A Uyghur Human Rights Project report by Nicole Morgret. Read our press statement on the report here, and download the full report here.

I. Executive Summary

This report seeks to document the various methods the Chinese government employs to monitor and harass Uyghurs overseas. Uyghurs are subjected to coercion from the Chinese government even after leaving China. The targets of this coercion are not limited to the politically active, but also the Uyghur diaspora more broadly, creating a climate of fear even in liberal democracies in the West.

Although one of the primary goals of the Chinese government’s harassment of Uyghurs abroad is to discourage and disrupt political activism among them, it also effects the community more broadly as the Chinese security services seek to recruit members of the community to carry out espionage against others, replicating the system of control that exists in their homeland. Threatening retaliation against family members who remain within the borders of China is one of their primary tools. Not only are members of the Uyghur community overseas faced with the possibility of never being able to see or speak to their family members again, but they are also running the risk of their family being targeted for their non-cooperation. This targeting includes everything from their family members being prevented from leaving China by being denied passports, to putting their jobs and educations at risk, to being subjected to imprisonment.

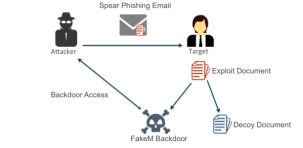

Technological development has opened a new front in the Chinese authorities’ struggle against Uyghur dissidents. Email and the internet have created new opportunities to monitor the activities of Uyghur activists, who find themselves frequently targeted by attempts to gain access to their communications, many of which contain sensitive information. This makes communicating with Uyghurs still in China very risky, as phone calls can be monitored more easily than in the past.

China has long targeted dissidents abroad, seeking to control the narrative of Chinese politics within Chinese communities overseas though tools such as the education departments of their embassies and consulates, for example using them to disrupt events held by activists on college campuses and elsewhere. They have also tried to influence and put pressure on foreign governments to label Uyghurs as “terrorists” and to prevent their free movement, even after they have become citizens of other countries.

Uyghurs find themselves subjected to monitoring and harassment by the Chinese security services even after they leave China. Countries China has built closer security relationships with, such as Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, have used their own security forces to attempt to shut down political activities among Uyghurs in their nations, or even detain and deport Uyghurs living legally in their territory.

These tactics undermine Uyghurs’ ability to enjoy their legal rights even in Western nations, as well as countries in Central Asia which have closer security cooperation with China. Fear that their families back home could suffer for their political opinions or activities creates an atmosphere of insecurity that can make Uyghurs living abroad reluctant to speak up about their experiences or the general situation in East Turkestan. This has a negative impact on the outside world’s knowledge of the region, undermining efforts to improve the human rights situation there.

II. Background

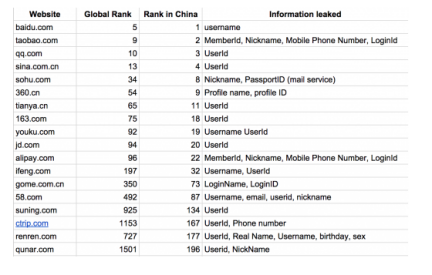

The Chinese government expends a great deal of effort on monitoring the activities of its citizens within its borders. The measures it takes to monitor and control the internet are well documented, leaving it at last place among countries surveyed on Freedom House’s annual Freedom on the Net report.1Freedom House (2016) “Freedom on the Net 2016: China” Retrieved from https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2016/china Also well known is the government’s harassment and monitoring of dissidents within its borders;2Wang, Maya (2016, August 15) “China’s Human Rights Crackdown Punishes Families, Too” Human Rights Watch Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/08/15/chinas-human-rights-crackdownpunishes-families-too the authorities’ efforts at control are strongest in the majority-minority regions of East Turkestan and Tibet.3Coca, Nithin (2016, August 20) “The slow creep and chilling effect of Chinese censorship” Daily Dot Retrieved from https://www.dailydot.com/layer8/china-tibet-xinjiang-censorship/ However, the Chinese government’s control and monitoring of the activities of their citizens or former citizens do not stop at the Chinese border. The large Uyghur population in Central Asia concerns Beijing,4Lal, Rollie (2006) “Central Asia and its Asian Neighbors: Security and Commerce at the Crossroads” RAND Corporation Retrieved from http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monographs/2006/RAND_MG440.pdf and as the numbers of Uyghurs living abroad in the West grows, so do the Chinese government’s efforts to keep tabs on them and to deter them from activities that they perceive as possibly threatening to their rule over East Turkestan.

Although the Chinese authorities take a particular interest in them, Uyghurs are not the only group of Chinese nationals and former nationals who are subjected to surveillance and harassment by the Chinese government overseas. The government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has maintained an interest in influencing and observing the members of overseas Chinese communities since it took power. This interest has always been closely linked to fears of separatism and opposition to the government; the Chinese intelligence services are “relatively less risk averse” when engaging Chinese disapora communities with the aim of combating Taiwanese influence and the perceived threat of the “Three Evil Forces,” of separatism, terrorism and religious extremism, says Nigel Inkster, former Director for Operations and Intelligence of MI6.5Inkster, Nigel (2015) “The Chinese Intelligence Agencies: Evolution and Empowerment in Cyberspace” in China and Cybersecurity: Espionage, Strategy, and Politics in the Digital Domain, ed. Jon R. Lindsay, Tai Ming Cheung, and Derek S Reveron, Oxford University Press

In the early decades of the PRC the objective of its influence operations overseas was winning the battle for legitimacy among overseas Chinese and opposing Taiwan’s de facto separation from the mainland. This work fell to the United Front Work Department and the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office, under the authority of the State Council, tasked with carrying out qiaowu, or “overseas Chinese affairs work.” After the PRC replaced the Republic of China in the United Nations, undermining advocacy of Taiwanese independence became the primary goal of Taiwan-related qiaowu activity.

During the decades under Mao, China was largely inwardly focused, but after reform and opening overseas Chinese communities in the West expanded rapidly and diversified. Chinese nationals began both sojourning for short periods as businessmen or students and emigrating in large numbers.6Xiang, Biao, (2016, February) “Emigration Trends and Policies in China: Movement of the Wealthy and Highly Skilled” Migration Policy Institute Retrieved from file:///Users/rrife/Downloads/TCM_EmigrationChina-FINAL.pdf However, the catalyst for the expansion of the authorities’ efforts to influence and monitor them was the Tiananmen Square Massacre and the large number of dissident exiles it produced. The Overseas Chinese Affairs Office is an overt means of doing this, and according to scholar James To, the CCP has “successfully unified cooperative groups for its own interests, while seeking to prevent hostile ones from eroding its grip on power.”7To, James (2012) “Beijing’s Policies for Managing Han and Ethnic-Minority Chinese Communities Abroad” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 41, 4, Retrieved from https://d-nb.info/103224626X/34

The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region has its own Overseas Chinese Affairs Office focused on Central Asia, including its Uyghur population. Elena Barabantseva describes its official language as “emphasizing [their] negative relation to China,” connecting them to potential separatist forces.8Barabantseva, Elena (2014) “Translating ‘Unity in Diversity’: The predicament of ethnicity in China’s diaspora politics” in European-East Asian Borders in Transition Routledge “Unlike its practices toward Han overseas Chinese, which stress mutual ‘blood ties,’ culture, values, interests and patriotism,” the Chinese government’s engagement with overseas Uyghurs is based “on the assumption that they might otherwise pose a threat to Chinese security,” especially in the wake of Central Asian nations gaining independence from the Soviet Union.9Ibid. It was also during the post 1989 period that there began to be significant numbers of Uyghurs living in the West, beyond Central Asia and Turkey where overseas Uyghur communities were previously concentrated. As one of the potentially hostile groups mentioned above, these communities became objects of suspicion to the Chinese government.

