A Uyghur Human Rights Project report by Abdullah Qazanchi with significant research contributions by Abduweli Ayup. Read our press statement on the report here, and download the full report in here.

I. Key Findings

- We suspect at least 312 Uyghur and other Turkic Muslim intellectual and cultural elites are currently being held in some form of detention

- The Chinese government persecution of Uyghur and other Turkic Muslim intellectual and cultural elites constitutes a significant component of China’s genocidal campaign in East Turkistan

- As a component of genocide, the assault on intellectual and cultural elites may constitute a new form of eliticide meant to exterminate Uyghur (and other) cultural identity

II. Introduction

Credible sources estimate the Chinese authorities have arbitrarily detained at least upwards of 1 million Uyghurs in concentration camps, prisons, and other detention facilities in East Turkistan since 2017.1For internment figures, including the upper estimate of 1.8 million in concentration camps as of 2019, see Adrian Zenz, “‘Wash Brains, Cleanse Hearts’: Evidence from Chinese Government Documents about the Nature and Extent of Xinjiang’s Extrajudicial Internment Campaign,” Journal of Political Risk 7, no. 11, (November 2019), https://www.jpolrisk.com/wash-brains-cleanse-hearts/. For a recent investigation showing that the XUAR government is capable of detaining a minimum of 1.01 million individuals at a single time, see Megha Rajagopalan and Allison Killing, “China Can Lock Up a Million Muslims in Xinjian at Once,” Buzzfeed News, July 21, 2021, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/meghara/china-camps-prisons-xinjiang-muslims-size. The Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP) has analyzed data gathered by Uyghur diaspora members to document a minimum of 312 Uyghur, Kazakh, and Kyrgyz intellectual and cultural elites whom we suspect are detained or imprisoned as of late 2021.

Several cases of targeted Uyghur intellectual and cultural elites have received wide coverage in the international press, including those of folklore expert Dr. Rahile Dawut;2Chris Buckley and Austin Ramzy, “Star Scholar Disappears as Crackdown Engulfs Western China,” New York Times, August 10, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/ 08/10/world/asia/china-xinjiang-rahile-dawut.html. Xinjiang University president and professor Tashpolat Teyip;3Andreas Illmer, “Tashpolat Tiyip: The Uighur Leading Geographer Who Vanished in China,” BBC, October 11, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-49956088. scholar and poet Dr. Abduqadir Jalaleddin;4“Prominent Uyghur Scholar Detained in Xinjiang Capital Urumqi: Official,” Radio Free Asia, April 25, 2018, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/scholar-04252018140407.html former Xinjiang Medical University president and medical scholar Halmurat Ghopur;5“Prominent Uyghur Intellectual Given Two-Year Suspended Death Sentence For ‘Separatism’,” Radio Free Asia, September 28, 2018, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/sentence-09282018145150.html and singer Ablajan Awut Ayup.6Rachel Harris, “Uyghur Pop Star Detained in China,” Freemuse, June 11, 2018, https://freemuse.org/news/uyghur-pop-star-detained-in-china/

The evidence we have gathered and analyzed suggests that the persecution of intellectual and cultural elites (hereafter “elites”) runs much deeper and wider than these widely publicized cases alone suggest. The voices of hundreds of other persecuted Uyghur and other elites continue to remain muted, including Xinjiang Normal University literature professor and dean Abdubesir Shukuri,7“Mektep da’iriliri proféssor Abdubesir Shüküri’ning tutqun qilinghanliqini inkar qilmidi” [School leadership does not refute the detention of Professor Abdubesir Shüküri], Radio Free Asia, October 17, 2021, https://www.rfa.org/uyghur/xewerler/qanun/besir-shukir-10172018144706.html literature teacher and poet Gulnisa Imin, and young scholar Dr. Exmet Momin Tarimi, among hundreds of others. (We explore each of these three cases in more detail in Section IV. of this briefing.)

Additionally, several prominent elites have served or are serving harsh sentences handed down prior to Spring 2017, when the mass internment drive began in earnest. For example, Ilham Tohti, an economics professor at Minzu University in Beijing, was ultimately persecuted on account of advocacy for implementation of regional autonomy laws in China and moderate criticism of the Chinese government’s discriminatory policies toward Uyghurs. He was found guilty of separatism by the Chinese authorities and sentenced to life imprisonment in 2014. Other prominent cases include those of author Nurmemet Yasin, who reportedly died in 2011 while serving a sentence of ten years’ imprisonment,8Amnesty International, “China: Uighur writer’s death in prison would be bitter blow,” January 2, 2013, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2013/01/china-uighur-writer-s-death-prison-bitter-blow-freedom/ and literary critic Yalqun Rozi, who is currently serving a sentence of more than a decade’s imprisonment for “inciting subversion of state power,” which was handed down in 2016.9Dake Kang, “Correction: China-Xinjiang-Banished Textbooks story,” Associated Press, September 3, 2019, https://apnews.com/article/4f5f57213e3546ab9bd1be01dfb510d3

The evidence we have gathered and analyzed suggests that the persecution of intellectual and cultural elites runs much deeper and wider than these widely publicized cases alone suggest.

