A Uyghur Human Rights Project report by Henryk Szadziewski. Read our press statement on the report here, and download the full report here.

- 386 known cases of intellectuals interned, disappeared, or imprisoned, including 101 students and 285 scholars, artists, and journalists;

- The devastation of not knowing what has happened to loved ones is related in the testimonies of relatives. These family members living overseas have little, if any, information about the wellbeing or whereabouts of their close relatives;

- Experienced analysts express alarm over the future facing Uyghur intellectual life; and

- The systematic persecution of Uyghur producers of knowledge and culture must lead to action by academic, professional, and artistic institutions. It is time to end business as usual.

I. Summary

Since early 2017, the Chinese government has conducted a massive policy of disappearance, massinternment, and imprisonment of Uyghur people. Experts have estimated the number of Uyghurs interned in camps at between 800,000 and possibly over two million, making the internment campaign the most extensive since the second World War. In March 2019, researcher Adrian Zenz estimated the number of Uyghurs and Turkic people interned at 1.5 million.1Nebehay, S. (2019). 1.5 million Muslims could be detained in China’s Xinjiang: academic. [online] Reuters. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-xinjiang-rights/1-5-million-muslims-could-be-detained-in-chinas-xinjiang-academicidUSKCN1QU2MQ [Accessed 3 Mar. 2019]. The reports of survivors emerging from the camps are an alarming catalog of crimes against humanity, including torture and deaths in custody. Incessant political indoctrination and denial of Uyghur ethnic identity is part of the daily routine in these facilities.

As part of this campaign of repression, the Chinese government has targeted Uyghur intellectuals, defined in this report as university lecturers, professionals, teachers, journalists, students, artists, and other public or prominent individuals.

This report documents 386 known cases of intellectuals interned, disappeared, or imprisoned since 2017, including 101 students and 285 scholars, artists, and journalists. This report is the third UHRP has published on the persecution of the Uyghur intellectuals. The first was published on October 22, 2018 and the second on January 28, 2019. With each report, the known number of impacted intellectuals has risen from 231 to 386. Of the 386, only four are known to have been released. At Xinjiang University alone, 21 Uyghur faculty and employees have been affected. UHRP wished to acknowledge the work of Uyghur scholar Abduweli Ayup, the leading researcher on revealing the extent of internment, imprisonment, and disappearance of Uyghur intellectuals.

This report highlights the human dimensions of the Chinese authorities’ repression of Uyghur intellectuals and is divided into three main sections. The first documents the disappeared. The second relates the stories of the relatives of the disappeared and the third section shares the insights of Uyghur intellectuals and international experts, as to the motivations and impact of the persecution.

II. Implications

The systematic persecution of Uyghur producers of knowledge and culture must lead to action by academic, professional, and artistic institutions. The question remains: At a time when the state has thrown at least 386 scholars and students into ethnic-concentration camps, can exchanges and scholarly cooperation with state institutions in China continue?

The devastation of not knowing what has happened to loved ones is related in the testimonies of relatives. These family members living overseas have little, if any, information about the well-being or whereabouts of their close relatives. Their accounts reveal the psychological impact of this information void, as well as the determined resilience of individuals willing to speak out despite the power of the Chinese state. These voices merely demand information about their family members. A request the Chinese government denies. The refusal to meet this request illustrates the extent to which the Chinese authorities are willing to go to conceal the campaign of mass-internment.

Experienced analysts express alarm over the future facing Uyghur intellectual life. The repression of Uyghur-defined identity and production of knowledge means the logic of the Chinese government’s campaign is geared toward the full assimilation of the Uyghur people into Han culture. However, the aim is to not achieve this through a gradual policy of settling the Uyghur homeland, it is to reach this goal through accelerated measures which should cause shock and alarm.

The denial of the Uyghurs’ fundamental human rights, whether political, economic, social or cultural, has been government policy for many years. ‘Strike hard’ campaigns, so-called ‘bilingual’ education, ‘deextremification,’ and ‘Western Development’ represent varying dimensions to the ongoing repression in the Uyghur homeland. Rights groups have highlighted the need to address these issues before the situation becomes critical. That time has been reached and it is now the full responsibility of governments, multilateral institutions, and in the case of Uyghur intellectuals, universities and other academic entities, to hold China to account. It is time to end business as usual.

III. The Disappeared

This report highlights seven individuals whose relatives overseas are speaking up despite the heavy intimidation of the Chinese government against Uyghurs in exile. Those speaking up are Bahram Sintash, a graphic designer living in Washington, DC; Gülziye Taschmamat, a software engineer now in Germany; Arslan Hidayat, a teacher residing in Istanbul; Tahir Mutällip Qahiri, a PhD student at the University of Göttingen; “Aygul,” currently in Europe; and Alfred Uyghur, a student in the United States. These are just some among many Uyghurs and Kazakhs in exile and in the diaspora, who are speaking about their detained loved ones, including many intellectuals.2Sintash, B. (2019). China is trying to destroy Uighur culture. We’re trying to save it. [online] Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2019/03/18/china-is-trying-destroy-uighur-culture-were-trying-saveit/?utm_term=.737fea727523 [Accessed 20 Mar. 2019]; Abbas, R. (2018). My aunt and sister in China have vanished. Are they being punished for my activism? [online] Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/democracypost/wp/2018/10/19/my-aunt-and-sister-in-china-have-vanished-are-they-being-punished-for-myactivism/?utm_term=.82df199daa95 [Accessed 20 Mar. 2019] and Yang, William. (2019). #MeTooUyghur: The Mystery of a Uyghur Musician Triggers an Online Campaign. [online] TheNewsLens. Available at: https://international.thenewslens.com/article/113718 [Accessed 20 Mar. 2019].The Chinese government uses threats and intimidation towards Uyghurs overseas to impose silence about conditions in the Uyghur homeland.3uhrp.org. (2019). The Fifth Poison: the Harassment of Uyghurs Overseas. [online] Uyghur Human Rights Project. Available at: https://uhrp.org/press-release/fifth-poison-harassment-uyghurs-overseas.html [Accessed 12 Mar. 2019] and The Atlantic. (2018). China is Surveilling and Threatening Uighurs in the U.S. [online] The Atlantic. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UtYyAP67k60 [Accessed 20 Mar. 2019].

