A Uyghur Human Rights Project explainer by Ben Carrdus; layout and formatting by Peter Irwin. Read our press statement on the explainer, download the full explainer in English, and view a printable, one-page summary of the explainer.

I. Key Takeaways

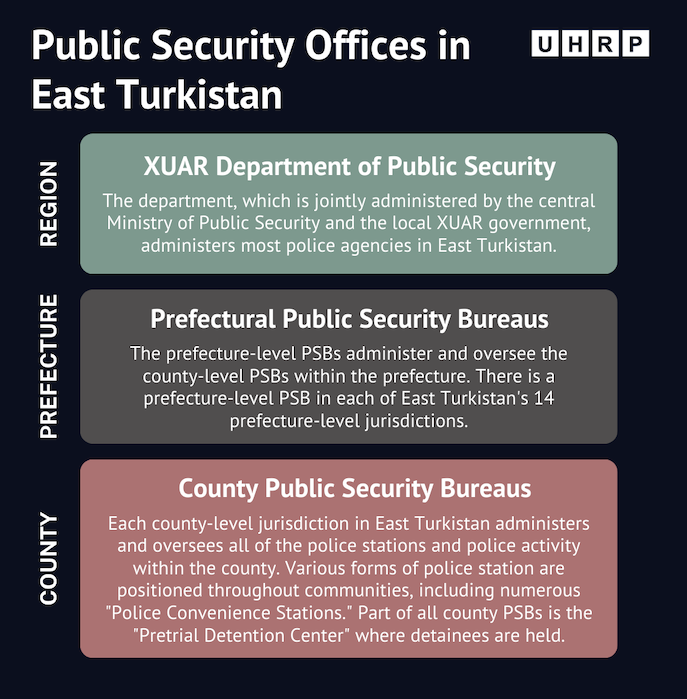

- The police in East Turkistan are among the prime actors in carrying out the genocide arising from the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) policies. Policing in East Turkistan is carried out by several agencies with differing duties and separate command structures, some at the local level and some at the national level, but all ultimately under the CCP’s strict control.

- One of these agencies, the People’s Armed Police (PAP), is commanded by the same CCP committee that controls China’s armed forces, although the PAP is not part of the military.

- East Turkistan has more PAP “Mobile Detachments,” similar to an army regiment, than anywhere else in the People’s Republic of China, possibly twice as many as even Beijing despite having a fraction of Beijing’s population, and they are commanded at the same level as Beijing’s PAP – a grade higher than any other provincial-level administration.

- Regional police, and elsewhere in the PRC, are highly adept and specifically coordinated to tackle perceived affronts to the CCP’s authority, but do not perform well in addressing common crime (such as drug crime).

- According to estimates, there are more than twice as many People’s Police, organizationally similar to state police forces in the US, in East Turkistan than elsewhere in the PRC, plus up to 70,000 Assistant Police (short-term, lesser-trained supplementary officers), on top of an unknown number of PAP troops.

II. Summary

A key detail in building a fuller picture of the ongoing genocide in East Turkistan – the systematic and Party-state-sponsored human rights atrocities perpetrated against Uyghurs and other Turkic people – is to understand the institutions of policing there. While it is accurate to describe “the police” under the strict control of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as a leading actor in the genocide, as opposed to “the army” or “the authorities” or any other state institution, this doesn’t distinguish the various forms of police in East Turkistan, nor their chains of command.

For the purposes of this explainer, “police” refers to the institutions common to all nations and the personnel within those institutions who are ostensibly tasked with detecting and preventing crime and maintaining public order.

East Turkistan has been described as “one of the most heavily policed regions in the world.”1Adrian Zenz and James Liebold, “Securitizing Xinjiang: Police Recruitment, Informal Policing and Ethnic Minority Co-optation,” The China Quarterly, 242 (2020): 324–348, accessed September 27, 2023, online. There are policing agendas in East Turkistan generally not seen elsewhere in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) or certainly not to the same scale, including most notably what the Chinese authorities define as “the three evils” of religious extremism, terrorism, and separatism, which has provided the impetus for decades of severe human rights violations.

Police in East Turkistan have been instrumental in effectively criminalizing the estimated 1.8 million people – close to one in six of the region’s Uyghur and other Turkic people – arbitrarily held in the region’s large network of detention centers since 2016, many of whom are now either formally sentenced to prison, transferred to forced labor programs, or released under intense police surveillance. According to official statistics, despite East Turkistan’s population constituting only 1.5 percent of the PRC’s total, 20 percent of all police arrests in the PRC in 2017 were in East Turkistan.2Tara Francis Chan, “How a Chinese region that accounts for just 1.5% of the population became one of the most intrusive police states in the world,” Business Insider, July 31, 2018, online. Another prominent feature of policing in the region is the ubiquitous and highly invasive surveillance systems, which for the time being at least are not seen on a comparable scale anywhere else in the PRC.3Chris Buckley and Paul Mozur, “How China Uses High-Tech Surveillance to Subdue Minorities,” New York Times, May 22, 2019, online.

According to one conservative estimate, as of 2017, there were 2.3 times more People’s Police (Ch. 人民警察, Renmin jingcha) including Assistant Police and other “security-related positions” in East Turkistan than elsewhere in the PRC: 478 per 100,000 population compared to 212 nationally.4Adrian Zenz and James Liebold, “Securitizing Xinjiang: Police Recruitment, Informal Policing and Ethnic Minority Co-optation,” The China Quarterly, 242 (2020): 324–348, accessed September 27, 2023, online. However, these figures neither include the unknown number of centrally-commanded People’s Armed Police (Ch. 人民武装警察部队, Renmin wuzhuang jingcha budui – see below) in the region, nor include police and paramilitary forces within the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (see below), and nor do they factor in the far-ranging involvement of ordinary local government departments in supporting the police.

The purpose of this explainer is to outline policing structures as they are currently understood with a view to providing a broad overview of the roles that the various forms of police play in the ongoing genocide in East Turkistan.

III. Policing Superstructure in East Turkistan

Oversight and administration of the various policing entities active in East Turkistan is coordinated between various CCP and government bodies.

Party

- Chinese Communist Party (CCP; Ch. 中国共产党, Zhongguo gongchan dang): the CCP is in total control of every single aspect of policing and the judiciary in the PRC. This control is broadly exercised by appointing CCP cadres to leadership positions throughout all of the public security apparatus and judiciary, and more specifically by means of the powerful Central Politics and Legal Affairs Commission.

- Central Politics and Legal Affairs Commission of the Chinese Communist Party (CPLAC; Ch. 中共中央政法委员会, Zhonggong zhongyang zhengfa weiyuanhui): the CCP body which oversees and directs law enforcement in the PRC, including the Ministry of Public Security and the various police agencies within it, as well as the Ministry of State Security and the intelligence services it provides, and the Ministry of Justice, which administers the courts, state prosecution, and prisons.

