A Uyghur Human Rights Project report by Henryk Szadziewski. Read our press statement on the report here, and download the full report here.

I. Summary

The human rights crisis in East Turkestan (also known as the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region) requires an urgent international response. The mass internment of Uyghurs in camps across the region is occurring as the Chinese government promotes itself globally as a model of governance and trade through the Belt and Road Initiative. Over a million Uyghurs have been interned out of a population of 11 million. Credible reports of deaths in custody, torture, and systemic political indoctrination must propel the international community into action on behalf of the Uyghurs. For several years, human rights conditions have deteriorated for Uyghurs with little prospect of relief. Political repression, economic marginalization, curbs on religious practice, demographic engineering, and Sinification have been extensively documented by a broad range of actors. Timing is key in human rights interventions to ensure the collective long-term welfare of vulnerable groups, and the time to publicly seek accountability from China regarding the mass-internment of Uyghurs is now.

The international community should call on China to immediately release all those being held without charge in internment camps. It has several instruments with which to bring China to account over the system of internment camps in East Turkestan. The first is the use of United Nations (UN) processes. China’s Universal Periodic Review in November 2018 should be leveraged to make Chinese officials answer questions on the internment camp system aimed at “solving” the Uyghur problem. China’s bid to shape the rights agenda in multilateral settings should be challenged with a robust defense of political and civil rights at the UN. The second mechanism available to states is to adopt a form of “Global Magnitsky Act.” Such acts are global in scale and can be used to sanction Chinese officials complicit in the human rights violations occurring in East Turkestan. The freezing of assets and exclusion from banking systems overseas are within the power of concerned governments. The third measure is to end forced returns of Uyghurs due to Chinese government pressure. Uyghurs who have resided abroad or who have some overseas connection have been forcibly disappeared into internment camps. Given the probability of internment based on ethnicity, there is no reason Uyghurs peaceably living overseas should be returned to China.

Since the spring of 2017, the Chinese government has been systematically interning Uyghurs in camps. While the intention of the camps remains undisclosed, reports of repetitive political indoctrination, Sinification through Chinese language and culture sessions, and compulsory denunciations of Uyghur culture and belief in Islam indicate the Chinese authorities are aiming to forcibly assimilate Uyghurs. As Beijing prepares to situate East Turkestan as the fulcrum of Xi Jinping’s signature Belt and Road Initiative policy, China is attempting to find a solution to the problem of the Uyghurs’ distinctive belief in Islam and Turkic identity. The effort to alter the Uyghurs’ identification with perceived ‘external’ allegiances is China’s final colonial act in a territory it has plundered and settled while purposefully excluding Uyghurs from the benefits of their homeland.

This report documents the camp system, examining the scale of the facilities, as well as the reported conditions and detainee numbers. To elevate the voices of Uyghurs impacted by the internment camps, the next section of the report presents a synthesis of primary and secondary sources. Uyghurs with experience inside the camps spoke to UHRP, and those testimonies have been added to existing accounts in the international media. Furthermore, UHRP interviews with Uyghurs whose relatives and friends have disappeared into the camps are included along with publicly available sources of similar narratives. The intention is to demonstrate the distress the internment camps have created at a human scale. UHRP found no Uyghur is safe from the camps: students, farmers, store keepers, religious figures, artists, soccer players, local government workers, women, men, children, teenagers, the elderly are among the interned. An indication of China’s aim to suppress information of the camps is seen in the targeting of relatives of Radio Free Asia Uyghur Service reporters.

The impacts of the camps and cumulative repressive policies on generations of Uyghurs will be profound. The Chinese government has signaled a clear shift from rhetoric claiming respect for ethnic minorities to forcible assimilation in internment camps and criminalization of ethnic identity, as well as religion. Observers have compared the camps to Soviet Gulags,1Nordlinger, J. (2018). China’s Uyghur Oppression: A New Gulag. [online] National Review. Available at: https://www.nationalreview.com/magazine/2018/05/28/china-uyghur-oppression-new-gulag/[Accessed 30 Jul. 2018]. and in a May 20, 2018 editorial, the Washington Post wrote: “All who believe in the principle of ‘never again’ after the horror of the Nazi extermination camps and Stalin’s gulag must speak up against China’s grotesque use of brainwashing, prisons and torture.”2Washington Post (2018). China’s repugnant campaign to destroy a minority people. [online] Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/chinas-repugnant-campaign-to-destroy-a-minoritypeople/2018/05/20/9fe061b4-5ac0-11e8-b656-a5f8c2a9295d_story.html?utm_term=.e378b77a3b15[Accessed 30 Jul. 2018]. In his July 2018 testimony before the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, scholar Rian Thum stated that in the absence of due process in the camps: “We cannot rule out the possibility of mass murder.”3Congressional-Executive Commission on China (2018). Hearing on Surveillance, Suppression, and Mass Detention: Xinjiang’s Human Rights Crisis. [online] CECC. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rE8Ve2nxPds [Accessed 30 Jul. 2018].

Uyghur youth has been a focus for the Chinese authorities. Before the forced returns of Uyghur students overseas and arbitrary detention in internment camps, young Uyghurs were already prohibited from speaking their own language in schools and universities, sent outside the region for a secondary education, denied employment, prevented from entering mosques, and forcibly disappeared in security sweeps. The latest phase of the internment campaign has seen a large build-up of orphanages to which Chinese authorities are sending Uyghur children with one or both parents in camps. In an environment where state-led racial profiling, harassment and violence is endemic, the future for the next generations of Uyghurs remains bleak. A further escalation of tactics of repression also cannot be ruled out, raising the specter of human-rights violations of an even graver nature in the near term

II. Background

The current situation in East Turkestan is without precedent in post-Mao China and has invited comparisons to the Cultural Revolution, as well as regimes such as apartheid South Africa. Since Chen Quanguo took up the post of Party Secretary of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) in 2016, there has been a massive expansion of the security forces, as well as a propaganda campaign aimed at accelerating the forcible assimilation of the Uyghur people into a homogenous Chinese identity. Assigning Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials to stay in the homes of Uyghurs to explain the laws and beneficence of the Party, weekly or daily flag raisings, Mandarin classes for all ages, and more aggressive confiscations of Qurans and other religious objects are part of a campaign of which the so-called re-education camps are the most extreme manifestation.

In Spring 2017, it first became apparent that the repression of the Uyghur people was entering a new phase. Uyghur students studying abroad in countries across the world were being contacted by the authorities in their hometowns and ordered to return for political assessment by May 20.4Hoshur, S. (2017) Uyghurs Studying Abroad Ordered Back to Xinjiang Under Threat to Families [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/ordered-05092017155554.html The wellbeing of their relatives was used as leverage to ensure they complied. By the autumn, reports emerged that thousands of Uyghurs were being detained in so-called “reeducation camps.”

These camps exist outside of the formal legal system, but have grown to a massive size, possibly holding as many as one million people, or 10% of the Uyghur population. There are a variety of terms used in official documentation for these facilities. One of the most common is centralized re-education training centers (集中教育转化培训中心). Although the word 集中 can be translated as either “centralized” or “concentrated/to concentrate” this report will refer to these facilities not as concentration camps, nor re-education camps reflecting their official name, but rather internment camps. This term suggests their nature as extra-judicial detention centers holding a broad cross-section of the population, including men and women of all ages and even reportedly some children.

Thus far there has been little in the way of official acknowledgement of the camps by the Chinese government. The media attention the issue has been getting in Kazakhstan led the Ambassador in Almaty to accuse those protesting “the so-called problems of ethnic Kazakhs in Xinjiang” of attempting to interfere in China’s internal affairs.5Feng, Emily (2018) Kazakh trial throws spotlight on China’s internment centres [online] Financial Times. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/17b12756-93dc-11e8-b67b-b8205561c3fe[Accessed 22 Aug. 2018] The Chinese government has skillfully prevented reporters from being able to investigate the situation on the ground both by restricting their access and threats to any possible sources. Uyghurs who discuss the experiences of themselves or their relatives are placing themselves and their families in danger. The targeting of Uyghurs with any overseas connection has cut off the Uyghur diaspora from their friends and family back home, meaning many cannot get information on their family members’ wellbeing.

This also means that beyond the disappearances of many Uyghurs and the testimonies of those who have managed to flee to safety, much of the evidence of the camps has come from indirect sources and the few hints that have appeared in the official media, although many Chinese media reports mentioning the camps have been deleted from the internet. One scholar, Adrian Zenz, has gathered a large amount of evidence from Chinese government tenders for constructing and equipping the camps, as well as recruitment notices for staffing them. He argues this evidence demonstrates “the PRC government’s own sources broadly corroborate some estimates by rights groups of number of individuals interned in the camps.”6Zenz, A. (2018). New Evidence for China’s Political Re-Education Campaign in Xinjiang [online] Jamestown Foundation Available at: https://jamestown.org/program/evidence-for-chinas-political-re-education-campaign-inxinjiang/ Accessed 22 Aug. 2018].

