A Uyghur Human Rights Project report researched and written by Mustafa Aksu, Dr. Elise Anderson, and Dr. Henryk Szadziewski. Read our press statement on the report here, and download the full report here.

I. Introduction

At the opening ceremony of the Beijing Winter Olympics in February 2022, the Organizing Committee chose two athletes to deliver the ceremonial flame. One of them was Uyghur. Media across the globe reported the athlete’s name as Dinigeer Yilamujiang, much to the dismay of Uyghurs and researchers familiar with the Uyghur language. Dinigeer Yilamujiang is a Pinyin (Latinized standard Mandarin Chinese) rendering of the Uyghur name Dilnigar Ilhamjan. Among the publications using the Pinyin version were leading media outlets, including The Washington Post, The New York Times, and The Wall Street Journal.

The issue over names is consequential. The overseas media’s use of Dilnigar’s name in Pinyin was not intended to cause offense; however, the Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP), given the increased prominence and frequency of writing on Uyghurs, requests journalists, academics, as well as governmental and non-governmental researchers to use Uyghur versions of names.

This briefing outlines UHRP’s own guide to rendering the Uyghur language into Latin script, reporting Uyghur personal names, and writing Uyghur versions of geographical locations. This guide is not intended to exclude other Uyghur-directed interpretations; nevertheless, it is intended to respond to the Chinese government’s well-documented erasure of Uyghur language use in public life.1Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Resisting Chinese Linguistic Imperialism: Abduweli Ayup and the Movement for Uyghur Mother Tongue-Based Education,” May 16, 2019, https://uhrp.org/report/resisting-chinese-linguistic-imperialism-abduweli-ayup-and-movement-uyghur-mother/; Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Assault on the Uyghur Language in East Turkestan,” January 7, 2019, https://uhrp.org/report/briefing-assault-uyghur-language-east-turkestan/; Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Uyghur Voices on Education: China’s Assimilative ‘Bilingual Education’ Policy in East Turkestan,” May 20, 2015, https://uhrp.org/report/uhrp-releases-report-bilingual-education-east-turkestan-uyghur-voices-education-html/; Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Trapped in a Virtual Cage: Chinese State Repression of Uyghurs Online,” June 16, 2014, https://uhrp.org/report/trapped-virtual-cage-chinese-state-repression-uyghurs-online-html/.