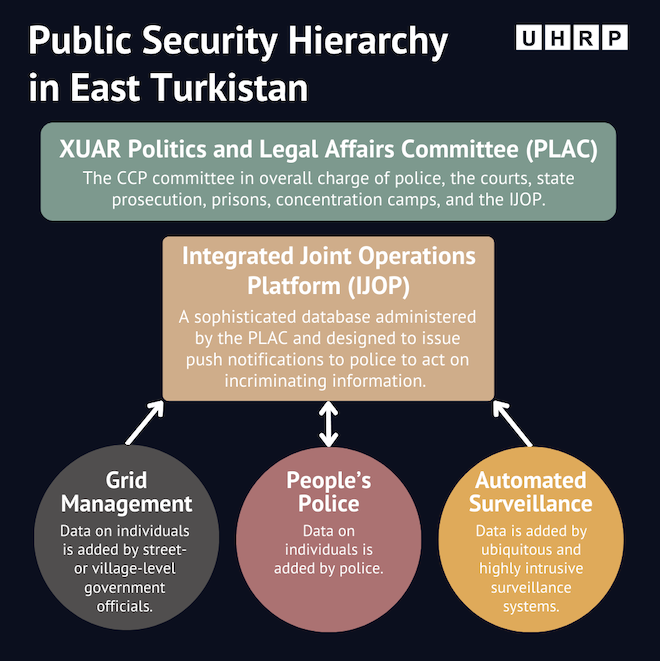

- XUAR Politics and Legal Affairs Committee (PLAC; Ch. 新疆维吾尔自治区政法委员会, Xinjiang weiwuer zizhiqu zhengfa weiyuanhui): the provincial-level version of the Central Politics and Legal Affairs Commission, common to all provincial-level administrations in the PRC; and a scion of the committee occupies a prominent position within each level of the administrative hierarchy down to the county level. In East Turkistan, in addition to overseeing the work of the police, the courts, state prosecution and prisons, the PLAC also directs the work of the various government agencies running the “Vocational Training and Education Centers” (more commonly known as the internment camps or concentration camps) via a subordinate CCP committee, the Counter-Terrorism and Stability Maintenance Command (Ch. 反恐维稳指挥部, Fankong weiwen zhihui bu).5See: Vicky Xiuzhong Xu, James Leibold and Daria Impiombato, “The architecture of repression: unpacking Xinjiang’s governance,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, October 19, 2021, online. Wang Mingshan, Party Secretary of the XUAR Politics and Legal Affairs Committee, was sanctioned by the U.S. Department of the Treasury in July 2020 under the terms of the Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act. See: “Treasury Sanctions Chinese Entity and Officials Pursuant to Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 9, 2020, online.

- Central Military Commission of the Communist Party of China (CMC; Ch. 中国共产党中央军事委员会, Zhongguo gongchan dang zhongyang junshi weiyuanhui): the CCP entity chaired by Xi Jinping which has sole control over the People’s Armed Police (see below), as well as China’s armed forces, the People’s Liberation Army (see above).

Government

- Ministry of Public Security (MPS; Ch. 公安部, Gongan bu): the central ministry with general administrative authority over the People’s Police (see below). The ministry has its own internal CCP structures, but is directed and supervised by the CPLAC (see above). The Minister for Public Security is typically also Deputy Party Secretary of the CPLAC.6

- XUAR Public Security Department (PSD; Ch. 公安厅, Gongan ting): the provincial-level branch of the MPS which administers the People’s Police (see below) in East Turkistan. Typically, the Director of the XUAR PSD is also the PSD’s Party Secretary, in addition to being appointed a Vice Governor (a government position).

- Public Security Bureau (PSB; Ch. 公安局, Gongan ju): the prefecture-level and county-level policing administrations, which run local county-, township-, and village-level police stations, under the direction and supervision of the PLAC (see above).

- Ministry of State Security (MSS; Ch. 国家安全部, Guojia anquan bu): the central ministry in charge of domestic and international intelligence, under the direction and supervision of the Central PLAC.

- XUAR Department of State Security (DSS; Ch. 新疆维吾尔自治区国家安全厅, Xinjiang weiwuer zizhiqu guojia anquan ting): the provincial-level branch of the Ministry of State Security, under the direction and supervision of the XUAR PLAC.

- Vocational Skills and Education Centers (Ch. 职业技能教育培训中心, Zhiye jineng jiaoyu peixin zhongxin): the official name of the institutions more commonly known by observers as “concentration camps” or “detention centers,” etc. The camps are run by a county-level government agency, the Vocational Skills and Education Services Management Bureau (Ch. 职业技能教育培训服务管理局, Zhiye jineng jiaoyu peixin fuwu guanli ju), with support from various other local government offices, including the Education Bureau, Health Bureau, Social Security Bureau, and the Public Security Bureau.7“Authorized to ‘Wash Clean the Brains’ — Agencies at Play Amid Mass Detention of Millions in the Uyghur Region,” Uyghur Rights Monitor, August 2, 2023, online. CCP control of the camps is exerted via the Counter-Terrorism and Stability Maintenance Command (Ch. 反恐维稳指挥部, Fankong weiwen zhihui bu), which is a sub-committee of the local county-level Politics and Legal Affairs Committees.

Legislature

- National People’s Congress (Ch. 全国人民代表大会, Quanguo renmin daibiao dahui): China’s rubber-stamp legislature which drafts and passes laws defining the work of the police.

- XUAR People’s Congress (Ch. 新疆维吾尔自治区人民代表大会, Xinjiang weiwuer zizhiqu renmin daibiao dahui): the regional body that adapts nationally-passed legislation for local contexts.

Other Forms of Policing: People’s Liberation Army

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA; Ch. 人民解放军, Renmin jiefang jun) is not publicly known to have been deployed during civil unrest in the PRC since the Tiananmen Massacre of June 4, 1989. On occasions since the Tiananmen Massacre, such as Tibet in 2008 and East Turkistan in 2009, active People’s Armed Police troops in militarised uniforms and using military hardware have apparently been mistaken by some eyewitnesses and in some reporting as “the army” or “the military” (see police uniforms below).

Even though the PLA may not have been active in Tibet and East Turkistan, the PLA and the People’s Militia (Ch. 中国民兵, Zhongguo minbing), its large auxiliary and reserve force, are nevertheless constituted to assist in “maintaining public order” when required and may therefore again be deployed against PRC citizens.8“Law of the People’s Republic of China on National Defence,” National People’s Congress, promulgated on March 14, 1997, online.

Other Forms of Policing: Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps

The Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC) has its own police, as well as courts, prosecution and prisons, the structures of which essentially mirror those in the rest in East Turkistan;9For a fuller overview of the XPCC, see: Greg Fay, “The Bingtuan: China’s Paramilitary Colonizing Force in East Turkestan,” UHRP, April 26, 2018, online. although, the XPCC’s nomenclature is similar to the PLA’s, reflecting the XPCC’s origins as an offshoot of the military.

The XPCC is a key actor in the genocide: it not only facilitates and profits greatly from forced labor and prison labor, but it also provides land and other resources for the regional government’s internment camps and prisons.10See: “Authorized to ‘Wash Clean the Brains’ — Agencies at Play Amid Mass Detention of Millions in the Uyghur Region,” Uyghur Rights Monitor, August 2, 2023, online; and Laura T. Murphy, Nyrola Elimä, and David Tobin, “Until Nothing is Left,” Helena Kennedy Centre for International Justice at Sheffield Hallam University, July 2022, online.