The Re-education Campaign Emerges from “De-extremification”

“Re-education” has a long history in China, although utilizing it against the Uyghurs on such a large scale is unprecedented, at least since the end of the Cultural Revolution. “Reeducation through labor” camps date back to the 1950s, but the term most often used for the program to “re-educate” Uyghurs, jiaoyuzhuanhua (教育转化), literally “transformation through education,” was first used on practitioners of Falun Gong. Amnesty International described a process in which detainees “attend daily, often lengthy, “study sessions” where they are required to publicly criticize their own behavior, accept criticisms from others, study CCP documents, directives and relevant political doctrine, and generally demonstrate their submissive and cooperative attitude to camp authorities. These “thought work” and “study sessions” often require detainees to express their political loyalty to the CCP and to express their thanks and appreciation to the CCP for its “concern” and “care” of their situation.”7Amnesty International (2013). Changing the soup but not the medicine? Abolishing Re-education Through Labour in China [online] Amnesty International. Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/12000/asa170422013en.pdf [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. In many ways this matches first-hand descriptions of what is going on inside the camps in East Turkestan.

This re-education campaign represents the ideological side of the government’s securitization strategy, paralleling the massive buildup of a high-tech police force. The ideological campaign is referred to as “de-extremification,” a term first used by the previous XUAR Party Secretary Zhang Chunxian at a Party meeting in Hotan in 2011.8边驿卒 (2016). 张春贤治疆6年:推动去极端化 禁公共场所穿蒙面罩袍 [online] 凤凰资讯 Available at: http://news.ifeng.com/a/20160829/49857500_0.shtml [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. At the Second Xinjiang Work Forum in 2014, Xi Jinping declared that “religious extremism is the foundation of Xinjiang ethnic splitism,” and therefore a great danger to Chinese national security, calling for the launch of “de-extremification” work.9白丽 (2017) . 去极端化条例颁布实施意义重大 [online] 新疆日报Available at: http://theory.gmw.cn/2017- 04/14/content_24204140.htm [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. The national level counter-terrorism law adopted in 2015 calls on relevant government departments to undertake education and propaganda,10第十二届全国人民代表大会常务委员会 (2015). 授权发布:中华人民共和国反恐怖主义法 [online] 新华社 Available at: http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2015-12/27/c_128571798.htm [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. as does the XUAR regional implementation guidelines.

In a 2014 meeting of the XUAR National People’s Congress and the Chinese People’s Consultative Congress it was declared that “solving ideological problems with ideological means” was one of the “five keys” to de-extremification.11最后一公里 (2015). “五把钥匙”如何治疆?[online] 人民网 Available at: http://sh.people.com.cn/n/2015/0420/c369653-24566405.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. The government promulgated lists and organized study sessions of signs of religious extremism, such as the 2014 list of 75 signs of extremism.12观察者网 (2014). 新疆部分地区学习识别75种宗教极端活动 遇到可报警 [online] 中国社会科学网 Available at: http://www.cssn.cn/zjx/zjx_zjsj/201412/t20141224_1454905.shtml Police distributed brochures about the list, encouraging citizens to report anyone exhibiting one of the signs.13Cao Siqi (2014). Xinjiang counties identify 75 forms of religious extremism [online] Global Times. Available at: http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/898563.shtml [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. At a stability work meeting in 2015, then-Party Secretary Zhang Chunxian announced that “the striking hand must be hard, and the educating hand must also be hard,”14新疆日报 (2015). 新疆自治区党委召开稳定工作会议 [online] 中国政府网 Available at: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2015-01/09/content_2802432.htm [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. a phrase which became common in the campaign (打击的一手要硬、教育疏导的一手 也要硬.)

Government officials appear convinced that there are large numbers of individuals among the Uyghurs who are “brainwashing” others and trying to convince them to commit violence. In a 2015 interview with Hong Kong media outlet Fenghuang, the Party Secretary of the XUAR Justice Department Zhang Yun (新疆司法厅党委书记张云) said that among those influenced by religious extremism in one village, 70% were swept up into religious extremism, 30% were contaminated by religious extremism, and a smaller number were already guilty of crimes or planning terrorism.15陈芳 (2015). 独家重磅:新疆去极端化调查 [online] 凤凰网Available at: http://news.ifeng.com/mainland/special/xjqjdh/ [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. He went on to say that the 70% would easily change if their environment was changed, the 30% required concentrated education work, and the last needed to be firmly attacked. In the same report, the secretary of the Hotan County Political and Legal Committee said that there were 5% in the “obstinate group,” 15% were fellow travelers, and 80% blind followers. As Adrian Zenz points out, these are similar to the numbers of people reportedly detained in the internment camps, suggesting the possibility that quotas have been implemented.16Zenz, A. (2018). “Thoroughly Reforming them Toward a Healthy Heart Attitude” China’s Political Re-Education Campaign in Xinjiang [online] Available at: https://www.academia.edu/36638456/Thoroughly_Reforming_them_Toward_a_Healthy_Heart_Attitude– _Chinas_Political_Re-Education_Campaign_in_Xinjiang [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018].

During the early part of the campaign, the government focused de-extremification education on specific groups: prisoners and detainees, those influenced by “religious extremist thought,” and rural people deemed likely to engage in violent terrorism.17陈芳 (2015). 独家重磅:新疆去极端化调查 [online] 凤凰网 Available at: http://news.ifeng.com/mainland/special/xjqjdh/ [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. People targeted or monitored by the government were referred to as “focus persons” (重点人)or persons in the “groups of special concern” (特殊群体). The government had been concerned to fix what were perceived to be weaknesses in village level government. They established the “three in one” mechanism made up of grassroots cadres, “Visiting, Benefiting and Gathering” (访惠聚) Party member teams, and local police offices.188 陈芳 (2015). 独家重磅:新疆去极端化调查 [online] 凤凰网http://news.ifeng.com/mainland/special/xjqjdh/ This mechanism appears to be that which is carrying out much of the re-education work, including examining Uyghur’s ideological stance, determining whether they will be sent to the camps. Cadres are assigned to the households of Uyghurs who have family members in the camps. In 2017, one Uyghur woman in Lop County, Hotan Prefecture, said that she and her four children had no income because her husband was in re-education.199 新疆洛浦(2017) 洛浦县:亲人帮助暖人心 汉维团结一家亲 [online] 新疆洛浦 Available at: http://www.xjluopu.com/Item/Show.asp?m=1&d=3359 [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. “Family members,” cadres from the local Bureau of Land and Resources, were assigned to visit her weekly, bringing food and a small amount of money. For this she thanked the Party and its “good policies,” and for finding her an “excellent Han relative.”20Ibid.

A 2014 regional People’s Congress work team (地区人大工委组织) conducted an inspection tour of Turfan to investigate the de-extremification work there. The work report, now available only on a mirror website, states that 3,152 people in special interest categories were identified – 760 veiled people, 971 bearded people, 1,388 jilbab wearers and 33 people who wore clothing with a crescent. Out of this, the report claimed, 3,087 had been re-educated, a success rate of 97.9 %. The report called for strengthening the training of those not yet re-educated and stated that numerous cities had established re-education training classes for the special groups. It advocated that for the minority “more stubborn in their thinking, focus on ‘breaking down the barriers in the heart, advance transformation in thinking.’” People “stubborn in their thinking” should also be subjected to 24 hour “accompaniment style” “one on one” mentoring-method centralized training. The centralized training should be combined with tracking after release to ensure the transformation was genuine. 21蒋新 (2014). 关于对落实《维护稳定21条禁令》和重点人群特殊群体“去极端化”教育转化工作专题调研的 报告 [online] Available at: http://8gecn.com/html/index..info545870952.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018].