In the words of the German Ministry of the Interior:

A substantial part of the spying activities in Germany is directed against efforts that – in the eyes of the Chinese government – jeopardise the Communist Party’s monopoly on power and China’s national unity. This includes the ethnic minorities of the Uighurs and Tibetans, the Falun Gong movement, the democracy movement and proponents of sovereignty for Taiwan. These groups and organisations are defamed by the Chinese authorities as the ‘Five Poisons.’10Federal Ministry of the Interior (2016, June) “2015 Annual Report on the Protection of the Constitution: Facts and Trends” https://www.verfassungsschutz.de/en/public-relations/publications/annualreports/annual-report-2015-summary

Official Chinese rhetoric about overseas Uyghurs is full of accusations of conspiracies on which any tensions and issues in East Turkestan can be blamed; the activities of Uyghur reporters and human rights advocates are characterized as “terrorist” without credible evidence to support such claims, according to the US State Department.11United States Department of State Bureau of Counterterrorism and Countering Violent Extremism (2015, June) “Country Reports on Terrorism 2014” Retrieved from https://www.state.gov/j/ct/rls/crt/2014/239405.htm Their goal in infiltrating the Uyghur community overseas is not simply to gather information about their activities, but to intimidate them into silence. Gentle methods of influence like those of the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office are of no use against groups resistant to the Chinese government. In these cases, says James To, the “CCP authorities resort to direct interference by harassing, blacklisting or attacking hostile elements. Such work goes beyond the scope of the qiaowu administration, and is implemented through other government agencies such as the MFA and the Ministry of State Security (MSS).”12Ibid.

Because espionage work is inherently obscure it is not always clear which department is conducting the work of monitoring the Uyghur community overseas. The MSS is China’s principle civilian intelligence agency, carrying out intelligence gathering both overseas and domestically, especially concerning “security cases and issues ‘linked to foreign factors’ or ‘foreign organizations,’ including those operating inside China, or those trying to enter China.”13Bellaqua, James and Tanner, Murray Scott (2016, June) “China’s Response to Terrorism” CNA Retrieved from https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/Chinas%20Response%20to%20Terrorism_CNA061616. pdf However, it is likely not the only ministry responsible for monitoring of Uyghurs abroad. Although the Ministry of Public Security’s (MPS) area of responsibly is primarily domestic policing, through its Domestic Security Protection departments it plays a “major role in policing political dissent, ethnic separatism, unapproved religious activities, and espionage… domestic security departments are also responsible for much of the police’s secret investigation work, as well as some of the public security system’s overseas investigation work (called ‘investigation and research outside the border,’ or jingwai diaoyan (境外调研).”14Ibid. This accords with the experience of Uyghurs who have been pressured to report on other members of the overseas Uyghur community who describe being contacted over the phone by individuals identifying themselves as MPS agents or being required to meet with MPS agents when returning to visit East Turkestan.

This report will focus on cases of harassment and monitoring of Uyghur communities in the West, including North America, Europe, and Australia as well as Turkey, Central Asia and Pakistan’s small Uyghur community. It will examine the main tactics used by the Chinese authorities to harass and intimidate overseas Uyghur communities, including widespread efforts to recruit members of the community as informants to report on other members, using the threat of retaliation against their family members still in East Turkestan, attempts to intimidate reporters and activists, and spying on and using cyberattacks to disrupt their online communications. This report will utilize interviews with individuals who have experienced this kind of harassment, as well as cases that are already known to the public via media reports.

III. Monitoring of Overseas Uyghurs and Recruitment for Espionage

Considering the ethnic separatism activities outside of the border, carry out all necessary dialogue and struggle. Strengthen the investigation and study outside of the border. Collect the information on related development directions of events, and be especially vigilant against and prevent, by all means, the outside separatist forces from making the socalled ‘Eastern Turkistan’ problem international. Divide the outside separatist forces, win over most of them and alienate the remaining small number and fight against them. Establish home bases in the regions or cities with high Chinese and overseas Chinese populations. Develop several types of propaganda. Make broad and deep friends and limit the separatist activities to the highest degree.15Chinese Communist Party Document No. 7 (1996) “Record of the Meeting of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the Chinese Communist Party concerning the maintenance of Stability in Xinjiang” Retrieved from http://caccp.freedomsherald.org/conf/doc7.html

So reads a leaked 1996 document from the Central Committee on a meeting chaired by Jiang Zemin regarding “the task of defending the stability of Xinjiang.” Though it is referring largely to the Uyghur communities in Central Asia, it does illustrate that the CCP’s tactic of infiltrating overseas Uyghur groups is a longstanding one, and is part of its overall strategy to maintain stability in the region.

This strategy has long been used by the Chinese authorities against not only the Uyghur diaspora but also against the Chinese dissident community more broadly. The government of the United States openly acknowledges “Chinese operatives and consular officials are actively engaged in the surveillance and harassment of dissidents on U.S. soil.”16U. S. -China Economic and Security Review Commission (2009, November 1) “Report to Congress of the U. S. -China Economic and Security Review Commission 2009” Retrieved from https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/annual_reports/2009-Report-to-Congress.pdf The defection in 1990 of Xu Lin, a Chinese diplomat in the Washington, D.C. embassy’s education section, revealed some of the targets and techniques employed by the Chinese authorities in the immediate aftermath of the Tiananmen Square massacre. The MSS and MPS used the embassy’s education departments to monitor Chinese nationals abroad for democratic sympathies, and recruit others to monitor their peers.17Eftimiades, Nicholas (1994) “Chinese Intelligence Operations” Naval Institute Press The authorities pressured Chinese nationals abroad not to express any pro-democratic sympathies by threatening their job prospects and the safety of their relatives back home in China, as well as their access to passports.

Given the opacity of intelligence operations in general, and China’s system in particular, it can be difficult to discern where a Chinese embassy’s mission to influence Chinese groups abroad ends and targeted recruitment for espionage begins. Peter Mattis, an expert on the Chinese intelligence services, states that “it is possible, if not probable, that Chinese intelligence recruited agents in ethnic Chinese overseas communities, Chinese ethnic minorities, and Taiwanese, but U.S. and other local counterintelligence services did not focus on such activities. In democracies, such activities may not even necessarily break the law.”18Mattis, P. (2016, June 9) “Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission: Chinese Human Intelligence Operations against the United States” Retrieved from https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Peter%20Mattis_Written%20Testimony060916.pdf Nevertheless, there have been a several cases in Europe involving individuals being recruited to spy on the Uyghur community that have resulted in prosecutions, as well as reports of attempts being made to recruit them that have appeared in the media in North America.19Vanderklippe, Nathan (2017, October 29) “How China is targeting its Uyghur ethnic minority abroad” Globe and Mail Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/uyghurs-around-the-worldfeel-new-pressure-as-china-increases-its-focus-on-thoseabroad/article36759591/

The Uyghur community within China is well acquainted with the authorities encouraging them to report on one another in order to monitor the political and religious attitudes of its members. This pressure continues overseas, as the Chinese authorities can use threats against the family members remaining within Chinese borders to coerce Uyghurs overseas to report on the activities of the diaspora.

The authorities’ attempts to recruit informers do not always involve direct contact. One example of this is the experience of Parhat Yasin, a Uyghur who has lived in the in the United States since the late nineties. In 2004, he received several phone calls from Public Security Bureau (PSB) officers in his hometown of Ghulja. One caller identified himself as the head of Ghulja’s PSB, and others later called and, using the Uyghur language, told him that they would give his wife and children passports in exchange for him passing information to the PSB about the identities and activities of other Uyghurs he knew.20Radio Free Asia (2006, March 5) “US Based Uyghur Says Chinese Officials Pressured Him to Spy” Retrieved from http://www.rfa.org/english/news/politics/uyghur_spies-20060105.html

Most Chinese attempts to recruit informers do not take place entirely on foreign soil, but involve a direct link to China whether over the phone, or as in the case of Canadian citizen Erkin Kurban, take place inside China. Kurban is unusual in his willingness to speak to Canadian authorities and the media about his experience, as most Uyghurs fear reprisals to their family members within China. In an interview with UHRP, Kurban said that his experience began with an attempt to get a visa in 2013 to return to East Turkestan to visit his elderly mother.21Erkin Kurban, Interview with Uyghur Human Rights Project 2017 He had been denied a Chinese visa in previous attempts, but on this occasion MPS officials visited his brother in Urumqi and told him that Kurban would be granted a visa if he agreed to cooperate. Upon hearing this message from his brother Kurban reapplied and was given a visa.

Before he left, he told Canadian authorities of his plans, fearing the possibility that he might be detained. Three days after his arrival in Urumchi he was interrogated for 10 hours at the MPS office. Four Chinese officials who spoke fluent Uyghur questioned him. Despite having agreed to help them, they were threatening, saying that his Canadian citizenship would not protect him. He avoided giving any accurate or useful information to them, but said that they already seemed very well informed about the Uyghur community in Canada. He was questioned several more times before he left. When he returned he immediately shared his story with the press and the Canadian authorities. He said that this tactic is used to intimidate the Uyghur community, and that it has been quite successful. Many Uyghurs are suspicious of each other, especially those who are able to travel easily and frequently back and forth between Canada and China, Kurban told UHRP.22Ibid.

