A Uyghur Human Rights Project report by Dr. Rachel Harris and Abduweli Ayup. Read our press statement on the briefing, download the full briefing in English, and view a printable, one-page summary of the report.

Read coverage of the report in The Guardian, as well as additional coverage in RTL, Voice of America, The Asia Freedom Institute, Bitter Winter, and China Digital Times.

I. Key Takeaways

- This report provides detailed evidence that overturns the perception that criminal prosecutions and long prison sentences in the Uyghur Region have been mainly handed down against men.

- Uyghur women are denied freedom of religion and belief. Women’s religious learning and religious gatherings, daily prayer, and wearing the hijab have all been explicitly criminalized.

- State narratives about Uyghur women have consistently denied them agency. Their religious practice has historically been overlooked by the CCP since it was not tied to the mosque. Under the “anti-extremism” campaigns, women who acted as religious teachers and leaders in the community have been portrayed as the dupes of religious extremism.

- Many elderly women, some over the age of 80, have been detained and imprisoned for religious learning that took place 20 or 30 years previously, often when the accused was as young as five or six years old.

- Many sentences were made retrospectively, for “crimes,” such as studying the Quran or wearing a hijab, committed before the practice was deemed illegal.

- 91 women from a single county were detained because they were officially registered by the state as büwi (female religious leaders).

- The detention and imprisonment of female religious leaders and the criminalization of children’s religious socialization—in which women play a significant role—hastens the destruction of Uyghur communities.

- The denial of Uyghur women’s freedom of religion or belief should be understood in the context of other abuses of women’s rights including gender-based violence in detention, forced sterilization and abortion, and forced marriage.

II. Executive Summary

The mass incarceration of women who lead or engage in religious activities and learn or teach religious knowledge has struck at the heart of Uyghur communities, denying agency and free will to hundreds of thousands of women, disrupting the socialization of children and the transmission of culture, and disrupting the normal conduct of births, marriages and deaths.

This report draws on the extensive data contained in the “Xinjiang Police Files,”1The Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation provided the set of files analyzed in the current report to UHRP. supplemented by original interviews and other published reports, to document the internment and imprisonment of religious Uyghur women. We highlight the long prison sentences awarded to numerous women for the “crime” of learning a few verses of the Quran during their childhood: the basics needed to fulfill the fundamental Muslim duty of daily prayer. We note the detention of elderly women, the coerced return of Uyghur women from abroad, and the use of intrusive digital surveillance and forced confessions.

In order to contextualize these human rights abuses, we provide a brief historical overview of the relationship between Uyghur women, Islam, and the Chinese Communist Party (CPP). During the 20th century, Uyghur women’s religious practice was largely overlooked in official policy. We trace the shift in policy in 2009 which brought women’s religious affairs more directly under the control of the authorities. This attempt at oversight was quickly overturned by new policies: the wholesale criminalization of women’s religious practice and widespread police harassment of religious families. In 2017, this escalated to mass internment and imprisonment.

This report highlights the intersection between denial of religious freedoms and denial of women’s rights, and argues for the need to consider gender in order to fully understand crimes against humanity. The Chinese authorities claim to be liberating Uyghur women from the shackles of religious extremism and re-educating them for a better future, but the evidence unearthed by this report suggests instead a pattern of removing women from positions of religious and cultural leadership, and subjecting large numbers of women to long periods of imprisonment for their everyday religious practice.

III. Introduction

China’s official narrative around its campaigns in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (hereafter the Uyghur Region) has consistently highlighted religious faith and practice as a source of existential threat to national security.2The toponyms “Uyghur homeland” and “Uyghur Region” are used in this report, which along with “East Turkistan” are preferred by Uyghurs in the diaspora over “Xinjiang” and the “Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region,” which are seen as offensive colonial terms. In cases where we cite particular publications or refer to government offices and apparatuses, we do use “Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region” or related forms such as “the XUAR” or “Xinjiang.” China continues to claim that intrusive surveillance and mass detention are necessary to counter terrorism and eradicate Islamic extremism.

These claims have been thoroughly discredited.3“OHCHR Assessment of Human Rights Concerns in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China,” United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 31 August 2022, 5–11, online. We know now that the scope of the campaigns stretches far beyond the sphere of religion, encompassing attacks on Uyghur language, culture and history, family and community life. Those detained for “re-education” in the region’s internment camps and subsequently given long prison sentences include secular intellectuals, artists, “two-faced” officials,4The term “two-faced people” was used in 2017 to encourage a witch hunt against officials previously regarded as loyal, who might be revealed to harbor separatist or religious ideologies. See: Li Zaili, “Witch Hunt for ‘Two-Faced Persons’ in Xinjiang Universities,” Bitter Winter, July 25, 2019, online. and people who had traveled abroad or had relatives living abroad. Nonetheless, it is clear that the campaigns have particularly targeted religious faith and practice.5“Devastating Blows: Religious Repression of Uighurs in Xinjiang,” Human Rights Watch, April 11, 2005, online.

The criminalization of religious belief and practice attacks the customs and social networks which underpin traditional Uyghur community life.

The “signs of religious extremism” listed in the official documents that are used to send people to the internment camps include forms of everyday religious practice for millions of Muslims worldwide (reading the Quran, fasting, eating halal, modest dress, etc.). This wide-ranging criminalization of Islamic belief and practice appears to be underpinned by the assumption that Islam draws Uyghurs away from identification with China and submission to the rule of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). But this sweeping assault on religious belief and practice also fundamentally undermines Uyghur culture and identity. The criminalization of religious belief and practice attacks the customs and social networks which underpin traditional Uyghur community life. These include the life cycle rituals around birth, marriage and death, the annual cycle of fasting and festivals, the daily rhythms of prayer, and the socialization of children through basic religious instruction.

In all of these practices, women play crucial roles as religious teachers and as ritual specialists who lead women’s religious gatherings and conduct the necessary rituals for birth, marriage and death. As the data presented in this report makes clear, the socialization of Uyghur children through basic religious instruction has been a key target of the campaigns, with large numbers of women imprisoned for sentences of up to 20 years for the “crime” of learning to recite verses from the Quran when they were children, often many years previously.

The targeting of male religious leaders—imams who serve the community through their officially sanctioned role in the mosque—has been relatively straightforward to document, and UHRP has already produced a detailed report on the detention and imprisonment of imams.6Peter Irwin, “Islam Dispossessed: China’s Persecution of Uyghur Imams and Religious Figures,” Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP), May 13, 2021, online. The fate of female religious leaders has been less visible and harder to document, as they are not usually known beyond the local sphere and are not tied to any institutions. Nonetheless, their role in the community is crucial, and their mass incarceration is a major blow to Uyghur culture and society.

The separation between advocacy for the rights of women and advocacy for freedom of religion has meant that historically the intersections between gender and freedom of religion have been less emphasized in the human rights sphere.7Nazila Ghanea, “Piecing the Puzzle—Women and Freedom of Religion or Belief,” The Review of Faith & International Affairs, 20, no. 3 (2007): 4–18, DOI: online. Advocacy for the rights of women has often tended to view religion as a repressive force which restricts women’s agency, and there are, of course, numerous examples worldwide of states using religion as a rationale for restricting the rights of women. However, more recent voices in the human rights sphere have asserted that women’s rights and freedom of religion are not fundamentally clashing rights.

Professor of Human Rights Law, Nazila Ghanea, argues that we need to recognize the distinction between the freedom of religion or belief (FoRB) and “religion” per se. Freedom of religion as a human right does not protect religion as such, but aims at the empowerment of human beings, as individuals and communities. Ghanea argues that “it is essential to (re)vitalize the synergies between FoRB and women’s equality in order to advance each of these rights, to be able to address overlapping rights concerns, and to adequately acknowledge intersectional claims.”8Nazila Ghanea, “Women and Religious Freedom: Synergies and Opportunities,” United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, July 2017, online.

Our report builds on this understanding of the intersection of women’s rights and freedom of religion, to argue that the denial of the right to religious belief contributes to the denial of agency and removal of social capital for Uyghur women. This feeds directly into the dehumanization of Uyghur women which enables forms of violence against them including sexual violence, forced sterilization and forced marriage.

The denial of the right to religious belief contributes to the denial of agency and removal of social capital for Uyghur women. This feeds directly into the dehumanization of Uyghur women which enables forms of violence against them including sexual violence, forced sterilization and forced marriage.