A key feature of the XPCC is its paramilitary militia, made up of local and mostly Han residents who are ostensibly in East Turkistan as part of the XPCC to “develop” the region and fortify its numerous international borders “with a gun in one hand and a pickaxe in the other.”11“新疆生产建设兵团维稳戍边与促进民族团结 [Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps maintains border stability and promotes national unity],” www.bingtuannet.com, November 26, 2018, online. This militia has been deployed several times in support of PAP operations in non-XPCC-administered areas of East Turkistan, including Ürümchi in July 2009, and also in Ghulja during the Ghulja Massacre in 1997.12“For example, the [XPCC] responded to the ‘5.29’ incident in Yining in 1962, the ‘5.19’ incident in Ürümchi in 1989, the ‘Baren Township incident’ in Akto County in April 1990, the ‘2.5’ incident in Yili in 1997, and the ‘7.5’ incident in Ürümchi in 2009.” See: 王彪, 卢大林 [Wang Biao and Lu Dalin],“新疆生产建设兵团履行维稳戍边使命之探究 [Exploration of the XPCC’s Fulfillment of the Mission of Maintaining Stability and Guarding the Frontier],” 法制博览 [Legality Vision], December 2018: 77–78.

III. Types of Police Forces Active in East Turkistan

People’s Armed Police

The illustration on the left is of a People’s Armed Police officer in full “Special combat uniform” (Ch. 特战服, Tezhan fu) alongside an illustration of a PLA infantry soldier in full battle dress (right). In direct comparison, there is an obvious difference in the color of the uniforms, but seen in isolation, the PAP officer could easily be mistaken for an infantryman in the military. PAP officers also have at least one other uniform that is much less militarized, which includes a short-sleeved olive-green shirt and shoes as opposed to boots.

The People’s Armed Police (PAP) (Ch. 人民武装警察部队, Renmin wuzhuang jingcha budui; also rendered as “The People’s Armed Police Force” in some sources) is a paramilitary police force constituted to “take necessary measures” for handling “riots, disruptions, serious violent crimes, terrorist attacks and other emergencies”13“Top legislature passes armed police law,” Xinhua, August 27, 2009, online. throughout all of the PRC. The PAP is a separate entity from the People’s Police (see below), and technically separate from the People’s Liberation Army (see above), but under the same commanding body as the military.

Sometimes described as “the paramilitary wing of the CCP,”14See for example, Joel Wuthnow, “China’s Other Army: The People’s Armed Police in an Era of Reform,” Institute for National Strategic Studies, April 2019, online. Chinese leader Xi Jinping has stated that the PAP “plays an important role in maintaining political security, especially regime security and system security.”15“中央军委向武警部队授旗仪式在北京举行 习近平向武警部队授旗并致训词 [Central Military Commission flag presentation ceremony to the People’s Armed Police held in Beijing, Xi Jinping presents flag to the People’s Armed Police and delivers speech,]” Xinhua, January 10, 2018, online.

In East Turkistan, PAP troops conduct routine foot patrols and maintain checkpoints while also on standby to put down incidents of civil unrest. During the Ghulja Massacre in February 1997 for example, PAP officers were responsible for opening fire on peaceful protestors, killing up to 100 people.16“UHRP Commemorates 25th Anniversary of Live-Fire Killings of Peaceful Uyghur Protesters in Ghulja,” Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP), February 4, 2022, online.

PAP officers are a conspicuous if normal sight in Ürümchi and other parts of East Turkistan, especially at politically sensitive times, when they are seen in camouflage fatigues and equipped with various firearms and other military hardware befitting a combat-ready soldier. It can be reasonably speculated that live fire directed against Uyghur protestors during the July 5, 2009 unrest in Ürümchi would almost certainly have come from PAP troops, although members of the “Special Police” (a unit within the People’s Police, see below) also fired live rounds.17Amy Reger and Henryk Szadziewski, “Can Anyone Hear Us? Voices From The 2009 Unrest In Ürümchi,” July 1, 2010, UHRP, online. The ordinary People’s Police are not routinely armed.18Suzanne E. Scoggins, Policing China: Street-Level Cops in the Shadow of Protest, (Ithaca NY, Cornell University Press, 2021), 85.

It is not publicly known where the order to deploy PAP troops in Ürümchi on July 5, 2009 originated. Based on previous understandings of PAP operations, it is feasible that it could have come from a CCP official in either the XUAR government, the Ürümchi municipal government, the central Ministry of Public Security, the national or regional Politics and Legal Affairs Committee, or even the Central Military Commission in Beijing.

Indeed, one of the stated intentions of sweeping reforms to the People’s Armed Police, formalized on January 1, 2018, was to streamline the chain of command, including a key measure to place the PAP, a civilian police force, under the sole command of the Central Military Commission (CMC), which controls the People’s Liberation Army. Analysts now understand that local governments and their related CCP committees must request deployment of the PAP (aside from routine patrols, etc.) in the event of civil unrest or disaster response, although the protocols for the CMC to respond to such requests are not publicly known.19Joel Wuthnow, “China’s Other Army: The People’s Armed Police in an Era of Reform,” Institute for National Strategic Studies, April 2019, online.

The key outcome of this measure is that local governments can no longer unilaterally mobilize the PAP, a move to prevent local governments using the PAP to abet corruption, as well as to curtail instances of heavy-handed deployment of PAP troops.

Notably, placing the PAP under the Central Military Commission’s sole command also grants Chinese leader Xi Jinping “direct control over all of China’s primary instruments of coercive power.”20Ibid.

Another key feature of the 2018 reforms was to remove several branches of the PAP to other areas of government, such as transferring the PAP Gold Corps (Ch. 部队, Budui, also rendered as “force” in some sources), which is tasked with protecting gold deposits and mines, to the Ministry of Natural Resources, for example. The intention of paring away these units was to concentrate the PAP into its core paramilitary fighting role.21Ibid.

The PAP’s “Internal Security Corps” (ISC; Ch. 内卫部队, neiwei budui, also rendered as “Internal Guard Force” in some sources) is the corps deployed during incidents of civil unrest. The ISC is comprised of a “Provincial Contingent” within each provincial-level administration of the PRC, including East Turkistan; and each Provincial Contingent is comprised of one or more “Mobile Detachments,” similar to an army regiment in terms of organizational and command structures.

The Chinese authorities evidently place high value on the presence and role of PAP forces in East Turkistan. First, East Turkistan has by far the most PAP Mobile Detachments of all provincial administrations, with at least seven – three based in Ürümchi (population approximately four million), two in Kashgar, and one in each of Ghulja and Hotan, compared to one in most provinces and only four in Beijing (population approximately 21 million).22Generally, western provinces with a large non-Han population have more Mobile Detachments than those in China’s interior. For example, at least 13 Mobile Detachments are based on or around the Tibetan plateau in the Tibet Autonomous Region, Qinghai, Sichuan, Gansu and Yunnan provinces.