For this updated report on Uyghur intellectuals, UHRP has collected information from several sources. The work of Uyghur scholar-in-exile Abduweli Ayup has been critical in alerting the international community to the extent of the devastation inflicted on Uyghur intellectual life. UHRP is indebted to his research in compiling this work.

Verifying the names of impacted Uyghur intellectuals is not a straightforward task given the tight control of information in East Turkestan. Information on Uyghur intellectuals has been checked with sources from the Uyghur exile community, relatives, and the overseas media, including the exceptional journalism of Radio Free Asia’s Uyghur Service. Given the severe reporting restrictions in place in East Turkestan, UHRP welcomes corrections to the list of Uyghur intellectuals presented in the appendix.

Those taken away include 101 students identified as interned, imprisoned or forcibly disappeared and 285 scholars, artists, and journalists: a total of 386 individuals. Among them are 77 university instructors and 58 journalists, editors, and publishers. (See Table 1). In December 2018, the Committee to Protect Journalists noted that of the 47 journalists known to be imprisoned throughout China, 23 are Uyghur.4Committee to Protect Journalists. (2018). 47 Journalists Imprisoned in China. [online] Available at: https://cpj.org/data/imprisoned/2018/?status=Imprisoned&cc_fips%5B%5D=CH&start_year=2018&end_year=2018&group_by=location [Accessed 12 Mar. 2019]. 280 of the intellectuals are male, 70 female and 36 of unknown gender, given incomplete data. (See Table 2).

Short biographies of some of those detained and disappeared can be found in UHRP’s October 2018 and January 2019 reports, including:

- Rahile Dawut: A leading expert on Uyghur folklore and traditions at Xinjiang University whose work the Chinese state had sponsored. She left Urumchi for Beijing in December 2017 and has not been heard from since.

- Chimengul Awut: A poet who was reported interned in a camp in November 2018. Chimengul was celebrated at the regional Women’s Literature Conference in 2004 and her poem The Road of No Return won the Tulpar Literature Award in November 2008.

- Abdulqadir Jalaleddin: A professor, philosopher, and poet at Xinjiang Normal University.

- Tashpolat Tiyip: The former president of Xinjiang University, who was sentenced to death with two-year reprieve on “separatism” charges.

| Students | 101 |

| University instructors | 77 |

| Journalists, editors & publishers | 58 |

| Poets, writers & scholars | 35 |

| High school & middle school teachers | 27 |

| Actors, directors, hosts & singers | 23 |

| Medical researchers and doctors | 20 |

| Computer engineers | 15 |

| Other | 22 |

| Photographers & painters | 8 |

| TOTAL | 386 |

| Female | 70 |

| Male | 280 |

| Unknown5Some reports of interned or imprisoned intellectuals have been collective and the gender not specified | 36 |

| TOTAL | 386 |

Xinjiang University faculty have been a focus for the Chinese authorities, given their prominence in Uyghur-produced scholarship conducted in the region. Twenty-one Uyghur intellectuals have been interned from the institution, including internationally-recognized professors such as Dr. Abdukerim Rahman.6Anderson, A. and Byler, D. (2018). How is Abdukerim Rahman surviving without his books?. [online] art of life in chinese central asia. Available at: https://livingotherwise.com/2018/10/02/abdukerim-rahmansurviving-without-books/ [Accessed 11 Oct. 2018].

Fifteen staff members from Xinjiang Normal University, including Professor Yunus Ebeydulla, 13 from Kashgar University, including Professors Mukhter Abdughopur and Qurban Osman, six from Xinjiang Medical University, including Halmurat Ghopur and Abbas Es’et, six from the Xinjiang Social Sciences Academy, including Küresh Tahir and Abdurazaq Sayim, and four from Hotan Teachers College, including Ömerjan Nuri and Juret Dolet, are also known to have been interned in camps, imprisoned, or forcibly disappeared.

In early July 2017, the Egyptian security services, at the behest of the Chinese government, began rounding up Uyghurs resident in Cairo, predominately students of Arabic and Islamic theology at Cairo’s Al-Azhar University. Twelve Uyghur students were forcibly returned on July 6, 2017 and another 22 Uyghurs’ deportations were pending at that time.7

Youssef, N. and Buckley, C. (2017). Egyptian Police Detain Uighurs and Deport Them to China.

[online] New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/06/world/asia/egypt-muslimsuighursdeportationsxinjiang-china.html [Accessed 29 Jun. 2018] Abduweli Ayup’s research has uncovered the names of 48 Uyghur students sent to internment camps after their enforced return to China from their studies at AlAzhar University.

The persecution of the staff of the few remaining Uyghur-language publishing outlets and governmentrun research institutes is clear evidence of the campaign to eradicate learning and scholarship in the Uyghur language. At least 20 Uyghur employees of Xinjiang Educational Press, five members of the Xinjiang Gazette’s Uyghur Editorial Department, and 13 current and former employees of Kashgar Uyghur Press, representing the current and past leadership, have been interned or otherwise punished. A further four employees at the regional language committee, nine individuals at Xinjiang Television, and five performers at Xinjiang Theater are documented as interned or imprisoned.

