Surveillance, Thought Crimes, Children in Custody: The Xinjiang Police Files One Year On

May 24, 2023 | By Omer Kanat, Executive Director, Uyghur Human Rights Project

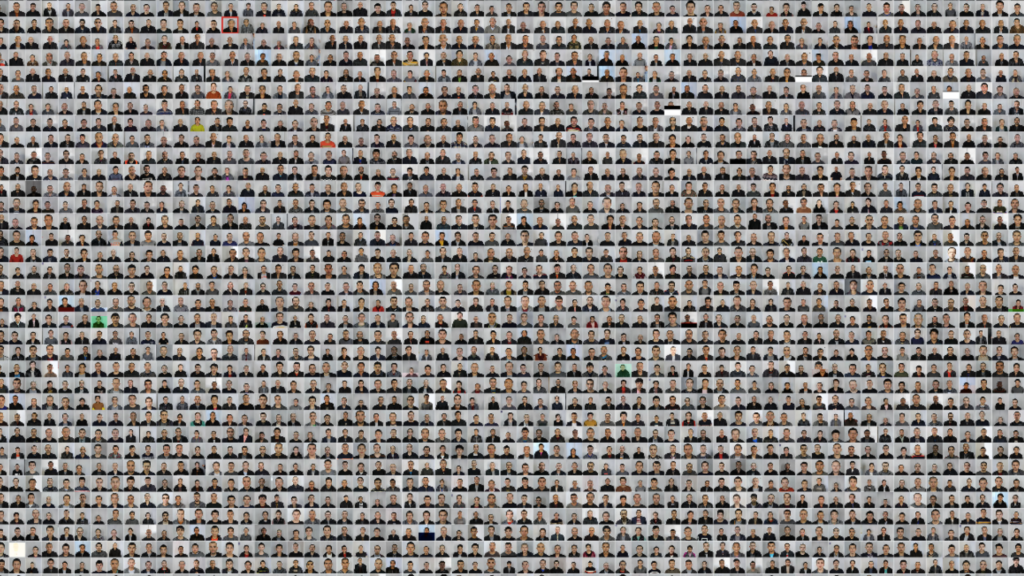

A year ago a consortium of 14 media outlets published the Xinjiang Police Files, a vast collection of documents that includes images, speeches, regulations, and procedures covering China’s vast concentration camp network in East Turkistan. I’d like to ask you to go to the web page titled “Images of Detainees,” brace yourself, and start scrolling. How far can you go while you scan the faces of the people staring back at you before the scale of China’s internment of Uyghurs hits you?

The youngest person with a detainee record in the files was 15 years old. The youngest child with a police photo in the files was six.

The images of hundreds and thousands of people, each with their own human aspirations, families and communities, are just from the counties of Konasheher and Tekes in Kashgar and Ili prefectures. There are 106 county-level divisions in the region. There are 20,000 images of detainees in the Xinjiang Police Files. At one point, estimates put the number of interned Uyghurs at between one to three million. Put another way, between the populations of San Jose and Chicago.

The Chinese government has long denied the existence of concentration camps, but the leaked documents provide irrefutable evidence of their existence and reveal the true nature of these facilities.The evidence presented in the documents is consistent with numerous reports from human rights organizations, academics, and firsthand accounts from former detainees. The Chinese government’s denials ring hollow in the face of such overwhelming evidence.

According to the documents, detainees are subjected to intense ideological indoctrination, forced to renounce their religious beliefs, and taught to pledge loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party. Choose an individual from the thousands of images, perhaps 27 year-old Iminjan Enwer, who was sent to a concentration camp for “religious extremist thoughts.” The so-called crime? From 2012 to 2014, he “worshipped 5 times a day in the basement of the ‘Taixina’ restaurant.”

The Xinjiang Police Files also raise broader questions about the role of technology in authoritarian regimes. China has become a global leader in surveillance technology, with millions of cameras and other monitoring devices installed throughout the country. The use of this technology has enabled the government to exert unprecedented levels of control over its citizens, particularly in regions like East Turkistan where Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples are seen as a threat to the state.

The Chinese government has promoted its surveillance technology as a means of enhancing public safety and maintaining social stability. However, the leaked documents reveal how this technology has been used to suppress dissent and impose conformity. The Chinese government’s use of technology to surveil and control its citizens has far-reaching implications for privacy, free speech, and human rights, not only in China but around the world.

The United States and other countries have already imposed sanctions on Chinese officials and entities involved in crimes against humanity. The release of the Xinjiang Police Files should have galvanized the international community to take even stronger action to hold the Chinese government accountable. However, it has been seven years since we learned about China’s mass internment of Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples and we are no closer to ending the Uyghur genocide.

Our failure to effectively counter China and its extensive propaganda campaigns has effectively enabled an environment where atrocities can occur without adequate intervention. Furthermore, democratic freedoms and values worldwide are under threat from the spread of China’s surveillance model of governance.

The international community has to come together collectively to confront these atrocities.

Governments like Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the European Union—all currently considering mechanisms to address forced labor—must enact import bans on goods from the Uyghur region, similar to the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act in the United States. Multilateral institutions like the International Labour Organization should closely scrutinize forced labor in East Turkistan and take the Chinese government to task for not fulfilling its legal obligations.

Governments should also protect Uyghur citizens and asylum seekers from transnational repression abroad, including from harassment, threats, coercion, and reprisals by Chinese authorities, and publicly affirm a policy to never deport Uyghur refugees and asylum seekers to China. Proactive policies of Uyghur resettlement, along the lines of Canada’s recent parliamentary motion, should be considered to protect those most vulnerable.

One year on, the implications of the Xinjiang Police Files should still be with us. Significantly, the repercussions of our inaction should be clear. The documents provide concrete evidence of the Chinese government’s twenty-first century genocide, and they have been widely condemned by human rights groups and governments around the world. However, there is much more we need to do.

Check out our Chinese language event on May 25, 2023, where panelists will discuss the “Xinjiang Police Files and the effects on the Uyghur diaspora on the one year anniversary.