A Uyghur Human Rights Project report by Elise Anderson. Read our press statement on the report here, and download the full report in English and 日本語. Cover art by YetteSu.

Key Takeaways

- In September 2021, authorities in Ayagh Chigetugh village, Yanduma township, East Turkistan, formally rolled out the “Pomegranate Flower Plan,” an initiative to match Uyghur children and children of other ethnic groups in China as “pomegranate pairs.”

- The Pomegranate Flower Plan builds on earlier attempts by the Chinese party-state to reengineer Uyghur life, in part through coercing “kinship” relationships between Uyghurs and members of other ethnic groups—particularly Hans. These “kinship” relationships operate on a fundamental imbalance that places Hans above Uyghurs in political, economic, and social hierarchies.

- UHRP is deeply concerned that Uyghur participants are given no choice in the decision to take part in this program, which violates their cultural and linguistic rights as well as rights to family life, unity, and privacy.

- We recommend that analysts and journalists monitor Chinese state media and social media for information about the program.

I. Introduction

Since the beginning of the mass internment campaign in East Turkistan in 2017, outside observers have expressed concern about the impacts of the humanitarian crisis on Uyghur children.1Two terminological notes: 1) We refer to the government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as the “party-state” or “Chinese party-state” as a way of emphasizing one-party rule in China and highlighting the difficulties in distinguishing between state and party apparatuses, policies, and actions. 2) We refer to the Uyghur homeland alternately as “East Turkistan” and the “Uyghur Region.” A vast majority of Uyghurs prefer these toponyms to those of “Xinjiang” and the “Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region,” which they see as offensive colonial terms. In cases where we refer to particular publications or government offices and apparatuses, however, we use “Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region” or related forms such as “XUAR” or “Xinjiang.” Ample evidence has emerged to show that Uyghur children have been deeply affected by the crisis. Children have been forcibly separated from their parents, institutionalized in orphanages and boarding schools, and placed in educational settings where they are not allowed to produce and consume knowledge in their native language. Authorities have also rolled out policies intended to prevent the births of future generations of Uyghur children, a fact which ultimately led the Uyghur Tribunal to issue its December 2021 judgment that the actions of the Chinese party-state rise to the level of genocide.2Uyghur Tribunal, Summary Judgment as delivered at Church House Westminster, December 9, 2021, https://uyghurtribunal.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Uyghur-Tribunal-Summary-Judgment-9th-Dec-21.pdf

In this briefing, we present evidence that Chinese party-state efforts to intervene in and re-engineer Uyghur life continue unabated in East Turkistan. Specifically, we use evidence culled from Chinese state media and social media to introduce and discuss the Pomegranate Flower Plan (PFP). The PFP, an officially backed local-level initiative to foster “kinship” between Uyghur children from East Turkistan and children of other ethnic groups from across the People’s Republic of China (PRC), was introduced in a township in Kashgar prefecture in September 2021 and appears to be operating only in this location as of January 2022. Examining this local initiative gives us a chance to zoom into the experience of daily life in East Turkistan’s townships and villages, which have long been sites of tight surveillance and control. The PFP gives insight into how local leaders adopt slogans and implement policies inspired by the top of the political hierarchy, as well as how those leaders use the means of governance to control Uyghur lives.