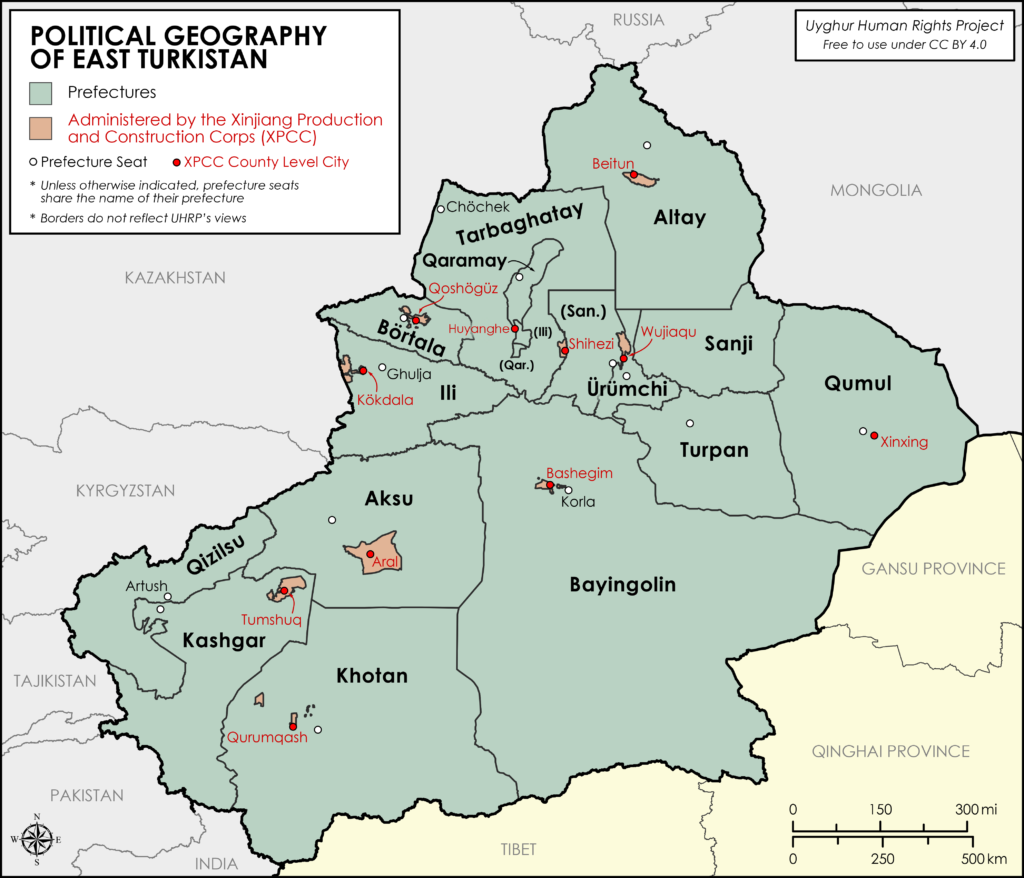

Furthermore, this briefing is also a call to decolonize language in discussions of Uyghurs. The Chinese government has explicitly linked use of the regional toponym of “East Turkistan” to extremism. UHRP recommends researchers reconsider using the term “Xinjiang,” meaning “new frontier” and to refer to the region with an alternative toponym. “Xinjiang” reinforces the colonization of Uyghurs. In addition to “Uyghur Region,” many Uyghurs also refer to their homeland as “East Turkistan.” Use of Uyghur and Turkic versions for geographical locations recognizes the language and owners of the land before the imposition of the Chinese Communist Party administration in 1949. For example, regular use of the Chinese name “Hami” for the city of “Qumul” has similar colonial associations for Uyghurs. In this briefing, UHRP does nevertheless recommend use of toponyms that have become established in English language reporting on East Turkistan, including “Kashgar,” for example.