The current number of 312 detained intellectual and cultural elites is an update of earlier UHRP research. We have previously released four briefings documenting the persecution of Uyghur intellectuals:

- October 2018: 231 intellectuals forcibly interned in political indoctrination camps;

- January 2019: 338 scholars and students targeted in what we then referred to as the Chinese state’s “cultural cleansing” campaign;

- March 2019: 386 cases of detained, imprisoned, or disappeared intellectuals and students; and

- May 2019: 435 cases, including 125 students.

The current list of detained elites excludes students as well as individuals who have been released from detention, as well as several elites who died while detained or shortly after their release.10The question of deaths in custody is an important one that has not yet been addressed in systematic research. For just one example of such a death, see Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Uyghur Human Rights Project Condemns Death in Custody of Scholar Muhammad Salih Hajim,” January 29, 2018, https://uhrp.org/statement/ uyghur-human-rights-project-condemns-death-in-custody-of-scholar-muhammad-salih-hajim/

The number 312 includes only cases about which we have been able to gather information; the real number of detained elites is likely much higher. The data gathered in our research suggests a targeted campaign to punish intellectual and cultural life. In outlining this aspect of China’s multi-pronged and brutal campaign of social re-engineering, we suggest that the attack on Uyghur and other elites, which is led by the Chinese party-state, is evidence of intent to destroy Uyghur cultural identity by crippling intellectual and cultural production.

This campaign against intellectual and cultural producers is intended to destroy Uyghurs’ cultural distinctiveness and facilitate their assimilation into a homogeneous China.

This campaign against intellectual and cultural producers is intended to destroy Uyghurs’ cultural distinctiveness and facilitate their assimilation into a homogeneous China. Professor Sean R. Roberts has argued that the intent behind the ongoing campaign is to once and for all forcibly integrate the Uyghurs into the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) version of “modernity,” something Uyghurs have long resisted.11Sean R Roberts, The War on the Uyghurs: China’s Internal Campaign Against a Muslim Minority (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020), 4. Roberts sees continuities between this campaign and other settler-colonial projects, “which sought to break the will and destroy the communities of native populations, quarantine and decimate large portions of their populations, and marginalize the remainder while subjecting them to forced assimilation.”12Ibid., 5.

Our research raises a fundamental ethical question to institutions and individuals in the global academic community over their collaboration with a government that is so brutally attacking Uyghur and other elites. Can exchanges and scholarly cooperation with state institutions in the PRC continue as normal at a time when the state has thrown at least 312 intellectual and cultural producers in East Turkistan into camps and prisons?

We urgently call upon universities, researchers, and cultural programs to suspend all cooperation with the Chinese Ministry of Education until the camps are closed, imprisoned and sentenced civilians released and compensated, and perpetrators brought to justice. In the final section of this briefing, we make a number of other targeted policy recommendations to a variety of actors.

III. Sources

Since 2017, Chinese authorities have routinely refused to publish any official data on the campaign of mass internment and incarceration. Moreover, the brutal security crackdown and increased internet (and other) censorship make it impossible to directly contact Uyghurs in East Turkistan to obtain information. These realities have posed challenges for researchers trying to understand the scope of repression. However, a proliferation of verified evidence, including leaked government documents and survivor testimony, has proven invaluable in providing a paper trail of China’s atrocity crimes.13 Magnus Fiskesjö, “China’s ‘re-education’ / concentration camps in Xinjiang / East Turkistan and the campaign of forced assimilation and genocide targeting Uyghurs, Kazakhs, etc. Bibliography of Select News Reports & Academic Works,” Uyghur Human Rights Project, last updated November 17, 2021, https://uhrp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Chinas-re-education-concentration-camps-in-Xinjiang-BIBLIOGRAPHY-3.pdf.

In collaboration with Abduweli Ayup of Uyghur Yardem, or Uyghur Hjelp, we have compiled a database of 312 detained or imprisoned elites whom we believe are currently being held in some form of extralegal detention after disappearing between 2016 and 2021. In collating this database, we have defined intellectual and cultural elites as individuals who have received a university degree or diploma and/or who work in fields where they have made visible contributions to public intellectual, cultural, and/or political life through writings, lectures, performances, and other public-facing activity.