Kayum Masimov, a former president of the Uyghur Canadian Society, told UHRP that this type of pressure on the Uyghur community has worsened over the past decade, and the level of fear in the Uyghur community in Canada has increased.23Kayum Masimov Interview with Uyghur Human Rights Project 2017 He said that the cases he is aware of are like that of Erkin Kurban- Uyghurs returning home to visit their families are called into the local police stations to “have tea” and asked about their activities and acquaintances in Canada. The security officials often already knew a considerable amount during these interviews, including where Uyghurs in Canada lived and where they were employed. There have not been any public cases in Canada of Uyghurs drawing the attention of the authorities for espionage activities, although an individual was ordered deported from the country in 2008 for espionage against Inner Mongolian activists, albeit conducted in Mongolia and the United States.24Bell, Stewert (2010, February 25) “Former Chinese spy seeks asylum in Toronto Church” National Post Retrieved from http://www.phayul.com/news/tools/print.aspx?id=26729&t=0

Europe has had a number of publicly reported cases of Uyghurs as a target for Chinese espionage. In 2011, the General Intelligence and Security Service of the Netherlands reported that the Chinese authorities take an interest in ethnic minorities overseas and that “Uyghurs, in particular, are tightly monitored and even put under pressure to collect information about other members of their community. Chinese agents have attempted to infiltrate Uyghur organisations in the Netherlands, and China has very detailed knowledge of their internal affairs. The purpose of these activities is to maintain a grip on the community, preventing it from organizing effectively.”25Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations General Intelligence and Security Service (2012, June) “Annual Report 2011” Retrieved from https://english.aivd.nl/publications/annualreport/2012/06/28/annual-report-2011

In the view of many Uyghur activists in Europe this strategy is quite widespread and effective in both allowing the Chinese government to maintain knowledge of the Uyghur community and to dissuading many Uyghurs from participating in any political activities and even simply maintaining contact with others in the Uyghur diaspora community. In an interview with UHRP, Enver Tohti, an ethnic Uyghur activist who resides in London, said that several Uyghurs have openly told him that they are reporting to the Chinese government. They told him they felt it was necessary to do so, but wanted to warn him not to say anything to them that he would not wish the Chinese government to know.26Enver Tohti Interview with Uyghur Human Rights Project 2017 He was told that the authorities use the family members of the people they target for recruitment. Those who have agreed to cooperate meet their family members, along with a Chinese agent, in third countries such as Thailand and Malaysia.27Ibid.

A 2009 case involving a Uyghur in Sweden demonstrated the Chinese government is becoming more confident in its intelligence activities abroad. Peter Mattis notes that before this case was uncovered “no exposed Chinese espionage case occurred without operational activity inside China —that is, no operation occurred without a physical connection to China.”28Mattis, P. (2012, September) “The Analytic Challenge of Understanding Chinese Intelligence Services Studies” in Intelligence Vol. 56 No 3 Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-ofintelligence/csi-publications/csi-studies/studies/vol.-56-no.-3/pdfs/MattisUnderstanding%20Chinese%20Intel.pdf Naturalized Swedish citizen Barbur Mehsut was arrested on charges relating to “unlawful acquisition and distribution of information relating to individuals for the benefit of a foreign power,” for which he received monetary compensation as well as a visa for his daughter and a job for his wife; he was eventually sentenced to sixteen months in jail.29Goldstein, Ritt (2009, July 14) “Is China Spying on Uighurs Abroad?” Christian Science Monitor Retrieved from http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Asia-Pacific/2009/0714/p06s12-woap.html Mehsut had attended meetings of the World Uyghur Congress, including ones held outside of Sweden such as the third General Assembly of the World Uyghur Congress in May 2009 in Washington D.C. The WUC did not suspect him as a possible spy. He passed information on the activities, health, and finances of Uyghur activists in Sweden, Norway, Germany and the U.S. to Zhou Lulu, a press officer at the Chinese Embassy in Stockholm and People’s Daily Sweden correspondent Lei Da.30Swedish Security Service (2010, September)“The Swedish Security Service 2009” Retrieved from http://www.sakerhetspolisen.se/download/18.635d23c2141933256ea1c76/1381154798357/swedishsecurity service2009.pdf The two were expelled from Sweden after the case came to light; China expelled a Swedish diplomat in retaliation. Sweden’s Security Service (Säpo) built their case though wiretaps and surveillance of their meetings.

A particularly high priority for the Chinese agent was the case of Adil Hakim, one of the Uyghurs formerly held at Guantanamo who was in the process of applying for asylum in Sweden at the time. In her capacity as press officer, Zhou Lulu had argued for Sweden to hand Hakim over to China.31Goldstein, Ritt (2009, April 4) “Freed from Guantanamo, a Uighur Clings to Asylum Dreams in Sweden” Christian Science Monitor Retrieved from http://www.csmonitor.com/World/2009/0424/p06s04-wogn.html China was concerned that if his case was approved a precedent would be set for more Uyghurs to settle in Sweden as asylum seekers, Mehsut told police. Despite the fact that the case was public, China was anxious to get information directly from the source. Mehsut frequently called him asking for the details of his ongoing case, Hakim told a Swedish radio program.32Konflikt (2010, March 28) “I Spy…” Svergies Radio Retrieved from http://sverigesradio.se/sida/artikel.aspx?programid=1300&artikel=3587439 Mehsut was even among those who met him at the airport upon his arrival in Sweden from Albania; he advised Hakim not to speak to the press and not to answer any of their questions about China. Many details of the case remain classified for the sake of Swedish-Chinese relations.

The Swedish authorities take what they call ‘refugee espionage’ seriously; the Security Service’s website describes it as unlawful intelligence activity and political persecution, warning that it may “undermine the democratic process, and lead to a situation where people who have sought asylum in our country may no longer feel able to enjoy their constitutional rights and freedoms.”33Swedish Security Service “Counter-espionage: Refugee Espionage” http://www.sakerhetspolisen.se/en/swedish-security-service/counter-espionage/refugee-espionage.html The case of a suspect arrested in February 2017 on suspicions of spying on the Tibetan community suggests that the Chinese security services continue to use these tactics even in countries where they have been caught before.34The Local (2017, March 1) “Man suspected of spying on Tibetans in Sweden on behalf of China” Retrieved from https://www.thelocal.se/20170301/man-suspected-of-spying-on-tibetans-in-sweden-onbehalf-of-china

Dilshat Raxit, Sweden-based spokesman for the World Uyghur Congress, says that the problem continues to be widespread in Sweden, with four or five Uyghurs in the past three years having told him that they had been approached by officials from the Chinese embassy and been pressured to spy.35Dilshat Raxit Interview with Uyghur Human Rights Project 2017 He believes their methods have become subtler and more effective since the Mehsut case was revealed. They usually target students or those in Sweden on work visas. They seek information on the activities of the Uyghur diaspora in Sweden, and tell them that by cooperating they will receive the embassy’s assistance as they study or work there; if they refuse, they have their passports confiscated because of “technical problems” and are forced to return to China. Two people he knows of told the Swedish police about the Chinese embassy approaching them and sought asylum, although they were reluctant to do so. Because of this many Uyghurs in Sweden for work or study avoid having any contact with those in the diaspora, according to Raxit. Surprisingly it is not only Uyghurs who are subjected to this kind of pressure; Raxit said he was aware of a case of an ethnic Han from Urumqi staying in Sweden on a work visa who was brought into the embassy and pressured to spy on the Uyghur community.36Ibid.

Another Uyghur resident in Sweden told UHRP that his parents had been called into a local police station and shown detailed knowledge of his activities abroad, including travels to different countries in Europe.37Interviewee A, Interview with Uyghur Human Rights Project, 2017 His father was asked to convince his son to stop his activities, and was told to go to Sweden to do so in person. His application for a visa was turned down by the Swedish embassy in Beijing, who had been informed of the situation. The Uyghur Swedish citizen was also aware of others who had been called into police stations when visiting home and shown surveillance photos of themselves before being asked to report on the health, income, and activities of Uyghur political activists. Chinese visas and other incentives are provided to those who agree to cooperate. The interviewee said that in his opinion the Chinese embassy gives and denies visas to Uyghur foreign nationals randomly: “In this way, you can divide the Uyghur society and create suspicions against each other as he may work for China’s behalf.”38Ibid.