The wholesale removal of experienced Uyghur media professionals, language researchers, and Uyghurlanguage performers is an extreme culmination of a decades-long campaign to systematically eradicate Uyghur language from public life,8Byler, D. (2019). The ‘patriotism’ of not speaking Uyghur. [online] SupChina. Available at: https://supchina.com/2019/01/02/the-patriotism-of-not-speaking-uyghur/ [Accessed 12 Mar. 2019]. which includes pressure on Uyghur as a medium of educational instruction and the decimation of Uyghur literature and history from the curriculum.9uhrp.org. (2015). Uyghur Voices on Education: China’s Assimilative ‘Bilingual Education’ Policy in East Turkestan. Uyghur Human Rights Project. [online] Available at: https://uhrp.org/press-release/uhrp-releases-report-bilingual-education-eastturkestan%E2%80%94uyghur-voices-education.html [Accessed 12 Mar. 2019].

In a January 2019 update on interned, imprisoned and disappeared intellectuals, UHRP reported that since 2017, five individuals are known to have died in custody or soon after their release. These individuals include religious scholars Muhammad Salih Hajim and Abdulnehed Mehsum; and students Abdusalam Mamat, Yasinjan, and Mutellip Nurmehmet. A sixth intellectual, Erkinjan Abdukerim, a teacher from Awat Township near Kashgar, died on September 30, 2018 shortly after his release from an internment camp.

The names compiled for this report are likely a small portion of those persecuted. Given conditions of extreme secrecy, and harsh punishment for anyone communicating unauthorized information to the outside world, the numbers of persecuted Uyghur intellectuals remains an illustrative rather than definitive accounting of the scope and scale of atrocities committed by state authorities. A full list of the 386 individuals is available in the Appendix to this report.

IV. The Voices of Family Members

The Uyghur Human Rights Project conducted interviews with exiled family members of seven of the intellectuals detained and disappeared. In these intimate interviews, they provide a portrait of their loved ones’ accomplishments and ideals giving voice to their experiences of indescribable suffering. These individuals are looking for a reason for why their relatives were taken, when there isn’t, and the pretexts are random. UHRP thanks them for providing these rich narratives and trusting UHRP with their stories.

One commonality among some of the testimonies deserves comment. Many overseas relatives of those detained carry feelings of guilt for their relatives’ treatment, express concern that their actions may have been the cause of their loved ones’ suffering, or at any rate are concerned to understand the reasons why their relatives have been taken away — even when they know that there is no possible justification for this kind of extralegal punishment. This sense of responsibility is yet another form of pressure and pain suffered by the families of intellectuals and others detained in the Uyghur homeland.

Bahram Sintash (about his father, Qurban Mahmut)

“I cannot confirm any details about my father, maybe he is in a camp, maybe he is jail. I don’t know. At the beginning of 2019, some Uyghurs were getting information about the release of their family members. I tried to contact my friends in Urumchi to see if there was an update. There wasn’t.

I’m here to raise my voice for my father. However, there are so many tragic Uyghur stories, so I’m also here to raise my voice for them. I’m a graphic designer, so I’m using my skills to expose the situation to the media or on social media. Back home, I studied graphic design. In the U.S., I own a business.

My father is a scholar and a writer. He’s a famous journalist too. I like to call him the ‘godfather’ of Uyghur journalism because he was editor in chief of the influential periodical ‘Xinjiang Civilization.’ Back in the early 80s, Uyghurs didn’t read magazines. They thought it was all propaganda. However, ‘Xinjiang Civilization’ asked difficult questions, such as: “What are our problems? How did we get here? What can we do?” The magazine was all about educating Uyghurs about themselves and it became very famous. It was publishing up to 10,000 copies in the late 1980s and by the late 1990s over 80,000. That’s a lot for a Uyghur language magazine. It was also independent with no state funding, just the money from subscribers. There was no internet then, so many influential people read it. Think of ‘Time’ magazine but for Uyghurs. It promoted Uyghur scholars, writers, artists and photographers.

All the time, the government was putting pressure on my Dad. He worked with a state censor and found ways of saying things without directly saying them. However, he was smart. He knew he couldn’t cross the line with the authorities and didn’t use sensitive words. In 35 years as Editor-in-Chief, he didn’t make a mistake.

In 2004, the Chinese government started up the bilingual education policy, which effectively meant Uyghur was not taught in schools. The government was changing the textbooks too. One writer in ‘Xinjiang Civilization’ argued it was better for Uyghurs to get an education in Uyghur, a position the government found a problem with. They wanted to meet the writer and my father joined the meeting knowing just what to say to keep the authorities from making a bigger deal of it.

My dad worked 14 hours a day on the magazine, editing works by all the famous Uyghur writers and working to help our people. Uyghurs needed to know about the world and China. He worked from the heart.

I started to worry about my dad in January 2018 because of reports on the disappearance of other intellectuals and editors. Between January and February, I took to reading and listening to Radio Free Asia. My mother and my sister had already blocked me from their social media, so I tried to get help from our neighbors back home. In February, one person told me, using code words, my dad had been taken to a camp somewhere in Urumchi. Then these neighbors started to block me. I got worried about the safety of my family in Urumchi. I had no one to contact. How would you feel hearing terrible things on the news every day without any way to find out what had happened to your family?

The Chinese government wants to erase us. In the 1980s they eased up and we found ways to be Uyghur again. In time, this became a threat to the government. People who are educated are a threat to such governments. As Uyghurs we should be proud and show no fear in our hearts. I now realize why Uyghurs wrote about culture and identity so much in the 80s. It was to educate the next generation to stand up and be counted as Uyghurs.”

Gülziye Taschmamat (about her sister, Gulgine Taschmamat)

“I’m from Ghulja. I studied software engineering at Shenzhen University from 2005 to 2010. In 2011, I went to Germany and was granted political asylum because I confronted some of my peers about the treatment of Uyghurs after the July 5, 2009 unrest in Urumchi.

My sister went to high school in Urumchi. She was a good student and had good enough scores in her exams so that she should be able to study what she wanted. She wanted to study French in Beijing and then go to France. It was her dream. However, in 2010, she was accepted to study at University of Technology Malaysia in Johor. She studied English at first and then enrolled in computer science and went on to complete her masters in December 2017. She was excited to go to Malaysia, thinking it could lead to an opportunity at a university in Europe.

