A joint report from the Uyghur Human Rights Project and the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs by Bradley Jardine and Lucille Greer. Read our press statement on the report here, and download the full report here.

I. Executive Summary

This report assesses China’s efforts to target Uyghurs in a region they once considered safe: the Arab world. China’s transnational repression of Uyghurs in this region has been growing in scale and scope as the country’s relations with Arab states have strengthened. According to our dataset, an upper estimate of 292 Uyghurs has been detained or deported from Arab states at China’s behest since 2001.

In a stunning example from July 2017, Egyptian police broke into apartments, scoured airports, and raided restaurants and mosques. They were not looking for Egyptian political dissidents but were hunting for Uyghurs on behalf of China’s Party-state. More than 200 Uyghurs, mostly students at Al-Azhar University in Cairo, were rounded up. At least 45 of them were rendered or deported to China; some of the 45 have not been heard from again. Interview data suggests that Chinese police were present in Egypt during interrogations, showing Beijing’s increasing willingness to intervene in the internal affairs of partner countries.

We have arrived at our upper estimate of 292 Uyghurs detained or deported from Arab states since 2001 in part through data from the China’s Transnational Repression of Uyghurs Dataset, a joint initiative by the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs and the Uyghur Human Rights Project. We have gathered and analyzed cases of China’s transnational repression of Uyghurs in Arab states using original interviews with Uyghurs who have fled the region, reports by experts and witnesses, and public sources in English and Arabic, including government documents, human rights reports, and reporting by credible news agencies. What follows is a comprehensive analysis of how China’s repression of Uyghurs has taken hold in Arab states and developed over the past twenty years. At least six Arab states—Egypt, Morocco, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE)—have participated in a campaign of transnational repression spearheaded by China that has reached 28 countries worldwide.

China’s Party-state uses five primary mechanisms of transnational repression to target Uyghurs in Arab states: 1) transnational digital surveillance, which enables them to track and closely monitor Uyghurs living outside their homeland; 2) Global War on Terror narratives, which serve as justification for the detention or rendering of Uyghurs to China; 3) institutions of Islamic education where Uyghur students enroll, which the Party-state targets for crackdowns; 4) the Hajj and Umrah in Saudi Arabia, which they use to surveil or detain Uyghur pilgrims (a trend accelerating with the increasing involvement of Chinese tech companies in Hajj digital services); and 5) denial of travel documents to Uyghurs in Arab states, rendering them stateless and vulnerable to deportation to the PRC.

To counteract China’s repression of Uyghurs in Arab states, we make a number of targeted policy recommendations to national, multilateral, and grassroots actors, including the following:

- Pass measures to protect Uyghur refugees. Governments should establish safe pathways for Uyghurs outside China to apply for resettlement without the need for UNHCR processing. For example, the U.S. Department of State should consider setting ambitious quotas for Uyghurs. Likewise, the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate should pass the complementary Uyghur Human Rights Protection Acts, which grant Priority 2 status for Uyghur and Turkic refugees.

- The international community must make new safe havens and resettle Uyghur refugees as traditional refuges for Uyghurs become scarce.

- Arab governments must utilize international support through Islamic organizations and multilateral organizations to approach the issue as a coalition and halt Chinese transnational repression in the region.

- University officials must intervene by using influence with their governments to find missing Uyghur students and graduates, and protect remaining Uyghur students from undue interference in their safety and education.

II. Introduction

Al-Azhar Mosque and University, one of the jewels of the Islamic world, has stood in Cairo for over a thousand years. It hosts the most prestigious program in Sunni Islamic studies as well as a thriving Arabic literature studies program. But in July 2017, the pride of Islamic education was struck by the heavy hand of China’s secularism. On July 1, in collaboration with the Chinese Party-state, Egyptian authorities rounded up Chinese nationals of Uyghur descent.1“Detained Uyghur Students Held by Egypt’s Intelligence Service,” Radio Free Asia, July 19, 2017, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/students-07192017124354.html More than 191 Turkic people from the Uyghur Region (also known as the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region)2Three terminological notes: 1) We refer to the government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as the “Party-state” or “Chinese Party-state” as a way of emphasizing one-party rule in China by the CCP and highlighting the difficulties in distinguishing between state and party apparatuses, policies, and actions. 2) We refer to the Uyghur homeland alternately as “East Turkistan” and the “Uyghur Region.” A vast majority of Uyghurs prefer these toponyms to those of “Xinjiang” and the “Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region,” which they see as offensive colonial terms. In cases where we refer to particular publications or government offices and apparatuses, however, we use “Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region” or related forms such as “XUAR” or “Xinjiang.” 3) We refer to the 22 members of the League of Arab States, which all speak a dialect of Arabic and have some shared Arab heritage, as Arab states. We use “states” specifically to highlight the agency of action on governments in this region that participate in transnational repression efforts against Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims. most of them studying at Al-Azhar University, were detained. We identified 65 individuals who were sent to China either via deportation or “voluntarily” after receiving ominous messages from both their relatives and Xinjiang Public Security Bureau officers. Chinese intelligence officers reportedly joined Egyptian security services in Cairo’s notorious Tora Prison to interrogate Uyghur students.3Also called the Scorpion Prison, Tora is the secretive fortress where political prisoners and enemies of the Egyptian state are sent and rarely released. For more, see Human Rights Watch, “We Are in Tombs: Abuses in Egypt’s Scorpion Prison,” September 28, 2016, https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/09/28/we-are-tombs/abuses-egypts-scorpion-prison According to a lawyer representing the students, many of them were physically assaulted, in addition to being denied food or water for extended periods.4Mohamed Mostafa and Mohamed Nagi, “‘They are Not Welcome Here’: Report on the Uyghur Crisis in Egypt,” Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression, October 1, 2017, https://afteegypt.org/en/academic_freedoms/2017/10/01/13468-afteegypt.html

For Uyghurs in their homeland, links to Arab states can be potentially fatal. In 2014, Communist Party General Secretary and President Xi Jinping called for a “People’s War on Terror” after a visit to the Uyghur Region in the wake of the Kunming Attack in Yunnan Province, an attack that no terrorist group claimed but state officials named as the work of Uyghur “separatists.”5“China Separatists Blamed for Kunming Knife Rampage,” BBC, March 2, 2014, www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-26404566

Chinese intelligence officers reportedly joined Egyptian security services in Cairo’s notorious Tora Prison to interrogate Uyghur students.

The same year, PRC military contractor China Electronic Technology Group began the process of building a large database of every Uyghur in the Uyghur Region, according to reports. The database would serve as a “preventative policing” program designed to predict one’s propensity for “terror.”6Sean Roberts, The War on the Uyghurs: China’s Internal Campaign against a Muslim Minority (Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press), 2020, 182. In essence, it was a project to profile millions of Uyghurs and inspect their communications and activities to determine their political loyalty to China. Since then, police officials have created and operated algorithmic blacklists of 26 primarily Muslim-majority countries deemed “suspicious.” Eight of the 26—Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Libya, Saudi Arabia, Syria, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Yemen—are Arab states.7Maya Wang, “China’s Algorithms of Repression: Reverse Engineering a Xinjiang Police Mass Surveillance App,” Human Rights Watch, May 1, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/ 05/01/chinas-algorithms-repression/reverse-engineering-xinjiang-police-mass8Maya Wang, “‘Eradicating Ideological Viruses’: China’s Campaign of Mass Repression in Xinjiang,” Human Rights Watch, September 9, 2018, https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/09/09/ eradicating-ideological-viruses/chinas-campaign-repression-against-xinjiangs# Uyghur students and businesspeople around the world have been recalled, arrested, imprisoned, and even killed on account of these blacklists.9“Two Uyghurs Returned From Egypt Dead in Chinese Police Custody,” Middle East Monitor, December 22, 2017, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20171222-2-uyghur-students-returned-from-egypt-dead-in-china-police-custody/

