Future CCP Propaganda Versus “No One Dared to Mention the Dead”

January 14, 2025

A UHRP Insights column by Ben Carrdus, UHRP Senior Researcher

How has the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) tended the gaping chasm between propaganda and reality in China’s modern history? And what do earlier historical precedents of propaganda around past atrocities bode for future propaganda on East Turkistan?

This is not intended to be a comparison of atrocities perpetrated by the CCP throughout its history. Instead, this is an attempt to foresee how China’s propaganda on the Uyghur Region may develop based on how the Party has historically whitewashed the disasters it has inflicted on China.

For now, the CCP’s mission to propagandize a fairyland version of East Turkistan continues apace. Along with vast amounts of content in the domestic media and sponsored content abroad, the CCP’s messaging also appears in traveling exhibitions, in “conferences,” in carefully stage-managed media and diplomatic tours of the region, and at travel shows where people are invited to “unveil the truth” about the region.

Despite the best efforts of the Department of Propaganda,1The Department of Propaganda is an entity within the CCP as opposed to being a government agency; however, it is instituted within the State Council, or cabinet, putting it on a par with government ministries. In CCP-translated materials “Department of Propaganda” is more routinely rendered as “Department of Publicity,” reflecting an awareness that the term “propaganda” in English and other languages is mostly pejorative. The State Council Information Office – Beijing’s formal media communications agency for the outside world – is the Department of Propaganda by another name. global awareness of atrocities in East Turkistan ensures the CCP’s legacy in the region—if only for the last decade, let alone the last 75 years—is a stain every bit as haunting and indelible as the Tiananmen Massacre.

A basic metric for the scale of oppression is that Uyghurs (at barely one percent of China’s national population) comprise up to 60 percent of China’s entire prison population. Up to half of all imprisoned journalists in China are Uyghur. Uyghurs are the most likely of all inmates to die in prison. Coercive family planning policies have led to an alarming crash in the number of Uyghur births, worse even than the rates during genocides in Cambodia and Rwanda. There is evidence that forced labor programs in the Uyghur Region are expanding. Expressions of faith and cultural identity have been criminalized. But the Party would have us believe that Uyghurs are “the happiest Muslims in the world.”

History as propaganda

Party-branded history forms the essence of day-to-day Party propaganda. A famous adage states that journalism is the first rough draft of history. Conversely in China, “journalism”—communications and propaganda—is dictated and proof-read by Party historians and ideologues.

Since the CCP’s founding over a hundred years ago, controlling how China’s history is told and interpreted has been one of the Party’s most fundamental tools for claiming and asserting its legitimacy. In its own telling, the Party’s monopoly on political power is an “historical inevitability” and therefore its inalienable birthright. The Party brands any dissension from the CCP’s versions of history as “historical nihilism” which is “tantamount to denying the legitimacy of the CCP’s long-term political dominance.”