Second, East Turkistan is unique in that the Xinjiang Production Construction and Corps’23The XPCC is a state-owned industrial and agricultural enterprise run in parallel to the provincial government in East Turkistan, constituted and administered on a paramilitary basis. See: Greg Fay, “The Bingtuan: China’s Paramilitary Colonizing Force in East Turkestan,” UHRP, April 26, 2018, online. (XPCC) own PAP forces were upgraded from the level of Mobile Detachment to Provincial Contingent in the 2018 reforms, meaning that East Turkistan is the only provincial-level administration in the PRC with two Provincial Contingents.24Joel Wuthnow, “China’s Other Army: The People’s Armed Police in an Era of Reform,” Institute for National Strategic Studies, April 2019, online.

Third, the East Turkistan PAP Provincial Contingent is at the same level of operational command as Beijing’s Contingent in the PAP’s command structure, an order of priority one grade higher than all other provincial-level administrations.25Vicky Xiuzhong Xu, James Leibold and Daria Impiombato, “The architecture of repression: unpacking Xinjiang’s governance,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, October 19, 2021, online. Fourth, within the PAP are three elite anti-terror commando units of “Special Police” (Ch. 特警, Tejing), which is not the same “Special Police” corps as that within the People’s Police (see below). One of these three PAP Special Police units, the “Mountain Eagle Commando,” is based in East Turkistan; the others being the Falcon Commando in Beijing, and the Snow Leopard Commando in Guangzhou.26“China’s Ministry of Public Security Issues a Three-Year Action Plan to Bring Xinjiang-style ‘One Police Station to Every Rural Village or Urban Grid Block’ Nationwide by the End of 2025,” ChinaChange, April 3, 2023, online.

In addition to the PAP forces physically based in East Turkistan, two PAP “Mobile Contingents” based in mainland China can also provide specialized capabilities when called upon, including special operations forces and a helicopter detachment.27Joel Wuthnow, “China’s Other Army: The People’s Armed Police in an Era of Reform,” Institute for National Strategic Studies, April 2019, online.

Finally, PAP troops from other Provincial Contingents in mainland China can be deployed to East Turkistan. In the wake of the July 5, 2009 unrest, an estimated 30,00028Adrian Zenz and James Liebold, “Securitizing Xinjiang: Police Recruitment, Informal Policing and Ethnic Minority Co-optation,” The China Quarterly, 242 (2020): 324–348, accessed September 27, 2023, online. PAP troops were drafted into various parts of East Turkistan from Henan, Jiangsu and Fujian provinces.29Yitzhak Shichor, “Handling China’s Internal Security: Division of Labor among Armed Forces in Xinjiang,” Journal of Contemporary China, 28, no. 119 (2019): 813–830, accessed September 27, 2023, online.

It is not known how many PAP troops are permanently based in East Turkistan, but one analysis estimated there were 200,000 PAP troops in East Turkistan in 2017.30Adrian Zenz and James Liebold, “Securitizing Xinjiang: Police Recruitment, Informal Policing and Ethnic Minority Co-optation,” The China Quarterly, 242 (2020): 324–348, accessed September 27, 2023, online. Another analysis suggests a Provincial Detachment comprises up to 30,000 troops,31“People’s Armed Police (PAP) Special Operations Forces,” Boot Camp & Military Fitness Institute, June 13, 2017, online. and with at least seven Provincial Detachments in East Turkistan, an estimate of 200,000 PAP troops in the region would appear feasible. Neither is it known how many PAP troops there are nationally: a single article in the official media in 2021 stated there were 1.2 million,32“武警、特警、特种部队有什么区别?分别执行什么样的任务 [What’s the difference between the PAP, the Special Police and Special Forces? How are their duties divided?],” www.163.com, February 23, 2021, online. which suggests that a sixth of the PAP’s entire troop count is based in East Turkistan, even though the region’s population is only 1.5 percent of the PRC’s population.

Other Forms of Policing: Chinese Communist Party

It is standard practice throughout the PRC for all policing agencies (indeed, any office with executive authority) to be under the strict control of the CCP. While the bureaucracy of policing in China has been described by an analyst as fragmented, it is nevertheless “also highly centralized through the [CCP] hierarchy.”33Adrian Zenz and James Liebold, “Securitizing Xinjiang: Police Recruitment, Informal Policing and Ethnic Minority Co-optation,” The China Quarterly, 242 (2020): 324–348, accessed September 27, 2023, online.

Typically, any police officer with any seniority will also be the Party Secretary (Ch. 书记, Shuji) of the CCP committee installed within that same office. So, for example, the Minister for Public Security, currently Wang Xiaohong, is also the ministry’s Party Secretary (although he is junior to the Party Secretary of the Central Politics and Legal Affairs Commission – see above). Similarly, the Director (Ch. 主任, Zhuren) of a county-level Public Security Bureau (PSB) is also likely to be the Party Secretary of that same county’s PSB Party Committee.

This principle also applies to prisons, the judiciary and the state prosecution, where judges and prosecutors are likely to be members if not secretaries of their own office’s CCP committees.34Uniquely, the XUAR State Prosecution appoints two separate people to the positions of Director and Party Secretary. See: “新疆国家安全厅厅

长,已赴这里履新 [Director of Xinjiang Department of State Security leaves to take up new post],” www.sina.com, December 17, 2021, online. However, these positions are still junior to those on the parallel Politics and Legal Affairs Committees. The CCP dismisses the notion of judicial independence as a “Western erroneous view.”35“China releases key guideline on legal education, stresses firm stand to oppose Western erroneous views,” Global Times, February 27, 2023, online.

Other Forms of Policing: Government Administrative Offices

Government administrative offices are involved in policing and security work in East Turkistan to a degree not seen elsewhere in the PRC. Zhang Chunxian, Party Secretary of the XUAR from 2010 to 2016, insisted “There is no department that doesn’t have something to do with stability,” and indeed, according to a 2021 study, there are 170 CCP and government entities in East Turkistan and Beijing directly or indirectly engaged in the genocide.

These include such unlikely entities as the Forestry Bureau (which for a period ran a concentration camp in Kashgar), but also offices such as county-level Education Bureaus, which run “re-education” in the camps, and Human Resources and Social Security Bureaus, which administer people’s release from the internment camps and their entry into forced labor programs.36Vicky Xiuzhong Xu, James Leibold and Daria Impiombato, “The architecture of repression: unpacking Xinjiang’s governance,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, October 19, 2021, online.

In addition, senior police officers are appointed to positions in East Turkistan such as deputy principals of schools and to executive positions on grassroots governance bodies, a practice which has not been noted elsewhere in the PRC.37“China’s Ministry of Public Security Issues a Three-Year Action Plan to Bring Xinjiang-style ‘One Police Station to Every Rural Village or Urban Grid Block’ Nationwide by the End of 2025,” ChinaChange, April 3, 2023, online.