China’s transnational repression of Uyghurs has increased as the Party-state unleashed an unprecedented campaign of repression on Uyghurs back in their homeland. In a now-leaked internal speech from 2014, Xi Jinping also called for the state to utilize “the organs of dictatorship” to show “absolutely no mercy” in the “struggle against terrorism, infiltration, and separatism.”10Austin Ramzy and Chris Buckley “‘Absolutely No Mercy’: Leaked Files Expose How China Organized Mass Detention of Muslims,” New York Times, September 16, 2019, https://www.ny times.com/interactive/2019/11/16/world/asia/china-xinjiang-documents.html The results have been horror at an unprecedented scale accomplished by an all-powerful surveillance state. Since the beginning of the mass internment campaign in 2017, an estimated 1.8 million Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslim peoples have been arbitrarily rounded up in “re-education centers,”11Adrian Zenz, “China’s Own Documents Show Potentially Genocidal Forced Sterilization Plans in Xinjiang,” Foreign Policy, August 1, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/07/01/china-documents-uighur-genocidal-sterilization-xinjiang/ with millions more estimated to be incarcerated in the Chinese prison system or performing forced labor in factories around the PRC.12Vicky Xiuzhong Xu, Danielle Cave, James Leibold, Kelsey Munro and Nathan Ruser “Uyghurs for Sale,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, March 1, 2020, https://www.aspi.org.au/report/uyghurs-sale Reports of torture,13Rebecca Wright, Ivan Watson, Zahid Mahmood and Tom Booth, “’Some are just psychopaths’: Chinese detective in exile reveals extent of torture against Uyghurs,” CNN, October 5, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/04/china/xinjiang-detective-torture-intl-hnk-dst/index.html sexual assault,14Matthew Hill, David Campanale and Joel Gunter, “‘Their goal is to destroy everyone’: Uighur camp detainees allege systematic rape,” BBC News, February 2, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-55794071; see also Ivan Watson and Rebecca Wright, “Allegations of shackled students and gang rape inside China’s detention camps,” CNN, February 19, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/02/18/asia/china-xinjiang-teacher-abuse-allegations-intl-hnk-dst/index.html forced sterilization,15“China cuts Uighur births with IUDs, abortion, sterilization,” The Associated Press, June 29, 2020, https://apnews.com/article/ap-top-news-international-news-weekend-reads-china-health-269b3de1af34e17c1941a514f78d764c forced abortion,16Ayse Wieting, “Uighur exiles describe forced abortions, torture in Xinjiang,” The Associated Press, June 3, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/only-on-ap-middle-east-europe-government-and-politics-76acafd6547fb7cc9ef03c0dd0156eab family separation,17Adrian Zenz, “Break Their Roots: Evidence for China’s Parent-Child Separation Campaign in Xinjiang,” Journal of Political Risk, 7, no. 7, (July 2019), https://www.jpolrisk.com/break-their-roots-evidence-for-chinas-parent-child-separation-campaign-in-xinjiang/ and mass surveillance have revealed that the scope of this campaign is totalizing.18Human Rights Watch, “Break Their Lineage, Break Their Roots,” April 19, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/04/19/break-their-lineage-break-their-roots/chinas-crimes-against-humanity-targeting

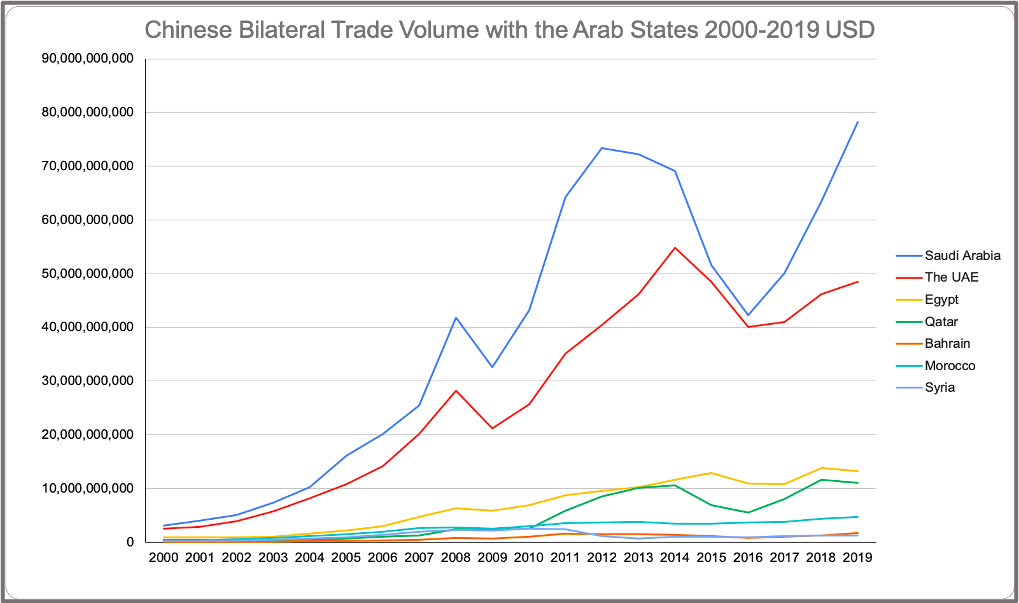

The PRC enhanced its relations with Arab states even as it mounted its interment offensive. What began with oil purchases in the 1990s has now blossomed into robust cooperation in trade, investment, politics, and security.19“China is Largest Foreign Investor in the Middle East,” Middle East Monitor, July 24, 2017, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20170724-china-is-largest-foreign-investor-in-middle-east/; World Integrated Trade Solution, “Trade Summary for Middle East & North Africa 2019,” https://wits.worldbank.org/countrysnapshot/en/MEA Through the support or tacit endorsement of Arab governments, China has added some of the strongest voices in the Islamic world to its defense. In 2019, major Arab powers including Saudi Arabia and the UAE were among the 36 countries that signed a letter at the UN endorsing China’s policies in the Uyghur Region.20“Saudi Arabia Defends Letter Backing China’s Xinjiang Policy,” Reuters, July 18, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-rights-saudi/saudi-arabia-defends-letter-backing-chinas-xinjiang-policy-idUSKCN1UD36J During a meeting in Beijing with General Secretary Xi Jinping in 2019, Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Muhammed bin Salman signaled support for the mass internment campaign when he said, “We respect and support China’s right to take counter-terrorism and de-extremism measures to safeguard national security.”21“Chinese President Meets Saudi Crown Prince,” Xinhuanet, February 22, 2019, http://www.xin huanet.com/english/2019-02/22/c_137843268.htm Furthermore, at least six Arab governments—Egypt, Morocco, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and the UAE—and their security services have cooperated in China’s campaign of transnational repression targeting the global Uyghur population through intimidation, detentions, and renditions back to China, the last of which have virtually guarantee immediate detention in a concentration camp.

At least six Arab governments—Egypt, Morocco, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and the UAE—and their security services have cooperated in China’s campaign of transnational repression.

Drawing from original interviews with witnesses and experts, along with analyses of Arabic-language source materials, this report aims to provide a comprehensive account of China’s transnational repression in Arab states today. We provide the first verified upper estimates of detentions and deportations of Uyghurs from Arab states, utilizing original interview data alongside the transnational repression database created by the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs (Oxus Society) and Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP). We also draw from primary and secondary-source materials to categorize and describe the mechanisms of transnational repression China utilizes most widely in Arab states. Finally, we chart the evolution of these states’ collaboration with China in transnational repression from the start of the Global War on Terror to the present day. This report shifts the discussion of Arab states’ regional role in China’s repression of Uyghurs from silence to complicity in an increasingly global “People’s War on Terror.”22The phrase “People’s War on Terror” is reproduced here critically. Then-XUAR Party Secretary Zhang Chunxian coined the phrase in 2014, deliberately invoking the United States’ far-reaching “War on Terror” while inaugurating the “Strike Hard Campaign Against Violent Extremism.” As discussed in greater detail within this report, the Chinese Party-state frames expression of religious identity as Islamic extremism, but this construction has a tenuous basis in reality.

III. Methods and Findings

This report utilizes the China’s Transnational Repression of the Uyghurs Database, a research tool built by the Oxus Society in partnership with UHRP to monitor global cases of Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples who have been targets of PRC-led transnational repression beyond China’s borders. The China’s Transnational Repression of the Uyghurs Database includes 336 fully verified cases of detentions or renditions of Uyghurs living overseas, with an upper total of 1,576 cases that lack complete biographical records of the individuals involved.

We have verified a total of 109 cases in Egypt, Morocco, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and the UAE with an upper estimate of 292 since 2004. We have based this upper estimate on findings from the China’s Transnational Repression of the Uyghurs Database, if we include bulk cases with limited details of particular individuals, or where individuals were reported with pseudonyms or anonymously. These figures rely on reported data, representing just the tip of the iceberg in terms of the number of renditions that are likely occurring according to anonymous interviews conducted by human rights organizations active in the region.

| Upper estimate of cases of stage 2 and stage 3 transnational repression in Arab states since 2001 | |

| Egypt | 274 (90 identified by Oxus and UHRP) |

| Morocco | 1 |

| Qatar | 1 |

| Saudi Arabia | 8 |

| Syria | 1 |

| UAE | 7 |

In compiling the China’s Transnational Repression of Uyghurs Database, of which these figures are a part, we have relied on public reporting by investigative journalists in the Middle East and North Africa. Some cases received high-profile coverage by virtue of their personal connections. One example is the case of Amina Allahberdi, a Uyghur resident of Saudi Arabia and PRC citizen who vanished after visiting China in 2016 after Saudi authorities requested she go there to renew her passport. Her disappearance received attention after her husband Sait bin ‘Abood al-Shahrani, a Saudi citizen and father of two children with Ms. Amine, made appeals on Saudi social media, as well as in international media.23“Interview: ‘It Hurts My Heart to See my Children Cry for Their Mother,’” Radio Free Asia, October 14, 2018, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/appeal-09142018145824.html This and other cases of transnational repression discussed in public reporting likely represent just a small fraction of the total renditions and detentions that have occurred in secret.