At first, Gulgine went back to Ghulja in March 2017 because my father was sick. When she was there, the local police made her sign a statement saying that after she finished her classes in Malaysia, she would return to China. If she didn’t return, she’d lose all connection with her parents. The police were from the neighborhood. It was a direct threat. They said: ‘If you don’t come back, it will be dangerous for your father.’ My father was under a cloud of suspicion because he had sent money to me in Germany.

Also, the police collected blood samples from her and confiscated her passport for a month. We were also worried about my brother, a medical student, who might be taken to a camp. In October 2017, my parents told her to not come back from Malaysia. I also told her to not go back to China. I last spoke to Gulgine on December 26, 2017 through WhatsApp. She was at the airport in Kuala Lumpur. I learned in February 2018 that she had gone missing. I heard it through a friend. I asked this friend about my family on February 1. A week later she told me Gulgine had gone missing. We had a code to communicate. She told me Gulgine had ‘gone to study’ and that ‘no one knows when she will finish.’ She also told me not to ask any more questions and then she deleted me from social media.

The only reason I think she could have been taken away once she landed in China is because of her studies overseas. She was just a student and not political. She liked to study. I’ve asked German government officials to help. I get sympathy sometimes, sometimes I get no reply. I’ve also contacted her university seeking help. One professor replied and some of the students, especially of Chinese origin, think she might be a terrorist. They really don’t get it.

I haven’t been in contact with my parents since October 2017. My father is a trader and my mother is a homemaker. My friends in China have all deleted me on WeChat so I cannot get any information. I’ve tried to make contact through other means. In February 2018, a friend of a friend called my parents’ home and asked about Gulgine. My mother told them to never call again.

In mid-July to the beginning of August 2018, a German reporter visited Ghulja and tried to visit our home. From the outside, she saw my father, mother and brother inside the home and that is all she could do to confirm they are OK.”

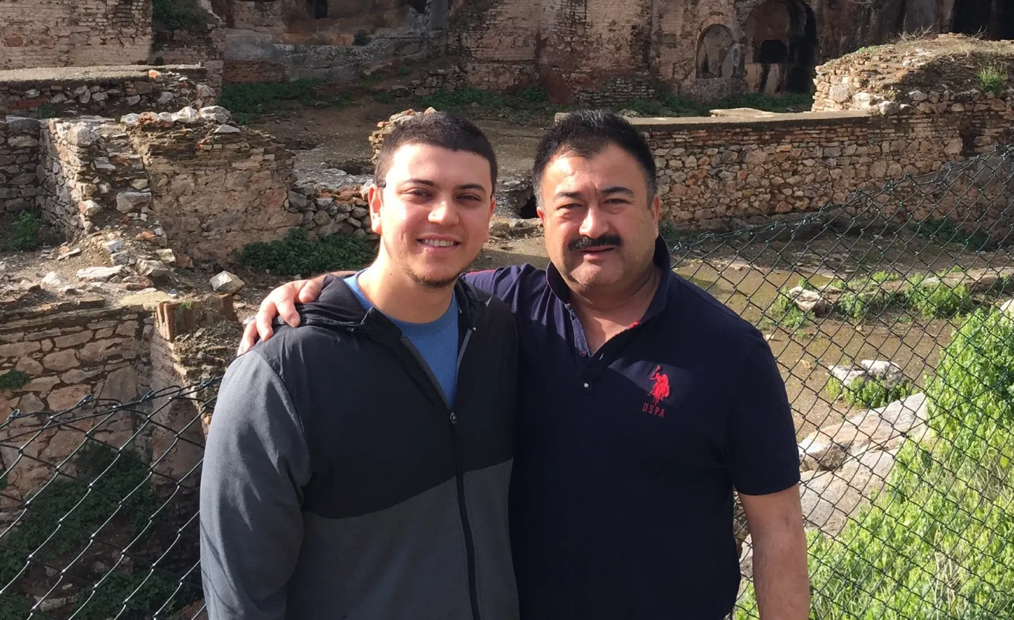

Arslan Hidayat (about his father-in-law, Adil Mijit)

“My name is Arslan. My parents left East Turkestan for Australia in 1983. I was born in Australia. I liked to play music as a kid, and I got a BA in music and a master’s in education. I’m qualified to teach in New South Wales. As children we used to go to East Turkestan every year for holidays. My wife’s parents and my parents were friends in East Turkestan. My wife and I were married 10 years ago. I worked as a music teacher in Australia, but my in-laws could get to Turkey easily, so my wife and I decided to move there in 2011 so she could see them. If we Uyghurs had a free country, it wouldn’t be like this. I now work as an English teacher in Istanbul and help with Uyghurs who want to go to university here. My in-laws would come to see us about two to three times a year for a few weeks at a time.

My father-in-law is the famous Uyghur comedian Adil Mijit. I had to go public about my father-in-law because he is such a well-known personality.

For the birth of our first daughter in 2016, my mother-in-law came to Turkey. She is still with us in Istanbul. Around this time, we started to hear artists at the Xinjiang Opera Troupe, where Adil was employed, were getting into trouble because of ‘underlying’ messages about religion in their work. My father-in-law used to go to the mosque to pray, so we were a bit concerned. In June 2017, he came to see us. We knew people were disappearing into camps, but he told us he would be OK. If I knew then what I know now, I would have ripped up his passport. On November 2, 2018, he disappeared.

We were able to connect for several months after we last saw him via WeChat. When we talked, we talked in code. Things were going well: ‘The weather is beautiful.’ Things weren’t going well: ‘The weather was stormy or cold.’ Sometimes he would drop out of contact and we feared the worst, but he would return and then tell us he had to undertake some propaganda work in the villages for the government. He also told us he had been in hospital for a couple of persistent conditions from about midAugust 2018. He was able to use his phone from the hospital, but said he was under pressure from work. In the last two months before his disappearance, his messages become more angry detailing how his boss was picking on him.