People’s Police

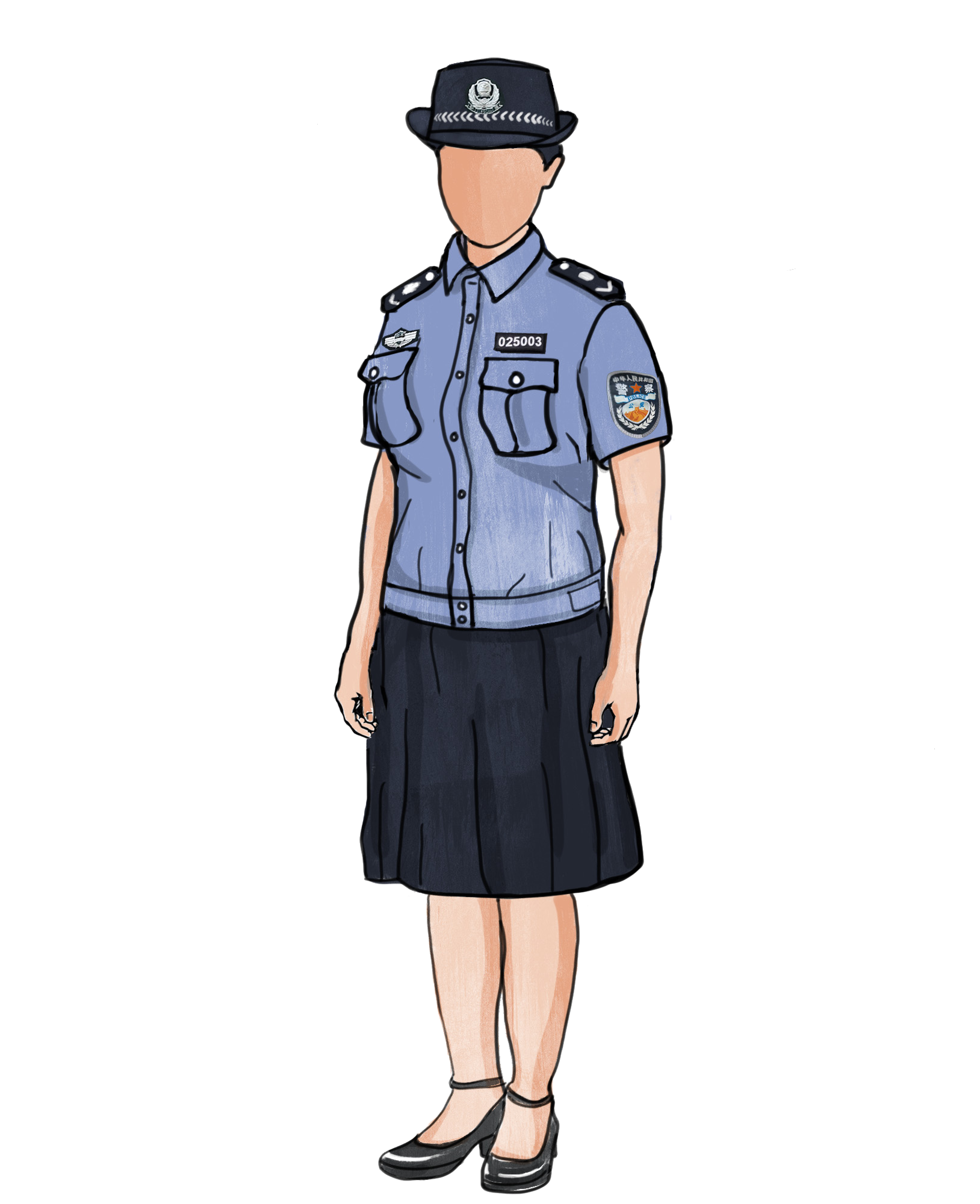

The figure on the left is a People’s Police Patrol officer in full “Fall and spring uniform” (Ch. 春秋 常服, Chunqiu changfu) alongside an officer in the same uniform but without the jacket, and showing a blue shirt. This shade of blue commonly identifies the People’s Police throughout the PRC, and it generally features in most of the different People’s Police corps’ variations of uniform. However, some senior officers wear white shirts; in other corps, white caps are standard.

The People’s Police (Ch. 人民警察, Renmin jingcha) is the largest and most prevalent police force in the PRC, and generally what’s meant when people refer to “the police.”

The basic structure of the People’s Police in East Turkistan appears to be the same as in other provincial administrations of the PRC: at the provincial level, the Public Security Department (PSD; Ch. 公安厅, Gongan ting) administers the prefecture- and county-level Public Security Bureaus (PSB; Ch. 公安局, Gongan ju), and the PSBs in turn run various forms of police station down to the village level, including the numerous “convenience police stations” (Ch. 便民警务站 Bianmin jingwu zhan) – a relatively recent innovation to position police surveillance and dispatch points in multiple locations throughout urban and rural communities. The PSD is mostly administrative, and public interaction with People’s Police officers generally takes place at the county level and below.

There are various “corps” (Ch. 总队, Zongdui) in the People’s Police, each with a specific remit. The officers most commonly seen throughout East Turkistan and the PRC generally are the Patrol Police (Ch. 巡逻警察, Xunluo jingcha), while other more specialized corps include the Criminal Investigation Corps, the Traffic Police Corps, and the Anti-Narcotics Corps. The People’s Police is also responsible for administering ID cards and household registration (Ch. 户口, Hukou) via the Security Management Corps (Ch. 治安管理总队, Zhian guanli zongdui), and issuing, or denying and confiscating passports38See: Henryk Szadziewski, “Weaponized Passports: The Crisis of Uyghur Statelessness,” UHRP, April 1, 2020, online. via the Entry and Exit Management Bureau (Ch. 出入境管理局, Churu jing guanli ju).39“公安厅机关基本信息 [Basic information on the Public Security Department],” Xinjiang Public Security Department, April 23, 2023, online.

According to UHRP’s sources, officers in the Security Management Corps have been instrumental in gathering information on Uyghurs in East Turkistan whose family members have escaped into exile, and then using that information to threaten and intimidate those in exile – an element of transnational repression.40To see UHRP’s extensive writing on transnational repression, go to “Transnational Repression Resources” at: online. The hundreds of Chinese “overseas police stations” around the world are reportedly run by the People’s Police from various provincial Public Security Departments, but Ministry of State Security (see below) personnel are also known to conduct transnational repression from these offices.41See for example: Martin Purbrick, “The Long Arm of the Law(less): The PRC’s Overseas Police Stations,” The Jamestown Foundation, June 12, 2023, online; and: Martin Pubrick, “Future Global Policeman? The Growing Extraterritorial Reach of PRC Law Enforcement,” The Jamestown Foundation, May 13, 2022, online.

People’s Police officers, including Assistant Police (see below), are also instrumental in manually adding data to the Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP), a large and sophisticated database maintained by the Political and Legal Affairs Committee (see above) as opposed to the People’s Police themselves. Data on individuals is also added by neighborhood-level government administrative staff, including those in the “grid management” system of micro-managing small groups of households within a community. Grid management staff, who are usually local volunteer residents from within their own group of 10 or so households, are empowered to visit and search people’s homes essentially at will, and the information they gather on, for example, people’s religiosity – eating, drinking and smoking habits, whether they pray, their foreign connections – is recorded and entered into the IJOP using a dedicated smartphone app.42“China’s Algorithms of Repression,” Human Rights Watch, May 1, 2019, online.