Amina Allahberdi, a Uyghur resident of Saudi Arabia and PRC citizen […] vanished after visiting China in 2016 after Saudi authorities requested she go there to renew her passport.

This report also references a number of secondary sources in English, Chinese, and Arabic, including online interviews and personal accounts by Uyghurs undergoing forms of transnational repression, as well as writing in traditional print, digital, broadcast, social media, and government documents. We have used these secondary sources to build a detailed overview of China’s transnational campaign to repress the Uyghurs, as well as to evaluate the accuracy of events recounted to us in interviews.

We have supplemented secondary sources with key informant interviews (KII) conducted with prominent activists such as Mohamed Soltan and Sara Gabr. We have also received confidential information from a third KII who requested anonymity. We complemented the KIIs with three Arabic-language interviews with Uyghur refugees in Arab states. These interviewees requested anonymity due to fear of threats on their lives. We selected interviewees based on their expertise in repression in Arab states, professional involvement in key events, and knowledge of China’s international policies. These KII interviews provided us with on-the-ground information about and eyewitness accounts of transnational repression in target countries. They also informed us about the larger civil society context in which the repression occurred.

IV. Mechanisms of China’s Transnational Repression

Transnational repression of Uyghurs around the world has worsened significantly in recent years. In a 2021 report on transnational repression titled “No Space Left to Run,” Oxus and UHRPdocumented 1,546 cases of stage 2 (arrests and detentions) and stage 3 (refoulements) transnational repression from 1997 to March 2021, demonstrating the growing scale of China’s campaign to target Uyghurs abroad.24Bradley Jardine, Edward Lemon, and Natalie Hall, “No Space Left to Run,” Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs and Uyghur Human Rights Project, June 24, 2021, https://uhrp.org /report/no-space-left-to-run-chinas-transnational-repression-of-uyghurs/ Other organizations have documented this trend as well. From September 2018 to September 2019, Amnesty International interviewed 400 Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Uzbeks, and other Turkic peoples from China living in 22 countries across five continents to assess the degree of targeted repression they have experienced.25Nowhere Feels Safe,” Amnesty International, February 2020, https://www.amnesty.org /en/latest/research/2020/02/china-uyghurs-abroad-living-in-fear/ Safeguard Defenders, an NGO that promotes rule of law, noted China dramatically increased the number of Red Notices submitted through Interpol since 2014 to pursue citizens abroad, including Uyghurs.26Safeguard Defenders, “No Room to Run: China’s expanded mis(use) of INTERPOL since the rise of Xi Jinping,” November 15, 2021,https://safeguarddefenders.com/en/blog/chinas-use-interpol-exposed-new-report, 13-14.

The Chinese Party-state uses five primary mechanisms of transnational repression to target Uyghurs in Arab states: 1) transnational digital surveillance, which enables them to track and closely monitor Uyghurs living outside their homeland; 2) Global War on Terror narratives, which serve as justification for the detention or rendering of Uyghurs to China; 3) institutions of Islamic education where Uyghur students enroll, which the Party-state targets for crackdowns; 4) the Hajj and Umrah in Saudi Arabia, which they use to surveil or detain Uyghur pilgrims (a trend accelerating with the increasing involvement of Chinese tech companies in Hajj digital services); and 5) denial of travel documents to Uyghurs in Arab states, rendering them stateless and vulnerable to deportation to the PRC.

Transnational Digital Surveillance

China conducts transnational repression of Uyghurs in Arab states in 2021 by internationalizing algorithmic surveillance systems used in the Uyghur Region—namely the Integrated Joint Operating Platform (IJOP). These systems mine personal data from residents in the Uyghur Region and produce verdicts on whether individuals are “trustworthy” to the Chinese Communist Party. Any connection to an individual in a blacklisted country is grounds for detention and “re-education.” Simply living in these countries may result in immediate detention after crossing the border into PRC territory, as outlined in a CCP document leaked with the “China Cables” in 2019.27“Integrated Joint Operating Platform Daily Essentials Bulletin No.2,” International Consortium of Investigative Journalists,” November 24, 2019, https://www.icij.org/investigations/china-cables/read-the-china-cables-documents/; and Maya Wang “China: Big Data Fuels Crackdown in Minority Region,” Human Rights Watch, February 26, 2018, https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/02/26/china-big-data-fuels-crackdown-minority-region#. Since 2017, Party-state officials have called for Uyghurs in Arab states to return home, denying them the appropriate paperwork to travel anywhere other than the PRC. In some cases, the authorities have orchestrated arrests with Arab security services.

A trove of documents leaked in November 2019, known as the “China Cables,” gives observers a glimpse into the state-sanctioned use of technology to target Uyghurs abroad. Some of the leaked cables revealed that police received explicit directives to arrest Uyghurs with dual citizenship and to track XUAR residents living abroad—some of whom were later deported back to China and arrested. The database categorizes people as “suspicious” for any contact with 26 blacklisted countries, including Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Libya, Saudi Arabia, Syria, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Yemen.28“‘Eradicating Ideological Viruses’: China’s Campaign of Mass Repression in Xinjiang,” Human Rights Watch, September 9, 2018, https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/09/09/eradicating-ideological-viruses/chinas-campaign-repression-against-xinjiangs# Individuals who have been to these countries, have family in these countries, or communicate with people there have been detained, interrogated, and even convicted and imprisoned, usually on charges of “extremism.” According to our data, seven Uyghurs have been detained in Qatar, Morocco, and the UAE—all of which appear in IJOP country blacklists—since 2017. The UAE’s close relationship with Beijing through a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership is of particular concern for Uyghurs in the region because many fear deportation.

For those still outside the country for whom suspected terrorism cannot be ruled out, the border control reading will be carried out by hand to ensure that they are arrested the moment they cross the border.

China’s embassies and consulates play a key role in the use of technology as a mechanism for transnational repression. In the leaked document “Bulletin No. 2”, 1,535 people originally from the Uyghur Region were flagged as foreign nationals who had applied for a Chinese visa. Among those, 637 had returned to visit the Uyghur Region since June 1, 2016. The directive stated that all individuals on the lists were to be monitored and inspected one by one and that those who had already canceled their Chinese citizenship and were suspected of terrorism should be deported from the PRC back to their country of origin.29“Integrated Joint Operating Platform Daily Essentials Bulletin No.2,” International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, November 24, 2019, https://www.icij.org /investigations/china-cables/read-the-china-cables-documents/ The directive added that those who were suspected of terrorism but still retain Chinese citizenship should be sent to reeducation camps. It also noted that 4,341 other XUAR residents had received valid travel documents abroad from Chinese embassies and consulates to study in countries such as Egypt.30Ibid.

According to information revealed in the China Cables, students returning from overseas risk being arrested on the spot:

For those still outside the country for whom suspected terrorism cannot be ruled out, the border control reading will be carried out by hand to ensure that they are arrested the moment they cross the border.31Ibid.

This policy was in place in 2017 when XUAR security officials sent out calls for Uyghurs living abroad to return in order to “register” themselves.32Jessica Bake “China is Forcing Uyghurs Abroad to Return Home. Why Aren’t More Countries Refusing to Help?” ChinaFile, August 14, 2017, https://www.chinafile.com/reporting-opinion/viewpoint/china-forcing-uighurs-abroad-return-home-why-arent-more-countries It was the fate that met Uyghur students Abdusalam Mamat and Yasinjan, who had studied at Al-Azhar since 2015. They volunteered to return to the Uyghur Region after receiving an order to do so in 2017. Both were arrested on their arrival and later died in Chinese police custody, despite having no underlying illnesses that would have contributed to their deaths.33“2 Uyghur Students Returned from China, Dead in Chinese Police Custody,” Middle East Monitor, December 22, 2017, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20171222-2-uyghur-students-returned-from-egypt-dead-in-china-police-custody/