II. The Pomegranate Flower Plan

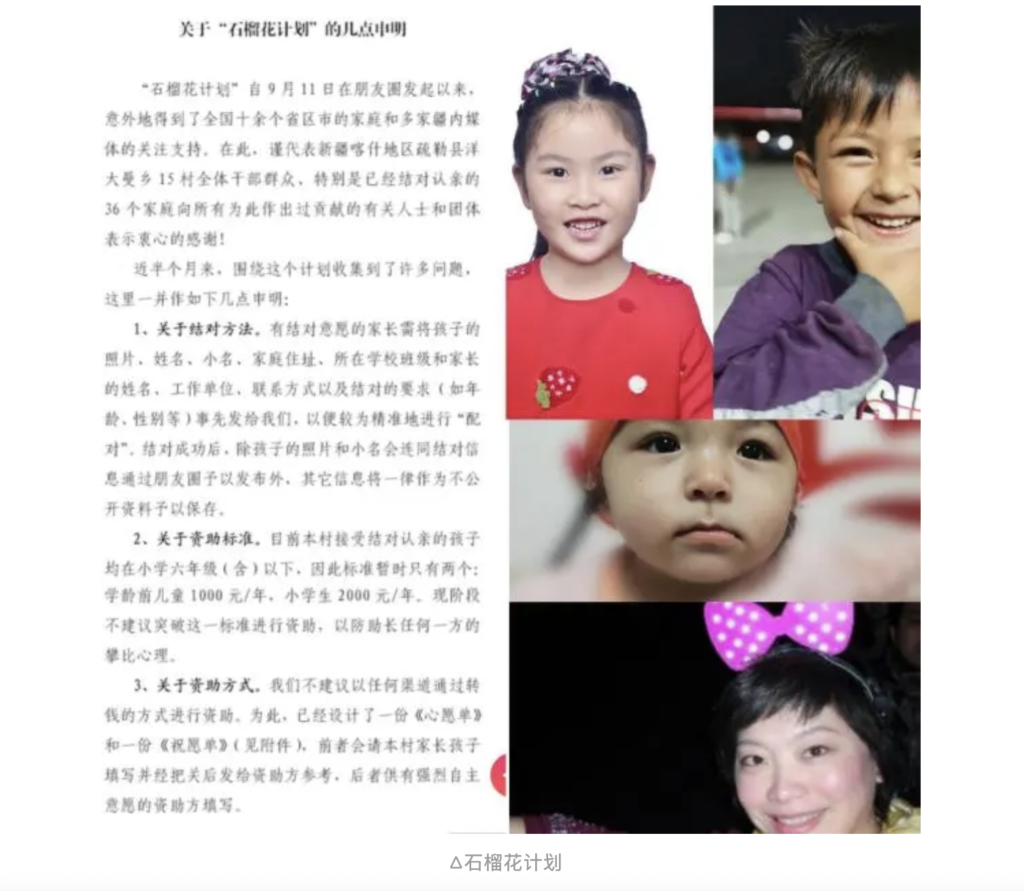

On September 24, 2021, a state media outlet in East Turkistan published an article announcing the successful launch of the then-new “Pomegranate Flower Plan” (Ch: 石榴花计划; Uy: Anar güli pilani). According to the article, published on the government-run Tianshan website and attributed to reporter Kang Haoyan, the PFP pairs Uyghur children with children from across the PRC as “family.”3Kang Haoyan, “南疆小村开出36对’石榴花’” [36 pairs of ‘pomegranate flowers’ have bloomed in a small village in southern Xinjiang], Xinjiang Daily, September 24, 2021, http://news.ts.cn/system/2021/09/24/036701428.shtml (archived at https://archive.ph/vzonB). Uyghur language translation by Xinjiang Daily available here: http://uy.ts.cn/system/2021/09/24/036702125.shtml (archived at https://archive.ph/dRUEU)

The PFP gives insight into how local leaders adopt slogans and implement policies inspired by the top of the political hierarchy, as well as how those leaders use the means of governance to control Uyghur lives.

In October 2021, Radio Free Asia’s Uyghur service broadcast a brief program about the PFP prepared by Gulchehra Hoja based on evidence from Chinese state media sources.4“Xitay «anar güli pilani» ni yolgha qoyup, Uyghur gödeklirini Xitay ölkiliridikiler bilen «tughqanlishish» qa mejburlighan” [China launches the “pomegranate flower plan,” forces Uyghur children to “become family” with people in the Chinese provinces], Radio Free Asia, October 14, 2021, https://www.rfa.org/uyghur/xewerler/anar-guli-pilani-10142021194705.html. The Uyghur-language program then became the basis of a report published by the English service of RFA, which to date is the only non-Chinese source to have reported on the initiative.5“Chinese government targets Uyghur children with ‘pomegranate flower’ policy,” Radio Free Asia, October 21, 2021, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/pomegranate-flower-program-10212021092622.html