One Uyghur asylum seeker in Sweden in an interview with UHRP in 2011 described his experience of the authorities attempting to recruit him as an informer.39UHRP (2011, September) “They Can’t Send Me Back: Uyghur Asylum Seekers in Europe” Retrieved from http://docs.uyghuramerican.org/UHRP-report-Uyghur-asylum-seekers-in-Europe.pdf He was not granted a passport until he agreed with the secret police to inform on the Swedish Uyghur community, suggesting that it remains an important target for the authorities. After not reporting to the Chinese embassy in Stockholm, his family in China received a visit from the local authorities enquiring after his whereabouts, and he continued to receive weekly emails asking him for information on the Swedish Uyghur community. Another asylum seeker in Sweden told the Swedish media that her family had been visited by the authorities in East Turkestan who told them to try to convince her to come back, and that she would be charged with separatism and revealing state secrets, but that her punishment would be milder if she agreed to cooperate and report on other Uyghurs in Sweden.40Konflikt (2012, July 28) “Kina kontrollerar uiguriska flyktingar i Sverige” Sveriges Radio Retrieved from http://sverigesradio.se/sida/artikel.aspx?programid=83&artikel=5170317

The same year as the Swedish case was made public, Germany uncovered a case of a Uyghur passing information about the diaspora to Chinese consulate staff in Munich. As the location of the headquarters of the World Uyghur Congress, as well as home to a large population of Uyghurs, it is a prime location to conduct espionage. The initial investigation led to the arrest of four suspects, all Chinese nationals, their identities protected under German law.41Stark, Holger (2009, November 24) “Germany Suspects China of Spying on Uighur Expatriates” Spiegel Online Retrieved From http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/police-raid-in-munich-germanysuspects-china-of-spying-on-uighur-expatriates-a-663090.html One of the accused was not a Uighur, although he had previously worked as a teacher in East Turkestan. The officer of the Chinese embassy who handled him was initially the head of the cultural department, later promoted to General Consul.42tz Online (2011, September 23)“Bewährungsstrafe für chinesischen Spion” Retrieved from https://www.tz.de/muenchen/stadt/bewaehrungsstrafe-chinesischen-spion-1417652.html Three were charged in 2011 and given suspended sentences.43Mooney, Paul and Lague, David (2015, December 30) “Holding the fate of families in its hands, China controls refugees abroad” Reuters Retrieved from http://www.reuters.com/investigates/specialreport/china-uighur/

Germany’s Office for the Protection of the Constitution (BfV) was aware of Chinese efforts to monitor Uyghur activities on German soil before this incident. Both the BfV and its regional Bavarian office have published letters confirming Chinese authorities’ interest in monitoring Uyghurs on German soil, including those not involved in political activism since the 1990s.44Sichor, Yitzak (2013, March 1) “Nuisance Value: Uyghur Activism in Germany and Beijing-Berlin Relations” Journal of Contemporary China, Vol. 22 Issue 82 ,http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10670564.2013.766383 In 2007, a Chinese diplomat in Munich, Ji Wumin, left the country before he could be expelled after being observed meeting with individuals passing information on the city’s Uyghur community numerous times. The Chinese government attempted to reassign him to the post several years later, but the German government blocked the move.45Stark, Holder (2009, November 24) “Germany Suspects China of Spying on Uighur Expatriates” Der Spiegel Retrieved from http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/police-raid-in-munich-germanysuspects-china-of-spying-on-uighur-expatriates-a-663090.html

The General Intelligence and Security Service (AIVD) of the Netherlands in its 2011 annual report stated that there was evidence that the Uyghur community in the Netherlands was being monitored by the Chinese government and targeted for recruitment for espionage, but the report did not detail how the AIVD came to that conclusion.46Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations General Intelligence and Security Service (2012, June) “Annual Report 2011” Retrieved from https://english.aivd.nl/publications/annualreport/2012/06/28/annual-report-2011 The next year two Uyghur translators were removed from their positions at the Immigration and Naturalization Service based on an AIVD report stating that they were reporting to the Chinese authorities. The cases they had been involved in were reinvestigated and a hold on deporting Uyghurs was implemented.47ANP (2013, April 26) “IND bekijkt Oeigoerse asielaanvragen nog eens” Retreived from http://www.bndestem.nl/overig/ind-bekijkt-oeigoerse-asielaanvragen-nog-eens~a385681e/ The interpreters filed a complaint with the Monitoring Committee of the Dutch Intelligence Service (CTIVD), which found that the AIVD’s report lacked sufficient evidence that state secrets were passed.48Rosman, Cyril (2013, August 22)” Oeigoerse tolken van IND niet vervolgd voor spionage” BN DeStem Retrieved from http://www.bndestem.nl/overig/oeigoerse-tolken-van-ind-niet-vervolgd-voorspionage~a0bd2c27/ The AIVD withdrew the report.49ANP (2013, September 10) AIVD fout met bericht over Oeigoerse tolken” Retrieved from http://www.nu.nl/binnenland/3571768/aivd-fout-met-bericht-oeigoerse-tolken.html

The AIVD has reported other instances of individuals passing information on dissidents to the Chinese embassy in the Netherlands. In 2008, a Beijing-born Chinese national working at the Xinhua bureau requested asylum but was ultimately denied due to the immigration officer finding his claim of fearing the Chinese authorities implausible.50Rechtbank den Haag, (December 2013) “18-12-2013 / AWB 09-38196” Retrieved from https://recht.nl/rechtspraak/uitspraak?ecli=ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2013:19432 The case featured an AIVD report stating that he had been giving information on the activities of the Falun Gong, Taiwanese, Tibetans and Uyghurs to the Chinese consul Sun Weidong. The individual claimed that only public information was given to the consul, and that his good relations with him were based only on the fact that they were from the same region. While perhaps not meeting the standard of formal espionage, the case fits into the pattern of Chinese state media journalists collecting information on dissidents.

The Australian government has also expressed concerns about the monitoring of Uyghurs on Australian soil. The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade stated in 2006: “It is likely that Chinese authorities seek to monitor Uighur groups in Australia and obtain information on their membership and supporters. In pursuing information, Chinese authorities would not necessarily exclude sources who do not have a political profile.”51Refugee Review Tribunal Australia (29 May 2006) RRT Research Response Number CHN31854. Retrieved from https://www.ecoi.net/file_upload/2107_1310371298_chn31854.pdf

Many asylum seekers in Australia cite their fear that there are informers who monitor the activities of Uyghurs abroad and report on attendance at Uyghur gatherings or political events, and fear their families will suffer repercussions. Some report that their families are repeatedly called in by the police in China and questioned about their activities abroad.52Australia Refugee Review Tribunal (2011, September 13) RRT Case No. 1105663 Retrieved from http://www.refworld.org/cases,AUS_RRT,4f1027022.html One Uyghur individual testified at another’s asylum hearing that upon returning China in “July 2008 she was questioned at the airport about a photo the authorities had showing the [asylum] applicant at the community gathering with Rebiya Kadeer. Asked at the hearing why they would show her the photo the witness said they were asking all Uyghurs because it was just before the Olympic Games and because she was a Uyghur returning from overseas.”53Australia Refugee Review Tribunal (2009, August 4) RRT Case No. 0903167 Retrieved from http://www.refworld.org/cases,AUS_RRT,4ad498502.html

In describing her experience to the Australian refugee tribunal, one Uyghur asylum seeker’s story shared many of features of the incidents that others have experienced.54Australia Refugee Review Tribunal (2012, April 20) RRT Case No. 1109939 Retrieved from http://www.refworld.org/cases,AUS_RRT,4fd854c32.html Before even leaving China in 2008 it was difficult for her to get a passport, and she had to pay a bribe for the each of the seven stamps that were required. After her arrival in Australia on a student visa, her parents were contacted by authorities in Urumchi and told by the authorities that they would be punished if she became involved in Uyghur political organizations. Her father was demoted at work after visiting her in Australia and being accused of “having contact and political discussions with Uighurs in Australia,” and her mother dismissed from her position after discussing the events in Guangdong that proceeded the July 5th unrest in Urumchi over the telephone with her daughter. After she left for Australia in 2008 her parents began to be regularly questioned about their daughter’s activities in Australia.55Ibid.