An entire government database that targets Uyghurs also leaked recently, providing further insight. In March 2021, the Shanghai Public Security Bureau (PSB), a police force that engages in intelligence gathering, was hacked and 1.1 million surveillance records were leaked. One of the revelations from this trove of documents was that an unprotected database with the codename “Uyghur Terrorist,” was part of an open-source database accessible by security agencies around the world. The presence of this platform is just a small glimpse into the enormous scope of China’s international campaign against Uyghurs.34“Australians Flagged in Shanghai Security Files Which Shed Light on China’s Surveillance State and Monitoring of Uyghurs,” ABC (Australia), April 1, 2021, https://www.abc.net. au/news/2021-04-01/shanghai-files-shed-light-on-china-surveillance-state/100040896 More than 400 individuals in the database flagged for in-person examination were minors, some of whom were as young as five years old.35Shockingly, the database also included information on more than 5,000 foreigners flagged for further monitoring simply because they traveled to Shanghai. “Australians Flagged in Shanghai Security Files Which Shed Light on China’s Surveillance State and Monitoring of Uyghurs,” ABC (Australia), April 1, 2021, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-04-01/shanghai-files-shed-light-on-china-surveillance-state/100040896

Participation in Islamic education is also evaluated by the CCP’s algorithms. Islamic education institutions in Arab states, previously a draw for Uyghurs due to their prestige and generous scholarship funding, are particularly vulnerable to algorithmic targeting. In today’s surveillance climate, studying Islam and residing in a blacklisted country virtually guarantees detention in camps. The 2017 crackdown on Al-Azhar students is the most well-known example, but similar crackdowns also occurred at least at the Islamic University of Madinah in Saudi Arabia. An anonymous interviewee told us that 10 students and graduates of that university have vanished into the PRC system of re-education centers, likely due to the Islamic nature of their studies. We were able to independently verify one of these students. PRC repression may extend to other Islamic education institutions in Arab states as well. In 2021, Uyghur students at Islamic universities in these countries are in very real danger of being detained and potentially deported to the PRC.

The Hajj and Umrah in Saudi Arabia have become snares to collect Uyghurs as they conduct pilgrimages. Since 2018, four Uyghurs have been seized and forcibly repatriated to China while they performed religious duties in Mecca and Medina. Additionally, Chinese tech companies like Huawei are becoming involved in Hajj digital services, opening the door for surveillance technology to play a role in Saudi Arabia as it has in the Uyghur Region. Undertaking Hajj and Umrah in 2021 can be dangerous for Uyghurs even if they have legal permanent residency in third countries.

The agents reportedly handed him a USB and instructed him to insert it into his ex-wife’s computer to infect it with spyware. The MSS reportedly offered him cash, a room in the Hilton, and toys for his children.

Reporting from August 2021 suggests the UAE may be functioning as a regional intelligence hub for Chinese intelligence and security services. In 2019 Norway-based Uyghur activist Abduweli Ayup spoke with three Uyghurs in Turkey who had been forced to spy on the diaspora there for China’s government. The men said they flew to Dubai to collect burner phones and payment from Chinese intelligence officers stationed in the UAE.36“Detainee Says China has Secret Prison in Dubai, Holds Uyghurs,” Associated Press, August 16, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/china-dubai-uyghurs-60d049c387b99b1238ebd5f1d3bb3330 The men’s claims match other claims made in August 2021 by Jasur Abibula, a Netherlands-based Uyghur and former husband of Asiye Abdulahed. Ms. Asiye rose to prominence for leaking the “China Cables” about the mass incarceration program in the Uyghur Region to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.37Ibid. Mr. Jasur said he was lured to Dubai where he met with two MSS officers. The agents reportedly handed him a USB and instructed him to insert it into his ex-wife’s computer to infect it with spyware. The MSS reportedly offered him cash, a room in the Hilton, and toys for his children.38Ibid. According to Mr. Jasur, the officers were prone to using sticks as well as carrots in their recruitment efforts. During a drive past the sand dunes outside Dubai, one of the men informed him: “If we kill and bury you here, nobody will ever be able to find your body.”39Ibid. Mr. Jasur, now in the Netherlands, showed international media photos of the agents, along with his hotel and plane tickets to support his allegations. The same Associated Press report also suggested the Chinese Party-state may be operating black site detention facilities in Dubai, but was unable to verify these claims.40“Detainee Says China has Secret Prison in Dubai, Holds Uyghurs,” Associated Press, August 16, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/china-dubai-uyghurs-60d049c387b99b1238ebd5f1d3bb3330 We have also been unable to verify these claims; over the course of writing this report, we did not encounter any similar claims except in a confidential 2021 ICC court filing which suggested a black site detention facility may be operated by China from Dushanbe Airport in Tajikistan.

Global War on Terror Narratives

When the United States declared its Global War on Terror (GWOT) in 2001, China ushered in a new phase of its decades-long campaign against the Uyghurs by capitalizing on the heightened security environment to pursue refugees, falsely labeling them as “terrorists.” In exchange for Chinese support of its invasion of Iraq, the U.S. government designated the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) as a terrorist organization in 2002 as a quid pro quo.41“U.S. Removes Group Condemned by China From ‘Terror’ List,” Al Jazeera, November 7, 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/11/7/us-removes-group-condemned-by-china-from-terror-list By labeling ETIM as a terrorist organization, the Party-state could arbitrarily declare nearly any Uyghur group or individual to be members or associates of ETIM and therefore terrorists, which made the U.S designation a potent aid in—and arguably a model for—persecution in the Uyghur Region.

With the GWOT underway, prominent Uyghur cultural figures worldwide found themselves facing ever greater scrutiny. One such figure was Ahmatjan Osman in Syria, a Uyghur poet known across Arab states for his classical verse. Mr. Ahmatjan has argued that Chinese authorities put pressure on Syria in 2004 to deport him out of fear that his poetry would unite Uyghur nationalists abroad.42“Ahmatjan Osman Speaks to Haleh Salah on His Experience as a Student in Syria [أحمد جان عثمان متحدثاً ل هالة صالح عن تجربته كطالب في سوريا],”BBC Arabic, July 10, 2017, https://www.bbc.com/arabic/tv-and-radio-40557722; “Syria President al-Assad visits China,” China Daily, June 22, 2004. Ahmatjan had to apply to the United Nations for refugee status after being expelled from Syria despite having lived there for 15 years, being married to a Syrian national, and having two children born in that country. When the news emerged that Syrian authorities had expelled Ahmatjan, 270 prominent figures in the world of Arabic poetry, including the Syrian poet and Nobel Literature Prize nominee Adunis, signed a petition and staged a protest against the deportation order.43“Ahmatjan Osman Speaks to Haleh Salah on His Experience as a Student in Syria [أحمد جان عثمان متحدثاً ل هالة صالح عن تجربته كطالب في سوريا],”BBC Arabic, July 10, 2017, https://www.bbc.com/arabic/tv-and-radio-40557722 He was granted Canadian citizenship in October 2004 and has been living in Canada since.

Uyghurs fell victim to GWOT narratives in the Gulf in 2008. That year, Uyghur men named Abdelsalam Abdallah Salim (a resident of al-Ain) and Akbar Omar (a resident of Dubai) were imprisoned in the UAE in connection with an alleged plot to blow up the dragon statue in front of Dubai’s Dragon Mart during the Summer Olympics in Beijing.44Hassan Hassan, “Uighur terrorists jailed for DragonMart bomb plot,” The National UAE, July 1, 2010, https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/courts/uighur-terrorists-jailed-for-dragonmart-bomb-plot-1.583748? After two years in solitary confinement in al-Wathba Prison in Abu Dhabi, the men were sentenced to a further 10 years imprisonment in June 2010, reportedly without any judicial proceedings or legal support, a violation of their rights under the UAE’s Code of Criminal Procedures.45“الامرات العربية المتحدة: فريق العمل يؤكد الطابع التعسفي للاحتجاز مواطنين من الويغور [United Arab Emirates: Task Force Confirms the Arbitrary Nature of the Detention of Uyghur Citizens],” Alkarama, November 20, 2011, https://www.alkarama.org/ar/articles/alamarat-alrbyt-almthdt-fryq-alml-ywkd-altab-altsfy-llahtjaz-mwatnyn-mn-alwyghwr Human rights observers speculated that they would be deported to China to serve their sentence there. The details of their case provide room for doubt over the validity of the charges against them. One report at the time indicated that the Chinese Embassy notified local authorities about the two men, whose names have been obscured in English-language coverage to the Sinicized variants Mayma Ytiming Shalmo and Wimiyar Ging Kimili respectively.46“Two Chinese Uyghurs Jailed for Failed UAE Bomb Plot – Paper,” Reuters, July 1, 2010, https://www.reuters.com/article/instant-article/idUSLDE66004X Furthermore, the men’s initial confessions had been coerced “through fear,” and the translators—from Uyghur to Mandarin and then into Arabic—were provided by China, which also sent translators and representatives to attend the hearings.

[T]he men’s initial confessions had been coerced “through fear,” and the translators—from Uyghur to Mandarin and then into Arabic—were provided by China.