The IJOP forms the pinnacle of a vast surveillance infrastructure in East Turkistan. In addition to manually added data, a large amount is added automatically: the ubiquitous and highly sophisticated facial recognition camera network in the region43See: Nuzigum Setiwaldi, “Hikvision’s Links to Human Rights Abuses in East Turkistan,” and “Dahua’s Links to Human Rights Abuses in East Turkistan” UHRP, October 17, 2023, online. can seamlessly record an individual’s physical presence through public44Dahlia Peterson, “How China harnesses data fusion to make sense of surveillance data,” Brookings Institute, September 23, 2021, online. and even private spaces;45Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian, “Report: Hikvision cameras help Xinjiang police ensnare Uyghurs,” Axios, June 14, 2022, online. it records individuals’ “virtual identity,” including their Internet, phone and app usage,46Dahlia Peterson, “How China harnesses data fusion to make sense of surveillance data,” Brookings Institute, September 23, 2021, online. and even records people’s gas and electricity consumption as well as their package deliveries.47“China’s Algorithms of Repression,” Human Rights Watch, May 1, 2019, online.

One of the IJOP’s primary functions is to enable “predictive policing” by using Artificial Intelligence to generate push notifications for police to investigate individuals based on information processed and deemed incriminating by the IJOP.48Vicky Xiuzhong Xu, James Leibold and Daria Impiombato, “The architecture of repression: Unpacking Xinjiang’s governance,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, October 19, 2012, online. People’s Police officers can then detain individuals based on IJOP push notifications.

Once an individual has been detained, he or she may be sent to an internment camp by means of an administrative process (as opposed to a judicial process) under the direction of the local Politics and Legal Affairs Committee without formal charge, legal representation or judicial oversight;49“Authorized to ‘Wash Clean the Brains’ — Agencies at Play Amid Mass Detention of Millions in the Uyghur Region,” Uyghur Rights Monitor, August 2, 2023, online. or, the individual may be charged with a statutory crime and formally arrested, whereupon legal representation and judicial oversight are ostensibly available. In these cases, conviction is basically inevitable – the conviction rate for criminal cases tried in court throughout all of the PRC is “above 99.9 percent.”50“Xinjiang Official Figures Reveal Higher Prisoner Count,” Human Rights Watch, September 14, 2022, online.

Policing throughout all of the PRC, but possibly mostly so in East Turkistan, is largely an exercise in “maintaining stability” (Ch. 维稳, weiwen), which is arguably a political goal set by the CCP as opposed to a policing strategy.51For an archive of articles and analysis about the Chengguan, see: “Chengguan,” China Digital Times, accessed on June 21, 2023, online.

According to a recent in-depth study, the MPS’ focus on maintaining stability – being quick to quash public protest or any form of dissent or divergence from the Party-state’s expectations – is “highly centralized and robust in terms of capacity, but control over many other types of crime is decentralized and weak.” For example, a general operating scenario is that traffic police officers are likely to be the first to come across a public protest: they are trained to immediately clear the streets, and if the protest turns violent or is thought likely to become violent, the PAP is called in.52Suzanne E. Scoggins, Policing China: Street-Level Cops in the Shadow of Protest, (Ithaca NY, Cornell University Press, 2021), 87. This seemingly straightforward protocol actually involves the integration of two entirely separate chains of command across numerous administrative and command ranks: a street-level traffic police officer’s report of an incident is conveyed by the PSB all the way up to the PAP’s command, the CMC in Beijing (or possibly a regional proxy in East Turkistan), and the response is then relayed back down and across the various different ranks and command channels.

In contrast, in the case of drug crime for example, in one instance there are reportedly no regularized communication protocols between border defense forces (formerly a PAP corps, now also under the CMC) and police in nearby cities to warn them of a potential influx of narcotics.53Ibid., 102.

A consequence of the more fragmented protocols for common crime is that “outcomes for the majority of crimes that local police have to deal with on a daily basis are not good.”54Ibid., 109. In other words, the People’s Police are more institutionally adept at tackling perceived affronts to the CCP’s authority than they are at tackling crime.

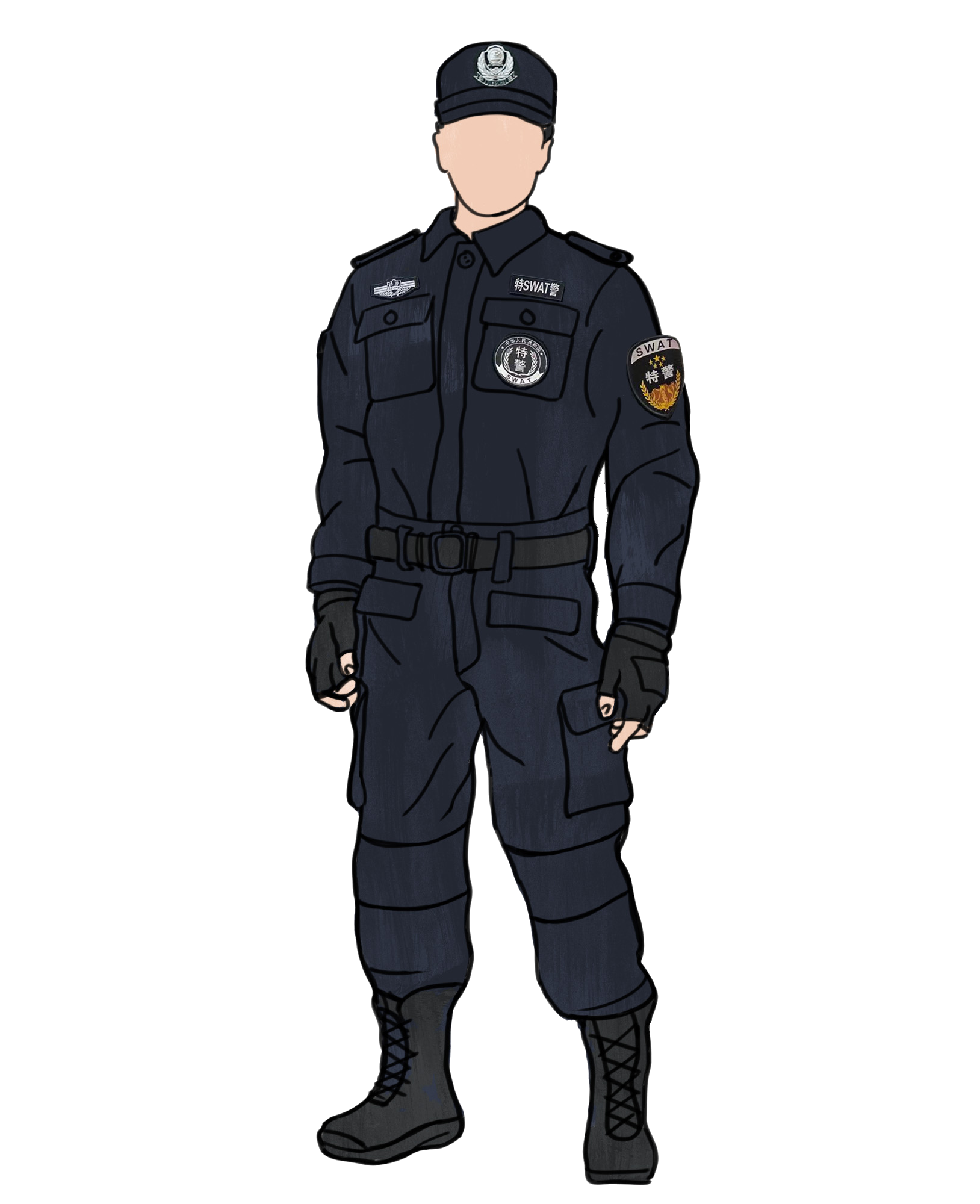

Special Police

On routine patrols or when on sentry duties at key locations, Special Police officers are readily identifiable by their black uniforms. Featuring high baseball-style caps, combat boots and often mirrored aviator shades, presenting a highly stylized and aggressive impression. In full paramilitary gear worn for riot control, bearing powerful firearms or long night sticks, the Special Police are particularly intimidating.