It was also in 2014 that reports began to appear of people being re-educated for limited periods in closed settings. Some localities such as Ghulja established a system separating people into 4 classes labeled A through D. Class A, detained persons, and Class B, “people with obstinate thinking” were trained by the county Political and Legal Affairs Commission for 20 and 15 days respectively. Class C, “focus persons with unstable thoughts and groups of interest influenced by religious extremist thinking” and Class D, “people who could be influenced by religious extremist thinking” were trained for seven days by township and village organizations.22亚心网 (2015). 分类施策标本兼治伊宁县营造“去极端化”宣传教育威猛声 [online] 凤凰网 Available at: http://news.ifeng.com/a/20150114/42926321_0.shtml[Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. The media compared this targeted re-education to “drip irrigation.” Targets of the re-education campaign are also officially referred to as the “three types of people.” In Yitimliqum village in Kargilik County, local cadres were rewarded with 500 yuan if they discovered and sent the three types of people to re-education, but would be demoted if the three types were discovered in the village more than three times.23马登朝 (2014) 叶城县依提木孔乡采取“七大抓手”去极端化取得明显成效[online] 新疆兴农网 Available at: http://www.xjxnw.gov.cn/c/2014-08-25/737366.shtml [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. The 2014 report stated 112 people had been discovered, and after having been re-educated, 75 women had removed their veils, three had removed the jilbab, and 34 men had shaved their beards. Moreover, 36 other individuals had been reeducated. In addition to closed style re-education, the village established “masses service centers,” offering free wedding and funeral services.

The process of creating the re-education system involved the creation of dedicated facilities. One 2014 news report described a three-tier county-township-village “re-education base” system set up in Kashgar Konasheher County.24天山网 (2014). 新疆疏附三级教育转化机制推进“去极端化 [online] 凤凰网 Available at: http://news.ifeng.com/a/20141118/42504518_0.shtml [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. Those who resisted reeducation would be sent to the higher level “bases” while those who complied would be sent to the lower levels and gradually released back into village life. The article described women undergoing reeducation at a village’s “reeducation base.” A work team had been sent to the village due to its “religious atmosphere” and selected women wearing religious attire for re-education. One woman said that the security forces had detained her husband due to “religious extremist thoughts;” she expressed hope that he could be re-educated so they could be reunited. By November 2014, 3,515 had been trained in the three-tier system out of which 3,096 had been successfully “reeducated.”

In September 2015, the former Secretary of the Discipline Inspection Committee visited a “de-extremification education training center” in Hotan with the capacity to train 3,000 people influenced by “religious extremist thought.”25符强 (2015). 喀什和田经济发展蓬勃向上 [online] 新疆日报Available at: http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2015/0917/c398213-27598576.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. According to a media report, they were being trained in government policy, ethnic unity, received psychological counseling and engaged in writing activities to transform their character and re-educate them. The report said that they additionally received two months of training to increase their technical skills. The center had already gone through five cycles, and according to the former secretary those trained were no longer were influenced by “religious extremist thought infiltration,” and voluntarily preached to others.

The Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (Bingtuan) also ran reeducation centers at this time, for example a Legal System Education Training School run by the Third Division in in Payzivat County in 2015.26張騁 (2015). 法制教育培訓學校正式開課 [online] 新疆兵團廣播電視台 Available at:

https://kknews.cc/education/9m56n5l.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. Teachers were drawn from the Political and Legal Affairs Office, the United Front Work Department, local police stations, grassroots propaganda teams, and retired cadres. The school’s purpose was to centralize the correction of illegal religious activities, manage illegal marriage behavior, and “carry out collective education of stubborn, incorrigible people in cults.”27Ibid. Re-educating the students and make them love the country and the Party was accomplished by military-style lessons in law, government policy, flag raisings, singing the anthem, dancing to the pop song “Little Apple,” and military drills.

After Chen Quanguo took office in 2016 this re-education campaign expanded and became more systematized. In 2017, the “Xinjiang De-extremification regulations” (新疆维吾 尔自治区去极端化条例)28天山网 (2017) . 新疆维吾尔自治区去极端化条例[online] 博尔塔拉政府网 Available at:

http://www.xjboz.gov.cn/info/1799/158693.htm (Accessed 22 Aug. 2018). (unofficial translation available at China Law Translate)29China Law Translate (2017). Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Regulation on De-extremification [online]China Law Translate. Available at: https://www.chinalawtranslate.com/%E6%96%B0%E7%96%86%E7%BB%B4%E5%90%BE%E5%B0%94%E8%87%AA%E6%B2%BB%E5%8C%BA%E5%8E%BB%E6%9E%81%E7%AB%AF%E5%8C%96%E6%9D%A1%

E4%BE%8B/?lang=en [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018] came into force, helping give the veneer of legality to this new phase of “de-extremification” work. These regulations were the first in the nation to define “extremification” in the law, defining it in Article 3 as “being influenced by religious extremism, expressing views and engaging in behavior under the influence of extremism and exaggerated religious concepts which reject and interfere with normal production and life.” It lays out 14 manifestations of extremism such as “generalizing the concept of halal” and “irregular beards or name selection,” as well as the vaguely worded “other speech and acts of extremification.”

The regulations further require small leading groups on the issue to be formed in every government bureau at all levels from regional, prefectural and county levels and requires the creation of a system of leadership responsibility for the work and an annual target for appraising results. Article 14 calls for carrying out re-education work through “implementing a combination of individual and collective education, a combination of legal education and mentoring activities, a combination of thought education, psychological counseling, behavioral rectification and technical skills training, combining re-education and humane concern, strengthening the results of re-education.” All government departments and parts of society are called upon to include de-extremification in their work. Anyone who violates the regulations in a manner that doesn’t rise to the level of a crime will be corrected by public security and relevant departments, either by “criticism education” (批评教育) or legal education, or otherwise penalized through other relevant legislation such as the counter-terrorism law.

Despite this legislation, the current system of mass internment does not seem to have a basis in Chinese law. As Chinese legal scholar Jeremy Daum notes, the Counter-terrorism Law authorizes a maximum of 15 days detention for activities that do not rise to the level of a crime, and regarding the “education” provisions of the law, “there is no mention of detention in the discussion of corrective mentoring for minor offenses,” nor does the De-extremification Law mention detention in its education provisions.30Daum, J. (2018) XJ Education Centers Exist, but does their legal basis? [online] China Law Translate. Available at: https://www.chinalawtranslate.com/xj-education-centers-exist-but-does-their-legal-basis/?lang=en [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. He goes on to note that while the Counterterrorism Law does have an “educational placement” provision that appears to allow for indefinite detention, it is solely applied to those who have been convicted of and served a sentence for a terrorism charge. Because the internment camp system is detaining people who have not been convicted of a crime, available evidence suggests that the camps exist in an extralegal space.

The Scale and Nature of the Current Internment Camp System

After Party Secretary Chen Quanguo took office in 2016, the re-education campaign was expanded into the present system of internment camps. There appear to be a variety of terms used for the facilities. A 2016 work report glossary on the Lopnur County government website lists the term “three bases, one center: community rectification bases, legal education bases, placement bases for groups of special concern, and de-extremification re-education centers” ( 三基地一中心:社区矫正基地、法制教育基地、特殊群体安置帮教基地、“去极端化” 教育转化中心.)31尉犁政府网(2016). 2016年政府工作报告名词解释 [online] 尉犁政府网Available at: http://www.yuli.gov.cn/Item/75581.aspx [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. In 2016, Li Jianguo, secretary of the Bayingol Party Committee (李建国同 志巴州党委书记) visited the “center” in Lopnur, which was described as integrating all the “bases” into one “center,” which had by then re-educated 1,029 people.32尉犁零距離 (2016). 巴州黨委書記李建國到尉犁縣調研,都去哪了? 尉犁零距離 https://read01.com/AdQMO.html#.W0jJnNhKjOY [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. Meanwhile in Pichan County, Turpan Prefecture, the AB class three-tiered system continued, with 146 individuals in the “severe measures detention” A class (严打收押人员) and 116 individuals in the “relatively more poisoned” B level (中毒较深人员) re-educated at the prefecture level, with a further 21,884 B level individuals re-educated at the township and village level.33鄯善县“访惠聚”办公室 (2016) 凝心聚力 暖心富民 民族团结“十大工程”成效显著 –鄯善县民族团结进 步创建工作综述之六 [online] 鄯善县“访惠聚”办公室 Available at: http://www.xjssdj.com/ywkd/ywkdtb1/2016/1644503.htm [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018].

A paper published in 2017 by a professor at the Urumchi Party School calls for the creation of centralized facilities capable of holding at least 300 people.34邱媛媛(2017) 紧紧围绕总目标做好“去极端化”教育转化工作 [online] 和谐和会 Available at: http://www.doc88.com/p-2921386725182.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. It stated that it was a problem that the re-education work was being led by different departments and organized differently in separate locales, with a variety of names for the facilities. The different terms the paper mentions- “‘centralized transformation through education training centers’ (集中教育转化 培训中心), ‘legal system schools’ (法制学校), and ‘rehabilitation correction centers’ (康复矫治 中心)” appear in 73 government procurement documents analyzed by Adrian Zenz.35Zenz, A. (2018). “Thoroughly Reforming them Toward a Healthy Heart Attitude” China’s Political Re-Education Campaign in Xinjiang [online] Available at: https://www.academia.edu/36638456/Thoroughly_Reforming_them_Toward_a_Healthy_Heart_Attitude– _Chinas_Political_Re-Education_Campaign_in_Xinjiang [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018].

