A Uyghur Human Rights Project report by Ben Carrdus. Read our press statement on the report; download the full report in English; and view a printable, one-page summary of the report.

Find coverage of the report in the New Humanitarian.

I. Key Takeaways

- In numerous countries around the world, Uyghur and other Turkic refugees from East Turkistan are living in peril of refoulement because of undue influence from China on governments and immigration authorities in the Uyghur refugees’ host countries;

- The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is in a number of situations unable to provide meaningful protection to Uyghur refugees, partly as a consequence of Chinese interference, partly as a consequence of UNHCR shortcomings;

- In the absence of adequate international protection from UNHCR, national governments are morally obligated to step up to provide contingencies for safe haven for Uyghur refugees;

- Uyghur refugees are facing an unprecedented campaign of harassment and intimidation in the form of China’s transnational repression, rendering Uyghur refugees as potentially the most at-risk refugee population in the world in a non-militarized context. Many are effectively stateless;

- Several governments around the world, including the U.S. and Canadian governments, have recognized the perils facing Uyghur refugees escaping the genocide in East Turkistan, and are offering the prospect of resettling a significant number of Uyghur and other Turkic refugees;

- The U.S. already has the systems in place to accept Uyghur and other Turkic refugees into the United States Refugee Admissions Program, and there is a well-established Uyghur community already in the U.S. willing and able to assist in settling Uyghur refugees via the Welcome Corps;

- The number of at-risk refugees from East Turkistan in second countries around the world is estimated to be much smaller than other crises receiving international assistance, numbering in the low hundreds in some cases, making the prospect of de-escalating the crisis a very real possibility.

II. Summary

The urgency of a response to the plight of Uyghur refugees around the world is growing. In many countries, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is unable to fulfill its mandate for a variety of interrelated reasons: the host country is not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention; the host country places limits on UNHCR’s reach; or UNHCR’s efforts are ineffective and there are no contingencies in place to provide protections to refugees. Amid concerns about the insufficiency of international protections, the Chinese government’s economic and diplomatic enticements are rendering Uyghur refugees in second countries ever more prone to refoulement under bilateral agreements and informal arrangements brokered with Beijing. Despite an authoritative body of evidence documenting the scale and severity of human rights violations in the Uyghur Region,1See, for example, “Assessment of Human Rights Concerns in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China,” Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), August 31, 2022, online; “CECC Annual Report 2022 – Xinjiang,” Congressional-Executive Commission on China, November 16, 2022, online; and UHRP’s archive of published research online. Beijing expects host countries to deport Uyghur refugees on demand. And meanwhile, China continues to harass and intimidate Uyghur refugees around the world, which includes the punishment of Uyghur refugees’ family members still in East Turkistan.2The toponyms “East Turkistan” and “Uyghur region” are used in this report, which along with “the Uyghur homeland” are preferred by the vast majority of Uyghurs over “Xinjiang” and the “Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region,” which are regarded as colonial terms. In cases where we cite particular publications or refer to government offices and apparatuses, however, we use “Xinjiang” or related forms such as “Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region” or “the XUAR.” See also: “Decolonizing the Discussion of Uyghurs: Recommendations for Journalists and Researchers,” Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP), December 21, 2022, online.

The United States was the first country to determine that China’s policies and practices in East Turkistan amount to genocide.3Benjamin Fearnow, “United States Becomes First Country in World to Declare China’s Uighur Treatment Genocide,” Newsweek, January 19, 2021, online. Having done so, the U.S. Congress duly designated at-risk Uyghur refugees as one of several populations deserving “priority consideration” for resettlement in Fiscal Year 2023.4“Report to Congress on Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2023,” United States Department of State, September 8, 2022, online. Similarly, the Canadian parliament voted to recognize China’s treatment of Uyghurs and other Turkic people in East Turkistan as genocide, and a parliamentary motion was passed in February 2023 pressing the Canadian government to “urgently leverage” its refugee program to “expedite the entry of 10,000 Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims in need of protection, over two years starting in 2024.”5See: “H.R.1630 – Uyghur Human Rights Protection Act,” 117th Congress (2021-2022), March 8, 2021, online; “UHRP Commends Canada for Progress on Uyghur Resettlement, Urges Concerned Governments to Consider Similar Measures,” UHRP, February 1, 2023, online.

Beijing expects host countries to deport Uyghur refugees on demand.

These encouraging developments have the potential to de-escalate the crisis facing Uyghur refugees around the world. With the intention of informing and encouraging upcoming debates in the U.S. Congress and other national legislatures on accepting Uyghur, Kazakh and other Turkic refugees who face persecution if deported to China, UHRP interviewed 11 Uyghur refugees in three countries to highlight the barriers they face in finding safe haven and resettlement. The main themes to emerge were the profound fears endured by the interviewees that they will be deported to the People’s Republic of China (PRC); the intense stress of worrying about family members remaining in the Uyghur homeland; the overwhelming sense of helplessness, frustration and despair that comes from seeing no prospect of safe refuge or betterment for themselves and their families; and a crucial common experience highlighted in this report: the extremely limited role that UNHCR has played in their cases.

It should be noted that the number of at-risk refugees from East Turkistan is relatively modest, and there is significant potential, therefore, for the crisis they face to be resolved. According to estimates from community leaders and NGOs, aside from Turkey with an estimated population of around 10,000 Uyghur refugees, there are thought to be only 100–300 at-risk refugees in each of a dozen or more countries around the world.6This estimate is based on conversations and correspondence with several individuals in late 2022 and early 2023.

However, in spite of the low numbers, the severity of risk is high. Human rights conditions in East Turkistan constitute atrocity crimes: the Chinese authorities subject at-risk Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples to cross-border harassment and refoulement precisely because they are escapees from an ongoing genocide. As such, low numbers are evidence of the severity of the crackdown, and it is wholly within the power of responsible states to rescue these individuals.

III. Methods

In September and October 2022, UHRP interviewed 11 Uyghur refugees: six in Turkey, four in Pakistan, and one in India. The interviews were conducted in the Uyghur language by a UHRP researcher and an experienced interpreter on UHRP’s staff, using a smartphone app with end-to-end encryption. The interviews were transcribed and then edited into first-person English based on notes taken by the interpreter and researcher.

UHRP is choosing not to directly identify the interviewees by name, or by extension, identify their family members still in East Turkistan. However, several of the interviewees have already been interviewed and identified in the international media while others are well-known in the Uyghur diaspora. Anyone familiar with their stories may recognize the individuals from details in this report. Nevertheless, UHRP has decided to avoid using their names, and for this report uses pseudonyms to conceal their identities.

IV. UHRP Interviewees

The Uyghur diaspora is widely dispersed throughout numerous countries and many individuals are profoundly fearful for the safety of themselves and their families. In consequence, UHRP’s interviewees are representative only of the small number of refugees willing and able to tell their stories. UHRP is choosing to report on these interviewees’ experiences as a means of spurring action to relieve acute needs that are apparent already, despite the research constraints.

All of the interviewees are male. They range in age from their early 30s to their late 60s. Ten of the 11 left East Turkistan during the years 2001 to 2016, and one left in 1976 when he was around two years old. His family fled to Afghanistan and then to Pakistan in the mid-80s.

Two of the interviewees left East Turkistan with their spouse and children, two others were later joined by their spouse and children, and the remaining seven either had to leave immediate family behind, or they have married and had children since leaving East Turkistan; two were unmarried when they left and remain unmarried.

UHRP’s interviewees are representative only of the small number of refugees willing and able to tell their stories.

Eight of the interviewees left the PRC for a second country with passports and visas. Of these eight, three left with no notion they would be unable to return: two originally left to further their religious studies (Memet in 2006 and Abdullah in 2001) and one originally left to visit a new-born grandchild in Turkey (Tahir in 2014). All three of these interviewees report that their eventual decision to remain abroad arose from seeing the fate of numerous family members and other acquaintances in East Turkistan. They either realized it wasn’t safe to return or they were urged by family members in East Turkistan not to return.

The remaining five who left with passports did so with the intention of escaping untenable lives in East Turkistan and with the objective of remaining abroad.

Of the three who left without passports, Ablimit left in 1976 when his family fled first to Afghanistan and then later to Pakistan; Aydin fled the PRC on foot through Tibet and over the Himalayas into Nepal in 2001, then later to India; and Perhat left in 2013 on foot into Thailand, then Malaysia, arriving in Turkey in 2014.