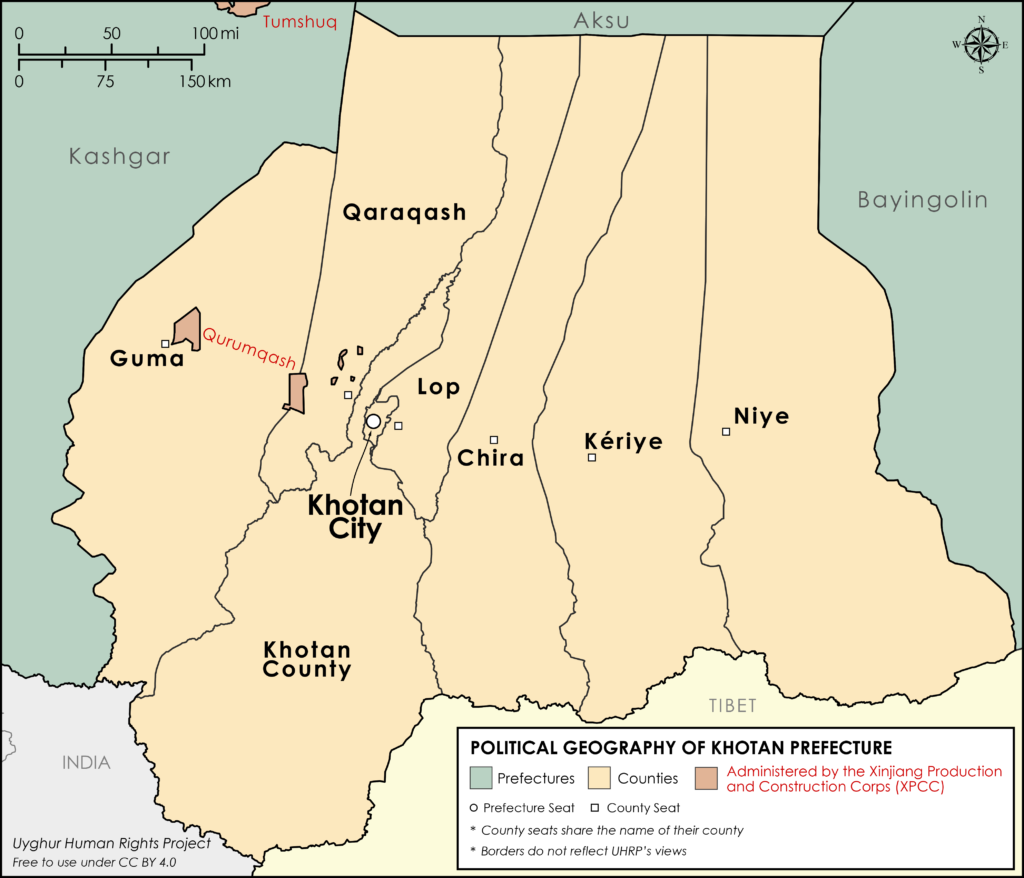

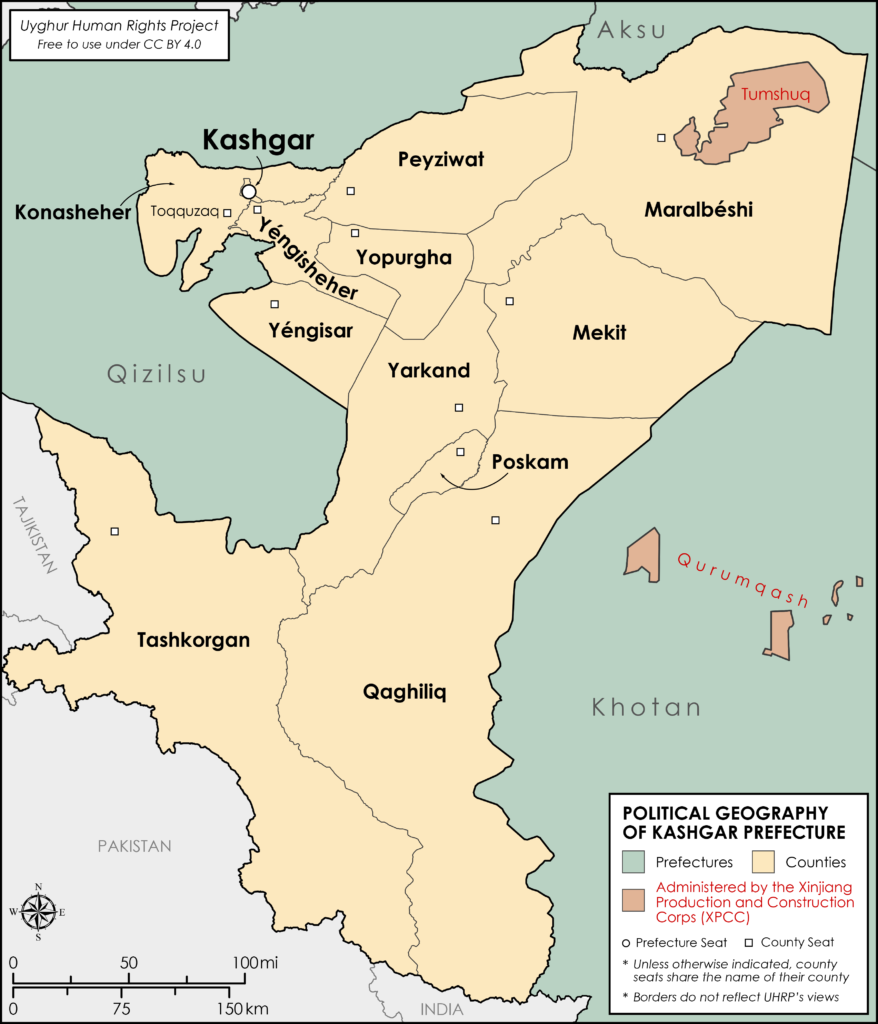

In sharing suggested nomenclature for sub-regional administrative spaces, UHRP is not making a statement on the validity of Chinese government-drawn prefectural and county divisions in East Turkistan. These administrative spaces have become integrated into how researchers discuss localities in the region. It is UHRP’s opinion, that as a Uyghur-led organization, we have a responsibility to ensure that these administrative units are at least named in Uyghur. In addition, we believe there is a scarcity of public domain maps that consistently provide Uyghur toponyms of political and physical geography. All maps available in this briefing are therefore being placed in the public domain and reflect UHRP’s recommended language.