Zenz notes that most of the procurement notices for the construction of new facilities appeared in March 2017, right before the reported beginning of the expanded detainment campaign in April.36Ibid. The number and monetary value of the notices was highest in the months after the beginning of the construction push, falling later in 2017 through 2018. The first recruitment notices to staff them appeared in May 2017, advertising positions for teachers, as well as for police in the internment camps. The bids suggested both the construction of new facilities and the expansion of existing ones, with some being combined with vocational training facilities. Zenz notes the bids include high walls, fences, barbed wire, surveillance and access control systems as well as accommodations for armed guards, revealing the prison-like nature of these facilities.

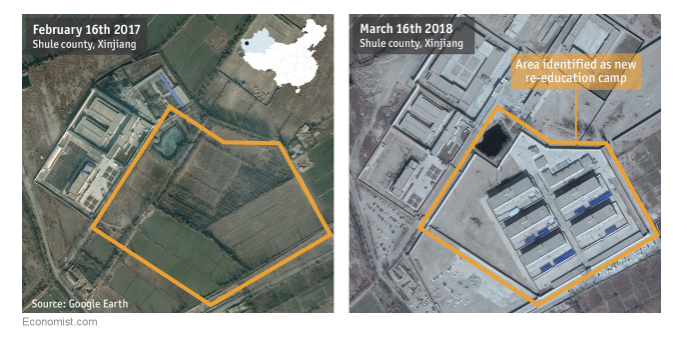

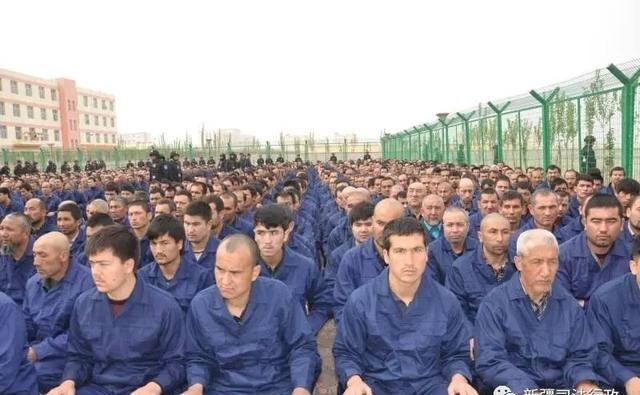

The scale of the transformation of the de-extremification campaign into a system of internment camps is enormous. A leaked official document published in Newsweek Japan stated that there were 890,000 Uyghurs interned in March of 2018.37水谷尚子(2018) ウイグル絶望収容所の収監者数は89万人以上 [online] Newsweek Japan Available at: https://www.newsweekjapan.jp/stories/world/2018/03/89-3_1.php [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. Adrian Zenz estimates that the number of interned could be over a million if regional and prefecture level cities are added to this number and if one assumes the anecdotal rate of 5 to 10% is true.38Zenz, A. (2018). “Thoroughly Reforming them Toward a Healthy Heart Attitude” China’s Political Re-Education Campaign in Xinjiang [online] Available at: https://www.academia.edu/36638456/Thoroughly_Reforming_them_Toward_a_Healthy_Heart_Attitude– _Chinas_Political_Re-Education_Campaign_in_Xinjiang [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. A limited number of photographs of the reeducation centers have appeared in media reports or social media. Utilizing the government bidding documents and other sources, Shawn Zhang has attempted to corroborate the existence of the facilities using Google earth satellite imaging, documenting the conversion of existing facilities and the construction of new ones.39Zhang, S. (2018). Where are the “Re-education camps”? [online] Medium Available at: https://medium.com/@shawnwzhang/where-are-the-re-education-camps-77f3084bc2c4 [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. In one example, he matched street level photo of a facility in Artush, topped with a sign declaring it to be a “neighborhood center,” to a satellite photo. It appears to be an unused factory complex now surrounded by high walls and guard towers.40Zhang. S. (2018). Satellite Imagery of Xinjiang “Re-education Camp” No. 23 新疆再教育集中营卫星图 23 [online] Medium Available at: https://medium.com/@shawnwzhang/satellite-imagery-of-xinjiang-re-education-camp-1- %E6%96%B0%E7%96%86%E5%86%8D%E6%95%99%E8%82%B2%E9%9B%86%E4%B8%AD%E8%90%A5%E5 %8D%AB%E6%98%9F%E5%9B%BE-1-eea378e8ed8b [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018].

Many of the internment camps are repurposed from other buildings. Radio Free Asia (RFA) has reported that officials and others who have traveled to the region state that various government buildings and schools were serving as internment camps,41Hoshur S. (2018). Uyghur Detentions Continue in Xinjiang, Despite Pledge to End With Party Congress [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at; https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/detentions-01082018164453.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. and overcrowding in the makeshift facilities meant that some people were being released to continue undergoing reeducation by local cadres in their home villages.42Sulaiman, E. (2017). China Runs Region-wide Re-education Camps in Xinjiang for Uyghurs And Other Muslims [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/training-camps09112017154343.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. In April 2018 a Uyghur businessman said that in the vicinity of Ghulja there were five repurposed facilities including a Party School and a factory which was formerly a police training facility, who also said that numerous people including cadres and teachers were being held in them.433 Hoshur, S. (2018). Uyghurs in XUAR’s Ghulja City Held in at Least Five ‘Political Re-Education Camps’ [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/ghulja-04242018132236.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. In January of 2018 a security official from Kashgar prefecture told RFA that there were approximately 120,000 Uyghurs being held in four internment camps in the area, one of which was a repurposed middle school.44Hoshur, S. (2018). Around 120,000 Uyghurs Detained for Political Re-Education in Xinjiang’s Kashgar Prefecture [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/detentions01222018171657.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018].

In September 2017, RFA reported that police officers said there were three camps in Aktu county,45Sulaiman, E. (2017). China Runs Region-wide Re-education Camps in Xinjiang for Uyghurs And Other Muslims [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/training-camps09112017154343.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. and in October of 2017, officials from villages outside Hotan had told RFA that their target was 40%, while another in Kashgar prefecture said that they had not been given a quota but had been ordered to “severely punish” 80% of those detained with prison, sending the rest to the camps.46Hoshur, S. (2017) Nearly Half of Uyghurs in Xinjiang’s Hogan Targeted for Re-Education Camps [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/camps-10092017164000.html [Accessed 22 Aug.

2018]. In March of 2018, an official from a village outside of Ghulja told RFA that they had been ordered to send 10% of the village’s 4,131 residents to internment camps.47Hoshur, S. (2018). Xinjiang Authorities Up Detentions in Uyghur Majority Areas of Ghulja City [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/detentions-03192018151252.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. In June 2018, an official from a town in Qaraqash county told RFA that over 10% of the town’s 32,000 residents were interned, with 1,721 in camps and 1,731 sent to prisons, while a police officer in a second village said that 40% had been sent to the camps, saying they had been given a target number.48Hoshur, S. (2018). One in 10 Uyghur Residents of Xinjiang Township Jailed or Detained in ‘Re-Education Camp’ [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/target-06292018132506.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018] One ethnic Kazakh cadre fled to Kazakhstan, and testified that she worked at a camp holding 2,500 Kazakhs, and knew of two other facilities of the same size in the area, with more in the region.49Rickelton, C. and Dooley, B. (2018). Video: ‘This person will simply disappear’: Chinese secretive ‘reeducation camps’ in spotlight at Kazakh trial [online] AFP. Available at: https://www.hongkongfp.com/2018/07/17/personwill-simply-disappear-chinese-secretive-reeducation-camps-spotlight-kazakh-trial/ [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. Before being required to teach in the camp, she had be the head of a kindergarten.50Synovitz, R. (2018) Official’s Testimony Sheds New Light On Chinese ‘Reeducation Camps’ For Muslims [online] Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Available at: https://www.rferl.org/a/kazakhstan-officials-testimony-chinesereeducation-camps-muslims/29396709.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018].