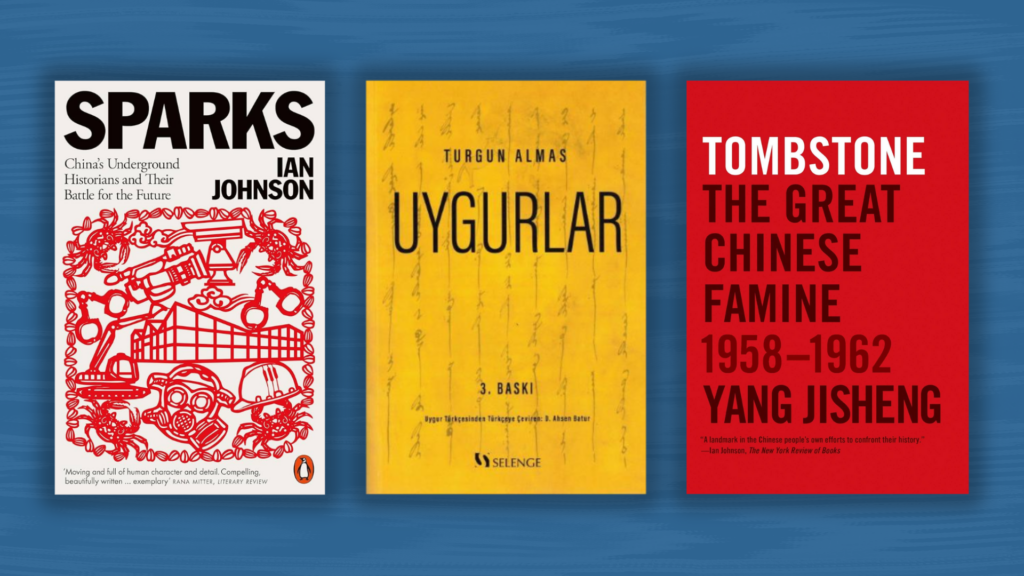

In his fascinating book Sparks: China’s Underground Historians and Their Battle for the Future, Ian Johnson writes that the stakes for such dissension are high: “Xi Jinping has made control of history one of his signature policies – because he recognizes counter-history as an existential threat.”

Standalone Uyghur histories are not tolerated: Uyghurlar by poet and historian Turghun Almas was quickly banned after its release in 2010. In early 2022, Sattur Sawut, a historian who drew on previous official versions of the Uyghur Region’s past was given a suspended death sentence for a history book he compiled, and three of his associates were given life sentences.

The Party-line history insists that the Uyghur Region has been part of “the Motherland” since the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD), and that the Uyghur people—along with all ethnicities in the Uyghur Region—have been “members of the same big family” ever since. In other words, the Uyghur people, their land and their culture are all just scions of a greater Chinese entity. The absurd use of the metaphor of a pomegranate to describe the closeness of all ethnic people in the region is far more descriptive of Uyghurs crammed into prison cells.

And it is the CCP’s mission to wrench the Uyghur people into a state of being that affirms this telling of history as narrated by the propaganda which largely fuels human rights atrocities in the region.

Propaganda and the Great Chinese Famine, 1958 to 1962

The Great Chinese Famine is widely regarded as the worst man-made disaster in human history. Absurdly ambitious agricultural policies were pursued to ridiculous lengths. Claims of outrageously high crop yields were championed by the Party, which then turned a willfully blind eye to the devastation their policies caused to food production. Even as people starved to death in plain sight the Party’s focus was instead on celebrating its own genius and exacting brutal recrimination against anyone who dared doubt it.

Estimates for the numbers of people who died in the famine vary between 2.6 and 55 million. One of the most rigorous studies—Tombstone: The Great Chinese Famine, 1958-1962 by former Xinhua journalist Yang Jisheng—estimates 36 million people died while another 40 million “failed to be born” due to falling birthrates.

Yang quotes Lu Baoguo, a Xinhua journalist at the time, who recounts: “In the second half of 1959, I took a long-distance bus from Xinyang to Luoshan and Gushi [in Henan Province]. Out of the window, I saw one corpse after another in the ditches. On the bus, no one dared to mention the dead.”

More than 60 years later, official accounts of the period gloss over the famine as “The Three Years of Hardship” (三年困难时期). At the time of writing, the top result from a Google search of the “gov.cn” domain using the term “The Three Years of Hardship” is a 2015 article from the “Party History Research Office of the CCP Yueyang Municipal Committee” in Hunan, which states: “In 1959, 1960, and 1961, there were three consecutive years of natural disasters coupled with the Soviet Union’s debt collection and leftist ideological interference, and the country entered a difficult period and the people lived in hardship.”2The same article quotes discussions by local Party leaders at the height of the famine on the “grim situation” faced by people in their rural part of Hunan Province, lamenting: “Our great leader Chairman Mao did not eat a piece of pork for 90 days.” Hunan was one of the worst-hit provinces in China with 8% of the population starving to death. Anhui Province, where 18% died, was the worst hit. The famine was less devastating in East Turkistan; by some accounts, refugees from China fled to the oasis towns of East Turkistan where there were still reserves of grain and dried fruit. (Johnson, p. 68.)