She returned to visit them in 2010 due to her worries about this treatment, and a “few days after she arrived in Urumchi, she said that the Chinese secret service came and took her away in a police car to a place where she was blindfolded and taken into a room where she was questioned about her activities in Australia. She says that she was asked about whether she was involved in any political activities in Australia, who she was in contact with, and whether she knew certain people. She was held and questioned for 2 days. The applicant maintained that she was a student and that she had no contact with Uyghur groups and did not know any of the people she was questioned about. After 2 days she was released and sent home.”56Ibid. Upon her return to Australia in January 2011 she hesitated to lodge her application for asylum due to her fears about possible further repercussions for her parents. Although her initial request for asylum was denied, the tribunal found in her favor in an appeal hearing due to her activities with Uyghur groups in Australia that put her at risk of persecution if she returned to China.57Ibid.

Not actively participating in political events or speaking out against Chinese government policies is not a guarantee that Uyghurs overseas will be left alone. Because the very act of seeking asylum has political implications, the Chinese government seeks to discourage Uyghurs from attempting to claim asylum overseas, often using the same tactics as those used to silence reporters and activists. In 2012, many Uyghur asylum seekers in Europe reported that the police in their hometowns were calling them. The police tried to persuade them by telling them their parents would have their passports revoked if their children did not return. The local authorities also threatened asylum seekers’ relatives in person, telling them they must persuade them to return from Europe or have their passports revoked, ensuring they would never be able to see their relatives again. One Uyghur interviewed by RFA wondered at the Chinese authorities’ ability to track asylum seekers- “What is strange is that this happened at almost exactly the same time. How did the police get this information? That is what baffles me.”58Radio Free Asia (2012, March 21) “Pressuring the Families of Uyghur Refugees” Retrieved from http://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/pressure-03212012185048.html

Cases of the Chinese government monitoring Uyghur communities abroad take place wherever there is a significant population of Uyghurs. Turkey has had a Uyghur population since before the 1950s, including prominent political exiles, allowing them to set up organizations and publications in the Uyghur language and resisting Chinese pressure to deport Uyghurs.59Sichor, Yitzak (2009) “Ethno-Diplomacy: the Uyghur Hitch in Sino-Turkish Relations” East-West Center Retrieved from http://www.eastwestcenter.org/fileadmin/stored/pdfs/ps053.pdf As in other countries with a significant Uyghur presence, the Chinese government makes efforts to infiltrate Uyghur organizations, creating suspicions that can lead to “paralysis and passivity.”60Ibid. The Chinese government has an interest in monitoring the Uyghur population of Turkey as a recent case illustrates. It was reported in the Turkish media that a Uyghur Chinese national with a Turkish residency permit was caught in May 2017 using her phone to take photos of people in Uyghur businesses in Istanbul.61Yeni Akit (2017, May 9) “O ajan istanbul’da yakayı ele verdi!” Retrieved from http://www.yeniakit.com.tr/haber/o-ajan-istanbulda-yakayi-ele-verdi-323392.html The employees of a Uyghur restaurant in Istanbul, all refugees, noticed her taking pictures of them and the patrons of the restaurant. Her phone had a number of pictures taken in Uyghur businesses in the city and she had been sending them to a Chinese phone number via WeChat. When taken to the police station she requested she be allowed to speak to the Chinese consulate, and was later released.62Ibid.

While not actively cooperating with the Chinese as Egypt has, there is still an increasing sense of insecurity in the Uyghur community in Turkey. In August 2016 the prominent Uyghur activist Abduqadir Yapchan was detained by Turkish authorities, a move instigated by the Chinese government according to other Uyghur activists.63Radio Free Asia (2016, October 10) “Exiled Leader Claims China is Behind Turkey’s Decision to Detain a Uyghur Activist” Retrieved from http://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/exiled-leader-claims-china10102016155133.html Yapchan was among the Uyghur activists placed on a list of terrorists released by China in 2003. Several days after he was detained Turkish President Erdogan met with Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Hangzhou and pledged to seek “’more substantive results in counter-terrorism cooperation.’”64Tham, Engen (2016, September 3) “China, Turkey pledge to deepen counter-terrorism cooperation” Reuters Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-g20-china-turkey/china-turkey-pledge-todeepen-counter-terrorism-cooperation-idUSKCN11905N Yapchan had previously been detained in Turkey in 2008, as then-Prime Minister Erdogan traveled to China.65World Uyghur Congress (2017, May) “2016 Human Rights Situation in East Turkestan” Retrieved from http://www.uyghurcongress.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/WUC-Human-Rights-in-East-Turkestan2017-1.pdf A judge initially ruled that there were no grounds for detaining him and he was released, only to be re-arrested the next day.66World Uyghur Congress (2016, December) “World Uyghur Congress December Newsletter” Retrieved from https://us4.campaignarchive.com/?u=29a2adbe90c2a0c8e045eb20e&id=f78c78fedc&e=%5BUNIQID%5D After being transferred to an immigration detention facility, the European Court of Human Rights released an interim decision that he should not be deported from Turkey until the case was settled. He refused to be transferred to Kazakhstan due to its close relations with China, and is currently seeking a third country with adequate protection of human rights.67Ibid. While in Beijing in August of 2017, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu stated that Turkey would not allow “any activities targeting or opposing China” and would “take measures to eliminate any media reports targeting China,” suggesting that the Turkish government may be beginning to take a more proChina stance.68Reuters (2017, August 3) “Turkey promises to eliminate anti-China media reports” Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-turkey/turkey-promises-to-eliminate-anti-china-media-reportsidUSKBN1AJ1BV

According to a Uyghur living in Turkey interviewed by UHRP, the Chinese embassy will not help Uyghurs with any documentation such as obtaining birth certificates or renewing passports without first getting them to cooperate with reporting on their relatives and social connections in Turkey, including their political attitudes and activities.69Interviewee B, Interview with Uyghur Human Rights Project 2017 The embassy makes no secret of this to the Uyghur diaspora in Turkey. One student had his background and social connections described to him by an embassy official, demonstrating that someone had already reported on him.

Several Uyghurs in Turkey received voice messages and WeChat messages asking about the political activities of Uyghurs in Turkey, as well as the location of the students who fled to Turkey from Egypt; the callers threatened these Uyghurs with arrest on Turkish soil.70Ibid. It is not only Uyghurs who are targeted as informants. One ethnic Turk, Can Uludag, told the Globe and Mail that he had been contacted in the summer of 2017 via Facebook and email and offered up to 500 U.S. dollars for information on the Uyghur community, and was told that that there were already others engaged in informing on the Uyghur community via email in Turkey.71VanderKilppe, Nathan (2017, October 29) “How China is targeting its Uyghur ethnic minority abroad” Globe and Mail Retrieved from https://beta.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/uyghurs-around-the-worldfeel-new-pressure-as-china-increases-its-focus-onthoseabroad/article36759591/?ref=http://www.theglobeandmail.com&

This has created an atmosphere of fear in the Uyghur community in Turkey, according to the diaspora member UHRP interviewed. A conference on Uyghur literature in Istanbul, which had attracted around one hundred attendees in previous years, was down to fewer than ten in 2017.72Interviewee B, Interview with Uyghur Human Rights Project 2017 According to the individual UHRP interviewed, virtually every member in the Uyghur community in Turkey has a relative who has been sent to the reeducation centers in East Turkestan. In April, Uyghurs in Turkey began to feel pressure to return from officials from their hometowns, and in June and July the pressure increased. Some Uyghurs living in Turkey decided to return home; one Uyghur chef working in a restaurant in Ankara returned and subsequently disappeared.73Ibid.

According to the individual interviewed by UHRP, in July the Chinese security officials who were involved in the detaining and deporting of Uyghur students in Egypt in the summer of 2017 had arrived in Turkey after a stop in Dubai. Thus far the Turkish government has not cooperated with deporting Uyghurs to China, but recently a Uyghur Canadian citizen was deported to Canada and the authorities searched the house of a local Uyghur activist.74Ibid.

Monitoring dissidents is likely to remain a prime concern for the Chinese government as repression worsens within China’s borders, but the above cases show that the Chinese government’s desire to maintain control over Uyghurs beyond its borders goes beyond those engaged in political activities. While Canadian national Erkin Kurban’s experience shows that the Chinese security services have not given up the strategy of attempting to recruit Uyghurs as spies while they are on Chinese soil, the Swedish and German cases suggest that they are increasingly confident in their intelligence operations overseas. Using threats against family members remaining within China remains one of the Chinese government’s most effective tools.