Our guiding Latinized version of Uyghur is ULY, or Uyghur Latin Yéziqi. This decision too does not endorse one Latinization system over another and merely reflects what UHRP considers the orthography most frequently used by researchers.

Since the intensification of repression in East Turkistan in 2017, UHRP and many other entities have successfully lobbied several media outlets to change the spelling of the “Uyghur” ethnonym from “Uighur” in internal style guides. Similarly, we recommend editors consider using the versions of Latinization and proper nouns suggested in this briefing.

II. Transliteration in Latin Script

The following chart lays out four renderings of the alphabet used for the Uyghur language, three in Latin script and one in the modified Perso-Arabic script used for the Uyghur language in East Turkistan since the 1980s.

- Column 1 denotes a Latinized version of the Uyghur language preferred by UHRP, which is based on—but departs slightly from—Uyghur Latin Yéziqi (ULY), a transliterated alphabet created and published by the XUAR Nationality Languages and Scripts Working Committee2The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Nationality Languages and Scripts Working Committee is a government department tasked with administering language policy in the Uyghur Region, including drafting legislation on language use, overseeing the implementation of “bilingual” education, promoting the popularization of Mandarin, and preparing official translations into and out of Mandarin. in 2004.

- Column 2 shows Uyghur Latin Yéziqi (ULY), the transliterated alphabet created and published by the XUAR Nationality Languages and Scripts Working Committee in 2004.

- Column 3 shows the equivalents from the Pinyin-style system of transliteration often used for Uyghur in East Turkistan and across the People’s Republic of China. This standard informs the basis for state media, the State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China Press, etc.

- Column 4 provides equivalent letters in what Uyghurs call “Old Script” (kona yéziq), the Perso-Arabic script.

| UHRP | ULY | Pinyin Equivalent | “Old Script” |

| a | a | a | ئا |

| e | e | e | ئە |

| b | b | b | ب |

| p | p | p | پ |

| t | t | t | ت |

| j | j | j | ج |

| ch | ch | q | چ |

| kh | x | h | خ |

| d | d | d | د |

| r | r | r | ر |

| z | z | z | ز |

| j | zh | zh | ژ |

| s | s | s | س |

| sh | sh | x | ش |

| gh | gh | g | غ |

| f | f | f | ف |

| q | q | k | ق |

| k | k | k | ك |

| g | g | g | گ |

| ng | ng | ng | ڭ |

| l | l | l | ل |

| m | m | m | م |

| n | n | n | ن |

| h | h | h | ھ |

| o | o | o | ئو |

| u | u | u | ئۇ |

| ö | ö | o | ئۆ |

| ü | ü | u | ئۈ |

| w | w | w | ۋ |

| é | ë | e, i | ئې |

| i | i | i | ئى |

| y | y | y | ي |

UHRP makes a number of exceptions to our favored transliteration for names and words from the Uyghur language, including:

- Toponyms, where we often default to standard transliterations—e.g., “Kashgar” instead of “Qeshqer” (but “Ürümchi” instead of “Urumqi”). See section on Toponyms for further discussion.

- Personal names, where we default to personal preference of the person named, to the best of our ability. We describe considerations for personal names in more detail below.

III. Personal Names

Personal names can cause confusion for English-speaking readers unfamiliar with Uyghur naming conventions and the politicization of personal names in the PRC.

Uyghur naming conventions operate on the following key principles:

- Order: Given names come first, followed by the patronymic or family name. Note that Chinese naming conventions use a reverse order (family name followed by given name), which often results in confusion.

- Last names: Many Uyghurs do not use a family name as their last name, but instead a patronymic (i.e., their father’s first name). Some Uyghurs, particularly in the diaspora, do use family names, however.

- Multiple versions of names: Uyghurs often have at least three versions of their name, the first of which is the version they are given in the Uyghur language and script, the second of which is a transliteration of their name into Chinese characters, and the third (and/or fourth) of which might be a transliteration of their Uyghur and/or Chinese names into a Latin script.

- Subsequent reference using given names: Uyghurs generally do not refer to people as “Mr. Last Name” or “Ms. Last Name” but instead as “Mr. First Name” or “Ms. First Name.”

In general, UHRP recommends that journalists, researchers, and others writing about Uyghurs adopt the following practice when referencing Uyghur names: When possible, just ask.

Below are some detailed explanations and examples to keep in mind.