The report brings together, for the first time, information from original interviews conducted with Uyghur exiles in Turkey, and leaked data from police records, to paint a picture of the persecution of Uyghur women for their religious belief under China’s campaigns in the Uyghur Region.

The report focuses on two broad spheres of religious practice among Uyghur women. The first is the area of everyday religious practice in Uyghur rural communities, including birth and death rituals, and teaching basic prayers and verses of the Quran to village children. These activities are led by women known as büwi, a title of respect given to those who took on leadership roles in rural communities, who taught basic religious, cultural and linguistic knowledge to children, and led women’s religious and cultural activities in rural villages.

The second sphere of religious practice is a relatively recent phenomenon in Uyghur society which developed in the 1990s and became widespread in the 2000s. This sphere involves Uyghur women who embraced the reformist styles of Islam emanating from the Middle East, and studied and taught in unofficial religious schools which were more commonly based in urban areas. Far from emancipating Uyghur women from the shackles of religious oppression, as Chinese government sources claim, the criminalization of their religious activities denies them access to new forms of knowledge, economic opportunities, leadership roles and cosmopolitan networks.

Far from emancipating Uyghur women from the shackles of religious oppression, as Chinese government sources claim, the criminalization of their religious activities denies them access to new forms of knowledge, economic opportunities, leadership roles and cosmopolitan networks.

The persecution of female religious leaders in the rural sphere has major implications for Uyghur community life. The campaigns of 2017 have criminalized the practice of learning to recite verses from the Quran, a basic requirement for Muslims across the world, and one of the fundamental forms of socialization of young Uyghur children.9“‘Eradicating Ideological Viruses’: China’s Campaign of Repression Against Xinjiang’s Muslims,” Human Rights Watch, September 9, 2018, online.

The imprisonment of religious leaders capable of conducting the proper funeral rituals means that Uyghurs are living in fear, not only of persecution but also of the consequences of dying without the proper rituals to send their soul safely on its onward journey. As one of our interviewees commented, “We’re not just afraid of living, we’re also afraid of dying.”

IV. Methodology

The report begins with a brief introduction to the different forms of Uyghur women’s religious practice, based on ethnographic research and published sources. It provides contextual background on China’s religious policy on Islam since the 1950s, and traces the increasingly tight controls on women’s religious practice, teaching, and dress leading up to the mass incarceration of religious women in 2017. Information is drawn from original interviews conducted by this report’s co-author Abduweli Ayup in 2023 in Istanbul: one interview with a relative of a woman currently detained, and five interviews with women who fled China in 2014 or earlier due to religious persecution and are now based in Turkey. The report also includes information drawn from earlier interviews with büwi conducted by Rachel Harris, this report’s other co-author, in the rural south of the Uyghur Region between 2009 and 2012, and one interview with a religious teacher based in Istanbul, also conducted by Rachel Harris in 2022.

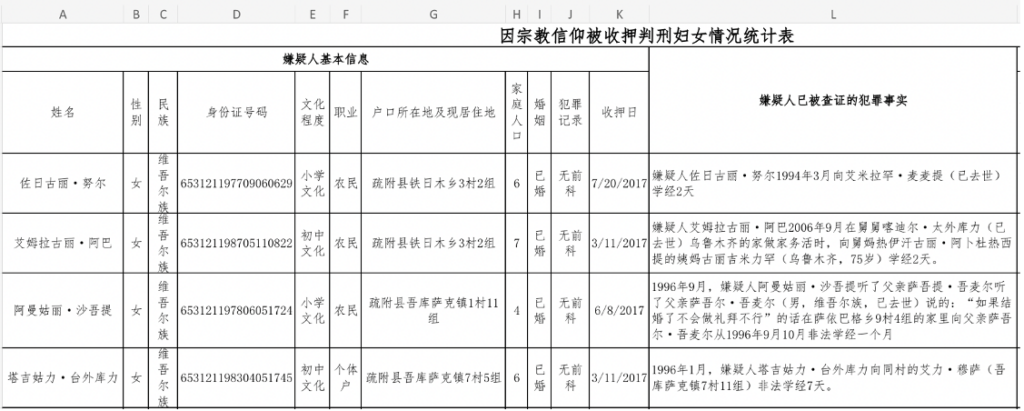

The primary source of data on detentions used in this report is drawn from the Xinjiang Police Files. This important source for our understanding of mass detentions in the Uyghur Region comprises tens of thousands of files dating from the 2000s to the end of 2018, which were obtained by an anonymous hacker who accessed the Public Security Bureau computer systems for Konasheher County (Ch. Shufu) in Kashgar and Tekes County (Ch. Tekesi) in Ili. They include internal spreadsheets from Konasheher showing the personal information of the entire population of the county, some 286,000 individuals.

We have selected from these spreadsheets the records of 408 women detained specifically for engaging in religious practices, typically for wearing religious dress, and acquiring or spreading religious knowledge. We have also extracted a list of 91 women specifically designated in the police records as büwi (Ch. buwei – 布维). We have cross-referenced this data with the details of detained women provided by relatives and recorded on the databases of human rights organizations, primarily the Xinjiang Victims Database.10Xinjiang Victims Database, online.

We have also cross-referenced the names and ID numbers of these detained women with a list of women who are known to have returned from Egypt to the Uyghur Region in 2016. These women are now all presumed detained.11“Egypt: Don’t Deport Uyghurs to China,” Human Rights Watch, July 7, 2017, online. We analyze this data with the help of previously published academic books, articles, and media reports.

V. Female Religious Leaders

Büwi

Tursunhan Imin (图尔荪罕·伊敏)

- ID no. 653121194504050028

- Born: 1945

- Resident of Konasheher County, Toquzaq Township

- Married

- No previous convictions

- Detained: October 7, 2017

- Sentence: Unknown

Ezizigul Memet (艾则孜古丽·麦麦提)

- ID no. 653121197008100667

- Born: 1970

- Resident of Konasheher County, Tashmilik Township

- Married

- No previous convictions

- Detained: June 7, 2017

- Evidence of criminal activities: In February 1976 [age 5 or 6] she illegally studied the Quran for three days with her mother Buhelchem Memet (deceased).

- Sentence: Ten years

Tursungül Ghopur (吐尔逊古丽·吾普尔)

- ID no. 653121199209200620

- Born: 1992

- Resident of Konasheher County, Tashmilik Township

- Married

- No previous convictions

- Detained: March 8, 2017

- Evidence of criminal activities: 1) Between December 2010 and January 2011, she and her sister’s daughter studied the Quran with her father. They studied for around 30 minutes every evening for around a month; (2) Between July and December 2011, she and her sister’s daughter illegally studied the Quran with Ashigul Barat from Kizil Osteng village in Baren Township, Aktau County.

- Sentence: 14 years 11 months

In Uyghur custom, women do not regularly attend the mosque, and so the büwi tradition has provided the main channel for Uyghur women’s religious association and instruction. Büwi were entrusted with teaching the basics of religious practice to children, including memorizing their daily prayers and a few verses from the Quran. Büwi also prepare the bodies of deceased women for burial, and lead the vigil (tünek) at the home of the deceased. These roles are carried out by the imam of the local mosque for men’s funerals. Büwi were also invited to people’s homes to recite the Quran and pray in order to drive out bad luck or illness, and they led local women in religious gatherings called hetme which were held weekly as well as at key points in the Islamic calendar.12We transliterate the Uyghur term as hetme for ease of recognition. Other recognized forms are xetme or khätmä.

Their significant role in the community provided them with elevated social standing and extensive networks of reciprocity.

From interviews in the Uyghur Region obtained before the recent crackdown, between 2009 and 2012, we know that the büwi’s practices continued right through the upheavals of the Cultural Revolution. From the 1980s they were able to practice more openly, and in the 1990s the numbers of women attending these meetings were swelled by the general rise in piety across Uyghur society, as detailed in the next section. Büwi played a central role in village society, as Nisakhan, a practicing büwi in the rural south explained in a 2012 interview:

We büwi have many duties … We wash the bodies of the dead, and we recite hetme every week on Fridays. We recite for the sake of our children and our husbands and our home … Hetme means reciting the Quran and praying. It is like a bullet fired from a gun. It is powerful. It helps people. If someone is sick we do a hetme to cure them, if someone dies we do a hetme to ask forgiveness for their sins. We recite hetme for peace in our land, and to prevent disasters.