None of the interviewees hold a valid PRC passport any longer; in some cases, as with several of the Turkey-based interviewees, they simply allowed their passports to expire once they acquired the necessary documentation authorizing their presence in Turkey. However, several of the interviewees did attempt to renew their passports at Chinese consulates in Turkey and Pakistan, but Chinese consular officials either did not respond to their repeated applications, or they were told they would have to return to the PRC to renew their passports. Fearing being interned in a concentration camp if they did, they chose not to return. Three of the four Pakistan-based interviewees who do not have documents authorizing their presence in Pakistan have been rendered effectively stateless.7See: “Weaponized Passports: the Crisis of Uyghur Statelessness,” UHRP, April 1, 2020, online, and “Uyghurs to China: ‘Return our relatives’ passports,’” UHRP, August 6, 2020, online.

UNHCR in Host Countries

UNHCR was constituted to provide “international protection and humanitarian assistance, and to seek permanent solutions” for “all persons outside their country of origin for reasons of feared persecution, conflict, generalized violence, or other circumstances, [and who] require international protection.”8See: “Mandate of the High Commissioner for Refugees and His Office, Executive Summary,” UNHCR, accessed on March 27, 2023, online. UNHCR has been successful in preserving the lives and dignity of countless people since it was founded in response to the global refugee crisis following the end of the Second World War.

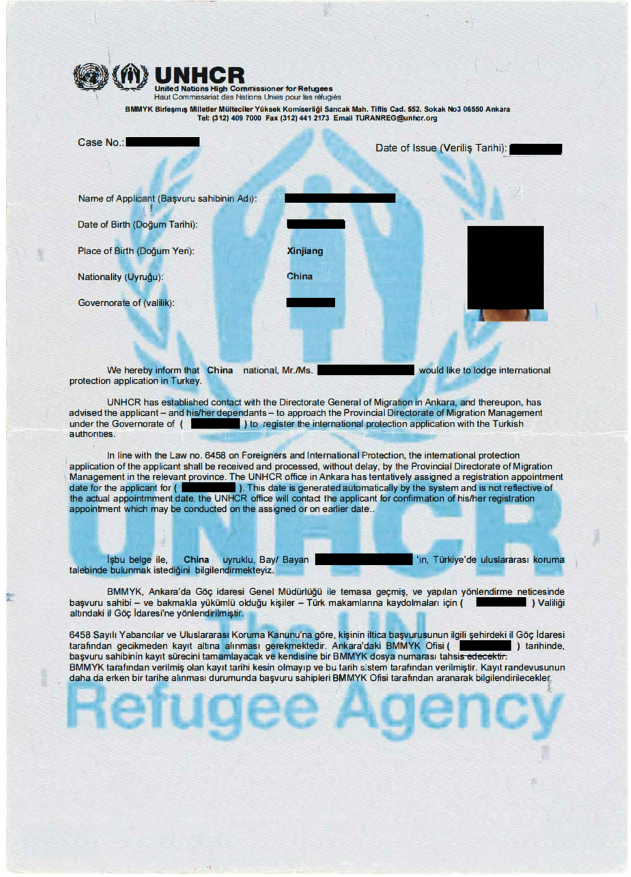

UNHCR works in countries around the world when invited by the host government to assist with the management of refugees within state borders. In addition, UNHCR is frequently able to provide rapid emergency humanitarian assistance in cases of war and natural disasters. Generally, and once conditions on the ground permit, UNHCR interviews people in need of protection in a process known as Refugee Status Determination (RSD) and then grants refugee status to those who meet the definition of a refugee as set out in international law.9“Handbook on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status under the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees,” UNHCR, accessed on March 27, 2023, online. UNHCR registers people formally recognized as refugees, which includes the issuance of a document intended to enable legal presence within a host country, and by extension, the document protects registered refugees from refoulement.10“Guidance on Registration and Identity Management,” UNHCR, accessed on March 27, 2023, online. Often in tandem with the host country’s own immigration authorities, UNHCR then seeks permanent settlement solutions for refugees, whether that be resettlement to a third country, settlement in the host country, or return to the country of origin when it is safe to do so.

They either realized it wasn’t safe to return or they were urged by family members in East Turkistan not to return.

This brief overview does not detail the diversity of political, military and environmental obstacles with which UNHCR contends to conduct its work. In many situations, UNHCR is prevented from carrying out its mandate. For example, in the cases of the Uyghur interviewees in this report, the host countries are either not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention, as in the cases of India and Pakistan, and therefore not directly obligated to accommodate UNHCR.11Nevertheless, whether or not a country is party to the 1951 Refugee Convention, countries still have a moral obligation to uphold the norms of other humanitarian instruments to which they are a party, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which guarantees the right of individuals to seek asylum from persecution. For a fuller discussion of international refugee law, see: “‘Nets Cast from the Earth to the Sky’: China’s Hunt for Pakistan’s Uyghurs,” UHRP, August 11, 2021, online. In a further example, states are a party to the Convention but with formal reservations, as with Turkey. Turkey abides by provisions in the 1967 Protocol to the Refugee Convention which effectively permits the exclusion of non-European people from formal definition as refugees.12See: James C. Hathaway, “Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees (1967),” The Rights of Refugees Under International Law, Cambridge University Press, January 6, 2010, online.

Nevertheless, the governments of these three countries still allow UNHCR to play specific yet significant roles within their borders. In Turkey, UNHCR has broad authority for the welfare of over three and a half million people who have fled the civil war in neighboring Syria,13“Turkey Policy Brief,” International Center for Migration Policy Development, January 2021, online. the largest refugee community in the world. UNHCR was also on the ground to provide substantial disaster relief in the wake of the February 2023 earthquakes in Turkey and Syria.14“UNHCR responds to deadly earthquakes in Türkiye and Syria,” UNHCR, February 7, 2023, online.

In September 2018, largely as part of an ongoing series of legal and institutional reforms tied to its E.U. accession negotiations, Turkey overhauled immigration practices in a move which largely excluded UNHCR from the processes of recognizing and registering refugees within the country, with the sole exception of Syrians.15See, for example: İbrahim Efe, Tim Jacoby, “‘Making sense’ of Turkey’s refugee policy: The case of the Directorate General of Migration Management,” Migration Studies, Volume 10, Issue 1, March 2022, p. 62–81, online. As a result, UNHCR has little practical role to play in regard to non-Syrian refugees, as in the cases of the Turkey-based Uyghurs interviewed for this report.

In India, UNHCR processes refugees on the basis of New Delhi’s own discretionary protocols. The Indian government grants UNHCR access to Rohingya refugees from Myanmar, and UNHCR assesses and issues documentation to Rohingya refugees intended to confer protections against refoulement.16Mahika Khosla, “The Geopolitics of India’s Refugee Policy,” Stimson Center, September 22, 2022, online. However, in March 2022, around 500 Rohingya refugees, including some with UNHCR refugee status, were under threat of refoulement by the Indian government,17“Rohingya Deported to Myanmar Face Danger,” Human Rights Watch, March 31, 2022, online. amid intense legal and political debate in India about refugees’ rights and government responsibilities.18Malcolm Katrakand and Shardool Kulkarni, “Refouling Rohingyas: The Supreme Court of India’s uneasy engagement with international law,” Journal of Liberty and International Affairs, Vol. 7, No. 2, June 22, 2021, online.

A case reported in India highlights the potential for Uyghurs to be refouled. Three Uyghur brothers, Salamu, Abdul Khaliq and Adil, who fled China together in 2013 are currently under threat of deportation. Captured by the Indian army in June 2013 in Ladakh after crossing from East Turkistan, they were handed over to the Indo-Tibetan Border Police. After two months of questioning, they were handed over to local police, who charged them in relation to entering India without valid travel documents and possession of knives, for which they were sentenced to 18 months in prison.19Umer Maqbool, “The Unknown Fate Of Uyghur Refugees Detained In India,” Fair Planet, May 16, 2023, online.

The brothers’ ages were listed by police at the time as being between 20 and 23 years, but later claimed they were between 16, 18, and 20.20Aakash Hassan, “Uighur siblings in India jail since 2013 face deportation threat,” Al Jazeera, June 6, 2023, online. The brothers reportedly completed their sentences in 2015, but were subsequently sentenced under Jammu and Kashmir’s Public Safety Act (PSA), a controversial preventative detention law which allows the government to detain persons for allegedly “disturbing the maintenance of public order.” Functionally, the PSA allows Indian authorities to keep individuals in detention for up to 12 months,21“A ‘Lawless Law’: Detentions under the Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act,” March 21, 2011, Amnesty International, online. but the brothers have been subject to rolling six-month detention orders since the end of their initial prison term in 2015.

China’s growing economic importance to Pakistan […] is seen by many observers as undermining any political or humanitarian will to recognize and duly protect Uyghur refugees.