The bids analyzed by Adrian Zenz suggest that the vocational training campaign has been folded into the internment camps, with some facilities containing both, or supposed vocational schools also featuring security systems and guardrooms, as well as recruitment for hundreds of guards.51Zenz, A. (2018). “Thoroughly Reforming them Toward a Healthy Heart Attitude” China’s Political Re-Education Campaign in Xinjiang [online] Available at: https://www.academia.edu/36638456/Thoroughly_Reforming_them_Toward_a_Healthy_Heart_Attitude– _Chinas_Political_Re-Education_Campaign_in_Xinjiang [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. On a visit to a shopping mall in Hotan, reporters from Der Spiegel found it only a fifth occupied, with many shops having notices saying they were closed as a “security and stability measure.”52Zand, B. (2018) A Surveillance State Unlike Any the World Has Ever Seen [online] Spiegel Online Available at: http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/china-s-xinjiang-province-a-surveillance-state-unlike-any-the-world-hasever-seen-a-1220174.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. A passerby told them the stores’ occupants had been “sent to school,” a euphemism for being sent to the camps. However, a plainclothes policewoman who was following them told them that the “employees had been sent away for technical training.”

Recruitment notices for teachers in the vocational schools required only a middle school degree and in at least one case was only hiring Han Chinese. In January 2018, the city of Kashgar released a description of a vocational training program for “unemployed youths” and relatives of the “three types of people.”53叶城县人民政府办公室 (2018). 叶城县2018年职业技能教育培训工作实施方案 [online] Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20180611081717/http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:HdbV3TLtuQJ:www.xjyc.gov.cn/html/zbwj/2018-1-9/1819115576882896.html+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=ca [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. They were to be held for at least three months in centralized “closed military style” sites or dispersed village sites. In addition to military drills, vocational training and the Chinese language, lessons include the Spirit of the 19th Party Congress, Xi Jinping Thought for a New Era of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics, beneficial government policies, law, de-extremification, ethnic unity, and scientific and health knowledge through lectures to increase their “Five Identifications” (identification with the motherland, Chinese people, Chinese culture, Chinese Communist Party and socialism with Chinese characteristics)54崔榕 (2016). 五个认同”与民族地区意识形态安全 [online] 光明日报 Available at: http://theory.people.com.cn/n1/2016/1106/c40531-28838685.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018] in order to make them obey the law and feel gratitude.55叶城县人民政府办公室 (2018). 叶城县2018年职业技能教育培训工作实施方案 [online] Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20180611081717/http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:HdbV3TLtuQJ:www.xjyc.gov.cn/html/zbwj/2018-1-9/1819115576882896.html+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=ca [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018].

In addition, vocational schools are run by local Party Committees in rural areas “to prevent men from taking part in activities that affect social stability,” in the words of a police officer in Yarkand county.56Hoshur, S. (2018). Threat of Re-Education Camp Drives Uyghur Who Failed Anthem Recitation to Suicide [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/suicide-02052018165305.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018] These schools, like the internment camps, focus heavily on teaching Chinese. A Uyghur man who was attending an open vocational class in Yarkand reportedly committed suicide after being threatened with being sent to an internment camp for six months to five years for not being able to recite the national anthem and oath of allegiance to the Communist Party in Chinese.57Ibid.

© WSJ

The targets for internment appear much the same as those targeted earlier for deextremification training. In September of 2017, a local police officer told RFA reporters that five types of people were being targeted for internment- “people who throw away their mobile phone’s SIM card or did not use their mobile phone after registering it; former prisoners already released from prison; blacklisted people; ‘suspicious people’ who have some fundamental religious sentiment; and the people who have relatives abroad.”58Sulaiman, E. (2017). China Runs Region-wide Re-education Camps in Xinjiang for Uyghurs And Other Muslims Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/training-camps-09112017154343.html

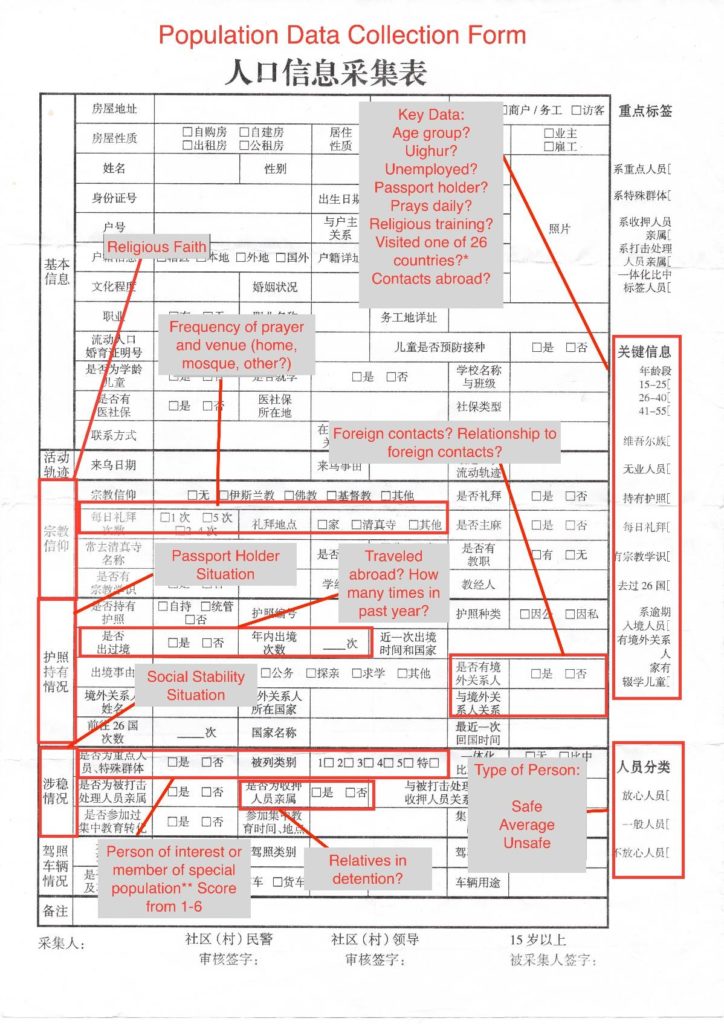

[Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. An official in Bayanday township in Ghulja County told RFA that anyone under forty years of age was being targeted as being from an “unreliable and untrustworthy generation.”59Hoshur, S. “Xinjiang Authorities Targeting Uyghurs Under 40 For Re-Education Camps” [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/1980-03222018155500.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. An official form collects information on Uyghurs, including whether they pray daily, have a passport, have relatives in detention, or are one of the “focus persons” or in a “group of special interest,” in order to determine their reliability, labeling them “safe, average or unsafe.”60Chin, J. and Burge, C. (2017). Twelve Days in Xinjiang: How China’s Surveillance State Overwhelms Daily Life [online] Wall Street Journal. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/twelve-days-in-xinjiang-how-chinassurveillance-state-overwhelms-daily-life-1513700355 [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018].

So-called “two-faced people,” that is to say Uyghurs, particularly cadres or religious personnel, suspected of being potentially disloyal are another target of the campaign. One Uyghur cadre, Pezilet Bekri, was reportedly sent to a re-education camp after being reported by her Han colleagues for sympathizing with Uyghurs detained in the camps, according to an anonymous source reported by RFA.61Hoshur, S. (2018). Uyghur Official Arrested For Sympathizing With Political ‘Re-Education Camp’ Detainees [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/arrested-04032018163824.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018].

The re-education program is spoken about by officials in terms creating immunity to disease. “Religious extremist thought” is described as a “malignant tumor” harming society.62艾尔西丁·阿木都拉 (2017). 遏制宗教极端思想渗透蔓延的法律武器 [online] 新疆日报 Available at: http://news.ts.cn/content/2017-04/20/content_12604391.htm [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. “De-extremification” helps create “immunity” to dangerous thought.63亚心网 (2014). 新疆奇台县:开展“去极端化”宣讲提升群众“免疫力”[online] 凤凰网Available at: http://news.ifeng.com/a/20141127/42585630_0.shtml[Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. The Aksu healthcare system even issued a list of “prescriptions” for treating “patients with ideological diseases.”64天山网 (2014). 新疆阿克苏妙用”十大处方””去极端化”综述之”[online] 天山网 Available at: http://news.ts.cn/content/2014-10/14/content_10601947.htm [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. These include intervening in their patient’s clothing choices or spiritual beliefs, unannounced inspections of local medical staff’s computers and cell phones, using scientific and Marxist thought to do a comparison check of one’s own thinking. The de-extremification campaign has not ended with the expansion of the camps. Through evidence gathered by dozens of interviews between July 2017 and June 2018, the Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD) estimates that in addition to 660,000 people being detained in camps in the southern region of East Turkestan, an additional 1.3 million may be being forced to attend re-education classes during the day or the evenings in “study sessions” or “open political camps.”65Xia, R., Clemens, V. and Eve, F. (2018) China: Massive Numbers of Uyghurs & Other Ethnic Minorities Forced into Re-education Programs [online] Chinese Human Rights Defenders. Available at: https://www.nchrd.org/2018/08/china-massive-numbers-of-uyghurs-other-ethnic-minorities-forced-into-reeducation-programs/ This constitutes 20-40% of many villages’ population.