Our criteria for inclusion in the database included that the individuals must be non-student professionals and/or practitioners (including retired individuals) whom we suspect, based on evidence described in more detail below, are currently held in some form of arbitrary and unjust state custody. The current database excludes a number of individuals whose names appeared in earlier lists published by UHRP, including university students, individuals who appear to have been released, and individuals who died while in or shortly after release.

The database consists of 8 columns presenting the following information: detainee name; biological sex; profession and/or title; institutional affiliation; other position(s) and/or professional work;14 Many elites on the list have received a level of public notoriety and influence not from their primary profession (i.e., the employment through which they earn a living) but rather from intellectual, cultural, or other work they perform outside their main job. Some of the most prolific poets among Uyghurs, for example, have primary careers in non-literary fields. additional information (where available); link to entry in Xinjiang Victims Database (where applicable); and our level of confidence in the information (“verified” or “lacking details”). The full database is available for viewing on our website here, and in a publicly accessible Google Sheet.

To compile accurate and reliable data while minimizing the likelihood of errors, we have gathered and analyzed a variety of sources:

1. Chinese websites. In our earliest stage of research, we examined publicly available information on Chinese websites. In a number of high-profile cases early in the mass internment campaign, universities deleted the online biographies of academics almost immediately upon the academics’ disappearance.15 Including president of Xinjiang University and professor Tashpolat Teyip, Xinjiang University professor Nebijan Hebibulla, Xinjiang Normal University professor Nurmuhemmet Ömer Uchqun, and Xinjiang University of Finance and Economics lecturer Dr. Tursunjan Behti, among others. We thus began our work by searching the websites of universities and other government-run institutions for the biographies of elites known to have worked at these institutions in the recent past.

2. Interviews. We also attempted to confirm as many cases as possible by contacting individuals’ relatives and colleagues in the diaspora. In several cases, we obtained information about disappeared elites directly from their relatives and colleagues living outside the Uyghur Region. We then conducted a series of informal and semi-structured interviews to collect information on the elites’ life stories and work. In several cases, Uyghur intellectuals in the diaspora, including three scholars previously based at Northwest Minzu University, reported extrajudicial detentions of their colleagues to us. Our researchers further collected data from other university members, colleagues, and close relatives to confirm the claim that the faculty member might have been arrested. (Section IV. of this report briefly presents stories of three detained Uyghur elites, which we wrote based on several such interviews.)

3. Leaked records of mass internment, including the Qaraqash Document and Aksu List. Leaked documents were a further source of information in our research. For example, Lenovo software engineer Nurmemet Hamut and high school teacher Tursun Turghun both appeared in the Aksu List.16[4] Human Rights Watch, “China: Big Data Program Targets Xinjiang’s Muslims,” December 9, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/12/09/china-big-data-program-targets-xinjiangs-muslims#. For reporting on the Qaraqash List, see Uyghur Human Rights Project, “‘Ideological Transformation’: Records of Mass Detention from Qaraqash, Hotan,” February 18, 2020, https://docs.uhrp.org/pdf/UHRP_Qara qashDocument.pdf and Adrian Zenz, “The Karakax List: Dissecting the Anatomy of Beijing’s Internment Drive in Xinjiang,” Journal of Political Risk vol. 8 no. 2, February 2020, https://www.jpolrisk.com/karakax/. These leaked documents are significant in displaying some of the most robust evidence that Beijing is actively persecuting and punishing regular cultural and religious practices, of which intellectual and cultural elites are often innovators and gatekeepers.

4. Public and private databases. To compile our list and verify cases, we also consulted information in public and private databases documenting the disappearance of Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslim peoples into camps and prisons in East Turkistan. These sources include the Xinjiang Victims Database (public) as well as the Uyghur Transitional Justice Database (private).

There are several limitations to our work. The first is that we have been unable to fully verify the cases of all 312 elites on the list. We have a high degree of confidence in 109 of the 312 cases and have marked the remaining 203 as “lacking details.” A second limitation involves the comprehensiveness of this report. We suspect that the number of 312 disappeared Uyghur elites is conservative and that the actual figure is likely much higher.

Despite these limitations, we are confident that our work fulfills a vital need in publicizing the cases of at least some disappeared elites and demanding accountability for their disappearance. We also believe that the information presented here and in our earlier reporting provides compelling evidence that the Chinese Communist Party and government of the PRC are committing a new form of eliticide against Uyghur and other Turkic Muslim elites.