In the latest detention order, Kashmiri authorities state that “it is necessary to detain the siblings under PSA until arrangements are made for their repatriation to their native country.” The Indian Home Ministry has already ordered their repatriation to China, which the siblings have challenged in court.22Umer Maqbool, “The Unknown Fate Of Uyghur Refugees Detained In India,” Fair Planet, May 16, 2023, online. UNHCR in New Delhi have reportedly stated that they cannot act on behalf of the brothers until they are released from prison.23Aakash Hassan, “Uighur siblings in India jail since 2013 face deportation threat,” Al Jazeera, June 6, 2023, online.

In Pakistan, UNHCR has played a crucial role in providing humanitarian assistance to millions of refugees from neighboring Afghanistan and in delivering substantial emergency relief following the catastrophic floods of late 2022.24UHRP attempted to contact several UNHCR’s offices to clarify the mechanisms and agreements in place which enable them to work in countries that are not party to the 1951 Refugee Convention, but in an eventual standard response from a media communications office in Geneva, this and other questions for this report were unanswered. However, as previously reported by UHRP25“‘Nets Cast from the Earth to the Sky’: China’s Hunt for Pakistan’s Uyghurs,” UHRP, August 11, 2021, online. and as reflected in testimonies below, there are serious concerns about UNHCR’s ability to provide meaningful protections to Uyghur refugees in Pakistan. These concerns are largely based on the impact of China’s growing economic importance to Pakistan, which is seen by many observers as undermining any political or humanitarian will to recognize and duly protect Uyghur refugees.26See, for example: Kunwar Khuldune Shahid, “How Pakistan Is Helping China Crack Down on Uyghur Muslims,” The Diplomat, June 28, 2021, online.

Very few Uyghur refugees formally engage with the Pakistani authorities or with UNHCR in Pakistan. According to UNHCR’s statistics, there were fewer than 24 registered refugees from China under UNHCR protection in Pakistan as of September 2022. This number does not specify how many of these refugees are Uyghurs or other Turkic people who were at one time citizens of China.27“Pakistan Overview of Refugee and Asylum-Seekers Population as of September 30, 2022,” UNHCR, January 18, 2023, online. UHRP made several attempts to contact UNHCR Pakistan via its website about the precise number of registered refugees from China in Pakistan, but did not receive a reply. See appendix below. However, according to estimates based on UHRP’s conversations with community leaders and NGOs, there are thought to be around 200 at-risk Uyghurs in Pakistan.

This is not to imply that UNHCR is deliberately under-reporting figures; rather, it is a reflection of the difficulties UNHCR faces in effectively carrying out its mandate in various countries, especially those that are not party to the 1951 Refugee Convention. This is compounded by the reluctance of many refugees to submit themselves and their families to uncertain scrutiny in host countries.

It is partly in recognition of UNHCR’s difficulties in providing protections that the U.S. is intending to expand the number of entities designated by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) as competent and authorized to refer individuals to the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP).28“Report to Congress on Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2023,” United States Department of State, September 8, 2022, online. The U.S. has worked closely and effectively with UNHCR in the past and will surely continue to do so, but at a time of numerous refugee crises intensifying around the world, is now looking to other entities to provide referrals.

UNHCR Status

All but one of the Uyghur refugees interviewed for this report either currently have, or they once had, UNHCR refugee status. However, none expressed any confidence that their status protected them from refoulement to the PRC, or offered a realistic prospect of being resettled by UNHCR to a third country. The remaining interviewee, Perhat, was convinced by his circle of friends in Turkey not to contact UNHCR at all. He told UHRP that those friends who already had UNHCR status when he arrived in Turkey explained to him, “They are completely useless to us. They do nothing for us.”

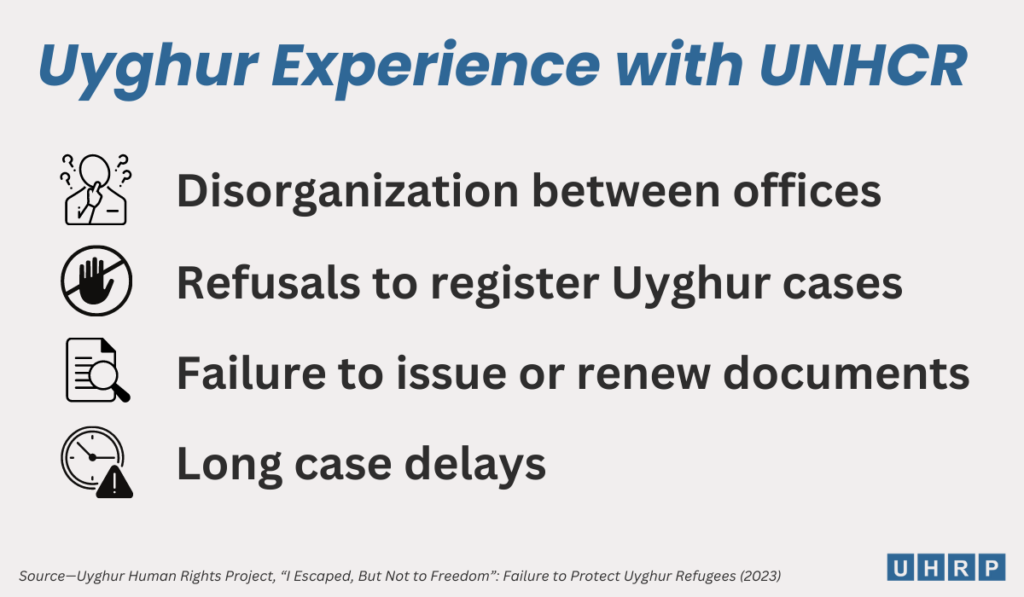

The overwhelmingly negative attitude among UHRP’s interviewees toward UNHCR is largely based on their perception that their status as a UNHCR-registered refugee serves no purpose. For example, the same interviewee who was convinced by his friends not to approach UNHCR, Perhat, repeated a belief among his associates that UNHCR in Turkey hasn’t resettled a single Uyghur to a third country since 2013.29UHRP attempted to contact various UNHCR offices to confirm this claim, but their eventual reply to this query, and other UHRP questions, was a standard paragraph on UNHCR policies via a UNHCR media and communications office in Geneva. See appendix below.

Tursun, also in Turkey, even ended up withdrawing his long-standing UNHCR refugee status in June 2022. He, his wife and four children were granted UNHCR refugee status in Turkey in early 2017, but he told UHRP, “I waited four and a half years for something to happen with UNHCR, and when nothing did, I decided to withdraw my application.” His decision to apply instead for permanent residency in Turkey was primarily spurred by his two oldest daughters being offered places at university, which as refugees with temporary residency, they weren’t eligible to accept.

Tahir also withdrew his UNHCR status, although his decision was not entirely voluntary. He arrived in Turkey with his son in 2014 to visit his daughter, who had just given birth to his first grandchild. Tahir chose not to go back to East Turkistan when his family members all disappeared as soon as they arrived in Ürümchi in 2016 for a family wedding, including his wife, daughter, first grandchild, a second infant grandchild, and his son-in-law. He duly acquired UNHCR refugee status in 2016 and was assigned residence in a small town in western Turkey. However, he found it impossible to support himself and his son there and returned to Istanbul, where he found work as a casual laborer on construction sites. Nevertheless, every month, and at considerable cost, he still had to travel back to the small town from Istanbul to check in with the immigration authorities there, as one of the conditions for retaining his temporary residence status in Turkey.

Tahir shared the perception common among all of UHRP’s interviewees that UNHCR is not even attempting to advocate on their behalf, and that the organization is inaccessible, unresponsive, and even irrelevant to them. “UNHCR was so disappointing,” Tahir told UHRP. “Four years of traveling back and forth with no status, no right to work, nothing, if anything, having UNHCR status was an added hardship.”

Ultimately, his decision to withdraw his UNHCR status was forced upon him by Turkish immigration authorities: a business acquaintance was detained on suspicion of involvement with ISIS, and Tahir fell under suspicion by association. He was detained for 49 days and released when he was cleared of all suspicion. However, upon his release, the Turkish immigration authorities said he either had to go back to the town where he was registered in western Turkey, which he was reluctant to do, or withdraw his UNHCR status and remain in Istanbul with temporary residency, which is what he chose to do. Nevertheless, with temporary residency, he is still not legally permitted to work.

Uncertainty remains among some of UHRP’s interviewees about their legal status in Turkey and how their UNHCR status interacts with local Turkish immigration procedures. Confusion centers on which agency has jurisdiction over which areas of the interviewees’ cases. A degree of uncertainty stems from the reforms of 2018: all of UHRP’s interviewees arrived in Turkey before the reforms were finalized, and they were therefore originally assessed and registered by UNHCR. After several years of incremental changes, Turkey’s Directorate General of Migration Management (DGMM) completed the assumption of formal authority over non-Syrian refugees in September 2018, but some of UHRP’s interviewees report there is little clarity from either UNHCR or DGMM over which agency has principal authority over their cases. Also, uncertainty is caused by arbitrary decision-making on the part of DGMM officials, discussed in more detail below.