Issue 1: Given vs. “Official” Name

Most Uyghurs’ official documents, including passports and government-issued ID cards, use a Pinyin transliteration of the Chinese transliteration of their given names in the Uyghur language. However, Pinyin versions of Uyghur names often render the names very differently from their Uyghur originals. In many cases, Uyghurs’ first names and last names are even printed in reverse order on their passports. For example, detained Uyghur scholar Küresh Tahir’s name in Pinyin transliteration ought to be “Kurexi Tayier,” which retains the proper order of first name and last name. On a passport, however, his name would be rendered “Tayier Kurexi.”

A recent and prominent example of this phenomenon is the case of Dilnigar Ilhamjan دىلنىگار ئىلھامجان, the Uyghur skier who was selected to light the torch in the opening ceremony of the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing. The Pinyin version of Dilnigar’s Chinese name, Dinigeer Yilamujiang, was used widely in the international press about her involvement in the Olympics:

Name in Pinyin: Dinigeer Yilamujiang

Name in ULY: Dilnigar Ilhamjan

In rare instances, some Uyghurs prefer to use the Chinese version of their name over the ULY (or other Latinized) version. A seemingly similar, yet more complicated situation, is that of some Uyghurs who have become publicly known by the Chinese version of their name. Instead of the personal preference for a Uyghur language rendering of their name, some individuals have had the Chinese version normalized in global discourse. A prominent example of this is Wu’er Kaixi, the dissident who has been living in exile since his leadership in the student democracy movement in Beijing in 1989:

Name in Pinyin: Wu’er Kaixi

Name in ULY: Örkesh

The vast majority of Uyghurs, however, prefer Latinized versions of their names in ULY or similar alphabets, although spelling can vary widely based on individual preference (described in more detail below).

Recommendation: When interviewing and/or writing about a Uyghur individual, use due diligence to ensure you are using that person’s preferred version (i.e., official or given) and spelling.

Issue 2: Spelling

The spelling of the same name can differ widely depending on the particular Latin-script alphabet preferred by an individual. Take the name ئەزىز, which might be rendered “Eziz” (according to ULY) or, more commonly, as “Aziz” (according to the preference of most Uyghurs, who don’t always distinguish between front and back ‘a’ letters in Latin-script transliteration).

In general, writers should defer to personal preference for spelling, or perhaps to conventions already circulating in publicly available press and other writing.

The example of Erkin Tuniyaz, an ethnic Uyghur and government official, is instructive in this matter. “Erkin Tuniyaz” is the ULY transliteration of the Uyghur-script version of this individual’s name. However, he has been referred to with at least two other spellings:

Erken Tuniyaz

Alken Tuniaz

An unfortunate effect of these different spellings is that non-expert readers and other watchers of the situation have a difficult time realizing that different news articles are referring to the same individual. In the case of Mr. Erkin Tuniyaz, the different renderings of his name meant that many observers did not immediately recognize that he was both 1. the individual who had claimed in 2019 that all Uyghurs had been released from camp facilities and 2. the individual who delivered a speech to the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention.

On at least one occasion, China’s State Council Information Office appears to have supplied inconsistent and/or alternate spellings of Uyghur officials’ names to members of the international press, causing some of the confusion outlined here.

Recommendation: Consult experts wherever possible to clarify spellings. Where it is style or policy to default to “official” versions of names supplied by the SCIO or other PRC government bodies, use due diligence to also provide alternate renderings/spellings of personal names.

Issue 3: Last names/family names/patronymics

Most Uyghurs use patronymics—i.e., their father’s given name—for what is commonly called the “last name” in English. Use of the patronymic means that multiple generations in the same Uyghur family generally do not share a last name: husbands and wives continue to use their own patronymics after marriage, and they give their children the husband’s first name as a patronymic. Generally speaking, it is only the siblings in a nuclear family who share the same last name. Here’s what this might look like for a hypothetical Uyghur family:

Husband: Memet Abduqadir

Wife: Amangül Niyaz

Children: Arafat Memet, Arfiya Memet

As an outgrowth of this custom, Uyghurs do not often refer to other Uyghurs by their last names (because these last names are fathers’ given names). Where many English speakers might refer to Dr. Rahile Dawut as “Dr. Dawut,” for example, Uyghurs instead say “Dr. Rahile,” because “Dawut” is Dr. Rahile’s father’s name, not an intergenerational family name.