Any errors of inclusion or omission are the direct result of the Chinese authorities’ refusal to provide the international community with accurate, reliable information. We are open to consider credible evidence, from state or other sources, that individuals listed in this report are not in some form of detention. Individuals and organizations may submit evidence, including for cases not listed in our current database, for consideration by UHRP by emailing our organization at info@uhrp.org.

IV. Persecuted Uyghur Elites: Three Profiles

Gulnisa Imin: Literature Teacher and Poet

Gulnisa Imin, a Uyghur literature teacher and talented poet, was detained in December 2017, reportedly for her ideas about preserving and promoting the Uyghur language and culture.17Xinjiang Victims Database, “Ethnic-Minority Individuals Interned since January 2017,” May 5, 2020, https://mail.shahit.biz/eng/#9041 Imin’s poetry has garnered wide acclaim on online social media platforms such as WeChat and QQ,18QQ is a popular online service in China operated by Tencent and includes both instant messaging and a web portal. where many Uyghur authors have long self-published poetry as a means of circumventing exclusionary publishing practices.

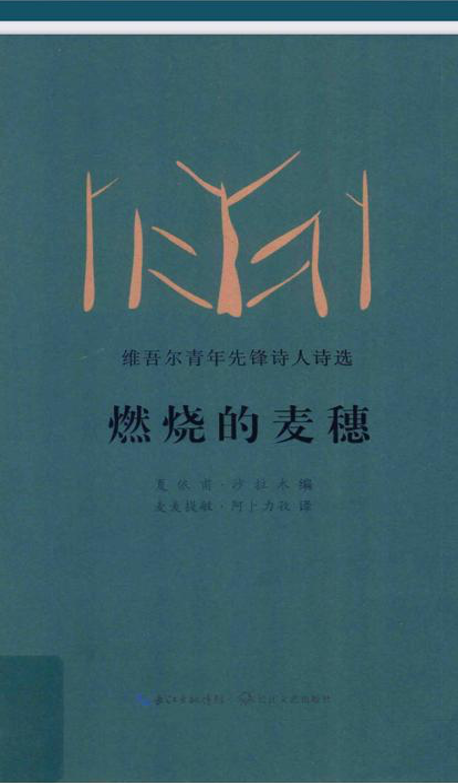

Some of Ms. Gulnisa’s poetry has been translated into Chinese and Japanese. For example, her poetry collection “燃烧的麦穗” (Burning wheat) was published by Changjiang Literature and Art Press in 2016.19Gulnisa Imin, “燃烧的麦穗: 维吾尔青年先锋诗人诗选” [Burning wheat], Changjiang Literature and Art Press (Changjiang, PRC), 2016. Another collection of her poetry, titled “红月亮诗刊” (Red Moon Poetry Collection), was published in the same year.20Gulnisa Imin, “红月亮诗刊” [Red moon poetry collection], Unity Press (Beijing), 2016. Her poetry also appeared in a Japanese-language publication of translated poetry by Uyghur avant-garde poets.21 Anonymous interviewee, Interview by Abdulla Qazanchi, May 20, 2021.

Ms. Gulnisa is a prolific writer and has produced nearly one thousand poems over the course of her writing life. In 2016, she was inspired by the world-famous and beloved “One Thousand and One Nights” and began writing one poem each night. Sadly, she was only able to write and self-publish to QQ approximately 400 poems prior to her disappearance in 2017. According to an anonymous source, none of her poetry expressed opinions or commentary on party-state policies in East Turkistan.22Ibid. On December 6, 2021, two days before this briefing went to press, the Uyghur service of Radio Free Asia reported that Ms. Gulnisa has been sentenced to 17 years, 6 months’ imprisonment on still-unknown charges.23“”Mingbir kéche” shé’irining aptori gülnisa imin 17 yil 6 ayliq késilgen” [Gulnisa Imin, author of ‘One thousand and one nights,’ sentenced to 17 years, 6 months’ imprisonment], Radio Free Asia, December 6, 2021, https://www.rfa.org/uyghur/ xewerler/ming-bir-keche-12062021140942.html

Abdubesir Shukuri: Literature Professor

Abdubesir Shukuri, Professor and Dean of the Department of Literature at Xinjiang Normal University, has been held in custody since 2017. As is the case with many other persecuted Uyghur intellectuals, there are scarce details about his disappearance and current whereabouts. He is a revered expert on Uyghur language and cultural heritage, and a renowned scholar at home and abroad. He is a member of the Permanent International Altaistic Conference (PIAC), Xinjiang Authors Association, Xinjiang Writers and Artists’ Association, and Association of China Uyghur Classic Literature and Twelve Muqams.