IV. Cases of Targeting Reporters, Activists and Students

North America, Europe, Australia and New Zealand

Retaliation against family members is one of the most common techniques that the Chinese authorities use in their attempts to silence overseas dissidents. It has been used against those the authorities perceive as threats for many years and it is by no means limited to Uyghurs. One recent example is the imprisonment of former Southern Weekend journalist Chang Ping’s siblings after he published an editorial in Deutsche Welle critical of Xi Jinping’s treatment of journalists.75Chang Ping: (2016, march 27) “My Statement About the Open Letter to Xi Jinping Demanding HisResignation” China Change Retrieved from https://chinachange.org/2016/03/27/chang-ping-my-statement-about-the-open-letter-to-xi-jinping-demanding-hisresignation/

This tactic long been used against those in the Uyghur diaspora who work to report on news related to the Uyghur issue and activists who seek to advocate for Uyghur rights. Chinese authorities often call overseas Uyghurs in an attempt to intimidate them into stopping their activism, often with their relatives present as leverage. This is what happened to Canadian citizen Mehmet Tohti in 2007. An official called him from Kashgar identifying himself as from the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office, and said that they had his mother and brother with them, having driven them hundreds of miles from their hometown of Kharghilik to Kashgar. His mother asked him to stop his political activities and the officers implied they could retaliate against his family members. He continued to receive similar calls, and even says that he has experienced intimidating incidents on Canadian soil, namely Chinese men sitting outside his house at night, which he reported to Canada’s intelligence service.76Gillis, Charlie (2007 May 7) “Beijing is Always Watching” MacLean’s Retrieved from http://archive.macleans.ca/issue/20070514 Attempts at intimidation have been reported in other countries as well; in 2009, Asgar Can, then Vice President of the World Uyghur Congress, told the German media that threatening calls had been made to the WUC’s offices, saying: “It will be for you like it is for Uyghurs in the homeland…We know where your office is.”77Kastner, Bernd, Maier-Albang, Monika, Ramelsberger, Annette, and Wimmer, Susi (2010, May 17) “Deutschland geht gegen chinesische Spione vor” Süddeutsche Zeitung Retrieved from http://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/razzien-deutschland-geht-gegen-chinesische-spione-vor-1.127920 It is not possible to ascertain whether this was an official action or not.

Applying pressure to family members and having them call their relatives abroad to push them to cease their political activities is one of the most common tactics used by the Chinese authorities. Kaiser Ozhun Abdurusul, president of UyghurPEN, told Swedish media in 2009 that his father had been called into a police station near Kashgar and shown surveillance photos of him and his wife in Sweden, as well as detailed information on his activities in Sweden.78Sadnin, Esbjorn (2009, October 10) “Flyktingspionage tystar uigurer i Sverige” Dagens Neyhetter Retrieved from http://www.dn.se/nyheter/sverige/flyktingspionage-tystar-uigurer-i-sverige/ Abdurusul’s father was told that unless his son ceased his political activities he would never get a passport to be able to see his son again. Abdurusul cut off contact with his family remaining in East Turkestan, fearing repercussions for them. This tactic is unfortunately often effective, one Uyghur activist told UHRP.79Dilshat Raxit Interview with Uyghur Human Rights Project 2017 Putting their relatives in danger while they are out of reach of the authorities in the West causes considerable guilt.

The experience of Ilshat Hassan Kokbore presents a classic case of this type of harassment taking place on U.S. soil. He had been known to the authorities since the 1980s due to his political activism, and fled East Turkestan in 2003. After settling in the U.S. in 2006, he became politically active in the Uyghur American Association, leading to serious difficulties for his family members who remained at home. His wife and son were not able to get passports, leaving them essentially hostages. He divorced his wife hoping this would end the authorities’ threats and surveillance, but it continued. One of his sisters was imprisoned for nearly a year without charge.80Kokbore I. (2016 May 24) Congressional Executive Committee on China “Written Statement of Ilshat Kokbore” Retrieved from https://www.cecc.gov/sites/chinacommission.house.gov/files/CECC%20Hearing%20- %20Long%20Arm%20-%2024May16%20-%20Ilshat%20Hassan%20Kokbore.pdf

Although the authorities have been known to use this tactic against those not politically active to pressure them to monitor their peers or to return to China, nevertheless it is those engaged in reporting potentially politically sensitive topics regarding events in East Turkestan who are most likely to be subjected to it. Though Uyghurs who are not politically active are pressured by authorities to monitor their peers or return to China, those who are engaged in reporting or activism are most frequently targeted. One prominent case is that of Shohret Hoshur, a journalist from Radio Free Asia who has managed to report on events taking place in East Turkestan despite the difficulty getting access to the region. Based in Washington D.C., Hoshur gets his information by calling into the region after an incident happens, although he assumes that all calls made into East Turkestan from overseas are recorded.81UHRP Interview with Shoret Horshur 2016 After 2012 to 2013, years with a large number of violent incidents, pressure on his family increased. One of his brothers was arrested and sentenced to five years imprisonment in a mass trial for disclosing state secrets. Two of his other brothers were detained after they spoke to him over the phone; they asked him to tell the world about their brother’s situation, to which he replied that they should be patient. The Global Times reported that Hoshur and his brothers were referencing terrorist attacks they were planning on carrying out, although they did not mention Horshur by name.82Ibid.

Hoshur told UHRP that these kinds of tactics are widely used on the families of Uyghurs who reside overseas, and are effective in causing Uyghurs to self-censor and be more cautious in their political activities. Those Uyghurs with relatives who have been harassed or imprisoned are reluctant to come forward and speak to the media or the authorities of the countries in which they reside for fear of worsening the situation. He said that he believes there is not much the international community can do to help.83Ibid.

Another tactic is to pressure governments to treat Uyghurs, especially those engaged in rights advocacy, as terrorists. These tactics go back to before the 9/11 terrorist attacks, although the Chinese state has increasingly pushed the narrative of Uyghurs as a terrorist threat in the years since. One frequent target of this is Dolkun Isa, the current General Secretary of the World Uyghur Congress. The Chinese government attempts to influence other nations into denying him entry, including through the use of the INTERPOL Red Notice system. He was flagged as a terrorist through the system, a fact he first became aware of in 1999, before the events of 9/11 increased China’s efforts to frame Uyghur activism as terrorism and when protections against abuses of the system by repressive regimes were particularly weak. He only became aware he was on the list when police in Germany held him after attempting to cross the border. The police verified his asylum status and determined that the Red Notice, issued in 1997, was illegitimate, but warned him against traveling to Asia. He was subsequently placed on a public list of terrorists that the Ministry of Public Security published in 2003.84People’s Daily (2003, December 16) “China issues a list of terrorists and organizations” Retrieved from http://en.people.cn/200312/15/eng20031215_130432.shtml

Since that time, he has been prevented from entering a number of countries, including Switzerland, South Korea, Turkey, and the United States. Requests to the U.S. Congress and U.S. State Department allowed him to be taken off the U.S.’s list of threats and obtain a visa, but other nations’ policies are less clear- he is uncertain, for instance, why he was barred from entering Turkey in 2008 after having made numerous trips in the past.85Dolkun Isa Interview with UHRP 2016 The incident in South Korea was perhaps most disturbing, as he was very concerned that he was in danger of refoulment to China.86Ibid. Having been detained at the airport for three days due to being flagged by the INTERPOL Red Notice, he was expelled from the country after intervention by EU authorities.

Isa’s ability to get a visa to enter a country became a political football in the case of India revoking his visa after initially granting him one to attend a conference in Dharamsala in 2016;87Henandez, Javier (2016, April 25) “Uighur Activist in Germany Sees China’s Hand in Revocation of Indian Visa” New York Times Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/26/world/asia/uighurindia-china-visa.html?_r=1 many observers saw the initial granting of his visa as retaliation for China blocking an attempt by members of the UN to designate the founder of a Kashmiri militant group as a terrorist,88Pant, Harsh V. (2016 April 28) The Dolkun Isa Visa Affair: India Mishandles China, Once Again” the Diplomat Retrieved from http://thediplomat.com/2016/04/the-dolkun-isa-visa-affair-india-mishandleschina-once-again/ a move illustrative of the political nature of China’s use of the ‘terrorist’ label. Omer Kanat, then Vice President of the World Uyghur Congress was also informed that his Indian visa was canceled as he prepared to travel to Dharamsala.