There are some notable exceptions to the convention of patronyms. A number of Uyghurs, particularly in Central Asia and elsewhere in the diaspora, have adopted family names that pass from one generation to another. Nury Turkel and Tahir Hamut Izgil are two examples, where “Turkel” and “Izgil” are family names in the sense similar to a “surname” broadly used elsewhere in the world. In cases such as these, we find it appropriate to refer to Nury Turkel as “Mr. Turkel” and to Tahir Hamut Izgil as “Mr. Izgil.”

Recommendation: Once again, when in doubt, ask questions to clarify. Take care when tempted to refer to a Uyghur by their last name alone in reporting or other writing and ask the individual what their preference is if possible. The New York Times set a good example in their reporting by asking UHRP staff member Mustafa Aksu his preference in a piece where he featured prominently. As a result, the NYT referred to him as “Mr. Mustafa” on subsequent reference; the same article refers to other Uyghurs using a different convention, presumably checked with them.

IV. Toponyms

A. Political Geography: Prefecture Level

Some Uyghur landscapes are given Chinese names in East Turkistan. Most of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC) county level cities are almost exclusively Han Chinese settlements and these cities are named in Chinese. Therefore, UHRP is using Pinyin spelling of those cities to emphasize the imposition of colonial Chinese placenames on a Uyghur landscape.

In the following tables, UHRP suggests toponyms to describe (a) the regional political geography, (b) the regional physical geography, (c) the political geography of Kashgar Prefecture, and (d) the political geography of Khotan Prefecture. In Section V, we present four free-to-use maps illustrating each of these spaces.