Meanwhile, the Xinjiang Daily reporting has been recycled and quoted in other news outlets as well as in numerous WeChat accounts, including in a post to 最后一公里 (“The last kilometer”), the official account of the United Front Work Department in the XUAR.6“每个角落都有民族团结故事” [In every corner, stories of ethnic unity], 最后一公里 [WeChat], October 6, 2021, archived at https://archive.ph/DkVDU#selection-41.64-44.0 Tianshan also posted a version of the article with photos of some PFP participants to its official WeChat account on September 24.7“南疆小村开出36对’石榴花,” Tianshan [WeChat], September 24, 2021, https://archive.ph/JwWop

We have yet to locate the original advertisement for the program, which was reportedly circulated via WeChat Moments by an unnamed entity on September 11, 2021. According to Kang’s article in the Xinjiang Daily, however, the advertisement was popular: the September 24 article notes that a total of 36 pomegranate flower “pairs” were successfully matched within two weeks of the WeChat post. The 36 local children hail from Ayagh Chigetugh village, Yamandang township, in Kashgar prefecture’s Yengisheher county. (We presume the children are Uyghur given the majority status of Uyghurs in this area.) Their “matches”—all of whom are Han save one ethnic Tibetan boy from Tibet—hail from a total of 30 different locations across 13 provinces, autonomous regions, and cities in the PRC. Available evidence suggests that the program has been rolled out only in Ayagh Chigetugh village under the leadership of Zhu Pengcheng, who has been assigned to the post of village party secretary by the XUAR People’s Government.8A November 2, 2021, article posted to the WeChat account of a Wuhan University organization claims that a group of students visiting Ili Prefecture learned about the Pomegranate Flower Program put into place there. However, the numbers and other details they cite are lifted straight from the numbers referenced in state media reporting about the PFP in Ayagh Chigetugh village. See https://archive.ph/S8j9I The coverage of the PFP in state media sources suggests that the initiative has the endorsement of the regional government.

Kang’s article makes clear that the program is intended to be a vehicle for the sharing of “culture” between the children, and specifically notes that “brothers” and “sisters” across the PRC sent their “relatives” in East Turkistan gifts including mooncakes in celebration of the Mid-Autumn Festival. However, there is no sign that cultural exchange flows the opposite way in the program. In other words, Uyghur children participating in the PFP do not appear to be teaching Han and other children about the distinct linguistic, cultural, and religious practices of Uyghurs.

The coverage of the PFP in state media sources suggests that the initiative has the endorsement of the regional government.

Available information shows that parents of PFP participants outside East Turkistan voluntarily signed their children up for the program upon seeing the September 11 advertisement on WeChat Moments. We have found no clear evidence regarding how the Uyghur children were chosen for participation in the program. However, language in the article hints at a link between party-led led “poverty alleviation” initiatives and the PFP, noting that this particular township was only successfully “alleviated” from poverty in 2020. It goes on to suggest that local children participating in the PFP might have been chosen based on financial need—specifically, a need for “warmth” from their Han brothers and sisters. Language about “poverty alleviation” has long provided euphemistic cover for rights violations in East Turkistan, as across the PRC; in recent years, the same language has also become an indicator for camp internment and forced labor.9For example, see Zhao Yusha, “Xinjiang relocates 460k residents,” Global Times, July 7, 2018, archived at: https://www.pressreader.com/china/global-times-weekend/20180707/281500752007219. We suspect that the “relocation” of these residents via “poverty alleviation” schemes was cover for rights abuses by the party-state. See also: Adrian Zenz, “Beyond the Camps: Beijing’s Long-Term Scheme of Coercive Labor, Poverty Alleviation and Social Control in Xinjiang,” Journal of Political Risk vol. 7 no. 12, December 10, 2019, https://www.jpolrisk.com/beyond-the-camps-beijings-long-term-scheme-of-coercive-labor-poverty-alleviation-and-social-control-in-xinjiang/ A weekly report posted to the WeChat account of the Shanghai Municipal Group (SMG) Research Institute, dated October 11, 2021, gives more information about the “development” and financial dimensions of the PFP. The report links the PFP to an initiative known as “Civilizing Xinjiang” (文化润疆), giving a glimpse into development-style projects targeting East Turkistan. The weekly report also reveals that the non-local families participating in the program are providing material and financial assistance to the local children in East Turkistan, and that at least one regional government office has given its seal of approval to the program.10【文化润疆】SMG文化润疆志愿者周报第三、四周 [(Civilizing Xinjiang) SMG “Civilizing Xinjiang” Volunteer Weekly Report, Weeks Three and Four], SMG思研汇 [WeChat account], October 11, 2021, archived at https://archive.ph/ZrO94#selection-49.25-99.1