Their case was referred to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Working Group on Arbitrary Detentions in 2011. The Working Group released its opinion the following February as A/HRC/WGAD/2011/34. When the Working Group contacted the Emirati government for a response, the UAE did not deny the delayed trial, use of torture, confessions obtained under the threat of rendition to China and the death penalty, and the absence of legal proceedings and support. The UN stated it “deplores that the [UAE] Government has not provided it with the necessary elements to rebut these allegations.” On the question of expulsion to China after their sentencing, the official response from the UAE was that “the Government considers that it will be undertaken pursuant to the treaty between the two countries that includes a provision allowing them to serve their sentence in their own country.” Based on the evidence presented, the Working Group ruled the detention of the two men in the UAE as arbitrary.47“Opinions Adopted by the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention at its sixty-first session, 29 August – 2 September 2011 – No. 34/2011 (United Arab Emirates),” United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, February 28, 2012, https://ap.ohchr.org/documents /dpage_e.aspx? We could not independently verify whether they were rendered to China, but given the official response of the UAE government and China’s own policies, this outcome seems likely. There has been no information about the two men since their sentencing in 2010.

The recent case of Idris Hasan (also known as Aishan Yideresi), who was detained in Morocco in July 2021, highlights China’s use of overlapping mechanisms such as international organizations like Interpol and bilateral extradition treaties to pursue Uyghurs. Mr. Idris, a computer engineer, worked as a translator for a Uyghur diaspora news outlet in Turkey documenting China’s repression in the Uyghur Region. As he began to fear for his safety following several detentions by Turkish authorities, he chose to flee to Morocco, but was detained on July 19 in Casablanca Airport and sent to a prison near Tiflet.48Ehsan Azigh, “Moroccan Court Rules in China’s Favor to Extradite Uyghur Accused on ‘Terrorism,’” Radio Free Asia, December 16, 2021, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur /idris-hasan-12162021175312.html Representatives of the Chinese Party-state issued an Interpol Red Notice for his capture, alleging Mr. Idris was a “member of ETIM.”49Ibid. This accusation was found to be without evidence and Interpol suspended the Red Notice on August 2021, citing its bylaws forbidding persecution on political, religious, or ethnic grounds.50Ibid. Moroccan courts proceeded to try Mr. Idris however, referencing its own extradition treaty with China from 2016—part of a strategic partnership between the two countries that included economic and financial investments.51Ibid. Mr. Idris has been unable to speak with his wife and three children since his detention. On December 16, 2021, the Court of Cassation in Morocco ordered his extradition.52Ibid.

Institutions of Islamic Education

Islamic education has also become a mechanism for China’s transnational repression of Uyghurs in Arab states. Following the harsh suppression of Islam during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), the PRC began to support the recovery of Islam in China in the 1980s. The Party-state established ten Islamic education colleges throughout China, including in Ürümchi, and provided tuition and stipends to students to pursue formal training as imams. This granted the authorities a high level of control over Islamic instruction with the power of selection for teachers and students. As the government walked back funding for students at domestic Islamic colleges in the late-1980s, scholarships from other countries compelled Uyghur and other Muslim students to pursue Islamic studies abroad.53Jackie Armijo, “Islamic Education in China: Rebuilding Communities and Expanding Local and International Networks,” Harvard Asia Quarterly, 10, no. 1 (Winter 2006), 15–24, archived at: https://web.archive.org/web/20061206011820/http://www.asiaquarterly.com/content/view/166/43/

Islamic education for Chinese Muslims in the PRC and abroad was drastically affected by the Global War on Terror. Worldwide perceptions of Islamic education changed, particularly the perception of Islamic education in Arab states. In China, the government viewed Islamic education, particularly in the Uyghur Region, as a source of insecurity. Officials repackaged the rhetorical issue of “separatism” alongside terrorism and extremism.

Overwhelmingly, access to Islamic education in the Uyghur Region began to taper off in the early 2000s. Youth were banned from attending mosque prayers, as well as pursuing any kind of religious education in underground madrasas. The cessation of Islamic education and practice gained massive momentum after the declaration of the “People’s War on Terror” in 2014 and the Strike Hard Against Violent Terrorism campaign the same year.54Dilmurat Mahmut, “Controlling Religious Knowledge and Education for Countering Religious Extremism: Case Study of the Uyghur Muslims in China,” Forum for International Research in Education, 5, no. 1 (2019): 22–43. This pivot towards the repression of Islam seems counterproductive, given the role that international Islamic exchange has and could still play in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).55Fuquan Li, “The Role of Islam in the Development of the ‘Belt and Road’ Initiative,” Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, 12, no. 1, (2018).

[T]his unusually large number of students “prompted the embassy to coordinate with Beijing to act swiftly and stem the number of students […]”

China’s approach to overseas religious education in Arab states has taken a dramatic turn over the past four years. In Egypt, the trouble began in September 2016, according to the local Uyghur community. Sheikh Mahmoud Muhammed, the trustee of the Association of Muslim Scholars of East Turkistan, who lived in Egypt during this period, claims that the Chinese embassy in Cairo was alarmed when Egyptian security services approved 600 Uyghur students to study at Al-Azhar, bringing the total number of students there to 3,000 by 2017. Muhammed says that this unusually large number of students “prompted the embassy to coordinate with Beijing to act swiftly and stem the number of students, fearing the increase might constitute a threat in the future.” Per Muhammad’s second-hand testimony, the Chinese government accused Al-Azhar of accepting Chinese students without the government’s approval.56Khaled al-Masry, “Uighur Muslims in Egypt: A Welcoming Journey Ending with Deportation,” Daraj, January 23, 2020, https://daraj.com/en/49283/ We interviewed an anonymous Uyghur student who also made the claim that there were 3,000 Uyghur students of Islamic sciences and Arabic language at Al-Azhar University.57Anonymous Uyghur Student. Interview by Lucille Greer. Online voice chat. Washington, DC, May 6, 2021. Sara Gabr, with the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms (hereafter “Egyptian Commission”), documented cases during the crackdown and echoes this as a possible cause espoused by the larger Egyptian Uyghur community.58Sara Gabr, Egyptian Commission on Rights and Freedoms. Interview by Lucille Greer. Online video chat. Washington, DC, June 10, 2021.

In May 2017, students studying abroad began receiving calls from Chinese authorities to return to the Uyghur Region by the end of the month lest they suffer consequences. As students began to hear about detentions, many vowed to remain in Egypt until their school term ended, or even attempted to flee into Turkey where they were stopped by border guards.59“Uyghurs Studying Abroad Ordered Back to Xinjiang Under Threat to Families,” Radio Free Asia, May 9, 2017, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/ordered-05092017155554.html In June, Uyghurs in Egypt began receiving calls that their family members back home would be arrested if the students did not return, according to Gabr.60Sara Gabr, Egyptian Commission on Rights and Freedoms. Interview by Lucille Greer. Online video chat. Washington, DC, June 10, 2021. Bai Kecheng, chairman of the Chinese consulate-affiliated Chinese Students and Scholars Association in Egypt, meanwhile, denied any knowledge of the orders for Uyghurs to return.61Ibid.

Our anonymous student interviewee relayed that Uyghur students heard that trouble was coming a month or two before July. That April, the PRC banned beards, traditional Islamic baby names and Hijabs in the Uyghur Region, a dark portent for what was to come domestically and abroad. Uyghur students in Egypt exchanged messages over WhatsApp or in hushed conversation as they went about their daily lives, questioning whether the rumors that China was coming for them were true. Some chose to flee Egypt for Turkey or other countries, but most stayed. Some had been legal residents in Egypt for over a decade. They believed that they would be safe and far from China’s persecution at Al-Azhar. The interviewee was astonished when the police came for them.62Anonymous Uyghur Student. Interview by Lucille Greer. Online voice chat. Washington, DC, May 6, 2021. The Uyghurs Gabr spoke with also had believed that Al-Azhar would protect them. Furthermore, Gabr relayed that Uyghurs were arrested as early as April. Men were arrested and disappeared while women and children were allowed to flee to Turkey. By her unverified tally in the summer of 2017, between 400 and 500 detentions occurred in the few months before the crackdown in Cairo. During this time, an estimated 194 arrests occurred in Mansoura, which hosts a satellite campus of al-Azhar.63Sara Gabr, Egyptian Commission on Rights and Freedoms. Interview by Lucille Greer. Online video chat. Washington, DC, June 10, 2021. We have been unable to independently verify this number.