“UNHCR was so disappointing. Four years of traveling back and forth with no status, no right to work, nothing, if anything, having UNHCR status was an added hardship.”

In Pakistan, UHRP is unable to confirm which documents UNHCR issues to Uyghur refugees and under which legal or humanitarian conditions. UHRP’s interviewees were themselves vague about what documents they possessed, including their purpose and validity, saying that little if anything is ever clearly explained to them. However, it is evident from the interviews conducted for this report and in UHRP’s previous reporting on conditions for Uyghur refugees in Pakistan30“‘Nets Cast from the Earth to the Sky’: China’s Hunt for Pakistan’s Uyghurs,” UHRP, August 11, 2021, online. that UNHCR’s systems are at best opaque, as well as highly unreliable and inconsistent.

One interviewee in Pakistan is a formally registered UNHCR refugee, while the remaining three have been unable to acquire or renew UNHCR papers documenting their refugee status. As they also do not have permission from the Pakistani authorities to be in Pakistan, these three people are effectively stateless and therefore in serious peril of refoulement, in addition to having no legal means of supporting themselves and their families.

The experiences of UHRP’s sole interviewee in India, Aydin, sum up some of the broader experiences of the other interviewees in this report: as a refugee in India, as in most other countries around the world, Aydin is only granted temporary residential status and as such, he is not entitled to work and cannot therefore legally support himself. Having once run his own clothing business in East Turkistan, he is forced to find work on the casual labor market in Delhi, which is rarely reliable and offers no hope of advancement. Insecure employment places him in legal jeopardy, which he fears could lead to his deportation to the PRC.

Aydin has been a UNHCR-registered refugee for over ten years since he first arrived in Nepal from East Turkistan in 2001, which is the longest period of all the interviewees. His sense of limbo is felt by other interviewees: they are condemned to a life of semi-legal subsistence in their host countries, and their interactions with UNHCR are at best an added frustration rather than a source of hope. When describing his sense of helplessness, Aydin in Delhi said, “I can’t do anything. I can’t live with UNHCR, and I can’t die with UNHCR.”

Interactions with UNHCR

The only interviewee to have a favorable impression of UNHCR is Turghun in Pakistan. Soon after he was registered as a refugee in 2018, UNHCR issued him with a permit which authorizes him to legally work. “It’s like a passport,” he explained. “And if I got into trouble with the police, there’s a number on it I can use to call UNHCR.” He reports that this permit needs to be periodically renewed, but that aside from one occasion when the renewal process took a little over a month to complete, he otherwise reports no problems in his dealings with UNHCR.

Turghun’s positive experiences with UNHCR’s offices in Islamabad are in stark contrast to all the other interviewees’ accounts.

[Uyghurs] are condemned to a life of semi-legal subsistence in their host countries, and their interactions with UNHCR are at best an added frustration rather than a source of hope.

Generally, there is deep frustration about engagement with UNHCR at even the most basic level. In 2021, UHRP reported on difficulties encountered by Uyghur refugees dealing with UNHCR in Pakistan, including perceptions that the office in Islamabad is denying services to Uyghur refugees.31Ibid. Conversations with the small sample of Uyghur refugees in Pakistan who spoke to UHRP for this report included impressions that UNHCR staff at the offices in Lahore, Rawalpindi and Islamabad are exceptionally rude and dismissive. These behaviors extended not just to Uyghurs, but also to Afghans, who are by far the largest refugee population in Pakistan. Memet, who left East Turkistan in 2006 on a passport and visa to further his religious studies in Pakistan, reports that he was shooed away from the office in Lahore. “They treat you like a beggar,” he said of the staff there.

Three of the four interviewees in Pakistan had reason to question the basic competence of UNHCR staff. Individuals specifically complained about being sent from office to office, from Islamabad to Lahore, for example, with considerable travel costs, only to find that the Lahore office wasn’t staffed at the time, or that services were actually not accessible in Lahore, even though the Islamabad office had assured that they were available. Memet told UHRP, “Neither office has a clue what the other office is doing; the Lahore office is worse in terms of staff being rude and their disorganization. The Islamabad office is almost as bad.”

As reported by UHRP in 2021, Umer Khan, who works for an organization in Pakistan assisting Uyghurs fleeing East Turkistan, said he had helped at least 37 Uyghur families escape into Pakistan and from there to Turkey. “The UNHCR isn’t helping these people, and whenever I take them to the main office in Islamabad, the staff are hostile and refuse to register Uyghur cases,” he said.32Ibid.

Abdullah described how in 2017 UNHCR Pakistan called him in for an interview as part of his Refugee Status Determination process. UNHCR staff told him that he would be interviewed again some 60 to 70 days later as a continuation of that same process. However, as of November 2022, over five years later, he is yet to hear from them again and has been unable to contact anyone in UNHCR’s offices to assist him on the several times he’s called. He explained that he was issued with a “UNHCR card” at his initial interview in 2017 identifying him as a refugee, probably a Proof of Registration card,33A Proof of Registration (PoR) card is issued to people who have been registered with UNHCR as refugees in Pakistan and is intended as an identity card and part of the legal basis for refugees to remain in Pakistan. See UNHCR info online. but UNHCR in Islamabad refused to renew it once it expired.

As of November 2022, Ablimit, who left East Turkistan with his family when he was two years old, had no documentation from either UNHCR or the Pakistani authorities permitting him to be in Pakistan. “You can’t speak to UNHCR unless they want to speak to you,” he told UHRP. He added that he tried to speak to someone in person there “around a year ago,” but that they were “zero help” and wouldn’t provide him with any documentation.

There is deep frustration about engagement with UNHCR at even the most basic level.

The interviewees’ experiences of UNHCR failing to issue or to renew documents identifying people as refugees is extremely troubling in the wake of a February 2023 report that Pakistani police and intelligence officials threatened several Uyghur families with deportation unless they had valid UNHCR documents. One of the families told Radio Free Asia (RFA) that they had tried “three or four times” to renew their documents, but were told by UNHCR staff that documents were no longer being issued, and that the office would call them when they were available again. RFA and several other organizations contacted a UNHCR official in Geneva to inquire about this apparent suspension of services. The official said she would call the office in Pakistan, and two days later, the Uyghur families were duly called into UNHCR’s office and finally issued with the documents they needed to allay the immediate threat of deportation.34Erkin, “Pakistan threatens to send Uyghur refugee families back to China,” Radio Free Asia (RFA), February 23, 2023, online.

A database maintained by the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs records the deportation of 15 Uyghur refugees from Pakistan to the PRC between 2002 and 2023.35The Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs, “Transnational Repression” database, available online. An earlier case of group deportation was a death sentence. In the wake of the Ghulja Massacre in 1997, Pakistan deported 14 Uyghurs, whom the Chinese authorities summarily executed.36“No Space Left to Run: China’s Transnational Repression of Uyghurs,” UHRP, June 24, 2021, online.

Beyond the threat of formal refoulement, a further key detail to understanding the plight of Uyghurs in Pakistan is the persistence of rumors that Pakistani police and other officials, as well as UNHCR staff, are willing to hand Uyghur refugees over to the Chinese authorities in return for illicit payment. UHRP has obtained no evidence to substantiate such rumors, and the point of repeating them here is not to lend them credence but to document the profound mistrust that many Uyghurs in Pakistan feel towards Pakistani and UNHCR officials. Memet related a rumor he had heard that the Chinese authorities pay Pakistani UNHCR staff for information identifying and locating Uyghurs in Pakistan. Abdullah reported he had heard rumors that the Chinese government pays Pakistani police officials US $50,000 for each deported Uyghur. The prevalence of these rumors, unsubstantiated by concrete evidence, is a stark indicator that the interviewees harbor deep mistrust due to the vulnerability of their situation in Pakistan.

Perhat in Turkey, who was persuaded by friends to avoid the trouble of registering with UNHCR altogether, still sees no value in registering with UNHCR even after spending six months in immigration detention in 2017. A published poet and essayist who first arrived in Turkey in 2013, Perhat relied on casual work in restaurants and construction sites to survive while also volunteering with Uyghur community groups until he was offered the chance to pursue a Master’s degree at a local university. But the temporary residency that his status as a student confers doesn’t extend beyond the end of his studies. Therefore, he faces the prospect of again living in hiding in Turkey under the threat of deportation. With such uncertainty, he told UHRP it might be preferable “to die a proud Uyghur martyr in a Chinese prison” than to live in constant fear.