Evidence also makes it explicit that the program has political dimensions. For example, Kang’s Xinjiang Daily article links the program name, “Pomegranate Flower Plan,” directly to a 2014 statement by Xi Jinping at the National People’s Congress. Kang cites Ayagh Chigetugh party secretary Zhu Pengcheng as saying,

General Secretary Xi Jinping said that all ethnic groups must cluster together like pomegranate seeds. We have launched an initiative to pair children from Xinjiang and children from other provinces in China as family. We hope the children will form a deep friendship from a young age, so that they will feel the warmth and kinship of living in the big family of our motherland.11Kang, “南疆小村开出36对’石榴花.’”

Zhu’s statement, which draws on a statement from a 2014 speech by Xi (discussed in more detail below), implies that the program might represent a local-level attempt to please superiors higher up in the party-state apparatus. Other coverage of the PFP in articles posted to official WeChat accounts explicitly links the program to other ongoing efforts to coerce “kinship” between Uyghurs and Hans. For instance, a post to the United Front magazine account includes the PFP as one of three exemplars of “unity” and “harmony” in the Autonomous Region in the past year.12“像石榴籽一样紧紧抱在一起——新疆各族干部群众眼中的这一年” [Holding each other tightly like pomegranate seeds—this year in the eyes of cadres and people of all ethnic groups in Xinjiang], UFWD Magazine [WeChat account], September 29, 2021, archived at https://archive.ph/MdiQ1#selection-45.64-48.0

Other coverage of the PFP in articles posted to official WeChat accounts explicitly links the program to other ongoing efforts to coerce “kinship” between Uyghurs and Hans.

On the surface, the program might appear harmless: for Hans and Uyghurs to provide financial assistance to one another and for Uyghur and Han children to become friends could indeed be good things. However, in the current environment in East Turkistan, where Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other Turkic Muslim peoples face punitive measures for small infractions, there is virtually no way for Uyghurs to refuse participation in party-state schemes. We are deeply concerned that the Pomegranate Flower Plan is little more than a vehicle of assimilation and thus a continued violation of Uyghurs’ cultural and linguistic rights as well as rights to family life, unity, and privacy.

III. The PFP and Party-State Policies in East Turkistan

Available evidence points to non-superficial connections between the PFP and the wider political context of East Turkistan. One of the clearest examples of this lies in the name Pomegranate Flower Plan itself. Pomegranates—in particular, their seeds—have emerged as a ubiquitous symbol for the unity of ethnic groups in the region as well as the PRC. Pomegranate seeds became explicitly political in May 2014, when Xi delivered a speech at the second Xinjiang Work Forum in Beijing in which he

urged all ethnic groups in Xinjiang to “show mutual understanding, respect, tolerance and appreciation among themselves, and learn and help each other,” so that they could be united together “like seeds of a pomegranate.”13“Central government pledges better governance in Xinjiang,” Xinhua, May 30, 2014, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2014-05/30/content_17552753.htm

The same speech emphasized the importance of “Xinjiang residents” (i.e., Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other local Turkic, majority-Muslim groups) seeing themselves as part of the Chinese nation, as well as a need for exchange between groups, bilingual education, and the diminishing of the importance of the ethnic group—all in the name of “ethnic mingling” as a political directive.14James Leibold, “Xinjiang Work Forum Marks New Policy of ‘Ethnic Mingling,’” Jamestown, China Brief 14 (12), June 19, 2014, https://jamestown.org/program/xinjiang-work-forum-marks-new-policy-of-ethnic-mingling/. The concept of “ethnic mingling” or “ethnic consolidation” has long been a goal of the party-state, as reflected in the influential work of scholars and policy makers such as Ma Rong. A full examination of this concept is beyond the scope of the current briefing.