Many aspects of their practice are linked to traditions of Sufism which formerly dominated the political and religious life of the region, and were severely persecuted in the early days of the PRC. Women’s rituals do not form an exclusive tradition; their religious practice overlaps and complements men’s practices. Their hetme are impressive communal events, often emotionally charged, and they serve as a form of intercession for the souls of the deceased, for the sick, and for the community. The gatherings include sung prayers called hikmet or monajat, repertoires which form an important part of Uyghur expressive cultural heritage.

The role of büwi encompasses a wide range of specialist knowledge and skills which are transmitted through a lengthy family or community-based apprenticeship. Many büwi inherited the role from their mother or other female relatives and hoped to pass it on to their own daughters. Within village society, büwi were largely respected and even feared for the role they played in dealing with sickness and death. Their significant role in the community provided them with elevated social standing and extensive networks of reciprocity, as Nisakhan explained:

People respect büwi. We wash their bodies when they die, we teach their children, and we teach them. I taught 30 percent of the women in this village to read the Quran. I have 30 mu of land that I plant with cotton.13A mu is a measure of land area approximately one fifteenth of a hectare—30 mu is about two hectares, or about five acres. When the time comes in spring to clear the land they all come to help me. Even Party cadres come to help.

Nisakhan’s explanation of the büwi’s role emphasizes their spiritual power and the highly social nature of their practice, and highlights the social capital associated with this women’s community leadership role. The büwi’s rituals responded to everyday needs within the community, both individual and communal, and their recitation was called into play for calendrical and life-cycle rituals as well as sickness or misfortune.14For further discussion of the role of büwi in Uyghur rural communities, see: Ainiwa’er, Ayinu’er, Shache xian dangdai weiwu’erzu sufei zhuyi jiaotuan nvxintu (buwei) dike’er yishide renleixue diaocha yanjiu, Masters Dissertation: Xinjiang Normal University, 2013; Ildikó Bellér-Hann, Community Matters in Xinjiang 1880–1949: Towards a Historical Anthropology of the Uyghur (Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2008); and Rachel Harris, Soundscapes of Uyghur Islam (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2020).

Ustaz

Since the late 1980s, Islamic revivalist trends emerging from the Middle East have had a profound impact on Uyghur society, as they have in Muslim communities across the former Soviet Union, China, and many other parts of the world. In part, these trends were a response to the relaxing of the tight controls and disruption of religious life during China’s revolutionary period. They represented a revitalization of family and community religious traditions, but they also responded to the increased access to global flows of knowledge that became possible in the 1980s. Thus they can also be understood as part of the transnational spread of Islamic revival movements with their emphasis on a return to “orthodox” practice, scripture, and ethical self-cultivation.15Paula Schrode, “The Dynamics of Orthodoxy and Heterodoxy in Uyghur Religious Practice,” Die Welt des Islams 48 (2008): 394–433; and Edmund Waite, “The Emergence of Muslim Reformism in Contemporary Xinjiang,” in Situating the Uyghurs: between China and Central Asia, eds. Bellér-Hann, Césaro, Harris & Smith (Farnham:Ashgate Press, 2007), 165–181. Uyghur women played an active role in this revival.

In the early years of the 21st century, many Uyghurs were avidly consuming recordings of the recited Quran, which they purchased as VCDs or downloaded as digital files onto their cell phones. Uyghur women organized regular religious tea parties (din chay) to discuss ways of following a religious life, and visited each others’ homes to share recorded sermons and to discuss their contents. Large numbers of women, from independent traders to university students, began to adopt the veil and the habits of daily prayer. They studied Arabic language, learned to recite the Quran and aspired to study abroad in Egypt or other Muslim majority countries.

The religious revival cut across class boundaries, and included many highly educated young urban women. Anthropologist Cindy Huang describes a young woman from Ürümchi who became interested in studying English and in religion. A university student friend explained to her the character-building benefits of daily prayer:

People who pray namaz are very determined people. Because every day in the morning, you wake up and get up and pray namaz. And in the evening in the same kind of difficult conditions you perform namaz. They are firm and determined in their religious faith.16Cindy Huang, “Muslim Women at a Crossroads: Gender and Development in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region,” Ph.D., Anthropology, UC Berkeley, 2009, online.

By the 1990s and into the 2000s, numerous unofficial schools sprang up, teaching Arabic and the Quran to children and adults, both women and men. These developments led to a new class of female religious leaders and teachers, who were addressed as ustaz, or even damolla, a title more commonly applied to prominent male clerics. Our interviewee, Mukerem Ustaz, describes her own journey towards acquiring and teaching religious knowledge:

I learned religion at home from my parents. My father was a pious and knowledgeable man. He taught us how to read the Quran and how to pray, but I didn’t learn much when I was child. I only really began to understand what it means to be Muslim after I started working in the 1980s.

I served as a teacher in Kashgar. I mainly taught adults. I taught some children too, but mostly those whose fathers had been arrested. We sent the children to different teachers according to their age; boys and girls under nine years old went to female teachers, and from ten years old we sent boys to male teachers, girls to female teachers. We didn’t only teach religion, we taught them ethics as well: how to clean their room and their clothes, and how to behave in front of parents, guests and strangers.

We used Arabic text books for children published in Saudi Arabia. We distributed them to every family we knew. Some children studied with us full time because they didn’t have residency permits, so they couldn’t be registered and admitted to state schools. We had other after-school programs aimed at students who were studying at state schools.

Some women traveled to centers of Islamic learning in the Gulf states, Turkey or Egypt, and returned to the Uyghur Region to promote what in their view was “true Islam”: a return to scripture and a rejection of “superstition.” They were often critical of the Sufi-influenced styles of Islam transmitted by büwi. They situated themselves as part of a modern, global form of Islam, and they promoted charity, community revival, and family.

This official framework for Islam exercised control through training institutes for male clerics, and officially recognized mosques which were led and attended by men, and completely ignored women’s religious practice and instruction: an oversight which would continue for another 60 years.

The division we have drawn between these two broad types of female religious leaders—traditional and reformist, rural and urban—should not be understood as a rigid opposition. Village-based büwi also went to the unofficial religious schools to improve their Arabic pronunciation and recitation skills, and ustaz participated in hetme. Damolla also led communal rituals and presided over the life-cycle rituals for births and deaths, and by the 2000s, the unofficial schools could be found in cities and in small towns across the Uyghur Region.

VI. Women and Islam Under the PRC

During the first few years of CCP rule in the Uyghur Region, the Party moved quickly to consolidate its control over Islam. Uyghur religious practice came under a tightly organized system of state controls and carefully defined rights. The Islamic Association of China was formed in 1953. Its roles were to interpret Islamic law in accordance with Party policy, to formulate government regulations on Islam, and to train and oversee religious clerics. It was also responsible for overseeing religious scholarship, and developing the curriculum for China’s ten official Islamic Institutes. A state Islamic Institute was established in Ürümchi to teach a curriculum that included study of the Quran, Hadith, Law, Arabic language, and CCP ideology. Only its graduates could serve as official imams in the region’s mosques.17Graham E. Fuller and Jonathan N. Lipman, “Islam in Xinjiang,” in Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Borderland, ed. S. Frederick Starr (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 2004), 320–52. This official framework for Islam exercised control through training institutes for male clerics, and officially recognized mosques which were led and attended by men, and completely ignored women’s religious practice and instruction: an oversight which would continue for another 60 years.

Mairemgul Memet (麦尔耶姆古丽·麦海提)

- ID no. 653121199008200624

- Born: 1990

- Resident of Qonasheher County, Tashmilik Township

- Married

- No previous convictions

- Detained: Unknown

- Evidence of criminal activities: (1) In September 2012 she saw other women in the village wearing jilbab and thought that she was a Muslim woman and she should also wear the jilbab. Therefore, she wore the jilbab between September 2012 and June 2013; (2) In September 2010 she studied a book on how to recite the Quran and how to pray for around 15 days.

- Sentence: 14 years 11 months

Hasimgul Memetimin (阿斯穆姑丽·麦麦提依明)

- ID no. 653121198503200942

- Born: 1985

- Resident of Qonasheher, Bulaqsu Township

- Married

- No previous convictions

- Detained: June 7, 2017

- Evidence of criminal activities: (1) In September 2004 she illegally studied the Quran with her grandmother for three days; (2) In December 2003 she illegally studied the Quran with her mother-in-law for around 15 days, each time for 15 minutes.