| Administrative Unit | Seat |

| Prefecture level cities | |

| Ürümchi | n/a |

| Qaramay | n/a |

| Turpan | n/a |

| Qumul | n/a |

| Autonomous prefectures | |

| Sanji | Sanji |

| Börtala | Börtala |

| Bayingolin | Korla |

| Ili | Ghulja |

| Qizilsu | Artush |

| Prefectures | |

| Aksu | Aksu |

| Kashgar | Kashgar |

| Khotan | Khotan |

| Tarbaghatay | Chöchek |

| Altay | Altay |

| XPCC county level cities | |

| Shihezi | n/a |

| Aral | n/a |

| Tumshuq | n/a |

| Wujiaqu | n/a |

| Beitun | n/a |

| Bashegim | n/a |

| Qoshögüz | n/a |

| Kökdala | n/a |

| Qurumqash | n/a |

| Huyanghe | n/a |

| Xinxing | n/a |

B. Political Geography: County Level

| KASHGAR PREFECTURE | |

| Administrative Unit | Seat |

| County level cities | |

| Kashgar | Kashgar |

| Counties | |

| Konasheher | Toqquzaq |

| Yéngisheher | Yéngisheher |

| Yéngisar | Yéngisar |

| Poskam | Poskam |

| Yarkand | Yarkand |

| Qaghiliq | Qaghiliq |

| Mekit | Mekit |

| Yopurgha | Yopurgha |

| Peyziwat | Peyziwat |

| Maralbéshi | Maralbéshi |

| Autonomous counties | |

| Tashkorgan | Tashkorgan |

| KHOTAN PREFECTURE | |

| Administrative Unit | Seat |

| County level cities | |

| Khotan City | Khotan |

| Counties | |

| Khotan County | n/a |

| Qaraqash | Qaraqash |

| Guma | Guma |

| Lop | Lop |

| Chira | Chira |

| Kériye | Kériye |

| Niye | Niye |

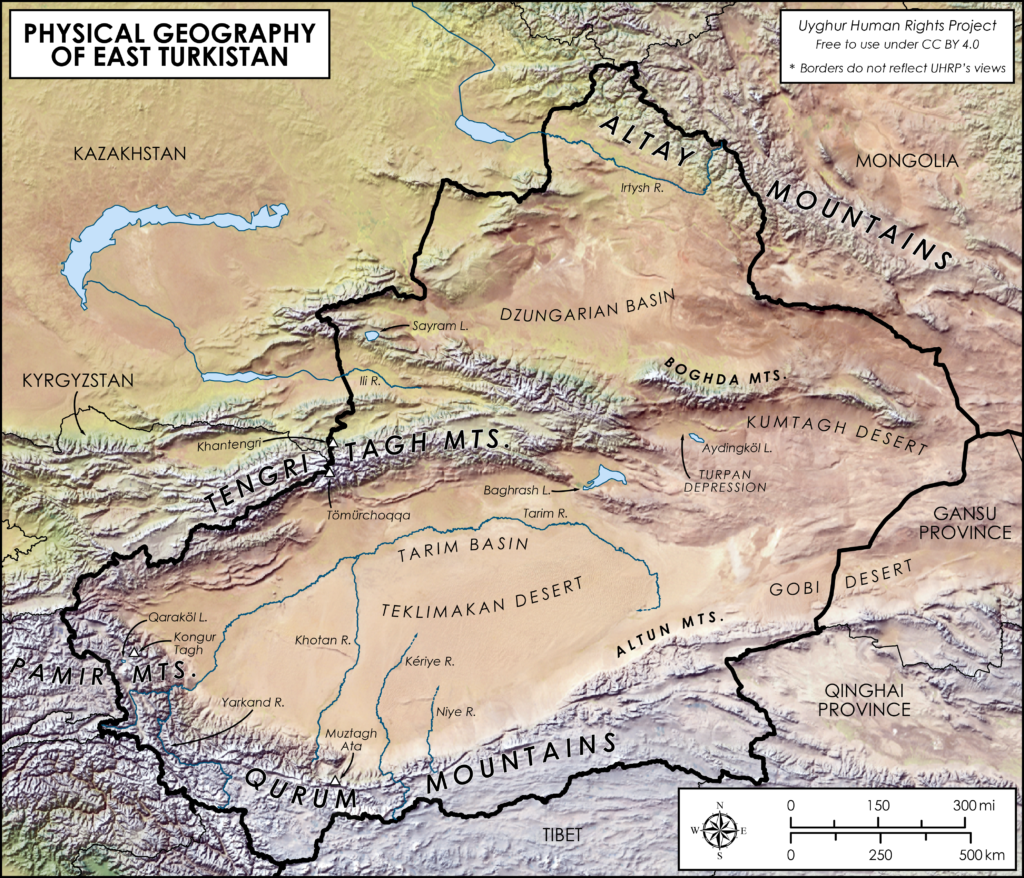

C. Physical Geography

| Lakes | Rivers | Basins |

| Baghrash | Tarim | Tarim |

| Aydingköl | Yarkand | Dzungarian |

| Sayram | Kériye | Turpan |

| Bughda | Niye | |

| Qaraköl | Ili | |

| Irtysh | ||

| Khotan | ||

| Mountain ranges | Mountains | Deserts |

| Tengri Tagh | Muztagh Ata | Teklimakan |

| Boghda | Kongur Tagh | Gobi |

| Altay | Tömürchoqqa | Kumtagh |

| Qurum | Khantengri | |

| Altun | Tengri Tagh | |

| Pamir |

V. Maps

About the Authors

This briefing was researched and written by Mustafa Aksu, Dr. Elise Anderson, and Dr. Henryk Szadziewski.

Mustafa Aksu is a program manager at the Uyghur Human Rights Project, and a 2021-2022 fellow in the Eurasia Foundation Young Professionals Network. Dr. Elise Anderson was senior program officer for research and advocacy at the Uyghur Human Rights Project until May 2022. Dr. Henryk Szadziewski is director of research at the Uyghur Human Rights Project.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Anonymous of a university in the United States, Eset Sulaiman of Radio Free Asia, Dr. Gülnar Eziz of Harvard University, and Dr. Eric Schluessel of The George Washington University for sharing their expertise and offering constructive feedback. The authors also thank Omer Kanat, Peter Irwin, and Ben Carrdus for reviewing this work and for providing advice on research design and data presentation. We also extend our appreciation to Gabe Moss of The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who made the maps for this briefing.

Cover design by Gabe Moss.

FEATURED VIDEO

Atrocities Against Women in East Turkistan: Uyghur Women and Religious Persecution

Watch UHRP's event marking International Women’s Day with a discussion highlighting ongoing atrocities against Uyghur and other Turkic women in East Turkistan.