“You can’t speak to UNHCR unless they want to speak to you,” [Ablimit] told UHRP. He added that he tried to speak to someone in person there “around a year ago,” but that they were “zero help” and wouldn’t provide him with any documentation.

A common complaint from UHRP’s interviewees in Turkey is that contacting UNHCR for any reason is next to impossible. Interviewees report that threats and harassment from Chinese officials or their proxies, what is defined as transnational repression, are profoundly distressing, but UNHCR is perceived by the interviewees to be dismissive of their fears. Elyar, who left East Turkistan in 2015 with a passport and visa to escort his son to Malaysia for study, has faced a near constant barrage of threats and harassment from Chinese officials ever since his departure. He began receiving calls from Chinese officials in East Turkistan soon after arriving in Turkey, threatening retaliation against members of his and his wife’s families in East Turkistan if he didn’t return. But the frequency and intensity of the calls increased when Elyar became a politically active member of the Uyghur community.

He reports that he even had to confront two men he saw approaching his home as he returned from an errand while his children were alone inside. He reports the men said, “We’re only doing our duty,” before leaving the area, which he interpreted as an admission that they were acting on the orders of people linked to the Chinese authorities. He explained that his wife is also regularly followed by unidentified individuals.

The Turkish police took the harassment seriously enough to enable Elyar and his family to relocate to a different city; however, he said he was unable to get through to anyone at UNHCR to update them on the urgency of his case. “There are just no channels to tell them anything,” he told UHRP.

Arslan, who fled East Turkistan in 2014 after questioning the circumstances of his brother’s unexplained death in hospital, recounted that the Turkish authorities offered him relocation within Turkey because of ongoing Chinese state transnational repression, but he reluctantly declined the offer due to the upheaval of moving to a new and unfamiliar city. In brief communications, UNHCR advised him only to “avoid crowded places.”

“I escaped, but not to freedom. It’s the same stresses, the same uncertainty, the same restrictions.”

Iskandar, who left the PRC in 2014 having faced harassment due to his father’s escape from East Turkistan in 2002, has persistently encountered Chinese state transnational repression. He told UHRP, “I never feel safe. It’s like being back in East Turkistan. Even in high school the pressures made me consider suicide, but then with the notion of escaping I started to have hope. And I escaped, but not to freedom. It’s the same stresses, the same uncertainty, the same restrictions.” He added that UNHCR merely tells him to report the harassment to the Turkish police, and the Turkish police tell him to report it to UNHCR.

Interactions with Turkish Immigration Authorities

Turkey is host to the world’s largest population of refugees: around 3.6 million people fleeing the civil war in neighboring Syria, and an approximate 325,000 from elsewhere, predominantly Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan.37“Turkey Policy Brief,” International Center for Migration Policy Development, January 2021, online. Among the refugee population in Turkey are an estimated 10,000 Uyghur refugees within a total of approximately 50,000 Uyghurs living in Turkey.

Turkey has historically been supportive of the Uyghur people, based not just on its value of humanitarian hospitality to refugees, but also to a large degree on the strong affinities binding Turkish and Uyghur culture.38See, for example, Mettursun Beydulla, “Experiences of Uyghur Migration to Turkey and the United States: Issues of Religion, Law, Society, Residence, and Citizenship,” in Migration and Islamic Ethics: Issues of Residence, Naturalization and Citizenship (Brill, 2020), pp. 174-195, online.

Nevertheless, expanding economic ties between Ankara and Beijing are shifting Turkey’s priorities with regard to Uyghur refugees. As a consequence, there is a sense among UHRP’s interviewees that Uyghur refugees are becoming less and less welcome in Turkey. The importance of growing commercial ties between Turkey and China39Trade volume between the two countries grew from US $27.27 billion in 2015 to US $35.9 billion in 2021. See: “Türkiye-People’s Republic of China Economic and Trade Relations,” Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Foreign Affairs, undated, online. has potentially contributed to the decisions that led to several Uyghurs being deported in recent years to a third country initially, such as Tajikistan, from where it is feared they have been escorted by Chinese police back to the PRC.40“No Space Left to Run: China’s Transnational Repression of Uyghurs,” UHRP, June 24, 2021, online. (See also: “China’s enticements to second countries to forgo due process: Cambodia and Thailand” below.) To date, no Uyghurs have been deported directly from Turkey to China. However, in 2017, Turkey signed a bilateral extradition agreement with China which Beijing has already ratified but the Turkish parliament has so far refrained from doing so in the face of popular protest.41Bradley Jardine, “Great Wall of Steel: China’s Global Campaign to Suppress the Uyghurs,” The Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars, March 2022, online. Indeed, warmer official bilateral ties and any increasing inclination to defer to Beijing’s demands regarding Uyghurs is not necessarily reflected in popular sentiment. In multiple surveys over the decades, more than half of Turkish people have expressed negative or critical attitudes of China, largely a reflection of widespread sympathy for the plight of Uyghurs, and a poll from 2022 showed only 27 percent have a positive view of China.42James M. Dorsey, “Challenging China: Turkey walks a fine line on repressed Uighurs,” The Times of Israel, January 4, 2023, online.

There is a sense among UHRP’s interviewees that Uyghur refugees are becoming less and less welcome in Turkey.

Prior to 2018, UNHCR worked closely with the Turkish immigration authorities in determining the status of refugees arriving in Turkey. However, in September 2018, the Turkish authorities assumed full control over the determination process, one of around 30 countries to have done so between 1998 and 2018.43Caroline Nalule, Derya Ozkul, “Exploring RSD handover from UNHCR to States,” Forced Migration Review, 65 (November 2020), 27–29, online. UNHCR still provides advisory and counseling services to non-Syrian refugees44“Registration and RSD with UNHCR,” UNHCR Türkiye, accessed on January 31, 2023, online. and provides RSD training to Turkish officials45Caroline Nalule, Derya Ozkul, “Exploring RSD handover from UNHCR to States,” Forced Migration Review, 65 (November 2020), 27–29. in addition to attempting to facilitate permanent resettlement in third countries.

Several, but not all, of the interviewees in Turkey say that they have encountered a culture of hostility among Turkish immigration officials towards Uyghur refugees holding UNHCR status. Historically, Turkey has seen itself as the dominant pole in Turkic culture across Central Asia including East Turkistan. Turkish people often refer to Uyghurs as “Uyghur Turks,” indicating a widespread feeling of close ethnic kinship.46See, for example, Shannon Tiezzi, “Why Is Turkey Breaking Its Silence on China’s Uyghurs?” The Diplomat, February 12, 2019, online. Some of UHRP’s interviewees confirm that many in Turkey feel that everyone from a Turkic background is expected to have an allegiance to Turkey. Turning to non-Turkic sources of aid (including international agencies like UNHCR) can be regarded in Turkish nationalist ideology as a snub. This is not to claim that Uyghurs are specifically targeted with this hostility purely because they are Uyghurs, and neither is it to claim that this hostility is policy-led. Rather, this hostility is perceived to come from subjective attitudes within Turkish government agencies with which Uyghur refugees need to interact. For example, Iskandar reports that when he approached Turkish immigration officials in 2015, he was told by the official in charge of his case to withdraw his application to UNHCR or face being assigned residency in an area of Turkey that at the time was the scene of fighting between Kurdish and ISIS forces. He declined and went into hiding for a couple of years.

A Turkish immigration official told Tahir that even though Tahir had withdrawn his application with UNHCR in exchange for permission to remain in Istanbul, the mere fact he had applied to UNHCR in the first place led Turkish immigration officials to regard him as “untrustworthy.” Tahir claims he is now barred from applying for permanent settled status in Turkey. Instead, he has to apply for a rolling two-year temporary residential status with no certainty of approval when it is time to renew.

Arslan knows he is ineligible to apply for permanent residential status in Turkey because he holds UNHCR refugee status, but he is too fearful of the uncertainties of what may happen to him if he does withdraw his UNHCR status.

In February 2021, Turkish immigration authorities told Elyar that a third country would be willing to resettle him and his family. “But when I went to the office, I was told there was no offer, and they’d only called me in to tell me that because I’d applied for UNHCR status, Turkey didn’t want me, and that my children and I would never be offered refugee status in Turkey, not to mention Turkish citizenship; and in fact, all Uyghurs should leave Turkey, they said. Even if I withdrew my UNHCR application, I would still never be offered residency or citizenship in Turkey.”