The famine is “completely absent” from China’s history textbooks; Yang Jisheng hasn’t been permitted to leave China to accept awards for Tombstone, which hasn’t even been published in China.

Continuing to whitewash and doctor the historical record will inevitably form the foundation of the CCP’s future propaganda strategy on East Turkistan. Given the framing of the Great Chinese Famine, the closest the Party may ever come to acknowledging, for example, the astronomical rates of Uyghur imprisonment—up to one in 17 adults—will be a similarly trivializing non-confession: “The Party displayed an abundance of caution in the face of challenging domestic and international pressures, which led in some areas to an over-enthusiasm for intensive education measures.”

However, in these days of mass communication and social media contributing to the mountain of evidence documenting the ongoing genocide, not mentioning the dead will unavoidably be read between every line of the propaganda.

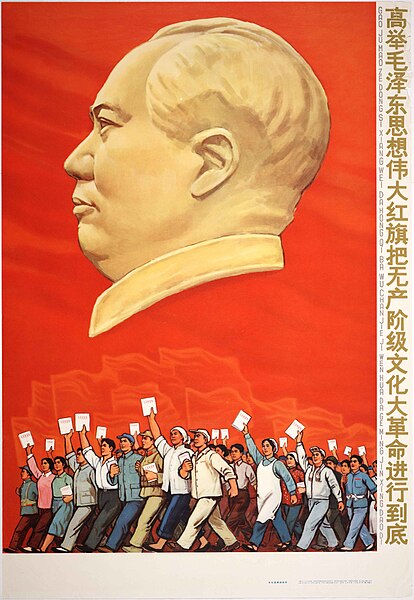

Propaganda and the Cultural Revolution, 1966 to 1976

Most readers of this article are probably broadly aware of the history of the Cultural Revolution. For those who are not, the best explanation is that it’s impossible to explain. The CCP too is at a loss—“Ten Years of Chaos” is about the best it’s come up with.

In terms of propaganda, there seems to be a tentative bargain between the CCP and most of China’s population, a mutual tacit acknowledgment that a political mania exploded across the PRC in 1966, but for which the institution of the CCP must not be blamed. Instead, it’s largely individuals who are held culpable—radical Red Guards, the Gang of Four, and even Chairman Mao to a limited degree. That the Cultural Revolution was an epochal trauma to a society of hundreds of millions of people cannot be too closely examined, nor can the fact that the devastation wrought in East Turkistan and Tibet was worse than that in China.3The Cultural Revolution brought such harrowing devastation to East Turkistan that Party Chairman Hu Yaobang – seen as a reformer after the death of Mao – wanted to dissolve the bingtuan, accused by Uyghurs as being the primary vehicle for China’s decimation and exploitation of the Uyghur Region. He also apologized to the Tibetan people during a visit to Lhasa in 1981.

Yes, the Party may admit that the Cultural Revolution was a “mistake,” but it is very quick to move on. Professor Su Wei, a writer on a committee that compiles history textbooks for schools has said of the Party’s role in the Cultural Revolution, “The CCP recognized its mistake, fixed it and achieved success in another way, which comes with China’s reform and opening-up.” End of discussion.

And in case there’s any doubt, Professor Su claims the Party itself was also, actually, a victim: “[The Cultural Revolution] brought catastrophe to the Party [listed first], the country and the whole people.”

This truce of convenience between the CCP’s chagrin and people’s common awareness of history would almost certainly never work in East Turkistan. The social and intellectual spaces where Chinese people can knowingly shrug at the Party’s historical misrule are largely closed to Uyghurs. There has been no “social contract” between the Party and the Uyghur people. Whereas the Party can tolerate popular Chinese nostalgia and even hawk official Disney-fied Cultural Revolution tourism, there is no such tolerance for Uyghurs reflecting on their traumas.