By July 2017, Egyptian security forces were arresting dozens of Uyghurs, most of them Al-Azhar students in Cairo. Initial estimates based on Arabic-language reporting suggested that 70 Uyghurs were arrested that month around the Nasr City district of Cairo, while 20 others were arrested at the Burj al-Arab Airport in Alexandria. Additional reporting has since placed this figure at 200 arrests total.64“Uyghurs Arrested in Egypt Face Unknown Fate,” Al Jazeera, July 27, 2017, https://www.al jazeera.com/features/2017/7/27/uighurs-arrested-in-egypt-face-unknown-fate The Egyptian Commission on Rights and Freedoms had the same unverified tally.65Sara Gabr, Egyptian Commission on Rights and Freedoms. Interview by Lucille Greer. Online video chat. Washington, DC, June 10, 2021. The security crackdown truly began on July 3, 2017, as police raided a popular Cairo Uyghur restaurant Aslam. The detainees were initially held in the police stations of Nasr City I and II, Elkhalifah, Elsalam II, El Nozha, and Heliopolis, according to reports at the time.66“Uyghurs Arrested in Egypt Face Unknown Fate,” Al Jazeera, July 27, 2017, https://www.al jazeera.com/features/2017/7/27/uighurs-arrested-in-egypt-face-unknown-fate In this round of arrests/detentions, women and children as young as fourteen and fifteen were arrested.

In this round of arrests/detentions, women and children as young as fourteen and fifteen were arrested.

In a June 2021 interview, Gabr told us that 70 Uyghurs had been detained in the Nasr City police station and 80 at Elkhalifah. The Uyghur detainees she was in contact with reported that Chinese officers conducted group interrogations in Mandarin and struck detainees in front of each other. Most of the people in these interrogations were forced to sign papers confessing their involvement with terrorist groups. In addition to police stations, several Uyghurs were taken to the Mogamma, a catch-all administrative building that handles paperwork for foreign residents. Officials there deported Uyghurs who had no legal status to China and canceled the legal status of others before sending them to third countries. From the police stations, some Uyghurs were singled out by Chinese officials, made to sign papers confessing terrorist associations, handcuffed and blindfolded, and sent to the Chinese embassy, where they were interrogated and then disappeared. The Egyptian Commission on Rights believes at least three were deported to China and then executed, although they have been unable to verify these details.67Sara Gabr, Egyptian Commission on Rights and Freedoms. Interview by Lucille Greer. Online video chat. Washington, DC, June 10, 2021. We have been unable to independently verify the claim thus far.

Our anonymous interviewee stated the largest wave of detentions occurred around 9:00 p.m. on July 4. Police came for Uyghur students in their houses, in restaurants, and on the streets. They raided Masjid Musa, the main mosque for Cairo’s Uyghur community.68Anonymous Uyghur Student. Interview by Lucille Greer. Online voice chat. Washington, DC, May 6, 2021. Gabr heard reports of two Uyghur men arrested at a mosque but was unable to verify details at the time.69Sara Gabr, Egyptian Commission on Rights and Freedoms. Interview by Lucille Greer. Online video chat. Washington, DC, June 10, 2021. Some students were able to hide in other districts of the city, as District Seven—Nasr City—was known as a Uyghur neighborhood. Friends and classmates called made phone calls and exchanged messages on WhatsApp, desperate to find out if they were safe.70Anonymous Uyghur Student. Interview by Lucille Greer. Online voice chat. Washington, DC, May 6, 2021. Gabr, whose grandfather owned a building on a majority-Uyghur street, recalls seeing Uyghur women and children running in the night as police cars circled.71Sara Gabr, Egyptian Commission on Rights and Freedoms. Interview by Lucille Greer. Online video chat. Washington, DC, June 10, 2021.

Security forces had reportedly gained information on where Uyghurs were living from landlords and real estate brokers. After entering their homes and arresting them, the police confiscated students’ personal effects, including cell phones, laptops, and books, and searched for hints of “extremist” ideology, according to Abd al-Akhir, a former student who fled Egypt. Al-Akhir said in an interview in 2020, “When the campaign was launched, I was outside with my family and one of my friends called and warned me about it. I spent several nights, with my wife and three children, running away from Cairo. I ended up staying in the countryside with one of my teachers. We knew about a certain ‘wanted’ list at the airport. I was scared, thank God I wasn’t on that list and fled to safety.”72Khaled al-Masry, “Uighur Muslims in Egypt: A Welcoming Journey Ending with Deportation,” Daraj, January 23, 2020. https://daraj.com/en/49283/

Gabr also believes that the authorities were targeting a specific list of names. In her estimation, security officials would go to one address to arrest a specific individual. If that individual was not present, they picked up whoever was at the time. Sometimes, the police came to Uyghur houses with instructions such as you have three or four days to gather your money and your papers, and get out. Gabr told us that 30 Uyghurs were arrested at Cairo International Airport; three to five were arrested at Burj Al-Arab International Airport in Alexandria, and three were arrested at Hurghada International Airport near Sharm el-Sheikh as they attempted to flee the country. Gabr theorized that the arrests outside of Cairo could be due to the presence of Al-Azhar University satellite campuses in Alexandria that might have hosted Uyghur students. Political refugees in Egypt commonly use airports outside of Cairo to escape, as there may be a smaller security presence outside of the capital. The Egyptian Commission on Rights and Freedoms, along with other organizations, attempted to send lawyers to the airports to assist fleeing Uyghurs but were turned away in most cases.

Sometimes, the police came to Uyghur houses with instructions such as you have three or four days to gather your money and your papers, and get out.

While most Uyghurs stopped at the airport were allowed to flee to Turkey or Malaysia, three or four were sent to China by Gabr’s count. The Egypt Commission, working with Amnesty International, verified that twelve people were extradited back to China in the July 2017 crackdown. Gabr suspects that the actual number was much higher.73Sara Gabr, Egyptian Commission on Rights and Freedoms. Interview by Lucille Greer. Online video chat. Washington, DC, June 10, 2021. A later bulletin from Amnesty International put the total number of deportations at 22.74Amnesty International, “Egypt: Further information: More Uighur students at risk of forcible return,”August 1, 2017, https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/MDE1268482017 ENGLISH.pdf The Commission’s source, a Uyghur detainee who sometimes had access to a phone while in police custody, disappeared in October that year. We have had limited information access since. As Uyghurs fled Egypt or went into hiding, following up on the fates of detainees became extremely challenging. The crackdown drastically diminished the once-vibrant Uyghur communities in Cairo and elsewhere.75Sara Gabr, Egyptian Commission on Rights and Freedoms. Interview by Lucille Greer. Online video chat. Washington, DC, June 10, 2021. On the basis of data in our China’s Transnational Repression Dataset, we estimate 274 cases of Uyghur detentions and deportations have occurred from Egypt since 2001.

We learned in another interview that Chinese police coordinated their crackdown in Dubai to round up Uyghur students who attempted to enter the UAE after fleeing the crackdown in Egypt.76Maryam (Pseudonym), a Uyghur living in the United Arab Emirates. Interview by Bradley Jardine. Online video chat. Washington, DC, June 25, 2021. Maryam (pseudonym) had been working in the UAE since 2012. In 2017, she witnessed Chinese security services attempting to intercept Uyghurs in Dubai who had fled the crackdown at Al-Azhar. According to Maryam, Chinese officers entered a Uyghur restaurant in Dubai where she was eating and showed patrons photographs of Uyghur “fugitives” from Egypt in a bid to gain information about their current whereabouts.77Ibid. “We were all so shocked!” she told us. Maryam’s account speaks to how China’s security services coordinate their activities across Arab states, as elsewhere, to find and coerce Uyghurs living abroad. Uyghurs who flee from one country into a second and even a third are at risk of relentless surveillance and pursuit. As a result, Uyghurs fleeing across sovereign boundaries, often at great risk to themselves and their families, are unable to escape the reach of the Chinese government.

Maryam’s encounters with the police did not stop at her experience in the Dubai restaurant. She told us:

Chinese officers also visited the house I was living in with other Uyghurs. They said the owner gave them an advertisement to rent rooms and that they wished to inspect the building. The owner is our friend, however, and we called to ask whether she had given them permission to enter. She said no such permission had ever been given and instructed us to refuse them entry.

According to Maryam, other Uyghurs in her district had similar encounters with plainclothes officers during that time.78Ibid.