He performed at the October 1 National Day TV extravaganza in 2018. He was suspended from work in about mid-October. On November 1 and then again on November 2, we sent him photos and videos of his second granddaughter. There was no response. We waited for one month after he didn’t respond and called his workplace only to be told there was no information. Then we spoke to Radio Free Asia to say he had been cut off from us or disappeared.

We don’t know if he has had a trial. Someone contacted us to tell us he had received a prison sentence and wasn’t in a camp. We’ve also received a message from a person who said she was his nurse in a prison hospital.

I’m not sure what he could have done. He has pride in his work, saying it brought some happiness to Uyghurs; however, the current conditions have cut the hope for Uyghurs to zero. I’ve done what I can speaking to the overseas media, such as the BBC.

Comedians in China are not employed like those in the U.S. or other countries. They are attached to a work unit and have to participate in government propaganda. My father-in-law’s disappearance is the death of laughter for Uyghurs. In one of his last communications with us he said, ‘I am prepared to be imprisoned. I want to be with my people. I am who I am because of them. I can’t leave them when they need me. The least I can do is give them some entertainment.’

His wife is busy with our kids. She never watched the news before, but now she watches everyday to see who else might have disappeared.”

Tahir Mutällip Qahiri (about his father, Mutällip Sidiq Qahiri)

“I found out about the disappearance of my father from a Radio Free Asia report on November 22, 2018. I was shocked. The last time I had spoken to my father was on October 18 by phone. At that time, he told me I shouldn’t call him again.

My father was born in 1950 in Yengisheher County near Kashgar. During the Cultural Revolution he was sent to a rural area, then took the university entrance exam in 1978 and gained his bachelor’s degree in 1983 in Chinese literature from Kashgar Teacher’s College [NOTE: this institution is now called Kashgar University]. He took a job at Kashgar Teacher’s College teaching literature, and modern Uyghur. In 1989, my father went to Cairo University to study Arab literature under government sponsorship. He returned in 1990, served in the university administration, was a deputy editor of an academic journal, and from 1993 was a full professor of literature. In 1995, he applied to study Arab literature again at Cairo University and was awarded a two-year scholarship. The university authorities would not let him go. The Party Committee denied his request.

In his later years, my father started to research language in the Kashgar and Hotan areas, especially the influences of Persian on usage. He also published a well-known work on Uyghur names in 1992, which he began in 1985. He published seven books on Uyghur names in total. In 2010, he produced his most extensive work on Uyghur names at over 900 pages in length. He also published 11 books in relation to the Arabic language and collated a Uyghur alphabet book for schools in 2011. In the 90s, he published a memoir describing his life in Egypt and his academic research on Uyghur names. He also worked as an editor for a number of journals not just focused on literature, but also natural sciences.

By 2017, his books had been banned. In May 2018, I learned he had been fined 68,000 Chinese Yuan for his research on Uyghur names. He also had his salary cut, but still kept his party membership. His arrest, probably in November 2018, came as a surprise, because I thought he had been punished already and his health is not so good. All my father was passionate about was his research. He had no other agenda.

I have no idea about his condition and his whereabouts – only what I know from Radio Free Asia. The accusations against him are that he spread Islam and promoted Arab culture. These accusations are false. When he went to Cairo, he was selected to go by the government. This has nothing to do with Islam. The Chinese government didn’t like him because I believe his research on Uyghur names did not please them. The news has destroyed our family. I find it difficult to sleep.

On January 9, 2019, I rang the offices at Kashgar University. The secretary’s office picked up the phone and we talked for ten minutes; however, they could not tell me anything. My father has five children, one in Urumchi, three in Kashgar, and me.” [NOTE: since this interview in January 2019, Mutällip Sidiq Qahiri received a ‘proof of life’ video from his father].10Van Brugen, I. (2019). Uyghur Diaspora Receive ‘Proof of Life’ Calls From the ‘Disappeared’ in Xinjiang. [online] Epoch Times. Available at: https://www.theepochtimes.com/uyghur-diaspora-receive-proof-of-life-calls-from-the-disappeared-inxinjiang_2828189.html [Accessed 13 Mar. 2019].

“Aygul” (about her sister, “Aynur”)

“My sister lived close to Hotan. I now live overseas. It wasn’t easy for me to get a passport, but I’m free now. The Chinese government gave me a lot of trouble when I was in China, but I cannot give the details. My sister has had some conflicts at her job mainly because she is religious. She got her education at a university outside of our region and is an expert teacher of mathematics. Her degree is in a different specialization than math, but she couldn’t get a job in that field. My sister also had a teaching diploma and a gift for numbers, so she became a teacher. There aren’t too many jobs for Uyghurs in our hometown. She really wanted to go overseas, but she settled down, married and had children.

I lost contact with most of my relatives in early 2017. Then, out of the blue, we were contacted. We got another communication two days later and this person told us we wouldn’t be able to contact each other again. I was told my sister was missing. My relatives have deleted me from WeChat. I don’t want to cause any trouble by contacting them, so I’m waiting for some news. I have no idea where anyone is, especially my sister. I’m not sure why being religious should be a problem. I can’t sleep very well, and I cry a lot. My family here says I don’t smile anymore.” [NOTE: identifying details have been changed to protect the interviewee].

Alfred Uyghur (about his mother, Gulnar Telet, and his father, Erkin Tursun)

“I came to the U.S. as a student, mostly because the situation back home was just getting worse. My parents were worried about me. I got to the U.S. in October 2015 after some trouble getting a passport. After my father and mother were detained towards the end of 2017 and my sources of funding had run out, I dropped out of school. The financial and other pressures are sometimes too hard to bear.