Professor Su concludes, “After generations of people being calm, we will be able to review the Cultural Revolution more objectively.” There’s no reason to assume he wouldn’t conclude the same on the plight of the Uyghur people. He doesn’t say how many generations, nor who needs to be calm, nor why. What he is saying, quite categorically, is that the Party intends to continue denying justice for generations to come.

The Tiananmen Massacre, June 3–4, 1989

The CCP Department of Propaganda’s central offices are a short tank-drive from Tiananmen Square itself—merely half a city block—and anyone there would certainly have witnessed the massacre, if they chose to.4The Director of the Propaganda Department in 1989 was Wang Renzhi, a career scholar of communist ideology and policy. His next posting in 1992 was to be appointed Party Secretary and Vice President of the Party-run think-tank, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

It’s well-known that the Department of Propaganda is adept at flooding online spaces with counter narratives and disinformation. However, the department’s other primary function is brute censorship. Every year around the anniversary of the massacre, huge volumes of material attempting to discuss or memorialize events are liable to be wiped from China’s cyberspace.

Online postings containing any one of hundreds of keywords are considered suspect. Some of the keywords are obvious: “tank man” or even just “tank,” for example. Others are a stark demonstration of the CCP’s nervousness: postings containing “candle” are suspect because some of the bereaved light candles in memory of those killed. Still other keywords are evidence of people’s ingenuity and determination to memorialize the massacre: posts containing the otherwise meaningless characters 占占点 are deleted because the characters are intended as a pictogram of tanks rolling over people.

That the Party was willing to turn the military forces of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army against unarmed Chinese citizens was a shock that still reverberates around the country 35 years on. And whereas the Party’s stance on other events may have softened over the years – some incidents are “reassessed” by Party historians and individuals once vilified are posthumously “rehabilitated” – there has been no significant deviation in the Party’s refusal to countenance any kind of public accounting for the Tiananmen Massacre.

This same absolutist stance typified by the application of mass censorship largely prevails on a day-to-day basis in East Turkistan, and will likely do so for many years to come. Such are the levels of police surveillance and censorship that Uyghurs’ entire online presence and activities are routinely recorded and analyzed for just the potential of crossing China’s extremely high bar for Uyghur criminality. There are reports that Uyghurs are forbidden from downloading various popular social media apps, including TikTok, and detained for the “pre-crime” of downloading the popular messaging app WhatsApp.

The desired effect of the CCP’s propaganda and censorship regime is largely being achieved: no unsanctioned Uyghur voices are being heard from inside East Turkistan.

Conclusion

The CCP employs—and will undoubtedly continue to employ—various tried and tested propaganda strategies in East Turkistan. The lesson from the Great Leap Forward is how to make the record invisible, the Cultural Revolution is a lesson in blaming others, and the Tiananmen Massacre a lesson in outright denial and the utility of the delete key. These same strategies are evident in other atrocities not covered in this article: the decimation of Tibet, the murderous campaign against Falun Gong, or the Party’s mishandling of the Covid outbreak, to name but a few.

The continuation of a people’s culture depends on the validity of their memories and experience. The challenge of maintaining the integrity of Uyghur identity is falling ever harder on the diaspora, notwithstanding the CCP’s concerted efforts to harass and silence Uyghurs abroad. This is a mission that’s well understood in the diaspora and among their supporters, but greater assistance against Beijing’s vast propaganda machine is always welcome.

Propaganda is neither a science nor an art, and for over a century there has been no true innovation in Chinese propaganda. The paradigm shifts of digital media and mass communications haven’t altered the basic impulse: dominate or destroy narratives in support of ulterior motives. As Chairman Mao put it, “Make the past serve the present.” But perhaps Churchill put it more succinctly: “History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it.”