That the 2021 program unveiled in Ayagh Chigetugh village bears the name of such a significant political symbol is unlikely to be a coincidence.

The pomegranate seed has been used as a metaphor for “unity” across the PRC since 2014, but the trope has taken on a particular relevance and ubiquity in East Turkistan, where pomegranate-themed propaganda slogans and images began appearing ad nauseum in 2017. Xi has gone on to repeat “like seeds of a pomegranate” in other contexts, including in a meeting of the National People’s Congress in March 2017 as well as in a speech before the 19th National Congress in October of the same year.15An Baijie, “‘Cherish ethnic unity,’ president tells Xinjiang,” China Daily, March 11, 2017, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2017twosession/2017-03/11/content_28515253.htm16Xi Jinping, “Secure a Decisive Victory in Building a Moderately Prosperous Society in All Respects and Strive for the Great Success of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” Speech before 19th National Congress, October 2017, available in English translation at International Department, Central Committee of CPC website, https://www.idcpc.org.cn/english/cpcbrief/19thParty/index.htmlPropaganda signs featuring the trope were displayed widely around East Turkistan, and an ethnic-Uyghur official, Erkin Tuniyaz, repeated the trope in a speech before the UN in 2019 when he said,

The Xinjiang people of all ethnic groups share weal and woe, achievements of reform and development featuring equality, solidarity, harmony and mutual assistance. They are united as closely as the seeds of a pomegranate.17“Address at the 41st Session of the Human Rights Council,” Aierken Tuniyaz (Erkin Tuniyaz), Member of the Standing Committee of CPC Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Regional Committee and Vice Governor of Xinjiang People’s Government, delivered in Gene on June 25, 2019, available at https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/supporting_resources/aierken_tuniyazi_hrc41.pdf. See also Sophie Richardson, “Pomegranate Propaganda,” Human Rights Watch, June 26, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/06/26/pomegranate-propaganda-chinese-government-officials-un-speech. Mr. Erkin’s name has been rendered multiple ways in English-language press, including Erken Tuniyaz, Aierken Tuniyaz, Alken Tuniaz.

That the 2021 program unveiled in Ayagh Chigetugh village bears the name of such a significant political symbol is unlikely to be a coincidence.

The coerced kinship of the PFP also echoes a series of the home-visit and homestay programs—what anthropologist Darren Byer calls “village-based cadre team programs”18Darren Byler, “China’s Government Has Ordered a Million Citizens to Occupy Uighur Homes. Here’s What They Think They’re Doing,” ChinaFile, October 24, 2018, https://www.chinafile.com/reporting-opinion/postcard/million-citizens-occupy-uighur-homes-xinjiang—that have been rolled out in East Turkistan from 2014 into the present. The first of these was the 访惠聚program, more frequently rendered as “Becoming Family” in English language reporting on the crisis.19Fanghuiju (访惠聚) is a shortened form of “访民情、惠民生、聚民心”, which literally translates as “Visit the People, Benefit the People, and Bring Together the Hearts of the People.” For more on the program, including primary-source handbooks in Chinese, see “‘Hundred Questions and Hundred Examples’: Cadre Handbooks in the Fanghuiju Campaign,” Xinjiang Documentation Project [University of British Columbia], no date, last accessed January 10, 2022, https://xinjiang.sppga.ubc.ca/chinese-sources/cadre-materials/cadre-handbooks/ Beginning in 2014, the program dispatched civil servants (ethnic Hans and Uyghurs alike) to the townships and villages to perform political work. A companion program targeting the families of prisoners was launched in 2016, and third home-visit program, which dispatched more than one million primarily Han “family member cadres” into Uyghur homes, was then launched in 2017. These homestay programs have effectively served as projects in human surveillance. Cadres have been instructed explicitly to ask children about families’ religious practices and daily lives during play because “children will not lie.”20“XX单位开展“四同”“三送”活动工作手册” [Launching the “Four Togethers” “Three Sends” Initiative Work Unit XX Handbook], (2018): 3, hosted at https://livingotherwise.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/%E2%80%9C%E5%9B%9B%E5%90%8C%E2%80%9D%E4%B8%89%E9%80%81%E6%B4%BB%E5%8A%A8%E6%89%8B%E5%86%8C.pdf. The “four togethers” of the initiative are eating together, living together, laboring together, and studying together. The “three sends” (i.e., what cadres will give to Uyghur families) are warmth, law, and policy. See also Darren Byler, “China’s Government Has Ordered a Million Citizens to Occupy Uighur Homes.” Homestay programs have also reinforced institutionalized hierarchies whereby Hans retain a place of social, political, and cultural dominance over their Uyghur “kin.” Some first-hand accounts have suggested that homestay programs have also facilitated the sexual and other abuse of Uyghurs, particularly women and children.21For one example, see “Male Chinese ‘Relatives’ Assigned to Uyghur Homes Co-sleep With Female ‘Hosts’,” Radio Free Asia, October 31, 2019, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/cosleeping-10312019160528.html