A security source explained the crackdown during statements to Egypt’s al-Masry al-Youm newspaper days later on July 9, 2017, saying,

[I]t comes within the framework of normal security procedures carried out by security authorities in the country to check the residences of foreigners, and that preliminary investigations and examination of seized papers indicated that a number of them violated conditions of residence in the country.79Asam Abu Sadira, “[A security source denies the deportation of “Uyghur students”: normal procedures for examining the papers of foreigners] مصدر أمني ينفي ترحيل «طلاب الإيغور»: إجراءات طبيعية لفحص أوراق الأجانب,” al-Masry al-Youm, July 9, 2017, https://www.almasryalyoum.com/news /details/1160174

This argument does not stand up to scrutiny, however, since Egypt authorities have never undertaken a crackdown this severe against other groups of foreign students. The same source denied news of the deportation of any Uyghurs to China. Our data records at least 46 fully verified cases in which Uyghur students were coerced to leave or deported from Egypt and then arrested on arrival to another country, with an additional 30 students whose details after detention remain unclear. Some of those students who “chose” to leave, such as Sami Bari, have faced particularly harsh sentences. Sami, a student who left Egypt after receiving a call to return home, was later sentenced to life imprisonment.80“Uyghur Group Defends Detainee Database After Xinjiang Officials Allege ‘Fake Archive,’” Radio Free Asia, February 11, 2021, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/database-02112021174942.html

Our data records at least 46 fully verified cases in which Uyghur students were coerced to leave or deported from Egypt and then arrested on arrival to another country, with an additional 30 students whose details after detention remain unclear.

Initially, Al-Azhar denied news of the mass arrests. The Al-Azhar Media Centre released a statement saying, “The Al-Azhar Media Centre watched closely the news circulated on social media websites of arrests of Turkestani students, and denied the arrest of any students inside the Al-Azhar University campus or any of the Al-Azhar institutes.” However, a consultant to Al-Azhar, Mohammad Muhani, confirmed that something unusual occurred, stating on Egyptian television that “forty-three people were arrested, including three Al-Azhar students.”81Khaled al-Masry, “Uighur Muslims in Egypt: A Welcoming Journey Ending with Deportation,” Daraj, January 23, 2020. https://daraj.com/en/49283/ Organizations like the Egyptian Commission and members of the Uyghur community attempted to reach out to the administration at Al-Azhar but received no response.82Sara Gabr, Egyptian Commission on Rights and Freedoms. Interview by Lucille Greer. Online video chat. Washington, DC, June 10, 2021.

The Egyptian press offered only minimal coverage of the crackdown. A commentary piece ran in al-Masry al-Youm claimed it was China’s natural right to protect its own security and this was not an Egyptian problem. It also added that Uyghur students should have listened to their government’s orders to return home months ago and thus avoided this treatment.83Islam al-Ghazouli, “[Chinese Crisis] أزمة صينية,” al-Masry al-Youm, July 22, 2017, https://www.al masryalyoum.com/news/details/1166250 China’s hand in the events at Al-Azhar was further fueled by news from June of a security agreement signed between the Egyptian Ministry of the Interior and the PRC’s Ministry of Public Security, as well as of reports of Chinese security personnel present during interrogations.84“‘They are Not Welcome Here’: Report on the Uyghur Crisis in Egypt,” Freedom of Thought and Expression Law Firm, October 1, 2017, https://afteegypt.org/en/academic_freedoms/2017/10/01/ 13468-afteegypt.html The Egyptian Interior Minister, Magdy Abdel Ghaffar, met with China’s Deputy Minister of Public Security, Chen Zhimin, during his visit to Cairo in June 2017. According to a statement from the Egyptian government, they discussed a number of specialized security fields, including the spread of terrorism and extremist ideologies during their visit.85“Egypt, China sign technical cooperation document in specialized security fields,” State Information Service, June 20, 2017, https://www.sis.gov.eg/Story/114496 Gabr also tied arrests to this visit in her assessment of the timeline of events.86Sara Gabr, Egyptian Commission on Rights and Freedoms. Interview by Lucille Greer. Online video chat. Washington, DC, June 10, 2021. Given Beijing’s longstanding attitude that Uyghurs are a “terrorist threat” and the fact that the crackdown occurred just one month after this visit, we find it likely that officials discussed the status of Uyghur students at Al-Azhar University during Chen’s visit to Cairo.

Pilgrimage as a Tool of Control

China seeks to control the Hajj to insulate its Muslim population from the wider Islamic community. The Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina, the holy cities of Islam, is one of the five sacred pillars of the Muslim faith. Muslims are expected to take part at least once in their lifetimes if they are able. Muslims from China have made the trek to the Arabian Peninsula for centuries. Among the most famous are the accounts of Zheng He, a Chinese Muslim sailor who made four voyages to the Arabian Peninsula in the fifteenth century.87Hyunhee Park, “Mapping the Chinese and Islamic Worlds: Cross-Cultural Exchange in Pre-Modern Asia,” Cambridge University Press, (September 2012), https://www.cambridge.org/core/ books/mapping-the-chinese-and-islamic-worlds/9554FAD722664734198974578D239BAD

China’s Party-state tightly controls the number of its Muslim citizens permitted to undertake religious pilgrimage. According to Uyghur activists, the majority of permits to Mecca, part of a quota system set by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, go to government officials and security guards accompanying the Hajj delegation from China. Although several international human rights declarations and covenants call on signatories and parties to allow citizens freedom of movement (see, e.g., Article 12 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Article 13 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights88The PRC has ratified the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It is a signatory of International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights but has not ratified it. As a signatory, China has the obligation to act in good faith and not defeat the purpose of the ICCPR.), Chinese law limits its Muslims citizens’ participation in the Hajjto state-sponsored pilgrimages to Mecca. The 2001 XUAR Regulations on the Management of Religious Affairs restrict the movement of Muslims more explicitly by specifying that “pilgrimage activities are to be organized by the religious affairs departments of the people’s governments and religious organizations. No other organization or individual may organize such activities.”89“Xinjiang Police Reportedly Bar Uyghur Hajj Pilgrimage by Confiscating Passports,” U.S. Congressional-Executive Commission on China, October 26, 2005, https://www.cecc.gov/publi cations/commission-analysis/xinjiang-police-reportedly-bar-uighur-haj-pilgrimage-by

The Religious Affairs Bureau is charged by the State Council with overseeing China’s participation in the Hajj. All seven agencies of the Religious Affairs Bureau are responsible for coordinating the process with the Saudi government, and the Chinese Islamic Association is tasked with organizing and implementing it. All other agencies are forbidden from organizing Hajj, Umrah, or disguised Hajj activities under any name or form.90Ibid. These restrictions are stipulated in the Regulations on Religious Affairs, a document released by the State Council in 2004.91“Regulations on Religious Affairs (Chinese and English Text),” Congressional-Executive Commission on China, February 9, 2011, https://www.cecc.gov/resources/legal-provisions/regulations-on-religious-affairs The document includes provisions stating that agencies of the Religious Affairs Bureau are responsible for halting unauthorized Hajj-organization for pilgrims. The “Provision on Forbidding Travel Agencies to Organize Go-Abroad Individual Hajj” (2005) identified the Hajj as “a political and policy-oriented religious activity associated with national unity, social stability, national security, and our country’s international image.”92Ibid.

Beijing took Hajj restrictions a step further by building on its ties with Saudi Arabia to regulate the activities of third-party countries issuing travel documents. In 2006, Uyghur Muslims who had traveled to Pakistan seeking to undertake the Hajjpilgrimage—according to one estimate, as many as 6,000 in Rawalpindi—were refused visas by the Chinese Embassy in Islamabad, who was allegedly coordinating with its Saudi counterpart.93“East Turkestan: Pilgrims Denied Saudi Visas in Pakistan,” UNPO, September 21, 2006, https://unpo.org/article/5486 Uyghurs were told to return to China or face consequences including loss of government posts, loss of pensions for retirees, and punishment of family members. A senior Saudi official allegedly emerged from the Saudi Embassy and told protesters outside that it was not Saudi policy to deny visas to Muslims, but that the Saudi government was abiding with a Chinese request to not issue visas to Uyghurs. This policy change disrupted the usual overland route Uyghur Muslims took to Mecca and Medina. Now that Uyghurs could only apply from within the PRC, China could better control who could undertake Hajj and monitor them as they did so.

Uyghurs were told to return to China or face consequences including loss of government posts, loss of pensions for retirees, and punishment of family members.