The Red Notice system has for most of its existence been opaque. In 2010 Mr. Isa requested access to his file and it took two years for the Commission for Control of INTERPOL’s Files (CCF) to respond. INTERPOL requires the permission of the country that posted the information to make it public; the Chinese did not permit the CCF to confirm whether there was one.89Fair Trials International (2013, November) “Strengthening Respect for Human Rights, Strengthening INTERPOL” Retrieved from https://www.fairtrials.org/wp-content/uploads/Strengthening-respect-forhuman-rights-strengthening-INTERPOL5.pdf In 2015, INTERPOL reformed the Red Notice system in an effort to prevent its use against refugees and asylum seekers, but the appointment of the Chinese Vice Minister of Public Security Meng Hongwei as president of the organization has raised concerns. A recent push by INTERPOL to share biometric data of terrorist suspects also has the potential for misuse.90INTERPOL (2016 November 9) “Biometric Data on Terrorists Needed to Activate Global Tripwire” Retrieved from https://www.interpol.int/News-and-media/News/2016/N2016-147 China has increased its issuing of Red Notices as its anti-corruption campaign takes on an international character and it pursues suspects overseas, but the political nature of the way China uses the system is likely to undermine its use as a tool for in pursuing legitimate criminal suspects.

The Chinese authorities continue to try to paint Mr. Isa and other Uyghur activists as terrorists. Before China’s Universal Periodic Review in 2013 the Chinese Mission to the United Nations in Geneva circulated allegations about Mr. Isa’s involvement in terrorism to the press.91Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (2013, October 5) “PR China Keen on Silencing Human Rights Critics during Universal Periodic Review” Retrieved from http://unpo.org/article/16523 The Chinese delegation frequently tries to disrupt Uyghur advocacy at the UN. It tries to bar Dolkun Isa and Rebiya Kadeer from the UN Human Rights Council on the grounds that they have evidence that they are connected to terrorist activity,92Wee, Sui-Lee and Nebeyhay, Stephanie (2015, October 6) “At U.N China uses intimidation tactics to silence its critics” Reuters Retrieved from http://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/chinasoftpower-rights/ and otherwise disrupts their participation. During the WUC’s speech at the 9th UN Forum on Minority Issues in 2016, China objected on a point of order, leading to twenty minutes of discussion of the WUC’s right to speak, supported by Austria, Finland, Ireland and Switzerland and opposed by Iran, Russia, Egypt, Pakistan, Cuba, Venezuela, Bolivia and Indonesia.93World Uyghur Congress (2016, December 1) “World Uyghur Congress Confronts Obstacles at UN Forum on Minority Issues” Retrieved from http://www.uyghurcongress.org/en/?p=30408 Isa was escorted out of the UN Human Rights Committee Session in Geneva in 2007, and most recently in May 2017 was forced to leave a meeting of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues in New York.94Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (2017, May 8) “Uyghur Human Rights Activist Expelled from UNPFII” Retrieved from http://unpo.org/article/20072 In July of 2017 local police prevented him from entering the Italian Senate and detained him at the request of China, according to the officers.95Reuters (2017, July 28) “Exiled Uighur group condemns Italy’s detention of its general secretary” Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-italy-xinjiang/exiled-uighur-group-condemnsitalys-detention-of-its-general-secretary-idUSKBN1AD16Z In response several members of the Italian Parliament requested clarification on who requested Mr. Isa be detained and what steps the Italian authorities were taking to ensure that the Red Notice system was not being abused.96Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (2017, August 8) “Italian Politicians Inquire About Uyghur HR Activist Detainment” http://unpo.org/article/20263

In 2006, the Bavarian Green Party asked Bavarian authorities to investigate whether the Chinese were reading their emails and the extent to which Chinese intelligence was active in Munich.97Die Grünen im Bayerische Landtag (2006, November 24) “Bespitzelt chinesischer Geheimdienst die Grünen?” Retrieved from http://www.thinkyoung.de/themen/bespitzelt-chinesischer-geheimdienst-diegruenen In November of that year Chinese Consul General Yang Huiqun visited their offices in the Bavarian state parliament. He showed them invitations from the WUC and a list of members who were intending to meet with WUC delegates which had only been circulated via private e-mail between the MPs and the WUC. When asked where he got the list he replied that “the Consulate had ‘its own information channels.’”98Gesellschaft für bedrohte Völker (2009, November 26) “China’s defamation campaign against Uighur human rights activists began six years ago – German government must take action!” Retrieved from https://www.gfbv.de/en/news/chinas-defamation-campaign-against-uighur-human-rights-activists-begansix-years-ago-german-government-must-take-action-4566/ The Consul urged them not to meet with the activists, saying they were terrorists who were under observation by the BfV. The BfV said that the WUC was in fact not under investigation, and that the Chinese had asked them to ban the event as well.

Another case of a politically active Uyghur experiencing issues with freedom of movement is that of Umit Hamit Agahi. He travelled to Hungary in 2013 as VicePresident of the World Uyghur Congress leading a youth delegation to meet with youth members of the World Federation of Hungarians. Police went to the hotel where the delegation was staying and checked the papers of all the members then shut down the hotel alleging a fire code violation. Umit Hamit was detained by police and for twelve hours and interrogated on suspicion of being a terrorist. When the youth delegation went to the headquarters of the World Federation of Hungarians it was shut down by police, allegedly due to a bomb threat. As a German citizen, he has a right to travel freely in EU countries, but was expelled from the country along with the rest of the delegation. He suspects that China alerted the Hungarian authorities and accused Hamit of being a terrorist, but it is unclear through what channel they did so.99Radio Free Asia (2013 March 1) “Hungary Clamps Down on World Uyghur Congress Meeting, Expels Official” Retrieved from http://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/hungary-06012013164736.html Police initially said that Umit would was barred from retuning to Hungary, but a local court determined that their actions were illegal and Hamit returned to hold a press conference on the issue. The Chinese government has also attempted to block Uyghur activism abroad by protesting events held by Uyghur activists.

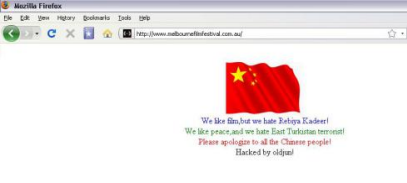

The Chinese consulate in Melbourne requested that a documentary about the life of Rebiya Kadeer be withdrawn from the Melbourne International Film Festival and her visa revoked. The Australian government and festival organizers refused the requests and the showing of the film went forward. The festival’s website was hacked, the film schedule replaced with Chinese flags and anti-Kadeer slogans. Though it is not possible to determine whether or not this was coordinated by the Chinese authorities, but the director of the film believed that the abusive emails he was subjected to were part of a coordinated strategy.100Tran, Mark (2009 July 6) “Chinese Hack Melbourne Film Festival Site to Protest at Uighur Documentary” The Guardian Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/jul/26/rebiyakadeer-melbourne-film-china Chinese filmmakers who had entries in the festival pulled them out but denied that there was pressure from their government to do so. China also applied pressure to New Zealand, attempting to prevent the film from being broadcast on the Maori Television channel and eventually convinced the broadcasting station to show a Chinese government made documentary on the 2009 unrest in Urumqi, albeit with a disclaimer.101Gay, Edward (2009 September 9) “Maori TV to show Chinese Govt video after Kadeer documentary” New Zealand Herald Retrieved from http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10594528

The Melbourne International Film Festival’s website after hack © Australian Film Review Chinese embassies engage with overseas Chinese communities and attempt to influence opinion among them, and even on occasion organize them. Bodies like the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office exist for this very purpose, and embassies’ education departments serve as another means of recruiting informers, according to Chen Yonglin, a staff member of the Chinese embassy to Australia who alleged that the embassy cultivated 1,000 informers among the overseas Chinese students.102Garnaut, John (2014 April 21) “Chinese spies at Sydney University” The Sydney Morning Herald Retrieved from http://www.smh.com.au/national/chinese-spies-at-sydney-university-20140420- 36ywk.html#ixzz2zTGp87fi In 2010 Richard Fadden, then Director of Canada’s counterintelligence service CSIS, gave a speech at the Royal Canadian Military Institute describing activities conducted by the Chinese embassy in Canada: “They’re funding Confucius institutes in most of the campuses across Canada…They’re sort of managed by people who are operating out of the embassy or consulates. Nobody knows that the Chinese authorities are involved. …They’ve organized demonstrations to deal with what are called the five poisons: Taiwan, Falun Gong, and others.”103House of Commons, Canada 40th Parliament, 3rd Session (2011, March) “Report on Canadian Security Intelligence Service Director Richard Fadden’s Remarks Regarding Alleged Foreign Influence of Canadian Politicians: Report of the Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security” Retrieved from http://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/403/SECU/Reports/RP5019118/securp08/securp08-e.pdf