- Sentence: 14 years 11 months

Islam has been repeatedly targeted by the PRC authorities because it has often been perceived as a potential rallying point for Uyghur ethno-nationalism and therefore unrest. From the earliest days of CCP rule, state control over Islam in the Uyghur Region was significantly more repressive than that exercised over the religious practices of the Hui Chinese-speaking Muslims.18Dru Gladney, Dislocating China: Muslims, Minorities, and Other Subaltern Subjects(Chicago: University of Chicago, 2004). In contrast with the Hui Sufi orders in Gansu and Ningxia, the Uyghur Sufi lineages of Kashgar were destroyed.19Thierry Zarcone, “Writing the Religious and Social History of Some Sufi Lodges in Kashgar in the Twentieth Century,” in Kashgar Revisited: Uyghur Studies in Memory of Ambassador Gunnar Jarring, eds. Ildikó Bellér-Hann, Birgit N. Schlyter, and Jun Sugawara (Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2014), 207–231. The old sharia courts and the office of qazi (religious judge) were abolished in 1950, prominent religious leaders were persecuted, and their families placed under strict controls. One of our interviewees, now based in Turkey, recounted:

I come from a religious family. That’s why the Chinese government designated us as a “dangerous family.” They always watched us in case we did something dangerous. My mother’s father was a religious scholar whose specialty was fiqh, Islamic law. My father’s father was a qazi for our county. He was arrested after the Chinese Communist Party came (in the 1950s) and he was buried alive … It was impossible for a family like us in Kashgar to get a passport. I married a man from Hotan and changed my residency; that’s how I managed to leave the country.

The newly constructed system of state-sanctioned Islam effectively collapsed under the growing political radicalism of the late 1950s and 1960s. Islam was classified as part of the “four olds”: customs, cultures, habits, and ideas fostered by the exploiting classes to poison the minds of the people. Religious books were publicly burned, and religious authority figures were humiliated in public meetings organized by the Red Guards. Ordinary people, however, continued to practice and transmit their faith privately.

Following the end of the Cultural Revolution, a period of relative calm and carefully circumscribed tolerance for religious practice prevailed. Officially approved mosques re-opened, and births, marriages and deaths could once more be legally celebrated with religious rituals. The Islamic Institute in Ürümchi resumed teaching male students, officially approved religious literature returned to state bookshops, and the Islamic Association began to organize an official annual hajj for a select group of well-connected pilgrims.

However, in many ways state policies remained hostile to religious practice and transmission. State employees and students, for example, could not be seen to follow any religion, and were not permitted to fast or wear the veil, and the authorities were quick to crack down, often with lethal force, on religious movements that appeared to threaten CCP control over the Uyghur Region.

By the late 1980s, the onset of religious revival, in particular the rise of popular and influential reformist teachers such as Ablikim Mahsum Hajim of Qaghiliq (Ch. Yecheng), began to alarm the authorities. Ablikim Mahsum’s network of religious schools was shut down in 1988 and hundreds of his students were arrested. These restrictions led to social unrest and fed directly into the 1990 Baren uprising, which was suppressed with lethal force.20Rémi Castets, “The Modern Chinese State and strategies of control over Uyghur Islam,” Central Asian Affairs, 3, no. 2 (2015): 221–245; “China: Gross violations of human rights in the Xinjiang Uighur autonomous region,” Amnesty International, March 31, 1999, online.

In the mid-1990s, in the north of the region, religious reformists revived the traditional meshrep male gatherings of Ghulja (Ch. Yining), and used them as a mechanism to tackle alcohol and drug addiction in the community through religious instruction, community activism and football matches.21Jay Dautcher, Down a Narrow Road: Identity and Masculinity in a Uyghur Community in Xinjiang China (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2009). In turn, this movement was suppressed and its leaders arrested, and a demonstration in February 1997 turned into a massacre at the hands of the security forces followed by mass arrests.22“China: Gross violations of human rights in the Xinjiang Uighur autonomous region,” Amnesty International, March 31, 1999, online.

Thus, the last two decades of the 20th century were no golden age for Islam in the Uyghur Region, but the authorities largely tolerated a steady growth in, or return to, religious lifeways. Throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, thousands of new mosques supported by community donations sprang up across the region. Increasing numbers of women adopting modest dress and the habits of daily prayer provided a visible marker of the growth of piety. Less visible but equally important were the numerous unofficial religious schools where large numbers of women served alongside men as teachers.

However, this period was marked by intermittent campaigns against “illegal religious activities,” and women religious leaders were frequently caught up in these crackdowns. Mukerem Ustaz, the teacher from Kashgar recalls:

I got arrested for the first time in 1998. I don’t really know the reason, maybe because of my participation in hetme gatherings, or because of my teaching, or sending my own children to learn religion. I taught my own children Arabic, calligraphy and English. I got arrested again in October, for the same reasons, because of my teaching and participation in hetme. Every time mass arrests started, people like me who had been arrested before were always the target. I got arrested for the third time in 2011, for reading illegal printed books. After that I kept being questioned, and to avoid being arrested again, I left China in 2014.

In November 2001, in a direct response to the US announcement of a “Global War on Terror,” China released a statement asserting the existence of a global network of Uyghur terrorists, supported by “hostile foreign forces,” which posed a major threat to China’s security. The statement named Uyghur human rights and advocacy groups as part of this terrorist network, and described several earlier incidents of unrest as acts of terrorism.23Sean R. Roberts, The War on the Uyghurs: China’s Campaign Against Xinjiang’s Muslims (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020). From this point onwards, the label of “terrorism” would—gradually, inconsistently and arbitrarily—come to be applied to all forms of potential resistance and violent incidents in the region, and also increasingly applied to the everyday peaceful religious activities of Uyghur women.

Rising Repression Post-2009

These days, if you attend too many religious events they’ll classify you as a political criminal … Where do these young people die? Behind the black gate [i.e., in prison camps], and you never know the cause. Five or six years ago they even dared to play Quranic recitations on the village loudspeakers. Now they say it is religious extremism. Apart from prayers at funerals, people are afraid to gather and pray as they used to.24Rabiya Acha, interview, Aksu, August 2012.

On July 5, 2009, a peaceful demonstration in Ürümchi was forcibly suppressed, leading to a tragic outbreak of interethnic violence in the city.25James Millward, “Introduction: Does the 2009 Urumchi violence mark a turning point?” Central Asian Survey, 28, no. 4 (2009): 347–360. The incident was followed by a bout of mass arrests and heightened securitization, and a new period of tighter restrictions on religious teaching, religious gatherings and religious dress, all of which affected women directly. This period marked a turning point in the CCP’s management of Islam in the Uyghur Region, and women became the direct object of government campaigns of re-education and control.

In November 2009, the XUAR Women’s Federation reported that they had conducted educational work to make women “realize that wearing a veil is not a form of expression of ethnic dress but rather of extreme religion, [and] an expression of a type of ignorant and backward way of thinking.” The organization also launched a campaign called “Let Beautiful Hair Flutter, Let Beautiful Faces Be Revealed,” to persuade women to relinquish wearing the hijab.26Report by a XUAR Women’s Federation Party official via the All-China Women’s Federation News site on the People’s Daily, January 12, 2010. Web page now unavailable. Cited in: “Xinjiang Authorities Tighten Controls Over Muslim Women,” Congressional-Executive Commission on China (CECC), April 27, 2010, online. This practice of linking peaceful everyday religious expression to extremism would become a cornerstone of the state campaigns throughout the subsequent decade.