My father’s name is Erkin Tursun. He graduated from the history faculty at Xinjiang University and qualified as a history teacher. In the early 90s, he organized dances at schools and children’s events. This work got him employed at Ili TV. He hosted a TV show and opened a school of music, arts, dance and language for Uyghur kids. He also put on boxing competitions. However, in 2001, the authorities cancelled the boxing and music programs. He then directed a movie about the social problems facing Uyghurs, such as drug use and the high divorce rate.

In about 2002 or 2003, he went to Japan. At that time there was a lot of interest in Uyghur culture in Japan. He went on a cultural exchange program and even traveled on a diplomatic passport. His activities were not political at all. He continued working with Ili TV and also opened a restaurant in 2008. My mom, Gulnar Telet, was a mathematics teacher in Ghulja at Number 5 Elementary school. She has worked there since the 1990s.

Between 2015 and 2017, I called my parents regularly. As the situation got worse, the calls became less frequent. Over time their language changed. They didn’t use the greeting ‘Salaam’ anymore, and started to say, ‘Everything is OK, we are living a beautiful life thanks to the Communist Party, and our lives are getting better and better.’ Normal people don’t talk like this and certainly not my parents. We used code words sometimes if we wanted to talk about the true conditions. One day, they told me not to call, but to use social media to stay in touch. However, even that means of communication became sporadic. Eventually, they deleted me from their contacts.

I did get a message from a family friend who told me my mom had been in a camp since November or December 2017. I also received some information my mother may have been released, but I have no way of knowing if this is true or not. Is she in Ghulja? I don’t know. I lost contact with my dad in 2017 and didn’t find out he had been detained until August 2018. Someone said my father received a prison sentence of between 9 and 11 years. I have no idea on what charge. He might be in Xinyuan prison near Kanas.

Both my parents speak Chinese, so I have no idea what kind of training they would need. They are college graduates. My father was involved in cultural activities and I think they are arresting anyone who is doing this work. I don’t think his disappearance is due to his trip to Japan because it was government organized. There is no excuse for detaining my mom. I haven’t contacted my relatives as I don’t want to make any trouble for them.

Before I left for the U.S., my mom said she didn’t think she would see me again as I wouldn’t be able to come back. I promised her I wouldn’t go near any of the political activities organized by Uyghurs in exile in Washington, DC. I stayed away from them, kept quiet and caused no problems. I thought this strategy would work. However, since their disappearance, I’ve decided to speak out.”

V. The Analysts

UHRP asked Uyghur intellectuals in exile and scholars of Uyghurs to provide their analysis of two straightforward but fundamental questions about the persecution of Uyghur academics, artists, and public figures.

− Why is the Chinese government targeting Uyghur scholars, artists and other intellectuals?

− What are the long-term implications of targeting Uyghur intellectuals?

Three Uyghur intellectuals in exile, Rahima Mahmut, Tahir Hamut and Aziz Isa, graciously provided comments. Dr. Darren Byler, lecturer at the University of Washington, and Elise Anderson, PhD candidate at Indiana University also contributed thoughts on the two questions. Both have recent experience of visiting the Uyghur homeland and are academic specialist on different aspects of the Uyghur experience.

The responses from these scholars represent their personal opinions. Their comments help identify the causes and implications of the repression and amplify the urgent discussion among concerned thinkers about how to ensure the survival of Uyghur intellectual life in the face of wholesale cultural destruction and indescribable suffering in the Uyghur homeland.

Why is the Chinese government targeting Uyghur scholars, artists and other intellectuals?

Darren Byler: “Initially my research focused on visual contemporary arts. This scene first really began to emerge in the early 2000s when large-scale Han domestic tourism to the region began. Initially much of this art production focused on ethnic minority cultures and landscapes and was marketed toward the tourists. This began to slowly change in the mid to late 2000s when urban planners and artists began to discuss the development of a contemporary arts scene in Urumchi along the lines of similar arts scenes in Beijing and Shanghai. In 2009, a creative industries district was established in the city in decommissioned government buildings and in 2014 the Xinjiang Contemporary Art Museum was founded within the district.

Initially, this space was not that tightly regulated. A significant portion of the art featured in the district and museum, perhaps around 40 percent, was contemporary art that was not pitched toward the tourist or commercial market. Themes of marginalization, hybridity and urban malaise rose to the fore in an emerging Xinjiang school or style of contemporary art. Paintings and photography that commented elliptically on the political and economic situation in the region were at times displayed in group exhibitions. In general, though, these forms of political commentary were done with a great deal of care so as not to overstep the boundaries of what was permitted. Since the space was dominated by Mandarinspeaking artists and curators, many Uyghur artists had difficulty accessing this space, but minority artists who did feel comfortable operating in the Chinese world were frequently featured in exhibitions.

In 2017 and 2018, any potential for political and inter-ethnic solidarity dissipated. Uyghur artists are no longer included in exhibitions and the work that is now featured is either strongly influenced by state propaganda or is influenced by the tropes of exotic minorities that dominated the earlier ‘fine art’ period in the early 2000s.

So far, the disappearances of public figures have focused primarily on those who are working in speech or text-oriented mediums. There are a number of reasons for this. First, there are simply fewer Uyghur painters and photographers than there are those who work in other mediums such as poetry, fiction, film or music. Second, on a related note, the reeducation campaign specifically targets public figures who have significant influence. Since most Uyghur visual artists do not have significant followings in the Uyghur community they are not seen as potentially seditious as writers, filmmakers or musicians. Third, perhaps most importantly, one of the primary targets of the reeducation campaign is diminishing the value and use of Uyghur language. Since painting is a visual medium it is not placed under the same scrutiny as literature, film or music. Many Uyghur public figures who have disappeared into the detention system were taken because of texts they wrote with the approval of state censors in the past. These texts have now been criminalized.