Professor Abdubesir Shukuri is distinguished for his prolific contributions to Uyghur classical literature and Turkology. He has published more than 50 books and articles in Uyghur and Chinese on a broad range of topics, including literature, philosophy, ancient religions, and belief systems in Turkic Central Asia.24[1] His most significant scholarly contributions include titles such as Uyghur xelq dastani Aqulumberdixan ve shaman dini” (Uyghur folk epic Aqulumberdixan and shamanism), Tutimining meniwi asasi heqqide” (On the spiritual foundations of the totem), Oghuzname ve Manas (Oghuzname and Manas), and Yengi pilatonizim ve mistitizim” (New Platonism and mysticism), among many others. Furthermore, he received a research award in social sciences from the government of the Uyghur Autonomous Region in 1995 for an article titled “Qedimki Uyghurlarning at medeniyiti heqqide deslepki izdinish” (An initial study on the horse culture of ancient Uyghurs). Professor Abdubesir is also a renowned literary critic with more than 30 critical essays among his publications. In 1994 his essay “Ghora xiyallar” (Underripe imagery) was awarded the Khantengri Literature Award, the most distinguished honor in Uyghur literature. He also published a highly regarded book of literary criticism titled Edebiyatimiz néme deydu? (What does our literature say?).25 Abdubesir Shukri, Edebiyatimiz néme deydu? [What does our literature say?] (Ürümchi, Xinjiang Nationalities Press, 2010).

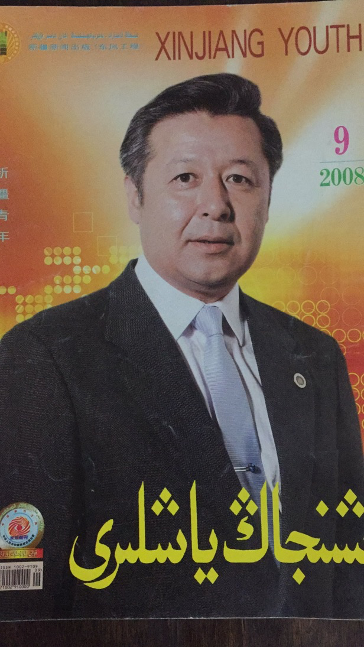

journal Xinjiang Youth in 2008.

Professor Abdubesir has served as a chief editor of intermediate and high-school textbooks for Uyghur language and literature. He also published a university-level textbook on oratory. Moreover, Professor Abdubesir’s academic work was not limited to research and criticism but also included literary translations such as Orxun abidiliri (The Orkhon scriptures), Turki tillar (Turkic languages), and Turk-runik yéziqidiki abidiler (Ancient Turkic Runic inscriptions).26 Türkizat Abdubesir (Professor Abdubesir Shukuri’s son, based in Germany), Interview by Abdulla Qazanchi, May 23, 2021.

Exmet Momin Tarimi: Calligrapher, Scholar, and Editor

Exmet Momin Tarimi is a skilled calligrapher and scholar of Uyghur history who previously worked as an editor at Xinjiang People’s Press. Mr. Exmet was simultaneously pursuing his Ph.D. in history at Nanjing University and was set to complete a doctoral dissertation on Yaqup Beg, a statesman and historical figure who established an independent state called the Kingdom of Kashgaria in 1864, around the time of his disappearance in December 2017. His thesis advisor, Professor Liu at Nanjing University, initially disagreed with the research on Yaqup Beg because the research question is extremely sensitive and examines self-governing political rule in East Turkistan.27Anonymous informant, Interview by Abdulla Qazanchi, July 20, 2021.