China’s sharp securitization of policy with the 2014 “People’s War on Terror” unleashed a raft of surveillance methods, putting serious pressure on the Hajj. XUAR police used the religious pilgrimage as an excuse to monitor and surveil participating Uyghurs. In August 2018, exactly 11,500 Chinese Muslims were expected to perform the Hajj. Before leaving the country, some of the pilgrims were given state-issued tracking devices in the form of “smart cards” attached to lanyards around their necks.94Eva Dou, “Chinese Surveillance Expands to Muslims Making Pilgrimage to Mecca,” Wall Street Journal, July 31, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinese-surveillance-expands-to-muslims-making-mecca-pilgrimage-1533045703 The devices bore GPS trackers and customized personal data. The state-run China Islamic Association defended the trackers, stating that they were intended to ensure the pilgrims’ safety; stampedes at the Hajj have sometimes turned deadly and caused international incidents.95Ruth Graham, “The Hajj Stampede: Why Do Crowds Run?” The Atlantic, September 26, 2015, https://www. theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/09/hajj-stampede-crowd-disasters/407542/ However, Human Rights Watch noted that China monitors Uyghur pilgrims not out of fear for individuals’ safety because officials fear that religious pilgrimages could act as a “potential cover for subversive political activity.”96Human Rights Watch, “One Passport, Two Systems: China’s Restrictions on Foreign Travel by Tibetans and Others,” July 13, 2015, https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/07/13/one-passport-two-systems/chinas-restrictions-foreign-travel-tibetans-and-others In the context of China’s systematic campaign to eradicate expressions of Uyghur identity, restrictions on the Hajj cannot be isolated from the ongoing genocide in the Uyghur Region.97Human Rights Watch, “‘Break Their Lineage, Break Their Roots’: China’s Crimes Against Humanity Targeting Uyghurs and Other Turkic Minorities,” April 19, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/04/19/break-their-lineage-break-their-roots/chinas-crimes-against-humanity-targeting

The use of Chinese surveillance technology is a unique feature in the period of transnational repression from 2014 to the present. With companies like Huawei expanding their footprints in Mecca and Medina, China has the opportunity to mine data of Muslim pilgrims and their contacts in the PRC. In 2016, the Saudi Ministry of Interior and Huawei collaborated to build a Unified Security Operations Center (911) to handle emergency calls during the Hajj season, the volume of which is a perennial problem for Saudi telecommunications infrastructure.98“2017 Annual Report,” Huawei, https://www.huawei.com/-/media/corporate/pdf/annual-report/annual_report2017_en.pdf?la=en While Huawei claims it does not produce surveillance technology, the company’s collaboration with Saudi authorities is important to monitor given the ability of the Party-state to utilize data connections to Saudi Arabia in order to repress Uyghurs and other Muslims in China. In 2019, a Muslim Uyghur was stopped at mainland China’s border with Hong Kong and interrogated for three days because someone on his WeChat contact list had “checked in” at Mecca. The authorities expressed concern that the person had traveled on an unofficial pilgrimage to Mecca, a crime under Chinese law.99Sarah Cook, “Worried about Huawei? Take a Look at Tencent,” Freedom House, March 29, 2019, https://freedomhouse.org/article/worried-about-huawei-take-closer-look-tencent? Should a pilgrim call 911 during Hajj or download an app during their visit, there could be consequences for them or their relatives in the XUAR.

The PRC is gathering biodata from Uyghurs in Arab states as a part of the Chinese securitization of Hajj. Ahmad Talip (AKA Ahmetjan Abdulla), who was arrested in 2018 in Dubai after going to a local police station to collect documents for his brother, told his wife that the Dubai police had taken a blood sample from him at the request of the Chinese government. A Dubai court judged that he should be freed, but when his wife Amanissa Talip went to pick him up, she learned he had been moved to a different prison and was in Interpol custody. She unsuccessfully appealed to Interpol and the UN to have him released, and officials in Dubai threatened to detain her and their entire family and deport them to China if she continued to press the case. Mr. Ahmad was transferred again; his wife has not heard from him since. She was told that he was deported to China and imprisoned two days after his last transfer.100“Uyghur Speaks Out About Husband’s ‘Deportation’ From UAE,” Middle East Eye, February 8, 2021, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/uighur-speaks-out-against-husbands-deportation-uae

In 2019, a Muslim Uyghur was stopped at mainland China’s border with Hong Kong and interrogated for three days because someone on his WeChat contact list had “checked in” at Mecca.

The Party-state has also used the Hajj as a mechanism to coerce Uyghurs residing in safer European jurisdictions to fly to Saudi Arabia where they are at risk. Norway-based Uyghur Omer Rozi said his mother was forcibly taken on Hajj by Chinese security services.101Omer Rozi, “Witness Statement – Summary Witness Statement,” Uyghur Tribunal, https://uyghurtribunal.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/06-1225-JUN-21-UTFW-030-Omer-Rozi-English.pdf Once in Saudi Arabia, she called her son three times per day, urging him to join her. He refused. During their final phone call, he heard someone in the background yelling at her, confirming his suspicions that the entire operation was forced. He reportedly arranged for a friend of his from Norway to visit his mother, where he was surveilled by the intelligence agents who had accompanied her. Police later called him and issued four conditions for the release of his mother and two siblings who had also been detained: 1) do not buy a mosque in Norway; 2) avoid the Norwegian Uyghur diaspora; 3) do not send monetary aid to organizations in Turkey; and 4) take photos and collect intelligence for the police.102Ibid.

In October 2020, the State Administration of Religious Affairs, subordinate to the United Front Work Department), published the document “Measures for the Administration of Islamic Hajj Affairs.” The measures detail regulations in 42 articles, which came into force on December 1, 2020. The measures are restrictive, limiting Hajj to pilgrims over the age of 60; they also stipulate that Hajj applicants are subject to security checks by Chinese authorities before being granted permission to travel to Mecca. Uyghurs who are accepted are expected to undergo courses in reeducation centers, deterring many from applying. Regional and local quotas were established for Chinese pilgrims allowed to go to Mecca in these measures. All pilgrimages were to be organized and managed by the Chinese Islamic Association with criminal charges applied to those who did not.103“Pilgrimage to Mecca Only Allowed for ‘Patriotic’ Chinese Muslims,” World Uyghur Congress, October 13, 2020, https://www.uyghurcongress.org/en/pilgrimage-to-mecca-allowed-only-for-patriotic-chinese-muslims/ Article 12.1 provides that the religious and social life of the candidate to Hajj will be examined, and only those found to be “patriotic and of good conduct” will be eligible.

These regulations, combined with the ability of authorities in the PRC to track and surveil pilgrims to Mecca, have turned the Hajj into yet another tool of control and surveillance. Because a limited number of Chinese Muslims can still make the trek to Mecca, the Party-state is able to claim that they have guaranteed religious liberty to Muslim citizens of the PRC. Most Chinese Muslims would prefer not to submit the application and have their “patriotic” attitudes and loyalty to the Party scrutinized. Anyone considering “unofficial” pilgrimages faces criminal penalties.

Passport Weaponization

Passports are notoriously difficult for Uyghurs to obtain, and recent refugee crises have caused recalibration of the state’s approach to passport policies. As many as 30,000 Uyghur refugees arrived in Turkey between 2010 to 2016, both from human trafficking networks across Southeast Asia and a short-lived period in 2015–16 in which XUAR authorities relaxed passport application requirements for Uyghurs across the region. As Sean Roberts notes, this period of relative relaxation allowed Uyghurs to flee to Turkey.104Sean Roberts, The War on the Uyghurs: China’s Internal Campaign against a Muslim Minority (Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press), 2020, 186. Although the reasons for this seemingly accommodationist and short-lived Chinese policy remain unknown, Roberts suggests it may have been an early effort to assist regional surveillance, as passport applications in the Uyghur Region required biometric data, voice samples, and 3D images.105Ibid. By late October 2016, the policy was reversed and it again became extremely difficult for Uyghurs to receive passports; many had their passports taken by the Xinjiang PSB for “safekeeping” beginning that Fall. Efforts to control Uyghur mobility have also grown more draconian. Police documents leaked from the XUAR detention facilities in Qaraqash County suggest that between 2017 and 2019, some Uyghurs were sent to re-education centers merely for applying for passports.106Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Ideological Transformation: Records of Mass Detention from Qaraqash, Hotan,” February 2020, https://docs.uhrp.org/pdf/UHRP_QaraqashDocument.pdf Around the world, meanwhile, embassy officials routinely inform overseas Uyghurs the only way to renew their passports is to return to China using government-issued one-way travel documents back to the Uyghur Region, where they face arbitrary arrest or detention.107Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Weaponized Passports: The Crisis of Uyghur Statelessness,” April 1, 2020, https://uhrp.org/report/weaponized-passports-the-crisis-of-uyghur-statelessness/ Passport processes and policies in China facilitate its system of mass surveillance in defiance of international law.108Ibid.

These practices have also impacted the Uyghur community in Arab states. According to an anonymous informant, Uyghurs residing in Saudi Arabia claimed that in January 2020, the Chinese Embassy in Riyadh had refused to issue any passports to their community since 2018, supplying only one-way travel documents back to China.109“Uyghurs in Saudi Arabia Flee to Turkey as Chinese Embassy Ends Passport Renewals,” RFA, January 31, 2020, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/turkey-01312020165513.html According to the same informant, Uyghur students in Saudi Arabia sent a letter to the Chinese consulate in Jeddah asking why passports had been issued but received no response.

Uyghurs residing in Saudi Arabia claimed that in January 2020, the Chinese Embassy in Riyadh had refused to issue any passports to their community since 2018, supplying only one-way travel documents back to China.