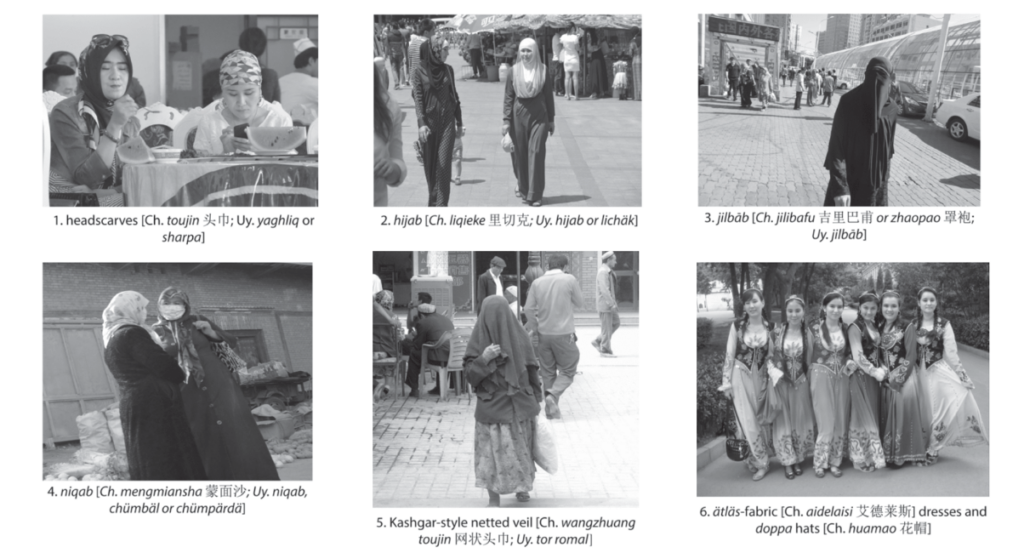

The South China Morning Post reported in 2011 that the “jilbab,” the official term for women’s conservative religious dress, had become widespread in the region during the 2000s. The introduction of this term in Chinese official documents—it is used extensively in the Police Files in sentencing individuals to long terms in prison—is curious because the “jilbab” was not previously part of everyday Uyghur parlance. Uyghurs more commonly spoke of “Arab-style” religious dress (see image on p. 9), a style which did indeed become more visible in the region during the 2000s as part of a global trend to adopt more conservative forms of religious dress. However, it was just one among a wide range of veiling choices adopted by Uyghur women in this period.

Women wearing modest, religious clothing were described in Chinese media and government sources as “blindly affected by extreme religious thought,” and the practice was directly linked to terrorism:

“The black and loose robes enable potential attackers to hide their weapons and, hence, pose a security threat to the safety of the public,” [a government spokesman] said. The Hotan government had launched a campaign to encourage women to avoid such clothing, he said, using slogans telling them to “show off their pretty looks and let their beautiful long hair fly.”28Choi Chi-yuk, “Ban on Islamic dress sparked Uygur attack,” South China Morning Post, July 22, 2011, online.

In practice, the official ban on women’s religious styles of dress expanded beyond the “Arab style” or the “jilbab” full covering, to include the niqab, hijab, and the traditional Kashgar-style netted veil. In the rural south in 2012, signs posted in town centers and villages stated that it was illegal to pray or cover the face in public, subject to fines of up to 2,000 RMB (approx. US$300).

People found praying in the town bazaar were kept in prison overnight, and given 15 days political education. Alongside the police, state employees were also obliged to spend several hours of their work time patrolling the town streets, dressed in army fatigues and supplied with hard hats and large sticks, enforcing the ban on “illegal religious clothing.” Interviewees reported that the effect of this ban was to confine pious women in their homes, as their personal faith did not permit them to appear in public without a head covering.

Interviewees reported that the effect of this ban was to confine pious women in their homes, as their personal faith did not permit them to appear in public without a head covering.

The evidence from this period serves to highlight the often contradictory and rapidly changing nature of state policies on Islam. They also suggest high levels of regional variation in the implementation of central directives, with much harsher implementation of policy in the rural south.

The Co-option of Büwi

In 2009, the regional authorities apparently caught up with the significance of büwi in Uyghur religious life, and rolled out a new framework to register, train and supervise büwi. Similar to the official imam, büwi would be expected to educate local women and even report on their activities. A proposal tabled at the XUAR People’s Political Consultative Conference argued that büwi had previously existed in a “no-man’s land” and should be brought under state oversight. Subsequently, local governments reported on steps taken to strengthen official oversight of büwi and to implement training programs.29“Xinjiang Authorities Train, Seek to Regulate Muslim Women Religious Figures,” CECC, August 20, 2009, online. According to another report by the XUAR Women’s Federation published just one year later in 2010, these programs had successfully “restrained women from participating in illegal religious activities and ethnic separatist activities.”30“Proposal from the 2nd meeting of the 10th XUAR People’s Political Consultative Conference (XUAR PPCC), initiated by the Vice-Chairwoman of the XUAR Women’s Federation,” December 23, 2008. Web page no longer available. Cited in: “Xinjiang Authorities Tighten Controls Over Muslim Women,” CECC, April 27, 2010, online.

One of our interviewees reported her personal experience of a büwi training program in Ürümchi in 2012:

The Ürümchi city religious affairs department set up a government institution in Nanshan to train women to wash the bodies of the dead. The training took four days. They took women from the Tianshan region and Shimigou region … around 45 in total. They taught us how to clean the body, how to clean people who died in traffic accidents, how many meters of cloth to use, and which verses of the Quran to recite. They told us that previously it had been unregulated, and now we were going to pass an exam. This was in May 2012. There were Hui women there too. They took our documents and said they would issue us with a certificate and pay us a salary. There was a five-year plan, so that only accredited people would be allowed to wash bodies. They also taught us political lessons and government policies: don’t engage in any illegal activities, don’t read the Quran for too long, don’t allow people to gather after the washing is finished.

Of note in this account is the extremely short time (four days) allocated to the training. This is in sharp contrast with the years of apprenticeship traditionally required to become a büwi, which would encompass lessons in reciting the Quran, leading prayers and zikr, reciting Uyghur language prayers and praise songs (hikmet and monajat), conducting hetme and tünek rituals, as well as the mechanics of preparing the body for burial. In the official designation the role of the büwi was vastly reduced.

These developments parallel the increased emphasis on training male clerics (imams) at village level during this period. Peter Irwin notes local government reports of 8,000 imams above the village level undergoing political re-education in 2011. Chinese media claimed that this would strengthen the cultivation and training of clerical personnel but Irwin suggests that these measures were intended to monitor and maintain strict control over the imams and their religious teaching.31Peter Irwin, “Islam Dispossessed: China’s Persecution of Uyghur Imams and Religious Figures,” UHRP, May 13, 2021, online.

In addition to this kind of official registration and training of new büwi, established büwi were also called in to be registered and to undergo regular political education sessions. Local government reports from this period suggest that large numbers of büwi were drawn into the system. A report from Hotan (Ch. Hetian), published in 2010, asserts that more than 2,000 Party members had been involved in a contact system with 1,833 büwi.32“Xinjiang Authorities Tighten Controls Over Muslim Women,” CECC, April 27, 2010, online. The very high ratio of cadres to büwi suggests that this may have been an early form of the “becoming family” system of intrusive surveillance within the family home.33Darren Byler, “China’s Government Has Ordered a Million Citizens to Occupy Uighur Homes. Here’s What They Think They’re Doing,” China File, October 24, 2018, online.

However, it is clear from interviews at the time that the system excluded many established büwi and that its implementation was short-lived. One senior büwi, interviewed in rural Aksu (Ch. Akesu) in 2012, said that she had been issued with a permit in 2009, only to have it taken away a year later. Since 2010 she had been banned from conducting any rituals, including those for deaths. She was subject to police harassment, including regular searches of her home, and had become deeply paranoid, fearing spies and listening devices everywhere.

Women were arrested for wearing newly designated “illegal clothing” within the privacy of their own homes, and for participating in newly “illegal religious activities” including tünek funeral vigils.

Another büwi from the same county reported in 2009 that she had been detained for leading a religious gathering: “I was leading a prayer meeting once at night and the police caught us. I was arrested along with one girl from Ürümchi, and another two from Aksu, and I was kept in custody for 15 days.” When we interviewed her again in 2012, she reported that she had been subjected to several substantial fines and two beatings at the hands of local police, but she was nonetheless continuing her practice of leading regular hetme gatherings.

During this period, police harassment of religious women, often within their homes, became commonplace. Women were arrested for wearing newly designated “illegal clothing” within the privacy of their own homes, and for participating in newly “illegal religious activities” including tünek funeral vigils. Numerous media and government reports from the period mention incidents where women were confronted by police, often within their own homes, leading to confrontation with the men of the family which sometimes escalated to protests involving the wider community. These protests were typically forcefully suppressed, often involving the deaths of the protestors, and were subsequently designated as “terrorist incidents.”34“Legitimizing Repression: China’s ‘War on Terror’ Under Xi Jinping and State Policy in East Turkestan,” UHRP, March 3, 2015, online. In contrast with the earlier period, when confrontations with the security forces were largely related to men’s religious activities, in this period government attempts to control women’s religious activities were an important flashpoint of repression.