Many Uyghurs refer to what is happening as worse than the Cultural Revolution. They say it is worse because of the way the state has used systems of surveillance to monitor their daily behavior and control their speech. In the past it was possible to find private spaces away from the gaze of the state. They also refer to the way many children have been taken away from their parents as an element that is worse than that period.”

Tahir Hamut: “The Chinese government has always targeted the Uyghur elite. But the situation is different in different periods. Starting from 2014, the target is related to the ‘One Belt One Road’ project of the Chinese leadership. There may also be some reasons we don’t know. Moreover, this attack on the Uyghur elite began with a review of Uyghur primary and secondary school textbooks and historical novels in Uyghur. The Chinese government has detained millions of Uyghurs, of whom the proportion of elites is relatively high. The Chinese government knows the strong influence of elites in Uyghur society. It would serve as a deterrent to other Uyghurs by targeting these people. Of course, the government found some reasons to target these people. The question is whether these reasons are legitimate; whether the process of detaining them is in accordance with legal procedures; and most importantly, why the Chinese government suddenly arrested so many people.”

Aziz Isa: “We can clearly see if we look at the decades-old policies of the Chinese government towards Uyghurs, they first started banning Uyghur-language schools and started attacking Uyghurs’ religious belief. From this point, we can see that their ultimate goal is to achieve a total forced assimilation of the Uyghurs, turning them into Han Chinese, by destroying all Uyghur ethnic and cultural identities, using all the might of state power and all possible – and unimaginable – methods like building internment camps and locking up millions of innocent people. Uyghur intellectuals are a leading force in the Uyghur society that keep Uyghur language alive, as well as fostering all aspects of Uyghur ethnic identity, culture and history. The Chinese government is targeting

Uyghur intellectuals and elites in order to re-engineer the mass of Uyghur population to suit a Han Chinese nationalistic vision and nationalist interests. China is right now in the middle of a process designed to meet the goal of permanent occupation of the Uyghur homeland, and fully prevent any kind Uyghur dissident or ethnic and cultural rights movement that may bring one day in the future a push for Uyghur independence.”

Rahima Mahmut: “The Chinese government has been carrying out assimilation policy for decades, as the totalitarian regime cannot tolerate the existence of Uyghurs who have a very different language, culture, and religion. The targeting of Uyghur scholars, artists and intellectuals has a long history and was focused on those who held strong differences of opinion. However, since 2016, the attacks on the Uyghur intellectuals has reached to an unpresented level with the implementing of the policy to eradicate the Uyghur language, culture and religion, as the intellectuals are considered to be the biggest obstacle for the Chinese government in achieving its cultural cleansing policy.

So, in order to achieve their objective, the intellectuals must be intimidated and brainwashed, and that is why they are disappearing, detained in so called re-education camps or serving long term prison sentences. Uyghur intellectuals are the heart and soul, also the backbone, of Uyghur dignity and pride. Destroying the intellectuals is one of the crucial steps in destroying the entire Uyghur cultural identity and ethnic pride. All the ethnic cleansing and cultural genocide throughout history has followed a similar pattern. What is happening to the Uyghur people now has strong similarities to what was implemented by the Nazi regime.”

Elise Anderson: “The Party is targeting cultural elites because it wants to send the message that it allows no space for any genuine expression of what it means to be Uyghur, which has always been an index of distinction from the mainstream in China. The fame and social visibility elites makes their disappearances more visible than those of the average person, amplifying the Party’s message more loudly and clearly to a broad public.”

What are the long-term implications of targeting Uyghur intellectuals?

Darren Byler: “This process of eliminating figures of influence within a Native (Uy: yerliq) society serves multiple purposes. First, in the past these figures served as models for younger generations of Uyghurs. Their criminalization sends the message throughout Uyghur society that the space for permitted difference, for Uyghur-ness, has now been drastically reduced. It makes it clear that any self-determined celebration of Uyghur values is no longer permitted. In addition, a lack of native Uyghur leaders will produce feelings of lack and self-loathing among the next generations of Uyghurs because Uyghur-ness will likely be seen as a source of stigma and ‘backwardness.’

Second, this targeting also makes clear that any understanding of Uyghur history and aesthetics outside of a Han-centric narrative is no longer permitted. Uyghurs are now on the verge of becoming a people without history or self-determined knowledge. The elimination of the Native is always ultimately the goal of colonial projects. The targeting of formerly state-approved Native intellectuals drives home the point that this is indeed a violent colonial project that is attempting to eliminate the Uyghur elements of Uyghur society and replace them with Han cultural elements and Chinese patriotism. This is a producing a continuum of violence that extends from the symbolic attacks on Uyghur knowledge to the material violence of prison camps. By eliminating Uyghur leaders, the Chinese state hopes to decimate Uyghur social structure.”

Tahir Hamut: “Uyghurs are a weak ethnic group in China. After 1949, Uyghurs have been marginalized by the Chinese Communist Party. In this process, Uyghurs have been enduring the double oppression of the Chinese Communist Party and the Han culture. But Uyghurs have been trying to improve their destiny. Especially since the 1980s, a large number of Uighur elites have emerged in various fields. It is very difficult in East Turkistan under Chinese control to become an intellectual. Ordinary Uighurs hold great hopes for these elites. Therefore, the attack on these elites will destroy the hope of Uyghur society and plunge Uyghurs into despair. Perhaps the Communist Party of China would like to see this result.”

Aziz Isa: “The long-term implication is unthinkable and very depressing because China is now attacking Uyghur intellectuals and destroying Uyghur ethnic and culture heritage. Even if we think China will stop the policies of ethnic and cultural cleansing of the Uyghurs, it will take several decades for the Uyghurs to recover. The loss will be so great and it’s unbearable to think it has been continuing for more than two years already, and so many countries are staying silent rather than calling on China to stop committing crimes against Uyghur people.”