The de-extremification campaign and its transformation into a massive system of indefinite detention in internment camps is aimed at curing the disease of “extremist thought.” Hotan Zero Distance published a tract stating that those sent to re-education were “sick in their thoughts,” having been “infected” with extremism, comparing religious extremism to a drug, cancer or a virus. Those “infected with terrorist thought” need to be sent to re-education to undergo “hospital treatment.” Thus, their detention is not punishment but rather intervention to ensure their entire family does not contract an “incurable disease.”66维汉双语 (2017). 到教育转化班学习是对思想上患病群众的一次免费住院治疗 [online] 和田零距离 Available at: https://read01.com/zh-cn/BL28Bk.html#.W05j49hKjOY [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. While speaking to RFA one official compared re-education to spraying chemicals on crops, saying “you can’t uproot all the weeds hidden among the crops in the field one by one.” While it is unclear how long the authorities expect this system of detention to last, it appears they expect it to be a permanent solution which will transform the Uyghur population.

Reaction to Internment Camps

The initial condemnation of the extrajudicial imprisonment of hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs was made by the human rights community and by many scholars specializing in the study or Uyghurs or of China. James Millward of Georgetown University published an editorial in the New York Times on the camps’ place within the police state the Chinese authorities have created.67Millward, J. (2018). What its Like to Live in a Surveillance State [online] New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/03/opinion/sunday/china-surveillance-state-uighurs.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. Rian Thum, an expert on the history of Uyghur religious practices, wrote “Xinjiang has become a police state to rival North Korea, with a formalized racism on the order of South African apartheid.”68Thum, R. (2018). What Really Happens in China’s ‘Re-education’ Camps [online] New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/15/opinion/china-re-education-camps.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. James Liebold of La Trobe University called on the Australian government to publicly condemn China’s behavior.69Liebold, J. (2018). Time to denounce China’ s Muslim gulag [online] the Interpreter. Available at: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/time-denounce-china-muslim-gulag [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. Scholar of the Chinese legal system Jerome Cohen called on relevant UN treaty bodies to review the situation and to press China to provide accurate information, and stated his support for the U.S. to implement Magnitsky Act sanctions.70Cohen, J. (2018) What can be done regarding Xinjiang’s mass detentions? [online] Jerry’s Blog. Available at: http://www.jeromecohen.net/jerrys-blog/2018/7/25/what-can-be-done-regardingxinjiangs-mass-detentions [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018].

Thus far governments have done little to directly address the situation, even if it is affecting their citizens. Kazakhstan has expressed concern in an official statement about treatment of Kazakhstani nationals and quietly intervened to have several released from the internment camps.71Pannier, B. (2018). Kazakhstan Confronts China Over Disappearances [online] RFERL Available at: https://www.rferl.org/a/qishloq-ovozi-kazakhstan-confronts-china-over-disappearances/29266456.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. The ethnic Kazakh Chinese official who described her work in the camps after fleeing to Kazakhstan was put on trail for crossing the border illegally, but was given a suspended sentence at the request of prosecutors and will not face deportation.72RFE/RL’s Kazakh Service (2018) Ethnic Kazakh Who Testified About ‘Reeducation Camps’ In China Will Not Be Deported [online] Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Available at: https://www.rferl.org/a/ethnic-kazakh whotestified-about-reeducation-camps-in-china-will-not-be-deported/29404925.html [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018].

Some of the first official condemnation of the camps has come from the United States. Kelley Currie, U.S. Ambassador to the Economic and Social Council of the U.N. cited the camps when she condemned the Chinese delegation once again blocking World Uyghur Congress president Dolkun Isa’s entrance to the U.N.73Worden, A. (2018). China Fails in its Gambit to Use the UN NGO Committee to Silence the Society for Threatened Peoples and Uyghur Activist DolkunIsa [online] China Change. Available at: https://chinachange.org/2018/07/10/china-fails-in-its-gambit-to-use-the-un-ngocommittee-to-silence-the-society-for-threatened-peoples-and-uyghur-activist-dolkun-isa/[Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. Senator Marco Rubio and Congressman Chris Smith, Chairs of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China called for Ambassador Terry Branstad to travel to East Turkestan and to prioritize the issue in meetings with Chinese officials.74Congressional-Executive Commission on China (2018). Chairs Urge Ambassador Branstad to Prioritize Mass Detention of Uyghurs, Including Family Members of Radio Free Asia Employees [online] CECC. Available at: https://www.cecc.gov/media-center/press-releases/chairs-urge-ambassador-branstad-to-prioritize-massdetention-of-uyghurs [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. At a Congressional-Executive Committee hearing on the issue in July 2018, the two legislators issued strong statements criticizing the silence of international institutions on the issue, and called on other nations’ governments to condemn the ongoing repression. Marco Rubio attacked private companies for “turning a blind eye to what’s happening” in order not to jeopardize their market access.75rubio.senate.gov (2018) Rubio Chairs China Commission Hearing on Xinjiang’s Human Rights Crisis [online] Marco Rubio U.S. Senator for Florida. Available at: https://www.rubio.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/pressreleases?id=58FEF0FD-A670-4587-A912-408A006A16D4 [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. In addition to calling for Magnitsky Act sanctions to be implemented, Congressman Chris Smith suggested the possibility of utilizing the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998 in the form of “broad economic sanctions targeting industries in Xinjiang that benefit China’s political leaders or other ‘state-owned entities.’”76Smith, C.(2018). Congressman Chris Smith, Co-chair Opening Statement: Suppression, Surveillance, and Mass Detention: Xinjiang’s Human Rights Crisis [online] Congressional-Executive Commission on China. Available at: https://www.cecc.gov/sites/chinacommission.house.gov/files/documents/hearings/Statement%20by%20Chris%20S mith_0.pdf [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. U.S. Ambassador at large for Religious Freedom Sam Brownback called for the use of Global Magnitsky Act sanctions on Chen Quanguo for his role in organizing the camps.77Paquette, D. (2018). Trump official seeks sanctions for Chinese leaders on human rights concerns [online] Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/trump-official-seeks-tosanction-chinese-leaders-on-human-rights-concerns/2018/06/28/e965c414-7a37-11e8-93cc6d3beccdd7a3_story.html?utm_term=.6257f3985201 [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018] However, there has been little reaction from international governments specifically addressing the issue of the internment camps.

The review of China’s implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination was the first instance of China responding to evidence of the existence of the camps, drawing international attention. Vice-chair of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination voiced the committee’s concerns about “the many numerous and credible reports that we have received that in the name of combating religious extremism and maintaining social stability (China) has changed the Uighur autonomous region into something that resembles a massive internment camp that is shrouded in secrecy, a sort of ‘no rights zone.’”

The response from the Chinese delegation was given by Hu Lianhe (胡联合), deputy chief of the United Front Work Department’s (UFWD) 9th Bureau covering Xinjiang affairs, although the UFWD was not listed among the participating Chinese ministries and institutions in a UN report on the meeting.78United Nations Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner (2018) Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination reviews the report of China [online] OHCHR. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=23452&LangID=E [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. He stated “[t]here are no such things as ‘re-education centers’ or ‘counter-extremism training centers’ in Xinjiang,” going on to say that authorities provide “criminals involved in only minor offences” with “assistance and education by assigning them to vocational education and employment training centers to acquire employment skills and legal knowledge, with a view towards assisting their rehabilitation and reintegration.”79Vanderklippe, N. (2018) China denies accusations of creating internment camps for Uyghurs [online] Globe and Mail. Available at: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/world/article-china-denies-accusations-of-creatinginternment-camps-for-uyghurs/ [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. In his response he used the term zaijiaoyuzhongxin(再教育中心 ), literally “re-education centers,” instead of terms such as “transformation through education centers” (教育转化中心), which are used in official tenders and other documents. Thus far Chinese officials are responding to criticisms of the mass internment policy by attempting to frame the network of internment camps as vocational training centers.