The Uyghur refugee interviewees in Turkey are deeply frustrated at the limbo in which they find themselves. They are unable to find permanent resettlement through UNHCR, but powerless to legally provide for themselves. As Arslan explained, “We don’t need handouts from UNHCR. All we want is the chance to work to support ourselves. We’re able, we’re trained, we’re smart, with languages and computer skills, but we can do nothing for ourselves. We don’t want handouts, but there’s nothing else for us.”

Family Members in East Turkistan

Although UHRP’s interviewees all fled East Turkistan prior to 2016, they are still impacted in their host countries by current atrocities through the treatment of their families still in East Turkistan and by China’s transnational repression.47Bradley Jardine, Natalie Hall, and Louisa Greve, “‘On the Fringe of Society’: Humanitarian Needs of the At-Risk Uyghur Diaspora,” UHRP, February 1, 2023, online. The fate of their family members, friends, and acquaintances in East Turkistan are a distressing reminder of what would await them if they were refouled.

Every single one of UHRP’s interviewees describe that they have friends and relatives who have been interned in concentration camps in East Turkistan. Tahir’s wife, daughter, and son-in-law were sent to concentration camps upon flying to Ürümchi from Turkey in 2016, coming under suspicion because they had spent time in Turkey. His two young grandchildren, one of them still nursing, were put into the care of their paternal grandfather, whose own wife, as well as another son, were interned in a camp. Tahir said his wife was released after spending four years in a concentration camp and his daughter a year and a half, during which time he received no reliable information on them or their welfare; the whereabouts of his son-in-law are still unknown at the time of reporting, some six years later.

Every single one of UHRP’s interviewees describe that they have friends and relatives who have been interned in concentration camps in East Turkistan.

Tursun reports that his wife’s father was sent to a concentration camp for four years and one of his wife’s sisters for three years having come under suspicion for attending their local mosque. “They’re not extremist or radical or anything, they just went there to pray,” he told UHRP.

Arslan reports that 33 members of his extended family, including his mother, a surviving brother, and an uncle, either are or have been detained in concentration camps.

Several of UHRP’s interviewees spoke about how their decision to flee has placed additional pressures on their family members in East Turkistan. They expressed fears over increased levels of surveillance and harassment, as well as the likelihood that loved ones may be interned in a concentration camp or imprisoned in direct retaliation for the decision to seek refuge overseas.

Perhat fled East Turkistan in 2013 with the intention of his wife and five children joining him once he was settled outside of China. However, in 2015, he heard his wife had been arrested. Unable to find any reliable information about her or their children, he became active in the Uyghur protest movement in Turkey. The Chinese police frequently called him and made threats in an attempt to stop his protests, and in April 2022, police in Kashgar contacted him via WeChat. The police put his 80-year-old father and a brother in front of a camera. Both had recently been released from a concentration camp, and Perhat described them as “skeletal.” He learned on this call that his wife had been sentenced to 10 years imprisonment in 2015, but he wasn’t told what the charges were against her. He also learned for the first time that one of his children had been killed several years earlier in a traffic accident. Perhat said the officers offered him money for his family if he would stop protesting, but he refused. He added, as of September 2022, he hasn’t answered his phone on any of the dozen or so times the police have called.

“When I speak to my 81-year-old father, it’s only to say ‘We’re good’ and for him to say ‘I’m good.’ I’m too afraid to be in touch with other relatives and they’re too afraid to be in touch with me.”

Tursun in Turkey explained he’s rarely in touch with family out of fear for their safety. “When I speak to my 81-year-old father, it’s only to say ‘We’re good’ and for him to say ‘I’m good.’ I’m too afraid to be in touch with other relatives and they’re too afraid to be in touch with me.”

Arslan described that soon after he fled East Turkistan in 2016 police called him urging his return. The police called back two weeks later saying they had detained and beaten his surviving brother, suspecting him of helping Arslan to escape. The police threatened to further detain his parents and other family members.

Aydin in India deliberately stopped contacting his family in 2017, aware of the risks to them of being in touch with him.

Memet related the internment of his mother in 2017 soon after her return to East Turkistan from visiting him in Pakistan. She was interned for three years, during which time her weight dropped from 100 kg to 50 kg (220 lb. to 110 lb.).

Concern for the fate of family members left behind in East Turkistan is possibly the greatest psychological burden endured by Uyghur refugees. Mehmet Tohti, founder and Executive Director of the Uyghur Rights Advocacy Project (URAP) in Canada, said of Uyghur refugees in his community: “You remember the pain every time you sit at a table alone and think of the loved ones who aren’t there. I haven’t seen my family for over 31 years. It’s a lifelong punishment from the Chinese state. Whoever you talk with, they all share remarkably common experiences wherever they reside. Not knowing the whereabouts or condition of loved ones is a constant torment.”48Ibid.

“The last time I called them they told me not to call. And we said we would just pray for each other instead.”

Abdullah in Pakistan said he hasn’t been in touch with his family since 2014. “The last time I called them they told me not to call,” he said. “And we said we would just pray for each other instead.”49UHRP in collaboration with the Oxus Society for Central Asia has published five reports so far detailing the Chinese authorities’ systematic efforts to harass and intimidate Uyghurs abroad. For these reports and other materials on the transnational repression of Uyghurs, see UHRP’s online archive. See also: David Tobin & Nyrola Elimä, “‘We know you better than you know yourself’: China’s transnational repression of the Uyghur diaspora,” The University of Sheffield, April 2023, online.

V. China and UNHCR

China appears to have a very uneasy relationship with UNHCR. Although the agency has a staff presence within China’s UN offices in Beijing, the Chinese authorities nevertheless forbid UNHCR and other non-state or non-approved actors from carrying out humanitarian work on behalf of refugees crossing into the PRC and reportedly refuse to cooperate with UNHCR’s processing of asylees within the country50Jonathan Lesh, “To Be a Global Leader, China Needs a New Refugee Policy,” The Diplomat, July 21, 2017, online. Therefore, despite the PRC bordering several countries from which refugees continue to flee, including Myanmar and North Korea, UNHCR formally recognized only 313 people in all of mainland China as refugees in 2021,51See: UNHCR, “People’s Republic of China,” Factsheet, January 2021, online. plus another 800 or so defined as “persons of concern,” most of whom reportedly flew in with passports and visas and then claimed asylum.52According to UNHCR, around 300,000 ethnically Chinese refugees from Indochina have been in China’s southern provinces since the late 1970s; although unlikely to be in any danger of refoulement, they are yet to be “de facto integrated pending Government regularization.” See: UNHCR, “China,” accessed January 27, 2023, online.

The PRC does not provide significant assistance to UNHCR in terms of resources for humanitarian work elsewhere in the world. In 2016, at the height of the Syrian refugee crisis, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs claimed the country was providing monetary aid “compatible with [its] abilities,” but according to the UN’s Financial Tracking Service, China donated just US $3 million in 2016, which was the same amount donated by Hungary.53Jonathan Lesh, “To Be a Global Leader, China Needs a New Refugee Policy,” The Diplomat, July 21, 2017, online.

Leaked information from a police database in Ürümchi shows that Uyghurs who apply for refugee status abroad are automatically labeled as “terrorist” on their police files.

Closer Chinese engagement with UNHCR and its mandate would not only entail closer scrutiny of China’s treatment of refugees within its own borders, the plight of up to 60,000 North Koreans, for example,54Jeong Eun Lee, “UN asks China not to send 7 North Korean refugees back home,” Radio Free Asia, March 15, 2022, online. but would also expose China to more systematic scrutiny of the ordeals faced by the growing numbers of Uyghurs and other PRC nationals fleeing persecution. It should not be overlooked that since the start of Xi Jinping’s presidency, the number of PRC nationals, not just Uyghurs, claiming asylum abroad each year increased from 15,362 in 2012 to 107,864 in 2020, comprising a cumulative total of around 613,000 people,55“Under Xi Jinping, the number of Chinese asylum-seekers has shot up,” The Economist, July 28, 2021, online. numbers that could plausibly compare with those from a war-zone elsewhere in the world.

As a permanent member of the UN Security Council, the PRC is unlikely to express formal opposition to UNHCR’s mandate or its modus operandi. But far from supporting its mandate, the Chinese authorities not only thwart UNHCR’s work within the PRC, they also actively seek to bypass UNHCR’s role in recognizing PRC-national refugees abroad, insisting instead that any such people are first and foremost criminals. Indeed, leaked information from a police database in Ürümchi shows that Uyghurs who apply for refugee status abroad are automatically labeled as “terrorist” on their police files.56Yael Grauer, “Revealed: Massive China Police Database,” The Intercept, January 29, 2021, online.

In its efforts to bypass international institutions and procedures intended to assess an individual’s refugee status, Beijing has instead brokered close to 60 bilateral agreements with second countries which include provisions for extraditions.57Jerome A. Cohen, “Should Murder Go Unpunished? China and Extradition, Part 1,” The Diplomat, June 23, 2021, online. The Chinese authorities then cite these agreements as the normative legal basis for seeking the extradition of Uyghur refugees to the PRC.