Uyghurs naturalized as citizens of other countries sometimes have difficulty obtaining visas to China. James Millward, a professor of Chinese history at Georgetown University, said in an interview that he was aware of a Uyghur-American student who had won a scholarship to study in China from her Confucius Institute-sponsored Chinese language class but was denied a visa to study in China, alone among a group of students.104Sinica Podcast (2017, October 5) “Alarm bells in the ivory tower: Jim Millward on the Cambridge University Press censorship fiasco” Supchina Retrieved from http://supchina.com/podcast/alarm-bells-ivorytower-jim-millward-cambridge-university-press-censorship-fiasco/

The Chinese embassy uses student groups such as the Chinese Students and Scholars Association to organize protests, and to monitor Chinese students involvement in sensitive issues such as human rights.105Baker, Richard, Koloff, Sashka, Mckenzie, Nick, and Uhlmann, Chris (2017, June 4) “The Chinese Communist Party’s power and influence in Australia” ABC Four Corners Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-06- 04/the-chinese-communist-partys-power-and-influence-in-australia/8584270 The 2008 Olympic torch relay was an example of this type of embassy-sponsored protest. While the counter-protestors at the Olympic torch relay in 2008 were likely motivated to some degree by genuine patriotism, Chinese embassies and consulates encouraged and organized them. In Canberra, Tibetan and Uyghur protestors clashed with Chinese counter-protestors, leading to police intervention. The student-led counter-protest group had received support from the Chinese embassy, including free travel and accommodations.106Garnaut, John, Li, Maya, and Nicholson, Brendan (2008 April 16) “Students plan mass torch defense” The Age Retrieved from http://www.theage.com.au/news/national/students-plan-mass-torchdefence/2008/04/15/1208025189581.html The Chinese government puts pressure on institutes of higher education as well; after initially inviting Rebiya Kadeer to speak at Auckland University in New Zealand, the school revoked her invitation due to security concerns, a move the student association president attributed to the institution’s financial reliance on Chinese students.107Tan, Lincoln (2009 October 10) “Activist to face Chinese Protests” New Zealand Herald Retrieved from http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10602379 Kadeer was re-invited by one of the institution’s law lecturers and the event went ahead as planned.108Otogo Daily Times “Chinese dissident Re-invited to Auckland Uni” Retrieved from https://www.odt.co.nz/news/national/chinese-dissident-re-invited-auckland-uni

Pressure on Uyghur Students Studying Abroad

In early May 2017, Uyghur students studying abroad in multiple countries including France, Australia, the United States, Egypt and Turkey were ordered by Chinese authorities to return their hometowns by May 20th. A police officer in Payziwat county, Baren township told Radio Free Asia that the policy had been ordered by the regional government and was intended to “identify their political and ideological stance, and then educate them about our country’s laws and current developments.”109Radio Free Asia (2017, May 9) “Uyghurs Studying Abroad Ordered Back to Xinjiang Under Threat to Families” Retrieved from http://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/ordered-05092017155554.html The police officer mentioned that only the Uyghur students had been ordered to return home, suggesting that suspicions about Uyghurs’ political stance have spread beyond those who seek asylum and that efforts at monitoring and controlling them are escalating. Once again, threats toward family members were used to obtain the students’ compliance, with some returning because their parents and siblings were being detained. Uyghurs studying abroad in Canada were too afraid of the possible consequences to their families to report this pressure to the government or media, according to Rukiye Turdush, a Uyghur Canadian activist.110VanderKilppe, Nathan (2017, October 29) “How China is targeting its Uyghur ethnic minority abroad” Globe and Mail Retrieved from https://beta.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/uyghurs-around-the-worldfeel-new-pressure-as-china-increases-its-focus-onthoseabroad/article36759591/?ref=http://www.theglobeandmail.com& One student studying in the United States was allowed to return after speaking to the police in his hometown of Baren.111Radio Free Asia (2017 May 9) “Uyghurs Studying Abroad Ordered Back to Xinjiang Under Threat to Families” Retrieved from http://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/ordered-05092017155554.html A government official was specially assigned to speak to the parents of Uyghur students studying abroad, telling them “to advise their children so that they don’t go astray and don’t take part in any antiChina activities.”112Ibid. Uyghur students studying in Japan contacted UHRP stating that in April they also began experiencing pressure from the authorities to return to their hometowns. Family members called them and told them they were required to return. One individual reported being interrogated about the Uyghur community in Japan, and was placed in political training. The whereabouts and situation of others who returned from Japan are not known, according to information obtained by UHRP.

The pressure on students studying in Egypt was particularly intense, and began in January of 2017.113Ibid. A Uyghur al-Azhar student told Reuters that pressure on students’ families had begun last year, saying “Some of us were asked, under pressure, to go back to China, by force applied to their families…Some of my fellow students returned, some remained in Egypt and some fled in fear to surrounding countries like Turkey.”114Barrington, Lisa (2017, Jul 7) “Egypt detains Chinese Uighur students, who fear return to China: rights group” Reuters Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-egypt-china-uighur-idUSKBN19S2IB In July 2017 Egyptian security forces detained and deported those who did not return voluntarily. Egyptian aviation officials told the media that they had been ordered by the Egyptian police to put at least 22 Uyghur individuals on flights to China on July 6th.115Youssef, Nour (2017, July 6) “Egyptian Police Detain Uighurs and Deport Them to China” New York Times Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/06/world/asia/egypt-muslims-uighursdeportations-xinjiang-china.html?_r=0

The previous month the Egyptian Interior Ministry and the Chinese Ministry of Public Security had signed a “technical cooperation document” in a meeting that “dealt with issues of common concern,” although the details of the subjects discussed were not made public.116Egyptian State Information Service (2017, June 20) “Egypt, China sign technical cooperation document in specialized security fields” Retrieved from http://www.sis.gov.eg/Story/114496?lang=en-us Police raided several Uyghur restaurants in Cairo, and Uyghur activists alleged that police were searching for Uyghurs at their places of residence as well.117Al Jazeera (2017, July 7) “Egypt arrests Chinese Muslim students amid police sweep” Retrieved from http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/07/fear-panic-egypt-arrests-chinese-uighur-students170707051922204.html Al-Azhar University denied that students had been detained on campus, while Egyptian state reported that officials were denying that Uyghurs were being targeted, saying they were expelling individuals without valid visas.118Baghat, Farah (2017, July 10) “Security official denies “targeting” Uyghur students in Egypt” Daily News Egypt Retrieved from https://dailynewsegypt.com/2017/07/10/security-official-denies-targetinguyghur-students-egypt/ However, Uyghurs who spoke to RFA said that individuals with valid visas were also being deported.119Radio Free Asia (2017, July 7) “Uyghur Students in Egypt Detained, Sent Back to China” Retrieved from http://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/students-07072017155035.html On July 19th 2017, local activists reported that the detained students had been moved by the Egyptian Ministry of the Interior to a prison in Cairo, where they were being interrogated by both Egyptian and Chinese officials;120Rohan, Brian (2017, July 19) “Uighur activists say detained students moved to Cairo prison” Washington Post Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/uighur-activists-saydetained-students-moved-to-cairo-prison/2017/07/19/589e3606-6c8b-11e7-abbca53480672286_story.html?utm_term=.7d87798b1738 among those interrogating the students was the head of the Chinese Students and Scholars Association in Egypt, according to several students who were later released.121RFA (2017, October 30) “Nearly 20 Uyghur Students Unaccounted For Four Months After Egypt Raids” Retrieved from http://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/students-10302017162612.html Ultimately over two hundred Uyghurs were detained and several dozen deported to China; approximately eighty are believed to still be in detention, with another sixteen still unaccounted for.122Ibid.

Central Asia