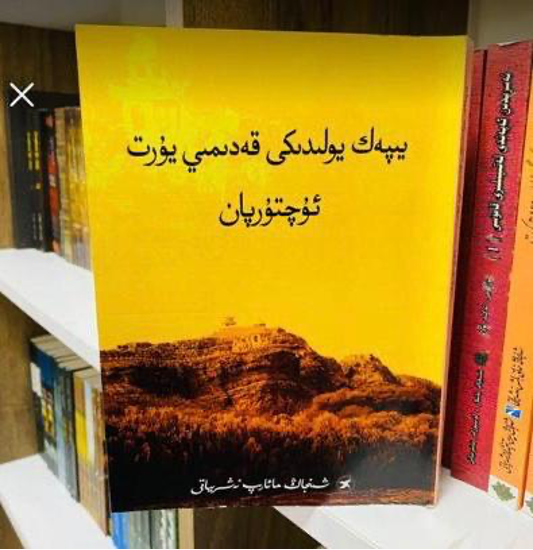

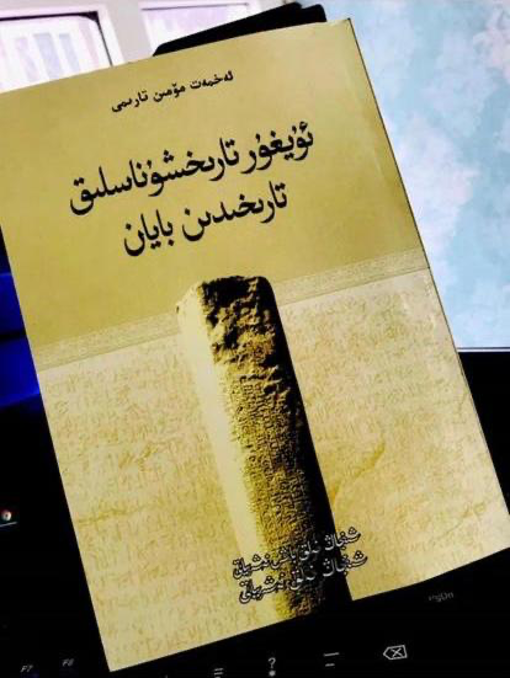

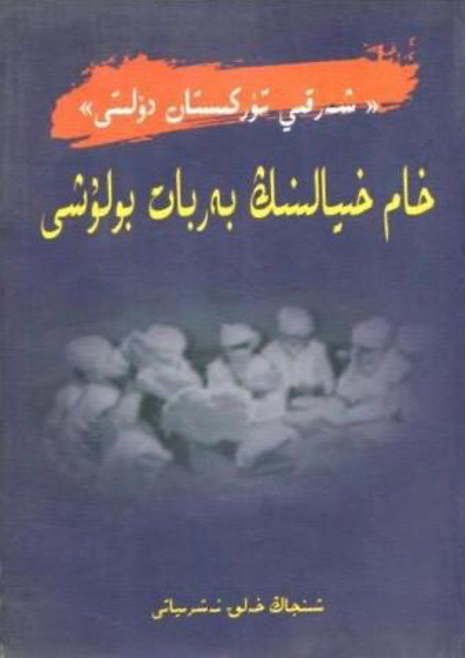

Mr. Exmet has published more than 70 academic articles and many books, including Yipek yolidiki qedimiy yurt Uchturpan (The pearl in the Silk Road: Uchturpan),28Exmet Momin Tarimi, “Yipek Yolidiki Qedimiy Yurt Uchturpan” [The Pearl in the Silk Road: Uchturpan] (Urumchi: Xinjiang Education Press, 2015). Uyghur tarixshunasliq tarixidin bayan (Statement on the history of Uyghur historiography),29Exmet Momin Tarimi, “Uyghur Tarixshunasliq Tarixidin Bayan” [Statement on the History of Uyghur Historiography] (Urumchi: Xinjiang People`s Press, 2014). and Tarim yürikidiki ot (The fire in the heart of the Tarim), which were praised by the government and gained wide recognition among Uyghur readers. In addition, Tarimi translated the book Sherqi Turkistan döliti xam xiyalining berbat bolushi (Ruining the pipe dream of the East Turkistan State), written in Chinese by scholars Ma Dazheng and Shu Jianying.30 Exmet Momin Tarimi (translator), Sherqi Turkistan döliti xam xiyalining berbat bolushi” [Ruining the pipe dream of the East Turkistan state] (Ürümchi: Xinjiang People`s Press, 2007). However, the book was banned and collected by the authorities shortly after its publication.

(banned and collected) (right).

V. Persecution of Intellectual and Cultural Elites Over Time

The Chinese government has a long history of persecuting Uyghur elites. From the purges of East Turkistan nationalists in the Anti-Rightist Campaign of the late 1950s to the present-day detentions of Uyghur writers and intellectuals, the government has long suppressed Uyghur freedom of speech by placing limits on intellectual and cultural production. Chinese Public Security agents arrested Nurmemet Yasin in 2004 for publishing a story titled “Wild Pigeon” in a local literary journal in Kashgar. On January 15, 2005, a local police officer in Kashgar confirmed to the Uyghur Service of Radio Free Asia that Nurmemet Yasin had been arrested three and a half months earlier for “spreading separatist ideas” in his story, which was an allegory about a pigeon that dies by suicide after it is unable to escape its cage.31Amnesty International, “China: Uighur The author reportedly died in prison in 2011.32Ibid.