The unidirectional flow of cultural “exchange” from Han children to Uyghur children in the PFP parallels the monolingual nature of “bilingual” schooling models for Uyghur children in East Turkistan. Uyghurs’ rights to educate their children in their native language have eroded significantly over the past several decades, with a particular acceleration since 2004. Space for knowledge production and consumption in the Uyghur language has diminished as new phases in “bilingual” education have been rolled out in the region. In effect, the education system has become a primary site for the party-state engineering of the hearts and mind of young Uyghurs, a phenomenon UHRP has documented extensively over the past decade.22For example, see Rustem Shir, “Resisting Chinese Linguistic Imperialism: Abduweli Ayup and the Movement for Uyghur Mother Tongue-Based Education,” Uyghur Human Rights Project, May 16, 2019, https://uhrp.org/report/resisting-chinese-linguistic-imperialism-abduweli-ayup-and-movement-uyghur-mother/ As of 2022, there is virtually no space of privilege for the Uyghur language in the East Turkistan school system, and the party-state continues to invest vast resources into forcibly assimilating Uyghur children. That a program like the PFP would reinforce the privilege of Chinese language and culture over Uyghur language and culture is as unsurprising as it is devastating.

The unidirectional flow of cultural “exchange” from Han children to Uyghur children in the PFP parallels the monolingual nature of “bilingual” schooling models for Uyghur children in East Turkistan.

Perhaps the starkest examples of the party-state’s targeted assimilation of Uyghur children come in the form of orphanages and other boarding facilities built to house the children of parents who were detained following the start of the mass internment campaign.23Diaspora Uyghurs often refer to these institutions as “children’s camps,” owing to the way the institutions make Uyghur children as unfree as their detained adult relatives. In 2017 alone, a single county in Kashgar prefecture built a total of 18 new facilities to board Uyghur children full time.24Emily Feng, “Uighur children fall victim to China anti-terror drive,” Financial Times, July 9, 2018, https://www.ft.com/content/f0d3223a-7f4d-11e8-bc55-50daf11b720d In the years since, the existing system of boarding schools within East Turkistan expanded. Reporting by RFA suggested that all kindergartens in Qaraqash County had been turned into boarding schools by early 2020,25“Boarding Preschools For Uyghur Children ‘Clearly a Step Towards a Policy of Assimilation’: Expert,” Radio Free Asia, May 6, 2020, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/preschools-05062020125428.html and research into forced labor in East Turkistan in 2019 showed that the children of Uyghurs forced into labor were placed into state care programs while their parents worked.26Adrian Zenz, “Break Their Roots: Evidence for China’s Parent-Child Separation Campaign in Xinjiang,” Journal of Political Risk vol. 7 no. 7, July 4, 2019, https://www.jpolrisk.com/break-their-roots-evidence-for-chinas-parent-child-separation-campaign-in-xinjiang/ Figures compiled by Adrian Zenz on the basis of Chinese government documents estimate that hundreds of thousands of Uyghur children have been placed into some form of state care since 2017. Between 2017 and 2019, the total number of children in boarding schools rose precipitously by 76.9 percent.27Adrian Zenz, “Parent-Child Separation in Yarkand County, Kashgar,” Medium (blog), October 13, 2020, https://adrianzenz.medium.com/story-45d07b25bcad The impact of separating Uyghur children from their families and placing them in institutions where Mandarin is the predominant language ensures their acculturation into a linguistically and culturally Chinese world. Efforts like the PFP ensure that Uyghur children, who are likely already exposed to an almost exclusively Chinese language environment at school, are further exposed to Han language, culture, and norms in non-school time.