The Special Police (Ch. 特警, Tejing) is a strategic weapons and tactics (SWAT) corps within the People’s Police and under the command of the provincial-level Public Security Departments, with officers stationed at the prefectural and county levels.

According to one analysis, the Special Police has four primary roles: street-level patrols, where a number of officers stand on sentry duty in a key position, and their presence – in all-black fatigues and bearing firearms or long night clubs – is essentially a deterrent; crisis interventions, such as rescuing victims in a hostage situation or preventing a suicide; dangerous searches and arrests in support of operations by other branches of the People’s Police such as the Criminal Investigation Corps or Anti-Narcotics Corps; and crowd control.55Lu Liu, “Special tactical police’ experience and perception of their use of force: Evidence from the Chinese SWAT police,” Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, October 5, 2022, online.

It is not publicly known how the Special Police’s crowd control duties overlap with those of the PAP. During the Ürümchi Unrest of July 5, 2009, Special Police officers were reported by witnesses as opening fire with live rounds into crowds as well as heavily beating protestors.56Ibid., 109. According to a 2017 report, Special Police officers can be issued with any one of six types of firearm, including a sniper rifle, a shotgun described as “powerful and extremely intimidating,” and a submachine gun57“盘点中国特警常用的六大枪械 女特警常配备这款武器[Check out the six major firearms commonly used by Chinese special police – female special police are often equipped with these weapons”], www.sina.com, March 20, 2017, online. capable of firing 15 rounds per second.58A QCW 05 submachine gun. See: QCW-05, Wikipedia, undated, online. In the wake of the unrest, Special Police officers were drafted into Ürümchi from cities across the PRC to conduct patrols and run checkpoints around the city.59Amy Reger and Henryk Szadziewski, “Can Anyone Hear Us? Voices From The 2009 Unrest In Ürümchi,” July 1, 2010, UHRP, online.

Information in the leaked “Xinjiang Police Files” shows that in at least one county in East Turkistan, the Special Police perform guard duties at concentration camps, staffing watchtowers and forming part of “Strike Groups” within the concentration camps, tasked with “arresting and removing” unruly inmates.60“Shufu County Public Security Bureau Re-Education Center Police Brigade New Vocational Training Center Police Station Division of Responsibilities and Tasks,” Xinjiang Police Files, accessed June 18, 2023, online.

Special Police officers were also dispatched to Thailand in 2015 to escort 109 Uyghur refugees who were being deported to the PRC by Thai authorities. In an image in China’s official media taken on one of the two planes sent to take the Uyghur refugees back, some of the refugees are visible wearing numbered bibs and black hoods over their heads, each sitting between two uniformed Special Police officers.61Jonathan Head, “Aziz Abdullah: Uyghur asylum-seeker death heaps pressure on Thailand,” BBC, February 20, 2023, online; see also: Ben Carrdus, “‘I Escaped, But Not to Freedom’: Failure to Protect Uyghur Refugees,” UHRP, June 20, 2023, online. The precise nature of the diplomatic mechanism which permitted Chinese police officers to operate in Thailand is not known; however, the Ministry of Public Security has brokered bilateral agreements on policing with numerous other countries.62See: Jordan Link, “The Expanding International Reach of China’s Police,” The Center for American Progress, October 17, 2022, online.

Assistant Police

The Assistant Police63All information in this section, unless otherwise footnoted, is from: Adrian Zenz and James Liebold, “Securitizing Xinjiang: Police Recruitment, Informal Policing and Ethnic Minority Co-optation,” The China Quarterly, 242 (2020): 324–348, accessed September 27, 2023, online. (Ch. 协警 or 辅警 Xiejing or Fujing) is a large contingent of low-skilled “foot soldiers” within the People’s Police throughout the PRC. Assistant Police are typically hired on short-term contracts without the cost or commitment of formally trained police officers, making them a relatively easy way to boost community policing and surveillance.

In East Turkistan, there appears to be exceptionally high numbers of Assistant Police, complementing the People’s Police numbers that are already more than twice as high as the national average (see above). One analysis from 2017 showed that on a per capita basis, East Turkistan attempted to recruit over 40 times more Assistant Police officers than Fujian or Guangdong provinces did, and over 90 times more than Zhejiang province did. In real terms, this translated to almost 70,000 Assistant Police in 2017. The same analysis noted that 86% of these positions were for staffing “police convenience stations,” a form of police station first seen in Tibet and then introduced throughout East Turkistan in 2016, staffed by between six and 30 officers, including a complement of Assistant Police.

Assistant Police are primarily tasked with staffing these convenience police stations, conducting foot patrols and checking IDs. They do not have any enforcement rights such as the power to conduct an arrest. However, they are also described as playing an intimidatory role; their uniforms and insignia are very similar to those of the ordinary People’s Police (see Police Uniforms below). Elsewhere in the PRC, Assistant Police are also known to be typically tasked with monitoring political dissidents.64For an archive of articles and analysis about the Chengguan, see: “Chengguan,” China Digital Times, accessed on June 21, 2023, online.

Assistant Police positions in East Turkistan are well-paid, and the positions do not require specialized qualifications or educational requirements. Assistant Police positions therefore represent a rare career opportunity for Uyghurs and other Turkic people in East Turkistan, who otherwise have extremely limited options in the Chinese-dominated public and private employment spheres.

Nevertheless, the job is considered highly stressful: Uyghur recruitment is used by the party-state as a means of “getting ethnic groups to police their own people,” which has the potential to place Uyghur officers in contentious situations; a significant proportion of the pay and benefits, while unusually good, are often performance-dependent and liable to be withheld if targets are not met; and there are accounts of Uyghur officers being threatened with internment in a concentration camp if they attempt to resign.

Other Forms of Policing: Ministry of State Security

While the People’s Police undoubtedly has its own means of gathering intelligence, the Department of State Security in East Turkistan – the provincial-level branch of the central Ministry of State Security – is specifically tasked with intelligence gathering. Very little is publicly known about the DSS in East Turkistan; UHRP was unable to even find the name of the current DSS Director in public sources,65A report in China’s state media notes that a previous incumbent, Tian Yong, was transferred out of the position of Director and Party Secretary of the DSS in December 2021 and appointed Party Secretary of the XUAR State Prosecution. No details of his replacement at the DSS are provided in the report. See: “新疆国家安全厅厅长,已赴这里履新 [Director of Xinjiang Department of State Security leaves to take up new post],” www.sina.com, December 17, 2021, online. nor how it operates alongside the Ministry of Public Security at the central level or the People’s Police at the local level.