Chinese authorities have been unequivocal in suppressing Uyghur voices that speak out against rights abuses leveled against the Uyghur people. Journalist Abdughani Memetemin was imprisoned in 2003 for “supplying state secrets to an organization outside the country.”33Amnesty International, “China: More Activists Stand Up for Human Rights, Despite Risks,” December 6, 2004, https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/ ASA17/059/2004/en/ Teacher Abdulla Jamal was arrested in 2005 after he submitted a manuscript for publication that Chinese authorities claimed was separatist in intent.34“Uyghur Historian Released from Prison” (The Congressional-Executive Commission on China, March 12, 2009). Mehbube Ablesh, a Xinjiang People’s Radio Station journalist, was arrested in 2008 for writing critically about “bilingual” education.35“Uyghur Political Prisoners Mehbube Ablesh’s and Abdulghani Memetemin’s Prison Sentences Expire” (The Congressional-Executive Commission on China, October 18, 2011). Despite its name, “bilingual” education is effectively monolingual through its provision of classes only or almost exclusively in the Mandarin language. As Human Rights Watch points out, these prisoners of conscience are victims of an “official policy that criticism or minority expression in art and literature can be deemed a disguised form of secessionism, its author a criminal or even ‘terrorist.’”36Human Rights Watch, “Devastating Blows Religious Repression of Uighurs in Xinjiang,” April 2005, https://www.hrw.org/reports/china0405.pdf

The current assault on Uyghur intellectual and cultural elites from 2017 onward represents a significant escalation of persecution, as even Uyghurs loyal to the state and party are now subject to absurd allegations such as being “two-faced,” i.e., politically hypocritical.37Mamtimin Ala, “Turn in the Two-Faced: The Plight of Uyghur Intellectuals,” The Diplomat, October 12, 2018 , https://thediplomat.com/2018/10/turn-in-the-two-faced-the-plight-of-uyghur-intellectuals/ Former vice president of Xinjiang University Azat Sultan was removed from his post and detained in 2018 for exhibiting “two-faced” tendencies.38“Uyghur Former Xinjiang University Vice President Detained for ‘Two-Faced’ Tendencies,” Radio Free Asia, September 24, 2018, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/professor-09242018164800.html. As of 2021, Azat Sultan appears to have been released from custody. Many other elites have disappeared on similar charges.

More recently, CGTN accused Uyghur intellectuals of fostering separatist tendencies and seeking the establishment of an Islamic caliphate. On April 2, 2021, the network broadcast a propaganda film titled “The War in the Shadows: Challenges of Fighting Terrorism in Xinjiang.” The narrative central to the film claimed that the portrayal of the historical figure and revolutionary Uyghur leader Ehmetjan Qasimi in textbooks for primary and middle schools constituted an act of terrorism and separatism, and that the story of the “Yette qizlirim” (Seven girls), telling of the struggle and sacrifice of Uyghurs during the Manchu regime in eighteenth-century East Turkistan, was similarly “terroristic” in nature.39“The War in the Shadows: Challenges of Fighting Terrorism in Xinjiang,” CGTN, April 02, 2021, https://news.cgtn.com/news/2021-04-02/The-war-in-the-shadows-Challenges-of-fighting-terrorism-in-Xinjiang-Z7AhMWRPy0/index.html

The current assault on Uyghur intellectual and cultural elites from 2017 onward represents a significant escalation of persecution […]

These textbooks, published in 2003 and 2009, had previously made it through the censors; however, by 2017 they became symbols of “extreme ideologies,” evidence of supposed crimes that included “inciting ethnic hatred,” “pushing religious extremism,” and “fabricating separatist materials.”40Ibid. Those people who organized, edited, and printed the textbook became primary targets in the post-2016 crackdown. For example, Former Deputy Secretary of the Xinjiang Education and Work Committee Sattar Sawut received a two-year suspended death sentence, while Alimjan Memtimin (Deputy Director-General of the Xinjiang Education Department), Tahir Nasir (former president of the Education Publishing House), and other editors were given life sentences.