Subversion of International Refugee Protection Standards: Shaheer Ali

The case of Shaheer Ali was among the first in which the Chinese authorities invoked the post-9/11 threat of terrorism to tarnish peaceful political opposition in East Turkistan. As noted above, automatically labeling Uyghurs who claim refugee status abroad as “terrorist” now appears to be standard practice by the Chinese security apparatus. Shaheer Ali’s case was also one of the first to demonstrate Beijing’s willingness and ability to undermine UNHCR’s mandate as a means of pursuing political agendas in East Turkistan.

Shaheer Ali had been granted refugee status by UNHCR in 2001 in Nepal having fled the year before, according to one account by hiding in the hold of a fuel truck passing through Tibet, and was awaiting re-settlement through UNHCR to a third country.

Aydin in India reports that he spent several months in Nepali immigration detention in the company of Shaheer Ali, and that it was Shaheer Ali who persuaded him to apply for UNHCR refugee status.

Shaheer Ali had already spent time in detention in East Turkistan in the 1990s for his associations with an underground political and religious reform party. In recorded testimony acquired by RFA, during an eight-month period of detention Shaheer Ali suffered regular and prolonged torture by his captors to make him confess to accusations of “separatism.”

Shaheer Ali’s case was also one of the first to demonstrate Beijing’s willingness and ability to undermine UNHCR’s mandate as a means of pursuing political agendas in East Turkistan.

In December 2001 Nepalese immigration authorities took Shaheer Ali into detention on the strength of Chinese assertions that he was a “terrorist.” Aydin reports, “One night, a car came from the Chinese embassy and took away Shaheer Ali and three other people he’d been detained with.” Aydin added, “A Nepali woman from UNHCR came to see us and asked us about Shaheer Ali, but she had no idea they’d been taken away by the Chinese, and she immediately left.”

Despite his status as a UNHCR-recognized refugee, Shaheer Ali was deported to China in January 2002, tried in secret on a variety of weapons charges and another charge that he led “a number” of terrorist organizations. China executed him in March 2003. The Chinese authorities confirmed Shaheer Ali’s execution in a media report of his trial, but not when or where his trial and execution took place.58“Executed Uyghur refugee left behind tapes detailing Chinese torture,” Radio Free Asia, October 23, 2003, online; and “China: Further information on Fear of forcible return,” Amnesty International, October 24, 2003, online. None of the evidence used to convict him was ever made public.

More than 20 years after Shaheer Ali was refouled to China and 20 years since his execution, there are no signs that UNHCR is any better able to protect Uyghur refugees against China’s violations of international law.

Interference in UNHCR Procedures and Misuse of Interpol: Ershidin Israil

Another alarming case of UNHCR’s inability to provide adequate protection to Uyghur refugees is that of Ershidin Israil. A teacher from Ghulja, Ershidin Israil fled the Uyghur Region on foot into Kazakhstan in September 2009, fearing arrest after speaking to RFA about the death in custody of Shohret Tursun, a witness to the July 5 massacre earlier that year.

Ershidin Israil had already served a seven-year prison sentence beginning in the late 1990s on a charge of “separatism,” an extremely vague and catch-all charge routinely used to criminalize Uyghurs.59See, for example, Lindsay Maizland, “China’s Repression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang,” Council on Foreign Relations, September 22, 2022, online. Ershidin Israil’s status as a former political prisoner and known “activist” in touch with RFA would certainly have placed him under intense scrutiny by the Chinese security apparatus.

Soon after arriving in the Kazakh capital of Almaty in September 2009, Ershidin Israil approached UNHCR’s offices, and in March 2010, he was granted refugee status and offered resettlement in Sweden.

However, the Chinese authorities interfered in proceedings as Kazakh authorities prepared the necessary documents for Erhsiden Israil to leave Kazakhstan for Sweden. Once the Kazakh authorities learned from UNHCR of Ershidin Israil’s identity and status within the country, the Chinese authorities also soon came by this information either by formal or informal means.

The Kazakh authorities refused to provide Ershidin Israil with an exit visa, and on April 3, 2010, two days after he was supposed to have left for Sweden, placed him under house arrest.

At this point, it is unclear whether the Kazakh authorities were made aware of an existing Interpol order calling for Ershidin Israil to be detained on allegations of terrorism, or whether the Chinese authorities simply retroactively requested the order via Interpol, known as a red notice, as a more “legitimate” means of ensuring his extradition. However, the allegation of terrorism against Ershidin Israil did not exist while he was still in East Turkistan and before he spoke to RFA about the death in police custody of Shohret Tursun.60“SCO Member State Kazakhstan’s Return of Uyghur Refugee to China Demonstrates Disregard of International Human Rights Obligations,” Human Rights in China, June 1, 2011, online.

Nevertheless, in June 2010, Kazakhstan arrested Ershidin Israil in Almaty on the strength of the red notice.61“Deported Uyghur Faces Terrorism Charges,” Radio Free Asia, June 14, 2011, online.

Then on May 3, 2011, UNHCR annulled his refugee status. Without providing any details, a senior UNHCR official said, “We reviewed his case based on new information,” adding, “Had we had access to that information earlier, we would not have given him [refugee] status.”62Hanna Beech, “China’s Uighur Problem: One Man’s Ordeal Echoes the Plight of a People,” Time, July 28, 2011, online. It can be reasonably speculated that the “new information” was the Interpol red notice.

Interpol Red Notices

The Chinese authorities have used the expedient of Interpol red notices on numerous occasions in recent years. For example, in 1997, Interpol issued a red notice “wanted” alert for Dolkun Isa, then a leader of the Munich-based World Uyghur Youth Congress. Despite Dolkun Isa’s high profile as a campaigner for Uyghur rights, the red notice succeeded in interfering with his campaigning in numerous democratic countries, including visa denials, canceled visas, denial of entry, and police interrogations. When entering South Korea to attend a human rights conference in 2009, he came close to being deported to China. After international NGOs worked on his case for several years, the red notice was finally canceled in 2018.

Similarly, in late 2021, an Interpol red notice was used to secure the extradition of Idris Hasan to the PRC from Morocco, alleging his membership of a terrorist organization. However, once made aware of Idris Hasan’s years of work as a human rights defender in Turkey, Interpol suspended his red notice. At the time of this report’s publication, however, he remains in detention in Morocco and at risk of refoulement.

A major flaw in the Kazakh authorities’ case against Ershidin Israil soon became apparent: the reason given to UNHCR for refusing to allow him to travel was that he was suspected of espionage on behalf of the Chinese government; but the reason given to the E.U. was that he was suspected of committing terrorist acts in the PRC. UNHCR was reportedly aware of this major inconsistency, which should have been revealing of dishonesty or at least incompetence on the part of the Kazakh authorities. This lack of consistency should have raised serious concerns about the validity of the entire case against Ershidin Israil.

Nevertheless, after a year in detention, Kazakhstan deported Ershidin Israil to the PRC on May 30, 2011. Since then, aside from confirmation during a routine Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs press conference that he was to be tried on charges of terrorism, no information on Ershidin Israil’s status or condition has been made publicly available.

Undoubtedly, the actions of the Kazakh authorities were the key factor in Ershidin Israil’s refoulement, along with the Chinese authorities’ appropriation and abuse of Interpol’s red notice system.

But in addition, Ershidin Israil’s case poses serious questions about the ability of UNHCR to fulfill its mandate in the face of egregious interference by the Chinese authorities. China’s political and economic power, both bilaterally and within global and regional organizations, leaves countries susceptible to pressure from Beijing.

The bald-faced actions of local authorities in Nepal and Kazakhstan resulted in refoulement of individuals who were, or should have been, under UNHCR protection. Their execution and disappearance, respectively, raises serious alarm about the integrity of the international refugee protection regime.

Enticements to Second Countries to Forgo Due Process: Cambodia and Thailand

In several cases, the Chinese authorities have used economic enticements to secure the forcible return of Uyghur refugees from second countries, encouraging those countries to bypass UNHCR involvement and other forms of international oversight. Two of the most flagrant cases of mass refoulement are those of the 22 Uyghurs deported from Cambodia in 2009, and the 109 Uyghurs deported from Thailand in 2015, in a case that continues to cause deep concerns for the welfare of approximately 50 Uyghurs still in Thai immigration detention since 2014.