MSS personnel are reported to operate out of at least some of the Chinese “overseas police stations” around the world, targeting exiled and refugee Uyghurs; in 2015, information leaked that the MSS was hiring people with “minority language” skills,66Peter Mattis, “Everything We Know about China’s Secretive State Security Bureau,” The National Interest, July 19, 2017, online. and while it is known that there is a Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau Bureau among the “at least 18” bureaus within the central ministry,67Peter Mattis and Matthew Brazil, Chinese Communist Espionage: An Intelligence Primer, Annapolis MD, Naval Institute Press, 2019, 32–33. it is therefore likely that at least one bureau has a direct or indirect brief on East Turkistan.

Other Forms of Policing: Chengguan

The Urban Administrative and Law Enforcement Bureau (Ch. 城市管理行政执法局, Chengshi guanli xingzheng zhifa ju), commonly shortened to Chengguan (Ch. 城管), is not a policing agency in that it is not under the control of the Ministry of Public Security, and Chengguan officers do not have any powers of arrest. Throughout cities across all of the PRC however, uniformed Chengguan officers are tasked with enforcing bylaws, such as ensuring street vendors are licensed, and monitoring work safety and pollution, etc. Chengguan officers have a reputation throughout all of the PRC for corruption and thuggery.68For an archive of articles and analysis about the Chengguan, see: “Chengguan,” China Digital Times, accessed on June 21, 2023, online.

UHRP is not aware of any reports to indicate Chengguan officers play a coercive role specifically targeting Uyghurs in East Turkistan’s cities. On the contrary, one account from 2016 claims Chengguan officers in Ürümchi are “afraid of Xinjiang people” who are “united and fierce,” and instead Chengguan officers “only bully us kind [Han Chinese] people.”69“为什么城管不敢追新疆人,原来是这样? [Why don’t the Chengguan go after Xinjiang people – has it always been this way?]” TMC淘米菜 (blog posting), November 5, 2016, online.

VI. Appendix

It can be difficult to distinguish between officers in the various branches of China’s police forces by their uniforms. Similarities exist not only between general appearances (including similarities to PLA soldiers), but within a single force – the People’s Armed Police, for example – there are different corps, and each corps has its own variations of uniform and insignia, along with further differences depending on duties (riot control or disaster response) and occasions (training or ceremonial uniforms), and each will generally have other variations depending on the weather and the season.

Each branch of the police has its own emblems and other insignia identifying the corps, along with other features – symbols and stripes – denoting unit and officer rank or grade. The details, however, are not obvious: the color of an epaulet or the style of button can sometimes be the only distinguishing feature between officers in different corps.

The following descriptions provide an outline guide to the uniforms worn by the different police described in this explainer, but makes no attempt nor claim to be a comprehensive guide.

People’s Armed Police

The figure on the left is of a PAP officer in full “Special combat uniform” (Ch. 特战服, Tezhan fu) alongside a figure of a PLA infantry soldier in full battle dress (right). In direct comparison, there is an obvious difference in the color of the uniforms, but seen in isolation, the PAP officer could easily be mistaken for an infantryman in the military. PAP officers also have at least one other uniform that is much less militarized, which includes a short-sleeved olive-green shirt and shoes as opposed to boots.70Five different PAP uniforms are shown in this short video on the PAP’s YouTube channel: “武警”八音盒“变装来啦!你最喜欢哪套呢? [The PAP uniform changing music box is here! Which is your favorite?],” PAP中国人民武警 [PAP China People’s Armed Police], July 27, 2023, online.

People’s Police

The figure on the left is a People’s Police Patrol officer in full “Fall and spring uniform” (Ch. 春秋常服, Chunqiu changfu) alongside an officer in the same uniform but without the jacket, and showing a blue shirt. This shade of blue commonly identifies the People’s Police throughout the PRC, and it generally features in most of the different People’s Police corps’ variations of uniform (although some senior officers wear white shirts; in other corps, white caps are standard).

Special Police

On routine patrols or when on sentry duties at key locations, Special Police officers are readily identifiable by their black uniforms featuring high baseball-style caps, combat boots and often mirrored aviator shades, presenting a highly stylized and aggressive impression. In full paramilitary gear worn for riot control, bearing powerful firearms or long night sticks, the Special Police are particularly intimidating.

Chengguan

Chengguan officers’ uniforms vary from place to place. Although obviously styled on police uniforms, the shade of blue on the shirts is significantly darker than the distinctive pale blue in the People’s Police uniforms (see photo on p.7). Chengguan officers also have their own set of emblems and insignia, positioned in much the same places on their uniforms as the formal police.

Assistant Police

Assistant Police officers are almost indistinguishable from ordinary People’s Police. A description on the website of a company that manufactures police uniforms states, “Aside from differences in police rank and numbering, Assistant Police uniforms and People’s Police uniforms are basically the same.” The description then lists several minor distinguishing differences, such as the kind of buttons on epaulets and the formatting of the officers’ numbers.

However, as another guide to distinguishing between them, the description adds: “People’s Police officers stand tall and straight with sharp and steady eyes; but there are some Assistant Police who stand swaying from side to side, and their uniforms are dishevelled and their expressions are listless.”71“教你如何区分协警和正式警察服装 [How do you distinguish between an Assistant Police and a formal People’s Police uniform?]” Police Uniform Network, September 13, 2023, online.

Security Guards

Private security guards in the PRC commonly wear uniforms deliberately intended to resemble if not actually imitate police uniforms. There are numerous online articles discussing how to distinguish a security guard from a police officer, particularly in instances when the security guard is wearing a shirt that’s the same distinctive light blue of the People’s Police. As one scholar put it, “Sometimes it is almost impossible to know if someone is an official police officer without asking him or her directly,” and she relates the advice she once received from a serving police officer: “Look at their feet. Real officers wear police shoes.”72Suzanne E. Scoggins, Policing China: Street-Level Cops in the Shadow of Protest, (Ithaca NY, Cornell University Press, 2021), 27.

VI. About the Author

Policing East Turkistan was researched and written by Ben Carrdus, Senior Researcher at the Uyghur Human Rights Project.

VII. Acknowledgements

The author would like to express appreciation for the expert review and editing of Dr. Henryk Szadziewski, UHRP Director of Research; Peter Irwin, UHRP Associate Director for Research and Advocacy; Omer Kanat, Executive Director of UHRP, and Yalkun Uluyol at the Uyghur Rights Monitor. Any remaining errors and oversights are the fault of the author alone.

Cover art by YetteSu.

© 2023 Uyghur Human Rights Project. Please share materials freely, with appropriate attribution, under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

FEATURED VIDEO

Atrocities Against Women in East Turkistan: Uyghur Women and Religious Persecution

Watch UHRP's event marking International Women’s Day with a discussion highlighting ongoing atrocities against Uyghur and other Turkic women in East Turkistan.