.99Uyghur Human Rights Project, 38. Indeed, the Old City as a whole seems to have been redesigned with an eye to better conditions for surveillance on one hand, and tourism on the other,100Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Extracting Cultural Resources: The Exploitation and Criminalization of Uyghur Cultural Heritage,” 39. and in many ways has become a gigantic theater for extracting wealth from commodified Uyghur tradition. So aggressive was the commercial tourist interest in the city that it even occasionally butted up against state policies of religious repression. In the case of Id Kah mosque (and others), for instance, a charge for entry is levied on both Han tourists and Uyghur worshippers—but only after a debate by local authorities as to whether to define all such worship as “illegal religious activity and feudal superstition” or as a potential opportunity to be “exploited as a tourism resource following the model of the commercialization of Tibetan religious culture.”101Uyghur Human Rights Project, 28. It is equally worth noting that many cultural traditions and activities have been forcibly fused with state propaganda or Han traditions.102Uyghur Human Rights Project, 3. A full exploration of Uyghur cultural exploitation can be found in UHRP’s “Extracting Cultural Resources” report,103See Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Extracting Cultural Resources: The Exploitation and Criminalization of Uyghur Cultural Heritage.” For a more thorough treatment of the issue. but suffice it to say that the dynamics are clear, and particularly exaggerated in the case of Kashgar: Uyghur culture is a resource to be commodified and extracted, for profit and for social control. Kashgar’s Old City today has become a menagerie of performative Uyghur cultural traditions largely in the service of Han wealth production and state social control—from its synthetic ‘Islamic lego’ architecture, to its cultural performances, to its ownership.

Uyghur culture is a resource to be commodified and extracted, for profit and for social control. Kashgar’s Old City today has become a menagerie of performative Uyghur cultural traditions largely in the service of Han wealth production and state social control.