The Yarkand Incident

One of the most serious of these incidents encompassed a series of violent confrontations in Yarkand County (Ch. Shache) in Kashgar in the south of the Uyghur Region in July 2014. The violence began with a police raid on an “illegal religious gathering” by a group of village women: a tünek vigil to mark the end of Ramadan. Protests by the villagers following this raid led to further police violence and mass arrests. In the aftermath, Chinese state media reported that 96 people were killed in riots which erupted after Uyghur “terrorists” attacked a police station and the authorities reacted with “a resolute crackdown to eradicate terrorists.” This incident provides a striking example of how aggressive policing of women’s peaceful religious activities sparked local resistance, which was forcefully suppressed and subsequently labeled as terrorism.35“East Turkestan: Anniversary of Yarkand Massacre Marked by Uyghur Community amid Chinese Silence,” Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization, July 29, 2016, online. Our interview with an eyewitness reveals new details on the events of that incident:

It was in Ramadan, on July 28 [2014], at midnight I heard noise and people crying. We were all awake, too afraid to sleep. Around 2 a.m. I saw a few women come to our neighborhood. They were all from Elishku town. They didn’t have any shoes on, their dresses were muddy, and they kept crying. They told us that on the night of the 27th, women in Yakatam and Tereklenge villages gathered at several houses to hold tünek vigils while the men went to the local mosque to pray. They said that the police had killed some women and arrested others who took part in the vigils.

About the time of the morning call to prayer, I heard gunshots. At first, I thought they were fireworks, but then I saw a helicopter flying overhead. Our village head asked our neighbors not to go outside. Then I heard the sound of motorcycles and calls of “Allahu Akbar!” The women who had escaped [from those villages] told us that the police came and arrested women house-by-house while they were holding their tünek. When the men came home from their prayer they learned what had happened. Around 200 men went to the police station to ask the authorities to release the women. They closed the gates but the protestors tore them down, and tried to get in. The protest turned into a violent clash, cars were burned, and people got shot.

In the morning I saw protesters starting to move forward to the other end of the road. There were a lot of people, most of them were young. I heard them calling “Let them out, let them out!” Then I heard gunshots. Later I learned that around 30 Uyghur men got shot in front of the mosque. Then I heard a bomb exploding. Later I heard that around 60 Uyghurs died in the bomb blast.

The second day I saw a fire engine come to clean the blood from the streets. They used a high-pressure water jet. I saw the blood streaming down both sides of the road. Later I learned from a friend that they collected the remains of 350 bodies. On the fourth day the propaganda started. That day people in Yarkand learned what happened. The TV and radio stations broadcast that a riot had been pacified, and terrorists had been killed, but the city was still under lockdown. Police started to round up people who were originally from Elishku. According to my friends, 4,800 people from the township were arrested. Neighboring townships were also affected. A police friend told me that altogether around 10,000 men and women were arrested.36Excerpts from a 2023 interview with an eye witness.

Post-2014: Strike Hard Against Terrorism and Extremism

Over the course of 2013 and 2014, a deepening crisis took hold of the region.37“Legitimizing Repression: China’s ‘War on Terror’ Under Xi Jinping and State Policy in East Turkestan,” UHRP, March 3, 2015, online. During this period close to a hundred local violent incidents were reported across the region. Most of these reported incidents involved Uyghur deaths, and they were represented as “terrorist incidents” by Chinese media although many of the confrontations were actually sparked by aggressive policing. By 2014 as the situation deteriorated, a small number of incidents did appear to be taking the form of premeditated, organized violence aimed at civilians, notably the Kunming train station knife attack in March 2014 and the Ürümchi market attack in May 2014.38“China Fights Terrorism and Violent Attacks,” China Daily, 2014 compilation, online. The government used these incidents to justify still greater restrictions on Islam—which was now figured as the root cause of violence—and sanctioned increasingly repressive methods to control the Uyghurs and other Muslim peoples of the region. This moment marked a sea change not only because the rules changed but also because existing rules which had previously been enforced in piecemeal fashion were suddenly enforced with devastating violence.

In May 2014, Xi Jinping called for the construction of “walls made of copper and steel” and “nets spread from the earth to the sky” to defend the Uyghur Region against terrorism.39“Xi urges anti-terrorism ‘nets’ for Xinjiang,” China Daily, May 29, 2014, online. Passports were confiscated and special passes were required for any Uyghurs who wished to travel outside their hometown.40“Xinjiang Seethes under Chinese Crackdown,” New York Times, January 2, 2016, online. Police patrols and checkpoints sprang up across the region to implement a tight net of surveillance which drew on a range of high-tech techniques including security cameras, phone scans, tracking devices on cars, and retina recognition software.41“New Xinjiang Party Boss Boosts Surveillance, Police Patrols,” RFA Uyghur, December 16, 2016, online.

Individual Profile: Chimengul Abduqadir (an interview with her nephew)

Chimengul Abdulkadir’s father, Abdulkadir Damolla was a prominent religious scholar from Peyziwat [Ch. Jiashi, in Kashgar]. He was born into a well-educated family and graduated from the Khanliq medressah in Kashgar in 1956. Chimengul was born on December 30, 1968. She attended primary school, and then was educated by the family. She studied Arabic language, Quran tefsir (interpretation) and other religious knowledge. Abdulkadir Damolla had an apprentice called Abdul Hamit Qari, from Peyziwat, Kizil Boyi town. Chimengul married him in 1984, and they settled in Kizil Boyi. As the woman of the house, she taught religion to women and children, and she also taught Arabic and Quranic knowledge.

There were gatherings for the ladies for reading the Quran, or for funerals, or to recite hikmet or hetme all around Kizil Boyi township, Shaptul township, Jambaz township, and Misha township. In all of those regions she was well-known. She organized these meetings, she recited the Quran, she taught religion, morals, manners, and protecting Uyghur traditions, and she did a lot of work to help people who were poor, sick, or in need.

There were very few women in Peyziwat who could recite the Quran well, give sermons and lead gatherings. In recent years her activities started to discomfort the Chinese. She was detained, and forced to work as a cleaner in the town hall. Her life passed in fear of being arrested.

In 2015 she got a passport to visit Mecca and came to Egypt in February 2016.

While she was living in Egypt, her husband was in Kashgar, and he was threatened by the local police, because she had left the country without official permission. The police told him that she must come back or he would be detained, and they pressured him to call her on the phone and tell her to come back or he would be in trouble.

In July 2016 she went back. She told me that she had been responsible for washing the bodies of women who passed away, and for teaching how to wash bodies. She had also taught the Quran secretly, and she had attended Quran readings. Because of these activities she feared the county or the township government would put her in a camp to learn Chinese and make her clean her ideology. About a week after she returned, she and her husband were detained by the Chinese authorities. We heard that she was sentenced to seven years. We don’t know if it is true or not, but we did hear that both of them are now in jail.42An edited interview with Mehmutjan Abduqadir, nephew of Chimengul Abduqadir, Istanbul, February 2023.

VII. Mass Incarceration of Women for their Religious Belief

Since 2017, people like me started to be arrested. I know my friend Tursungul Henim got arrested, she graduated from the university, and she was teaching at home, like me. She lived opposite the Kerembagh Hospital. Muzepper Qarim’s wife, Mihrigul Memeteli, was also arrested. And there was a lady living in Yawagh, she was teaching there, her name is Patem, she got arrested. Many of my friends who were teaching got arrested: mostly ustaz, and people who sent their children to ustaz.43Mukerem Ustaz, interview, Istanbul, 21 February 2023.

As detailed in the Methodology section above, the “Xinjiang Police Files” include tens of thousands of leaked police files dating from the 2000s to the end of 2018 relating to Konasheher County in Kashgar, and Tekes County in Ili. According to Adrian Zenz, who first released and analyzed this information, they indicate that in 2018 around 12.5 percent of Uyghur adults resident in the county were in some form of internment in re-education, detention, or prison facilities. The files also contain the personal information, photographs and current status (in 2018) of around 8,000 individual detainees in Konasheher.44Adrian Zenz, “The Xinjiang Police Files: Re-Education Camp Security and Political Paranoia in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region,” The Journal of the European Association for Chinese Studies, 3(2022): 263–311.

For this report, we have searched these lists and extracted the names and personal details of 408 women from Konasheher county who were detained in connection with their religious practice. The vast majority of these women are recorded as being farmers, with small numbers of independent small business women and a few medical professionals also appearing in the records.