IV. Broader Implications

Evidence-based research on the scale and scope of the Uyghur genocide makes clear that virtually no Uyghur is untouched by the campaign that has unfolded in the region. Since 2017 the Chinese party-state’s genocidal campaign in East Turkistan has weakened familial ties, severed community bonds, and eliminated opportunities for the intergenerational transmission of Uyghur lifeways. All Uyghurs, including children, live profoundly unfree lives marked by various forms of party-state intrusion into the most intimate and mundane parts of daily existence.

In this context, we see the local-level Pomegranate Flower Plan as part of an officially sanctioned effort to destroy Uyghur culture and social life, replacing them with coerced kinship based in Mandarin as a common language and love of the party-state as a core value. We are deeply concerned that Uyghur participation in the program is involuntary. We are also concerned that the program violates Uyghurs’ cultural and linguistic rights as well as their rights to family life, unity, and privacy. International conventions spell out the rights of groups such as Uyghurs to practice their own culture and religion as well as use their own language, as in Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and Article 30 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC),28International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, adopted by UN General Assembly resolution 2200A (XXI) of December 16, 1966, entry into force March 23, 1976, https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/ccpr.aspx29Convention on the Rights of the Child, adopted by General Assembly resolution 44/25 of November 20, 1989, entry into force September 2, 1990, https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx and to live in an environment in which all cultures, languages, and practices are equally respected and shared (versus being subservient to a dominant culture and language), as in Article 13 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).30International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, adopted by General Assembly resolution 2200A (XXI) of December 16, 1966, entry into force January 3, 1976, https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cescr.aspx China is a signatory to each of these conventions, as well as a State Party to the ICESCR and CRC.

Programs such as the PFP appear to be directly inspired by political directives from the top levels of the party-state—directives formed with the intent to destroy Uyghurs as a group […]

The current reach of the PFP appears narrow. Nevertheless, we remain worried by the power of local officials throughout East Turkistan to design and implement programs and policies that violate Uyghurs’ fundamental rights and erode their connections to family, culture, and social life. Programs such as the PFP appear to be directly inspired by political directives from the top levels of the party-state—directives formed with the intent to destroy Uyghurs as a group. Thus, we must understand the PFP not in isolation but rather as a component of China’s campaign of genocide. UHRP strongly encourages analysts and journalists to monitor Chinese media and state media for evidence of the Pomegranate Flower Program and related initiatives as it emerges. We also encourage civil society organizations and rights groups to use this evidence as a basis to advocate for the fundamental rights of Uyghurs in grassroots, national, and international arenas.

V. Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to UHRP director of research Henryk Szadziewski for thoughtful reviews of this briefing from conception to the final stages of writing and editing. She also expresses her thanks to UHRP development officer Reece Thompson and senior program officer Peter Irwin for rigorous editing and comments, and to Reece Thompson and Tashken Davlet for their assistance with transcription and translation of some primary sources.

FEATURED VIDEO

Atrocities Against Women in East Turkistan: Uyghur Women and Religious Persecution

Watch UHRP's event marking International Women’s Day with a discussion highlighting ongoing atrocities against Uyghur and other Turkic women in East Turkistan.