In the days after the CERD review, several articles appeared in Chinese media outlet the Global Times justifying the Chinese government’s repressive policies, stating “[p]eace and stability must come above all else. With this as the goal, all measures can be tried.”80Global Times (2018) Protecting peace, stability is top of human rights agenda for Xinjiang [online] Global Times Available at: http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1115022.shtml [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. This serves as a total justification of current policies as well as justifying any further escalation. A Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesman likewise blamed discussion of the camps at the CERD review on “certain anti-China forces” and foreign media making “distorted reports…out of ulterior motives.”81Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the People’s Republic of China (2018) Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Lu Kang’s Remarks [online] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the People’s Republic of China. Available at: http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/xwfw_665399/s2510_665401/t1585185.shtml [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. The Chinese government appears to be formulating a response to criticisms of international media reports. In a letter to the Financial Times in response to Emily Feng’s report entitled “Crackdown in Xinjiang: Where Have All the People Gone?,”82Feng, E. (2018) Crackdown in Xinjiang: Where Have All the People Gone? [online] Financial Times. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/ac0ffb2e-8b36-11e8-b18d-0181731a0340 [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018]. Chinese Ambassador to the U.K. Liu Xiaoming stated that the regional government’s “education and training measures” have been effective in preventing “the infiltration of religious extremism,” and that they include “employment training.”83Liu, X. (2018) Harmony in Xinjiang Based on Three Principles [online] Financial Times. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/05a81682-a219-11e8-85da-eeb7a9ce36e4 [Accessed 22 Aug. 2018] The letter also brought up Britain’s counterextremism initiatives, saying that “[e]very country needs to tackle this challenge effectively. It is time to stop blaming China for taking lawful and effective preventive measures.” The letter once again frames the camps as vocational training centers, and takes the additional step of comparing them to other nation’s counter-extremism initiatives.

III. Voices of the Camps

“Every Night I heard Crying”: Uyghurs Released From the Camps Speak Out

Interviewee One

Now living overseas, Interviewee One experienced conditions inside the internment camps and prior to his interview with UHRP spoke with AP journalist Gerry Shih.84Shih, G. (2018). Muslims forced to drink alcohol and eat pork in China’s ‘re-education’ camps, former inmate claims. [online] The Independent. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/china-re-educationmuslims-ramadan-xinjiang-eat-pork-alcohol-communist-xi-jinping-a8357966.html [Accessed 29 Jun. 2018].

Interviewee One came from a well-to-do family in Urumchi and graduated from Xinjiang University. He spent time in studying in Egypt and after his return to East Turkestan worked for the Xinjiang Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Following his position with the CCP, he was employed in the state media.

In April 2017, Interviewee One received a letter in Uyghur and then a call from neighborhood police officer called Shohret summoning him to an internment camp. When he questioned the officers as to the reason, he was told “every young Uyghur must go. If you don’t go, we’ll come and take you.”

By May 2017, Interviewee One was in a camp located near Ghulja. The internees were Uyghur and Kazakh and the facility held about 20,000 individuals. Internees consisted of women, men, children, young and old from a variety of professions; however, young Uyghurs were greater in number than any other group. Many of the young Uyghurs Interviewee One spoke to had connections overseas through study, travel or relatives.

Guards told him he was to teach Chinese to the internees due to the high proficiency in the language. Classes were held in small rooms and were two hours long with about 30 people in each group. The content of the classes included the writings of Confucius. Many of the students barely spoke Chinese and struggled with the classes. No Uyghur language was permitted in class.

Chinese authorities classified internees into three groups ranging from ‘good’ students to the ‘worst.’ Depending on classification an internee could expect different kinds of privileges. Interviewee One was considered among the group of safe internees and experienced the best treatment. His windowless room held 35 individuals. Others could expect up to 60 people in one room. There were no showers and usually one meal a day of poor quality. When asked what kind of food was served, Interviewee One said: “this food has no name.”

Internees woke up at 6 am when there would be a shift change in guards. From 6 am to noon, internees were contained in their rooms and expected to keep silent and look down at their feet. At noon, internees were served their daily meal. From 7 pm to 9 pm, the internees were expected to write self-criticisms. The content of the criticisms were admissions of ‘erroneous thinking’ and rejections of belief in Islam. Furthermore, internees were compelled to make pledges to consume alcohol, smoke tobacco, and tell other Uyghurs about the evils of Islam. Study of Chinese language and culture was to be praised in these written confessions. If internees did not or could not complete the daily self-criticism, guards beat them.

At night, Interviewee One described the only sounds in the camp were of people sobbing, dogs barking and guards shouting. He told UHRP: “Every night I heard crying.”

Interviewee One described conversations with a Uyghur businessman who was being pressured by guards to give them money to secure his release. After three weeks of internment, Interviewee One was released for three months due to an undisclosed family issue. Before he left the camp, he was secretly given a handwritten note from a Uyghur woman intended for her children. The note named each of her children and expressed how she missed them very much. She added the children must miss her very much too because it was the first time for them to be separated from each other. The note ended by saying it has been 84 days since she had seen them and that she didn’t know she would be staying away for so long.

With the help of relatives, Interviewee One fled to eastern China and then overseas. When he was in Shanghai he befriended a Uyghur, who told him he had received a police order to return to Urumchi. In concluding, Interviewee One said: “I’m sorry for all Uyghurs.”

“I am Here to Break the Silence”: Uyghurs With Relatives in Internment Camps

Halmurat Harri

Halmurat Harri is a Uyghur living in Finland. Both of his parents have disappeared into China’s internment camps. His mother was detained in April 2017 and his father in January 2018. Halmurat’s mother and father lived in the Xinqu (new district) of Turpan city, where they ran a store, prior to their disappearance. Before opening the store, his father worked as a UyghurChinese interpreter for the state and his mother as journalist. His parents are in their 60s. His father suffers from diabetes and needs treatment with insulin.

Halmurat told UHRP he has not been informed of his parents’ whereabouts despite repeated requests to local authorities in Turpan and he suspects they are being held in a facility in the city. Since October 2017, Halmurat has called government officials in Xinqu, including officers from the local police station, to inquire about the condition and location of his mother and father. Rather than offer any confirmation as to his parents’ welfare, local officials frequently insulted Halmurat for leaving China and called him a ‘terrorist.’ He was told he should come to China if he wanted to find out about his parents. Halmurat discovered his parents has been disappeared into an internment camp through calls to friends and neighbors. However, he said he has not been able to make these calls because no one will talk to him out of fear for themselves.

In his interview with UHRP Halmurat described a pattern of harassment from Chinese authorities due to his family history and overseas residency. He told UHRP his grandfather had fought for the second East Turkestan Republic against Nationalist Chinese armed forces and was subsequently persecuted during Cultural Revolution. Given this family history, Halmurat’s parents avoided political discussion and activism. Nevertheless, while still in East Turkestan, Halmurat was arbitrarily detained for 10 days in 2008 and his parents secured his release only after paying a 100,000 RMB bribe to police. In 2009, he settled in Finland and became a naturalized Finnish citizen in 2014. In 2015, he organized trips to Turkey and Dubai to meet his parents, who traveled to see him from East Turkestan. Traveling on his Finnish passport, Halmurat returned to East Turkestan in 2016 and early 2017 to visit his family. On both trips he was interrogated and threatened at the airport upon arrival and departure. Although he has received no indication as to why his parents have been disappeared into an internment camp, Halmurat believes it due to his family’s “rebellious history,” visits overseas, and his Finnish citizenship.

Halmurat’s grandmother passed away in February 2018 and his father was unable to attend the funeral because he had been taken into an internment camp a month earlier. When he learned of this, he decided to speak out about his parents’ disappearance. He said: “This is about being human. We want to be respected as humans. Is it too much to ask? I am here to break the silence.” More information on Halmurat’s case can be found on his blog (https://uyghurs.blog/).

Interviewee Three

Interviewee Three is a Uyghur from Ghulja and has lived overseas since 2017. His wife and daughter remain in China. His parents are detained in an internment camp. Chinese authorities took his mother in December 2017 and his father in December 2018. He learned about his parents’ detention from a close family friend.

In May 2018, Interviewee Three spoke to his mother through a third party using an undisclosed method. He believes the communication was possible because his mother speaks Chinese well and that this has given her small privileges inside the camp. However, his father is not fluent in Chinese and as a result he has afforded fewer privileges. Interviewee Three’s mother told him everything is OK and that she “is learning Chinese.” Interviewee Three expressed relief at hearing his mother’s voice but he is convinced she could not speak freely. His father-in-law is also in an internment camp and acts as Chinese instructor due to his high proficiency level. As an instructor he is permitted to make calls from the “instructor’s phone.”

Chinese authorities in Ghulja have not notified Interviewee Three about his parents’ detention and whereabouts. Nevertheless, he thinks they are in a facility located within a business development zone. According to Interviewee Three, through conversations with individuals who were once internees in the camps, conditions inside are severe. Internees are not allowed to wear shoelaces, belts and shirts with buttons to prevent suicide attempts. In addition, internees requiring medication cannot self-administer due to the possibility of intentional overdose. While he has no formal reason as to his parents’ detention, Interviewee Three believes it is because they had visited countries overseas.