The detailed information contained in the files includes names given in Chinese characters, ID card numbers, sex, ethnicity, educational level, occupation, address, number of family members, date of arrest (overwhelmingly this took place in the first half of 2017), previous detentions (overwhelmingly they have no previous criminal record), and—the section containing the most information—“evidence of criminal activities.”

According to their records, the majority of women were sentenced for studying the Quran (Ch. xue jing), or more specifically for learning to recite a few verses from the Quran. Other reasons detailed in the files include purchasing or keeping religious books in the home, wearing the “jilbab” (the official term for conservative religious dress); going on a private (rather than a state-organized) hajj; attending illegal religious lessons (Ch. feifa zongjiao jiaoke), listening to an illegal sermon (Ch. taibi like; Uy. tebligh), or even displaying a poster in the home which reproduced phrases from the Quran. A few records include the charge of “organizing a wedding without music” (an officially recognized sign of religious extremism).

The charges typically include extensive details and names of other people involved in the “crimes:” not only the religious teachers they studied with, living or deceased, but also other girls who studied with them, and even the names of people who introduced them to the teacher. This extremely detailed account of the social networks of the accused echoes the insistence in the detention records of other counties across the region, such as the Qaraqash lists, on documenting family, social and religious ties, both contemporary and historical. It is also striking that very often these “criminal activities” date back several decades.45Elise Anderson, Nicole Morgret, and Henryk Szadziewski, “Ideological Transformation”: Records of Mass Detention from Qaraqash, Hotan, UHRP, February 18, 2020, online. All of these women were retrospectively sentenced after China issued its new “de-extremification” regulations in 2018 which effectively criminalized such activities.

Often the “crimes” are recorded as having occurred over a very short time period. Ezizgul Memet46艾则孜古丽·麦麦提, ID no. 653121197008100667, born 1970, resident of Konasheher County, Tashmilik Township. was detained on July 6, 2017. She was charged with illegally studying scripture with her mother Buhelchem Memet (deceased) for three days in or around February 1976, aged five or six years old. She was sentenced to ten years in prison. Tursungul Emet47吐尔逊姑丽·艾麦提, ID no. 653121196806200924, born 1968, resident of Konasheher County, Tashmilik Township. studied the Quran with her mother in 1974 for five days, aged five or six. She was sentenced to 11 years in prison.

Some of the women included on the list were elderly, and would be unlikely, given the conditions in the region’s prisons, to survive their sentences.48See Ruth Ingram, “Elderly Uyghurs Die Alone in Jail,” The China Project, June 22, 2023, online. Patihan Imin49帕提汗·依明, ID no. 653121194712251529, born 1947, resident of Konasheher County, Zhanmei Township. was sentenced to six years in prison in 2017, aged 70. Her stated crimes were that she studied the Quran between April and May 1967, wore a jilbab between 2005 and 2014, and kept an electronic Quran reader in her home.

Without exception, the charges are striking for their minor nature, the extreme level of detail and care which has gone into recording them, and the very lengthy prison sentences attached to practices which lie entirely within the norms of everyday religious observance for millions of Muslims worldwide, and protected as an internationally agreed human rights standard, as laid down in the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights:

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom […] either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.50International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights, (Article 18), online.

In every case we looked at there is a remarkable, indeed shocking, lack of proportionality between crime and sentence. The majority of women on this list are not recorded as religious teachers; their crimes are typically to have studied the Quran. However, the charges against a smaller number of women do include the charge of religious teaching. Several women are charged with teaching Quranic verses to their own children, a crime which earned them seven-year prison sentences. Other women are recorded as having taught adult women.

In every case we looked at there is a remarkable, indeed shocking, lack of proportionality between crime and sentence.

Often the “crimes” occurred several decades before the date of detention. Tunisayim Abdukerim51图尼萨依木·阿卜杜克热木, ID no. 653121197203100945, born 1972, detained April 25, 2017. was sentenced to 13 years 11 months in prison for teaching the Quran to a group of local women for one month in January 1989, when she was 17 years old. Mihrigul Mehet52美和日古丽·买海提, ID no. 653121197804050824, born 1978, resident of Konasheher, Chirem Township, detained February 12, 2017. was sentenced to 18 years 11 months in prison, charged with studying the Quran for 19 months in and around 1998; wearing a face veil in 2000 “under extremist influence”; and teaching the Quran to a local woman in 2013, for ten minutes a day over one week. The longest recorded prison sentence, of 20 years, was given to Aytila Rozi, who was charged with studying and teaching the Quran. Her record states that she learned to read the Quran while working in inner China in 2007, and subsequently taught and studied the Quran in a small group of women between 2009 and 2011.53阿依提拉·如则, ID no. 65312119910308262X, born 1991, resident of Konasheher, Mush Township. The detailed attention to minutiae and the care with which these patently absurd charges are recorded is reminiscent of other periods of mass persecution in global history. The Nazis were also famous for their record keeping.

These entries in the Xinjiang Police Files align with the few detailed reports to which we have access concerning individual women given prison sentences for participating in religious gatherings. In 2022, Radio Free Asia Uyghur Service reported on the case of an elderly woman, Helchem Pazil, one of five women from the same family who were sentenced for taking part in religious gatherings in 2013.54Xinjiang Victims Database, entry 16133, online; Shohret Hoshur, “Elderly Uyghur widow serving 17-year term in Xinjiang women’s prison,” RFA Uyghur, January 25, 2022, online.

Helchem Pazil (海里且木·帕孜里)

- ID no. 652801194401100020

- Born: 1944

- Detained: Unknown

- Evidence of criminal activities: “Inciting ethnic hatred and discrimination” and “disturbing social order.”

- Sentence: Ten years

Helchem’s daughters, Melikizat and Patigul Memet, were incarcerated in the same prison, serving sentences of 20 and seven years respectively. Melikizat was convicted of taking part in a religious gathering and providing a venue for religious observance, while Patigul was convicted of “collectively bringing social disorder” by attending the gatherings. Two other family members were convicted of “disturbing public order and inciting ethnic hatred” and for “hearing and providing a venue for illegal religious preaching.

Halchigul Memet, who was named in the police report as leading the women in their religious meetings, left the region before 2017 and settled in Turkey. She told Radio Free Asia: “We would talk about how to improve our quality of life and help sharpen our religious knowledge … We never had any political or anti-government talks. We only talked about how to improve our well-being and our family’s well-being and how to be traditionally good Muslims.”55Shohret Hoshur, “Five women from Uyghur family sentenced to long prison terms in China’s Xinjiang,” RFA Uyghur, January 21, 2022, online.

The freedom to manifest religion or belief in worship, observance, practice and teaching encompasses a broad range of acts. The concept of worship extends to ritual and ceremonial acts giving direct expression to belief, as well as various practices integral to such acts, including the building of places of worship, the use of ritual formulae and objects, the display of symbols, and the observance of holidays and days of rest. The observance and practice of religion or belief may include not only ceremonial acts but also such customs as the observance of dietary regulations, the wearing of distinctive clothing or head coverings, participation in rituals associated with certain stages of life, and the use of a particular language, customarily spoken by a group. In addition, the practice and teaching of religion or belief includes acts integral to the conduct by religious groups of their basic affairs, such as freedom to choose their religious leaders, priests and teachers, the freedom to establish seminaries or religious schools and the freedom to prepare and distribute religious texts or publications.56Human Rights Committee, general comment 22, Para. 4, online.

Detentions of Registered Büwi

Büwi Helchigul Sidiq (布威海丽且古丽·斯迪克)

- ID no. 653121199107101525

- Born: 1991

- Resident of Konasheher, Zhanmei Township

- Married

- No previous convictions

- Detained: March 12, 2017

- Evidence of criminal activities: Between January and February 2003 [aged 12] she illegally studied the Quran with her grandmother.

- Sentence: Ten years

Bumeryem Kasim (布麦尔耶姆罕·喀斯木)

- ID no. 653121193309180025

- Born: 1933

- Detained: October 7, 2017 (age 84)

- Sentence: Unknown, sent for re-education

Only one of the women on the list of women sentenced in Konasheher for religious reasons is specifically charged with working as a büwi. Bumeryem Memet57布麦尔耶木古丽·买买提, ID no. 653121195908051523, born 1959, resident of Konasheher, Zhanmei Township. was given a prison sentence of eight years for her role as a büwi without official approval. The criminal charge against her states that between April 1995 and October 2014 she washed the bodies of the deceased and recited the Quran at funerals without holding an official religious post, and that she had learned to do this between April 1995 and March 1997. As detailed above, the authorities only began to recognize the role of büwi from 2009, and the requirement to officially register was introduced only in 2010, and so this is another example of retrospective criminalization of previously legal activities.