The current measures in East Turkistan are taking place as the Chinese state moves to control intangible Uyghur cultural heritage, such as music, dance, literature, and history. The Chinese government seeks to frame Uyghur cultural and intellectual production as small parts of Chinese heritage, allowing them to take only narrow officially defined forms.41yghur Human Rights Project, “The Persecution of the Intellectuals in the Uyghur Region: Disappeared Forever?” October 2018, https://docs.uhrp.org/pdf/UHRP_ Disappeared_Forever_.pdf As Georgetown University professor James Millward has put it, “cultural cleansing is Beijing’s attempt to find a final solution to the Xinjiang problem.”42Gerry Shih, “China’s Mass Indoctrination Camps Evoke Cultural Revolution,” AP News, May 18, 2018, https://apnews.com/article/kazakhstan-ap-top-news-international-news-china-china-clamps-down-6e151296fb194f85ba69a8babd972e4b

China targets Uyghur and other intellectual and cultural elites because they serve as a key repository of ethnic identity and cultural existence. As custodians of cultural heritage, elites have long been a driving force in shaping collective memory, shared values, and norms. In this regard, the persecution of Uyghur and other elites is evidence of the Party-state’s intent to deprive the Uyghur, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, and other populations of leadership and of any chance for self-preservation. We see this assault as a form of twenty-first century eliticide that suffocates the store of collective knowledge while preserving the physical bodies of the intellectual and cultural elite.

VI. Conclusion

China’s campaign against Uyghurs has already become a pressing global issue. Nevertheless, in spite of widespread concern, the international community has made few concerted attempts to hold China accountable for its atrocities. Despite growing media attention, a large body of evidence, and a series of attempts by the governments of several countries, including Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, Lithuania, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States, to recognize China’s actions as genocide, the global response has remained relatively modest.43Uyghur Human Rights Project, “International Response to the Uyghur Crisis,” last updated August 16, 2021, last accessed October 7, 2021, https://uhrp.org/responses/ The international community must not turn a blind eye to the persecution of Uyghur elites, who serve as guardians and innovators of cultural identity.

A terrifying human disaster is currently unfolding in East Turkistan, where an unknown number of Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslim peoples remain detained in camps and prisons. Among them, a minimum hundreds of elites continue to be subjugated to collective and unjust punishment on account of their ethnoreligious belonging and cultural identity. The Chinese government justifies these dystopian measures as “voluntary re-education” to eradicate religious extremism and radicalism. Their real intent appears to be aimed at eliminating collective memory and cultural identity.

The Chinese government’s use of this new form of eliticide might suggest genocidal intent in its attempt to destroy the cultural structures of the Uyghur people.

The legal basis of the allegations against Uyghur and other elites of inciting extremist ideas appears nonexistent. The Chinese state has yet to provide any compelling evidence that a single elite has adopted radical views in opposition to the political and social status quo in the region, or that any of them has supported the use of violence to achieve a political objective. Uyghur and other elites are well-trained professionals, as well as innovators and cultural guardians. The party-state is “re-educating them” not because they need re-education but because the party-state wants to destroy their influence and, by extension, the peoples themselves.

The Chinese government’s use of this new form of eliticide might suggest genocidal intent in its attempt to destroy the cultural structures of the Uyghur people. In evaluating and compiling available data on the mass disappearance of Uyghur elites, this report both sets forth evidence toward that conclusion and demands justice and accountability for victims and their families.

VII. Recommendations

Based on the findings of this report, we recommend that democratic states, international organizations, and the global academic community take the following steps to respond to China’s unlawful detention, imprisonment, and disappearance of Uyghur and other Turkic Muslim elites:

To the Chinese Government

- Provide information on the status of the individuals listed in the database accompanying this report;

- Release all Uyghur and other elites arbitrarily detained and imprisoned; and

- Take immediate steps to end human rights violations against Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslim peoples, including arbitrary detention and imprisonment, forced sterilization, sexual violence, forced labor, cultural destruction, and restrictions on freedom of religion, cultural expression, privacy, and movement.

To the United Nations

- The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights should promptly release findings of her Office’s assessment of the situation in East Turkistan and determine next steps for accountability;

- UN Member States should immediately support a UN Commission of Inquiry within the Human Rights Council or General Assembly to elaborate on its findings and determine next steps for accountability;

- The Working Groups on Arbitrary Detention and Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances should contact the Chinese government and request information on the individuals detained or disappeared listed in the present report; and

- The UN should engage in additional cross-agency, multilateral action to press for accountability for disappearances, and arbitrary detention and imprisonment.

To the global academic community

- Examine academic and institutional partnerships with all Chinese entities to ensure none are connected to human rights abuses in East Turkistan;

- End scholarly exchange and cooperation with entities connected to human rights abuses in East Turkistan, and with all state institutions in China; and

- Universities should press the Chinese government for proof of life, and the immediate release, of detained Uyghur scholars and students, with a special focus on individuals who have obtained degrees, conducted research, or given lectures at their institutions.

FEATURED VIDEO

Atrocities Against Women in East Turkistan: Uyghur Women and Religious Persecution

Watch UHRP's event marking International Women’s Day with a discussion highlighting ongoing atrocities against Uyghur and other Turkic women in East Turkistan.