Rahima Mahmut: “By destroying the scholars, artists, and intellectuals there will be a void, as there will be no one to represent the thoughts and direction that future generations require to build for the future, using their deep historical and cultural knowledge. Eradicating the intellectuals in my opinion could possibly lead to two extreme opposing situations. One is total submissive obedience, where Uyghurs will submit themselves to accept whatever they are told or ordered to do. They will gradually lose their cultural identity. The second possibility is that those who disagree with the eradication policy in the long term will turn to extremism. The outcome is that the crackdown on intellectuals and academics will cause irreversible consequences, which is a huge loss for the Uyghur people and the world as a whole. At the same time this outcome will not be beneficial to the Chinese authorities within the country or on the world stage.”

Elise Anderson: “The long-term implications are grim. Uyghurs are losing culture-bearers who have written the books that helped them make sense of history and identity, who have made the art that helps them to understand themselves. No, these traditions will not be completely lost overnight, and there is hope for revival and healing if the horrible situation ever improves, but the road to that revival looks to be a long and traumatic one.”

VI. Recommendations

To the Government of China

- The government of China must immediately release all those detained and sentenced for their ethnicity, religion, or peaceful exercise of their fundamental human rights.

- The government of China must ensure that Uyghur children forcibly taken away to state orphanages are restored to their families and provide restitution to all victims.

To International Actors

- The international community must act urgently, before it is too late, to condemn the Chinese government’s unconscionable persecution of Uyghur intellectuals.

- Universities should press the Chinese government for proof of life, and the immediate release, of detained Uyghur scholars and students, with a special focus on individuals who have obtained degrees, conducted research, or given lectures at their institutions.

- Governments should press the Chinese government for proof of life, and the immediate release, of detained Uyghur scholars, students, journalists and artists.

- Universities should suspend cooperation with the Ministry of Education and the Hanban (Confucius Institute Headquarters) until the government releases all persecuted intellectuals, artists, and journalists; enables them to be reunited with their families, including children who have been forcibly taken to state orphanages; makes restitution; and brings their persecutors to justice.

- International scholars and students should not participate in academic exchanges or conferences involving higher-education officials from China, until the camps are closed, and restitution is made.

- Governments, universities, and private foundations should provide scholarships and fellowships for Uyghur students and scholars abroad who cannot return home due to the grave risk of detention, torture and death in custody. Colleges should waive tuition for enrolled Uyghur students who have no means of support due to losing contact with their families.

- Scholars should join the Xinjiang Initiative (xinjianginitiative.org) to raise the issue of Uyghur human rights at public events, and sign the Statement by Concerned Scholars on China’s Mass Detention of Turkic Minorities (https://concernedscholars.home.blog/).

VII. Acknowledgements

The Uyghur Human Rights Project would like to thank the brave individuals who, despite the threat of Chinese government reprisals, have come forward to speak about their relatives suffering in the Uyghur Region. Human rights documentation rests fundamentally on this kind of courage. UHRP is fortunate to work with such people. UHRP also thanks the experts who contributed their time to offer comments on the persecution of Uyghur scholars, journalists, and artists. Their work ensures the public has access to nuanced analysis of the current crisis in the Uyghur region. Finally, UHRP thanks Abduweli Ayup, who has kept a record of impacted Uyghur intellectuals. His service to his people deserves wide recognition and appreciation.

Many people have worked hard to make sure this report is accurate and objective. The author would like to thank UHRP’s staff for invaluable guidance and their human rights expertise. UHRP would like to thank the individuals who support our work with their donations and extends special appreciation to the National Endowment for Democracy, whose unwavering support for freedom, democracy, and human rights ensures that Uyghurs will always have a voice.

VIII. Methodology

The information in this report is a synthesis of primary and secondary sources. Primary source data was gathered in verbal and written interviews conducted in Uyghur and English in February and March 2019. UHRP spoke to Uyghurs whose relatives have been interned, imprisoned, and disappeared in China. Interviews with analysts were conducted in writing. Interviewees were selected through existing networks. UHRP worked with Uyghur scholar Abduweli Ayup to compile the list of impacted intellectuals, relying on verification through a variety of confirmation methods, including information and analysis provided by the Uyghur exile community, relatives, and the overseas media. The long reach of Chinese government repression extends beyond the region to the Uyghur diaspora and others who speak critically even overseas. For this reason, UHRP offered complete anonymity to interviewees who requested it. One interviewee asked for anonymity. To protect the interviewee, UHRP changed identifying details for this one testimony.

Detained and Disappeared: Intellectuals Under Assault in the Uyghur Homeland supplements and updates two previous UHRP Reports:

The Persecution of the Intellectuals in the Uyghur Region Continues | 338 known to have been taken away | Jan 28, 2019.11uhrp.org. (2019). The Persecution of the Intellectuals in the Uyghur Region Continues. [online] Uyghur Human Rights Project. [Available at: https://uhrp.org/press-release/persecution-intellectuals-uyghur-region-continues.html [Accessed 12 Mar. 2019].

The Persecution of the Intellectuals in the Uyghur Region | 231 known to have been taken away | Oct 22, 2018.12uhrp.org. (2019). The Persecution of the Intellectuals in the Uyghur Region: Disappeared Forever?. [online] Uyghur Human Rights Project. Available at: https://uhrp.org/press-release/persecution-intellectuals-uyghur-region-disappeared-forever.html [Accessed 12 Mar. 2019].

IX. Appendix

For the full list of interned, disappeared, and imprisoned Uyghur intellectuals, please visit: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1kjNKUYhGy9CoN7aMjtYdggipe2I4SivTlZvSm6ufRlw/edit?us p=sharing.

FEATURED VIDEO

Atrocities Against Women in East Turkistan: Uyghur Women and Religious Persecution

Watch UHRP's event marking International Women’s Day with a discussion highlighting ongoing atrocities against Uyghur and other Turkic women in East Turkistan.