In addition to the main lists of detainees, the Xinjiang Police Files also include a special list of women designated as büwi. Each of the entries for the 91 women on this list recorded the term buwei (Ch. 布维), i.e., büwi, either under the column marked “criminal activities” or under “remarks.” For most of the women on this list, the reason for detention is recorded simply as “büwi,” and they were sent for re-education with no further details. Some entries on this list provide detailed reasons for detention, including, as with other lists, historical instances of learning the Quran, wearing the jilbab, organizing weddings without music, or keeping religious books in the home.

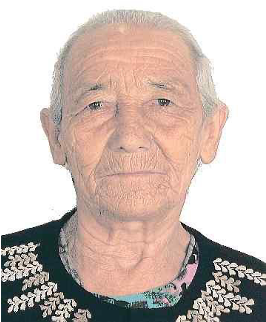

It is shocking for Uyghurs to see these respected elderly women photographed without the hijab that they would have worn in public for most of their adult lives, and more shocking to contemplate the experience of such elderly women subjected to the deprivations and violence of the region’s internment camps.

Many of the women on this list, like Bumeryem Kasim pictured on p. XX), now in her nineties, are elderly. It is shocking for Uyghurs to see these respected elderly women photographed without the hijab that they would have worn in public for most of their adult lives, and more shocking to contemplate the experience of such elderly women subjected to the deprivations and violence of the region’s internment camps.

It is likely that the women on this list were officially registered during the 2010 push to regulate and control büwi. Subsequently, as policy changed, their newly granted official positions were re-designated as criminal behavior and became a reason for detention. The women in this list are recorded only as having been sent for re-education, but we have no direct knowledge of their fate following detention.

Coerced Returns from Egypt and Subsequent Detentions

In early 2017, the Chinese government demanded the return of Uyghur students living in Muslim majority countries, claiming that they were collectively engaged in “separatism” and “religious extremism.” This was soon followed by reports of Chinese authorities detaining family members of these students to coerce them into returning to China. The Chinese government also put pressure on other governments to return the students. UHRP estimates that 292 Uyghurs have been detained or deported from Arab states at China’s behest since 2001.58“Beyond Silence: Collaboration Between Arab States and China in the Transnational Repression of Uyghurs,” UHRP, March 24, 2022, online.

In September 2016, Egypt’s Interior Ministry and China’s Public Security Ministry signed a technical cooperation agreement, pledging increased efforts against terrorism and the sharing of Chinese expertise. Subsequently, according to Human Rights Watch, the Egyptian authorities arrested at least 62 Uyghurs in July 2017 without informing them of the grounds for their detention, denied them access to lawyers and contact with their families, and put at least 12 of them on a flight to China.59“‘Break Their Lineage, Break Their Roots’: China’s Crimes against Humanity Targeting Uyghurs and Other Turkic Muslims,” Human Rights Watch, April 19, 2021, online. The actual numbers are likely to be significantly higher.

Through an anonymous contact, we have obtained the records (names, passport numbers and date of birth) of over 200 Uyghur women who returned from Egypt to the Uyghur Region in the period between 2016 and 2017. On the basis of witness accounts, we believe that all of these women were detained as soon as they arrived in the region. We have cross-referenced this list of names with police records, and with databases held by human rights organizations, and found the records of several women who appear on two or more lists.

Mihrigul Tursun, a prominent camp survivor, has provided detailed testimony on her experience in detention.60Xinjiang Victims Database, entry 2110, online. Tursun went to Egypt to study in 2010; she returned to China with her children in 2015, and was detained for three months. Tursun claims that she was targeted specifically because she had lived in Egypt. She told Radio Free Asia in 2018: “When they interrogate me, they basically ask the same questions: ‘Who are you close to? Who do you know overseas? For which overseas organizations did you work? What was your mission?’ They ask these questions because I lived overseas and because I speak a few foreign languages, so they are trying to label me as a spy.”61“I Did Not Believe I Would Leave Prison in China Alive,” RFA Uyghur, November 1, 2018, online.

In targeting this group of mainly younger women, many of whom traveled to Egypt to study in the country’s respected religious institutions, the Chinese authorities struck against the attempts of Uyghur women to find new forms of agency: self-advancement through studying abroad, and economic opportunities through engaging in international trade. Such efforts must be seen in the context of the severe economic exclusion suffered by Uyghur women. Statistical studies have shown that Uyghur women are the most disadvantaged group in the region; they were much less likely to find employment than Han women, and if employed, they earned significantly less than their Han counterparts.62Sylvie Démurger, “Labor market outcomes of ethnic minorities in urban China,” in Ethnicity and Inequality in China, eds. Björn A. Gustafsson, Reza Hasmath & Sai Ding (London: Routledge, 2020). These exclusions were due to discrimination based on both their religion and their gender.63“Discrimination, Mistreatment and Coercion: Severe Labor Rights Abuses Faced by Uyghurs in China and East Turkestan,” UHRP, April 2017, online.

Saba Mahmood’s influential 2005 book, Politics of Piety, prompted an important shift in understandings of the position of women in Islamic Revival movements. In a challenge to the liberal secular emphasis of the feminist movement, Mahmood highlighted the ways in which reformist Muslim women submitted to apparently subservient roles in the religious hierarchy and yet still managed to exercise considerable agency.64Saba Mahmood, Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005). Since then, scholars have researched women’s Islamic education movements across the world, exploring the reasons for their growth and influence in so many separate and diverse contexts worldwide.65Masooda Bano, Female Islamic Education Movements: The re-democratisation of Islamic knowledge (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017). Anthropologist Cindy Huang conducted ethnographic fieldwork with reformist Uyghur women in the 2000s. As she argues, the reformist movement offered Uyghur women significant opportunities for personal, spiritual, educational and economic development.66Cindy Huang, “Muslim Women at a Crossroads: Gender and Development in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region,” Ph.D., Anthropology, UC Berkeley, 2009, online. China’s promotion of forms of coerced labor in cotton and fish factories seems a poor alternative to the possibilities opened up to them through the networks of reformist Islam.67Ian Urbina, “The Uyghurs Forced to Process the World’s Fish,” October 9, 2023, The New Yorker, online.

Digital Surveillance

Buhejer Ushuraxun (帕提古丽·艾麦提)

- ID no. 654124198507192521

- Born: 1985

- Resident of Gongliu County

- Returned from Egypt in 2016

- Police report issued by Tekes County Police Bureau on July 11, 2017. Big data flags: possessing a driver’s license, visiting Turkey, visiting inner China, lost contact.

Muyesser Muhemmed (帕提古丽·艾麦提)

Born in Atush, Kizilsu [Ch. Atushi (county), Kezilesu (prefecture)]. She went to Egypt to study at Al Azhar University, married in 2006, and moved to Kazakhstan in 2007. She has three children. She returned to China in 2016 to renew her passport, and was detained and sent for re-education. She was released in 2019 but has not been permitted to resume contact with her family in Kazakhstan.68Xinjiang Victims Database, entry 12, online.

Buzeynep Abdureshit

Buzeynep Abdureshit completed a degree in health science in Wuhan in 2013, then studied Quranic Arabic at Al-Azhar University in Egypt. She completed these studies in 2015 and returned to China, planning to study medicine. She was detained on March 29, 2017, in Ürümchi. Her family reported that the police placed a bag over her head and forced her into a car. She was given a seven-year prison sentence on June 5, 2017. She was charged with “assembling a crowd to disturb social order.” Her husband commented that he believes that she was detained simply because she studied in Egypt.69Xinjiang Victims Database, entry 1741, online.

Some of the individual cases which appear in the Xinjiang Police Files provide significant insights into the workings of the surveillance and sentencing system in the Uyghur Region.

Buhejer Ushuraxun appears on our list of women who returned from Egypt to China in 2016. We also found among the leaked documents held by the Xinjiang Victims Database a detailed police report on Buhejer Ushuraxun, created by the Tekes County Police Bureau on July 11, 2017.70Xinjiang Victims Database, N16161, file available on request. No decision on her case is recorded and her current whereabouts are unknown.