Interviewee Four

Since the mid-2010s, Interviewee Four has been living in the United States. In East Turkestan, he was employed in manual labor in an undisclosed location. Interviewee Four and his parents owned land and a house, which local officials appropriated through intimidation. When he petitioned the government for a restoration of his property, Interviewee Four was arrested. Other Uyghurs in his village were also pressured to surrender their property. Through the help of close friends, he managed to secure paperwork to leave China. A new supermarket and holiday homes now occupy his land.

Interviewee Four’s brother is a successful businessman; however, in April 2018, his brother and his brother’s wife were disappeared into a internment camp Interviewee Four learned about the disappearance through a friend who had visited his village. He also discovered that his brother’s children are being cared for by his sisters.

In his interview with UHRP, Interviewee Four expressed his distress over the disappearance of his family members. The stress over hearing this news is compounded because he cannot speak to anyone in East Turkestan at the time of interview. Since the disappearance of his brother, his other family members have deleted him from their WeChat accounts. Interviewee Four added his brother and sister-in-law’s disappearance may be tied to his residence in the United States or because of the success his brother in business. He indicated that one year after his arrival in the United States, police in Urumchi questioned his brother.

In the light of his negative experience with local officials in East Turkestan regarding the appropriation of his land, Interviewee Four does not want to contact Chinese authorities to ask the whereabouts of his family members. He added: “There is no one who will listen.” The lack of information and recent accounts of poor conditions in the camps alarm him and he thinks his brother and sister-in-law might be susceptible to health problems.

Interviewee Five

Before fleeing to Europe in the mid-2010s, Interviewee Five was a businessman in East Turkestan. He left China after receiving a tip from a friend in the government that he was about to be arrested. Interviewee Five used money from selling his assets to bribe Chinese officials into issuing a passport and securing passage out of China. During his time in East Turkestan, he became involved in charitable causes. Interviewee Five said this, and his family’s ‘counterrevolutionary’ background, raised Chinese government suspicions about him. Charitable organizations he helped found were ordered to appoint government officials as directors. He told UHRP “eventually we were squeezed out.”

Since he fled, approximately 65 of Interviewee Five’s relatives have either been jailed or interned in camps. He said, “this has happened to them because of me.” Shortly after arriving overseas, Interviewee Five received a threatening phone call from regional police in East Turkestan. The police officer, a Uyghur, told him you must return to China or we will “harm your family.” The phone call was followed by a second from a Han Chinese police officer speaking Uyghur. The police officer warned him against disclosing any information about his family to the outside world. He told UHRP: “The government put pressure on me to go back to China and I didn’t go. Now, they are punishing my family.”

Among the family members either imprisoned or interned are four siblings, nephews, brothers-in-law, and relatives through marriage. Interviewee Five began to realize the scale of the retribution against him through Uyghurs traveling back and forth between East Turkestan and abroad. Later, he was able to get more information through WeChat contacts before those friends deleted his contact details from their profiles. Through these sources of information, he learned his relatives are being held in two locations, one in the south and one in the north of East Turkestan. One of his siblings was being held in a small room with about 30 people. Internees sleep head-to-toe due to the overcrowding. The food was described to him as “poor quality” consisting of a thin broth or bread. The internees are fed at most twice a day.

“He bashed his head against a wall to try to kill himself”: Testimonies of the camps in the international media

Alleged Crimes

The selection of internees for the internment camps appears limited to the Muslim population of East Turkestan, particularly Uyghurs, Kazakh, and Kyrgyz. The Chinese authorities have targeted broad categories of Muslims for detention into the camp system. An indication of the government’s focus of suspicion is seen in a crude system in assessing the ‘security risk’ of East Turkestan’s Muslim residents. A form circulated in the media detailed how everyone is designated ‘100 points,’ which are then docked if a person falls within certain categories. According to forms obtained from the Western Hebei Road Neighborhood Committee in Urumchi, the categories included: “Between Ages of 15 and 55; Ethnic Uyghur; Unemployed; Possesses Passport; Prays Daily; Possesses Religious Knowledge; Visited [one of] 26 [flagged] Countries; Belated Return to China; Has Association With Foreign Country; and Family With Children Who Are Homeschooled.”85Sulaiman, E. (2017). China Launches Racial Profiling Campaign to Assess Uyghurs’ Security Risk. [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/campaign-07142017165301.html [Accessed 13 Jun. 2018]. Each category is allocated ‘ten points’ and if a resident appears in enough categories to score below 50 points, they are labeled as ‘unsafe’ and candidates for political indoctrination.86A Der Spiegel article published in July 2018 indicates an alternative ‘points’ system in operation to assess the risk of Uyghur individuals.

A further indication of suspicious categories of Muslims came from a police officer who told Radio Free Asia (RFA) reporters persons of interest included “people who throw away their mobile phone’s SIM card or did not use their mobile phone after registering it; former prisoners already released from prison; blacklisted people; ‘suspicious people’ who have some fundamental religious sentiment; and the people who have relatives abroad.”87Sulaiman, E. (2017). China Runs Region-wide Re-education Camps in Xinjiang for Uyghurs And Other Muslims. [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/training-camps09112017154343.html [Accessed 13 Jun. 2018]. In March 2018, AFP reported how Pakistani’s with Uyghur wives and children in East Turkestan discovered their families had been interned in East Turkestan. See: https://www.hongkongfp.com/2018/03/26/pakistanis-distressed-uighur-wives-vanish-chinas-shadowy-networkreeducation-centres/ RFA confirmed the targeting of unemployed,88Hoshur, S. and Seytoff, A. (2018). Mandatory Indoctrination Classes For Unemployed Uyghurs in Xinjiang. [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/classes-02072018150017.html [Accessed 13 Jun. 2018]. young Uyghurs,89Hoshur, S. (2018). Xinjiang Authorities Targeting Uyghurs Under 40 For Re-Education Camps. [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/1980-03222018155500.html [Accessed 13 Jun. 2018]. and religious in two separate reports.90Long, Q. and Mudie, L. (2017). China Detains ‘More Than 100’ Uyghur Muslims Returning From Overseas Pilgrimage. [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/uyghur-pilgrims07042017164508.html [Accessed 30 Jun. 2018]. In addition, reports of elderly Uyghurs held in internment camps have circulated in the media, including the case of 82-year-old Ziyawudun Choruq, a former government official in Qara Yulghun.91Hoshur, S., Seytoff, A., Juma, M. and Lipes, J. (2017). Elderly Among Thousands of Uyghurs Held in Xinjiang Re-Education Camps. [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/elderly10262017150900.html [Accessed 30 Jun. 2018].

A special focus of Chinese authorities has been Uyghurs with overseas connections through either relatives resident abroad or travel overseas.92Radio Free Asia Uyghur Serivce (2018). Tikquduqtin tutulghan Uyghurlarning köp qismi “Tashliq say terbiyilesh merkizi” ge solan’ghan. [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/uyghur/xewerler/kishilikhoquq/terbiyilesh-merkizige-solanghan-uyghurlar-02012018221927.html?encoding=latin [Accessed 30 Jun. 2018] The Chinese authorities signaled their intention to punish Uyghurs overseas with the recall of their passports across China and denials to renew Uyghurs’ passports at Chinese Consulates abroad.93Hoja, G. (2017). China Expands Recall of Passports to Uyghurs Outside of Xinjiang. [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/passports-12082017152527.html [Accessed 13 Jun. 2018]. The pressure placed on Uyghurs regarding passports is a long-standing issue in China with problems documented since 2006; however, in the past, the measures were mostly contained within the region.94Uyghur Human Rights Project. (2013). Briefing: Refusals of passports to Uyghurs and confiscations of passports held by Uyghurs indicator of second-class status in China | Uyghur Human Rights Project. [online] Available at: https://uhrp.org/press-release/briefing-refusals-passports-uyghurs-and-confiscations-passports-held-uyghursindicator [Accessed 13 Jun. 2018]. Self-criticism of overseas experience is deemed an important aspect of the ‘reeducation’ process with some Uyghurs only released from camps if they express remorse over their travel abroad. Going abroad is often linked with ingratitude to the opportunities afforded Uyghurs under the CCP. The director of Public Security in Korla told RFA reporters the internees should admit “it was a mistake to travel abroad, when the [ruling Communist] Party and government have created such a high living standard in our own country.”95Hoshur, S. (2017). Uyghurs in Xinjiang Re-Education Camps Forced to Express Remorse Over Travel Abroad. [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/camps-10132017150431.html [Accessed 13 Jun. 2018]. In a further measure, authorities began to link the mere desire to go overseas with a reason for internment in a camp.96Hoshur, S. (2018). Xinjiang Authorities Detain Uyghurs ‘Wanting to Travel Abroad’. [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/travel-03272018162009.html [Accessed 13 Jun. 2018].