The 22 Uyghurs in Cambodia, including children and a pregnant woman, arrived in Phnom Penh individually and in groups in the weeks and months following the July 5, 2009 unrest in Ürümchi.63“Uyghur Asylum Bid in Cambodia,” Radio Free Asia, December 3, 2009, online. Sar Kheng, Minister of the Interior and Deputy Prime Minister, provided assurances to the U.S. Embassy in Phnom Penh that the Uyghur refugees’ cases would be routinely processed by UNHCR in cooperation with Cambodian officials. However, Sar Kheng also told UNHCR officials that Cambodia “was in a difficult position due to outside forces,”64“Cambodia’s Uighur ‘Madness’,” The Diplomat, July 19, 2011, online. no doubt because of an imminent visit to Cambodia by then Chinese vice president Xi Jinping.

Ershidin Israil’s case poses serious questions about the ability of UNHCR to fulfill its mandate in the face of egregious interference by the Chinese authorities.

On December 17, 2009, the same day Sar Kheng had given his assurances to the U.S. ambassador, Cambodian authorities unilaterally changed the established protocols for assessing refugee claims by formally excluding UNHCR from the Refugee Status Determination process65Ibid. and authorized the mass deportation of the 22 Uyghurs to China. They were placed on board a plane bound for Shanghai on December 19, two days before Xi Jinping’s arrival.

Upon Xi’s arrival, the Cambodian government signed loan deals and investment agreements with the Chinese government with an estimated value to Cambodia of US $1.2 billion.66Seth Mydans, “After Expelling Uighurs, Cambodia Approves Chinese Investments,” The New York Times, December 21, 2009, online. China publicly thanked Cambodia for returning the Uyghurs.67“China thanks Cambodia for deported Uighurs,” Associated Press, December 21, 2009, online.

Thailand is not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention and therefore under no treaty obligation to coordinate its domestic refugee policies and practices with UNHCR. However, Thailand is nonetheless obligated to provide protection to refugees under other conventions and treaties to which it is a party, such as the UN Convention Against Torture, which bars governments from forcibly returning individuals to countries where there is reason to believe they will be tortured or otherwise treated inhumanely.68“Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment,” United Nations OHCHR, December 10, 1984, Article 3, online.

As of 2014, Thailand was along a commonly-used route for Uyghur refugees traveling on foot towards Malaysia, from where they would travel on to Turkey. In early 2014, Thai immigration authorities discovered around 350 Uyghur refugees hiding on a rubber plantation close to the border with Malaysia. All were placed in immigration detention, and whatever attempts were made by UNHCR to determine the Uyghurs’ refugee status at that time were unsuccessful.

Many of the 350 Uyghurs refused to talk to Thai immigration officials, fearful they would be summarily deported to the PRC, and similarly, they refused to talk to Chinese embassy personnel dispatched to interrogate them.69Luke Hunt, “Uyghurs Test ASEAN’s Refugee Credentials,” The Diplomat, March 19, 2014, online.

The Thai government, placed in power by a military coup in May 2014 soon after the detention of the 350 Uyghurs, nevertheless allowed around 173 of the Uyghurs, mostly women and children, to depart Thailand on flights to Turkey, arriving on June 30, 2015.

But on July 9, 2015, Thai authorities returned 109 of the remaining Uyghur refugees on two flights to China. Each refugee was forced to wear a numbered bib and flanked by two uniformed Chinese police officers. The head of each Uyghur was covered with a black hood.70Thanyarat Doksone, “Thailand condemned for repatriation of 109 Uighurs to China,” Associated Press, July 9, 2015, online.

As noted above, official documents leaked in 2019 indicate that Uyghurs who claim refugee status abroad are labeled as “terrorists” on their police record.71Yael Grauer, “Revealed: Massive China Police Database,” The Intercept, January 29, 2021, online. Tong Bishan, an official with China’s Ministry of Public Security claimed a few days later in Chinese state media that “most” of the 109 were on route to participate in “jihad” in Syria and Iraq, “a dozen” were involved in terrorism in East Turkistan, and money that some of the 109 had paid to human traffickers ended up in accounts owned by the “East Turkistan Islamic Movement.” He added that if they had arrived in Turkey, some among the 109 would have been vulnerable to recruitment by terrorist organizations. “They are under-educated, and it is difficult for them to make a living abroad,” he explained.72“China dismisses claims that Uyghur deportees face unfair treatment: report,” Global Times, July 14, 2015, online.

Reports about the deportation noted that the Thai military had recently agreed to purchase three Chinese submarines at a reported cost of US $1 billion, a transaction in which the deportation of the 109 Uyghurs almost certainly factored.73See for example: Catherine Putz, “Thailand Deports 100 Uyghurs to China,” The Diplomat, July 11, 2015, online.

UNHCR was unusually forthright in its condemnation of the Thai authorities, with Volker Türk, then UNHCR’s Assistant High Commissioner for Protection and now the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, describing the deportations as “a flagrant violation of international law.”74Catherine Putz, “Thailand Deports 100 Uyghurs to China,” The Diplomat, July 11, 2015, online.

The deportations immediately raised fears for the fate of the remaining Uyghur detainees from among the original 350,75Following several escape attempts, some successful and some not, as well as several deaths in detention, the current estimate for the number of Uyghurs still in detention from the approximately 60 who were detained as of 2015 is 49. now numbering around 50, but in the ensuing years there has been no substantial movement in their cases. The most likely reason is that the Thai authorities are unwilling to commit either to returning them to the PRC and facing further international condemnation, or to extending humanitarian relief to them and risking economic and political sanctions from Beijing.

The approximately 50 remaining refugees have made repeated written applications to register with UNHCR. However, as we understand it, UNHCR does not have permission from the Thai government to register Uyghur refugees in Thailand.

There are profound concerns for the welfare of the remaining refugees. In 2014, a three-year-old boy in the group died of tuberculosis having failed to respond to treatment in the overcrowded and unsanitary detention center where he and his family were being held.76“Three-Year-Old Uyghur Boy Dies in Thai Detention,” Radio Free Asia, December 24, 2014, online.

In 2018, a 27-year-old man named Bilal died of cancer in detention.77“Press release: WUC calls for the Thai government to address plight of Uyghur refugees after Uyghur man dies in custody,” World Uyghur Congress, August 3, 2018, online. In February 2023, Aziz Abdullah died from an unspecified lung infection having been ill for several weeks but denied medical treatment until he collapsed. He was 49 years old. His wife and children, who escaped East Turkistan with him in 2013, were among the 173 flown to Turkey in June 2015.78“Aziz Abdullah: Uyghur asylum-seeker death heaps pressure on Thailand,” BBC, February 20, 2023, online. And in April 2023, Mattohti Mattursun, a 40-year-old man, died the same day he was finally transferred to hospital for a suspected liver complaint having suffered for weeks without treatment for stomach pains and vomiting.79“WUC and UHRP Grieved by Death of Uyghur Refugee in Detention Center in Thailand,” UHRP, April 24, 2023, online.

China’s economic and diplomatic influence is rapidly increasing around the world and particularly among its regional neighbors, not least because of China’s Belt and Road Initiative policy, which has seen China make significant capital investments in many of those countries’ civil infrastructures. However, many of these countries are now beholden to China in what critics describe as a “debt trap,”80Lingling Wei, “China Reins In Its Belt and Road Program, $1 Trillion Later,” The Wall Street Journal, September 26, 2022, online, and Bernard Condon, “China’s loans pushing world’s poorest countries to brink of collapse,” Associated Press, May 18, 2023, online. arguably making the fate of Uyghur refugees in those countries ever more likely to be factored into negotiations in which the host countries will have little leverage to resist Beijing’s demands.

VI. Barriers to Safe Haven and Resettlement

Uyghur refugees face a uniquely hostile set of circumstances due to the aggressive nature of the Chinese authorities’ transnational repression: possibly no other refugee population is subjected to systematic cross-border pursuit, punitive threats, and harassment, and certainly not on a global scale. In addition, China’s diplomatic pressure on host countries to deport Uyghurs on demand, deliberately sidelining actors such as UNHCR, renders Uyghur refugees as potentially the world’s most at-risk refugee population in a non-militarized context.

Despite being a permanent member of the UN Security Council, China has demonstrated no compunctions in thwarting UNHCR’s mandate. In addition, UNHCR’s resources are undoubtedly stretched in countries like Turkey and Pakistan, already struggling with huge refugee populations. Some 3.6 million refugees from the civil war in neighboring Syria make Turkey host to the world’s largest refugee population, and Pakistan has at various times hosted comparable numbers of Afghan refugees, with the number currently estimated to be 1.3 million people. While there is some understanding among UHRP’s interviewees of the limits of UNHCR’s ability to facilitate safe haven and resettlement under such conditions, there is also deep frustration at UNHCR’s perceived indifference and inaction on their behalf.