A joint report from the Uyghur Human Rights Project and the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs by Bradley Jardine and Robert Evans. Read our press statement on the report here, and download the full report here. Cover design by YetteSu.

I. Executive Summary

“Nets Cast from the Earth to the Sky” explores how China has targeted Uyghurs in Pakistan and Afghanistan since the late 1990s in order to silence dissent. The report distinguishes different methods by which the Chinese government represses Uyghur communities in Pakistan and Afghanistan and determines how these methods violate international human rights and legal norms. The report also chronicles China’s engagement with its fiercest ally, Pakistan, over the past 40 years in order to demonstrate how increased engagement between the two countries correlates with a growing humanitarian crisis for Uyghurs living in the region. To this end, we gathered cases of China’s transnational repression of Uyghurs in Pakistan and Afghanistan from interviews with Uyghur activists and refugees in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Turkey, in addition to government documents and human rights reports, and Urdu and English media.

Our work draws from the China’s Transnational Repression of Uyghurs Dataset, a joint project by the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs and the Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP).1“China’s Transnational Repression of Uyghurs” (database), Oxus Society and Uyghur Human Rights Project, last accessed August 10, 2021, https://oxussociety.org/viz/transnational-repression/ From our dataset, we have identified and analyzed 21 cases of detention and deportation in Afghanistan and Pakistan, with an upper estimate of 90 reported incidents lacking full biographical records.

The PRC is able to target Uyghurs outside its borders with the help of the neighboring host governments. For example, in Pakistan China entices the government with large development projects like the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) in order to secure its support against Uyghurs. This report demonstrates several instances in which China rewarded Pakistan for aiding its campaign against Uyghurs. In exchange for development assistance, Pakistan signed extradition treaties, arrested individuals at China’s request, and rebuked critics of China’s harsh policies, all of which made it easier for China to continue repressing Uyghurs.

The report also illustrates how China utilizes international organizations to shape perception of Uyghurs globally. China aims to frame its campaign against Uyghurs as “counterterrorism” and uses international mechanisms and organizations to legitimize its actions, particularly in the Muslim world. These tactics also deepen security ties with countries hosting Uyghurs, allowing China to more easily target Uyghurs outside its borders.

Through its strategy of offering extravagant development projects while deepening security ties, China has successfully gained influence over Pakistan’s government and thus its Uyghur community. China is now attempting to implement this strategy in other countries with sizable Uyghur populations. As the Taliban gains territory in Afghanistan, Pakistan is portraying itself and China as facilitators of peace and development. China will use the chaos in Afghanistan to further justify its crackdown on Uyghurs, who express fear about their future in the country.2Reid Standish, “China Cautiously Eyes New Regional Leadership Role As Afghanistan Fighting Intensifies,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty,July 14, 2021, https://www.rferl.org/a/china-region-afghanistan conflict/31358035.html

We make a number of policy recommendations to the government of Pakistan, the UN, and members of the international community, including the following:

- For governments to impose targeted sanctions on Chinese citizens responsible for acts of transnational repression through sanction mechanisms like the Global Magnitsky Act.

- For governments to increase quotas for the resettlement of Uyghur refugees, given that traditional safe havens for Uyghurs are increasingly insecure.

- For the government of Pakistan to reform or abolish laws that give intelligence groups broad authority to investigate and imprison individuals.

- For the United Nations to investigate allegations against the UNHCR office in Pakistan, given the alarming testimony that Uyghur refugees are being denied asylum services by the UNHCR office in Islamabad.

II. Introduction

Chaudhry Javed Atta, a Pakistani dried fruits trader with business in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), last saw his Uyghur wife in August 2017.3In this report, we refer to the Uyghur homeland interchangeably as “the Uyghur Region” and “the XUAR” (short for “Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region”). Uyghurs around the world see “Xinjiang,” the shortened form of “Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region,” which Chinese authorities prefer, as a colonial term. In addition to “Uyghur Region,” many Uyghurs also refer to their homeland as “East Turkistan” (sometimes “East Turkestan”), a historical name by which the region was long known but the use of which is considered “separatist,” and thus one of the “three evils,” in the PRC. That year, when he had to return to Islamabad to renew his visa, she told him, “As soon as you leave, they will take me to a camp, and I will not come back.” He has not heard from her since.4“Locked Away, Forgotten: Muslim Uyghur Wives of Pakistani Men,” Dawn, December 17, 2018, https://www.dawn.com/news/1451965

Following Chinese President Xi Jinping’s 2014 call for “nets cast from the Earth to the sky,” signaling a harsher turn for security in the Uyghur homeland, police officials began operating secret blacklists on 26 primarily Muslim-majority countries, including Pakistan.

For Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples living in the Uyghur Region, links to Pakistan can be dangerous. Following Chinese President Xi Jinping’s 2014 call for “nets cast from the Earth to the sky,” signaling a harsher turn for security in the Uyghur homeland, police officials began operating secret blacklists on 26 primarily Muslim-majority countries, including Pakistan. Chinese authorities label any communication, connections, or travel history from residents of the XUAR to these blacklisted countries as suspicious. Combined with a powerful system of algorithmic surveillance, these blacklists have resulted in the deportation of Uyghur students from around the world back to the XUAR, as well as their arrest, imprisonment, and even death.5“Two Uyghurs Returned From Egypt, Dead in Chinese Police Custody,” Middle East Monitor, December 22, 2017, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20171222-2-uyghur-students-returned-from-egypt-dead-in-china-police-custody/ Since early 2017, an estimated 1.8 million Turkic peoples have been arbitrarily rounded up in concentration camps, which China euphemistically refers to as “re-education” or “vocational training” centers, with possibly millions more incarcerated in the Chinese prison system or conscripted into forced labor in factories around the country.6For internment figures, including upper estimate of 1.8 million in concentration camps as of 2019, see Adrian Zenz, “‘Wash Brains, Cleanse Hearts’: Evidence from Chinese Government Documents about the Nature and Extent of Xinjiang’s Extrajudicial Internment Campaign,” Journal of Political Risk 7, no. 11, (November 2019), https://www.jpolrisk.com/wash-brains-cleanse-hearts/. For a recent investigation showing that the XUAR government is capable of detaining a minimum of 1.01 million individuals at one time, see Megha Rajagopalan and Allison Killing, “China Can Lock Up a Million Muslims in Xinjian at Once,” Buzzfeed News, July 21, 2021, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/meghara/china-camps-prisons-xinjiang-muslims-size. For details on the scale and scope of the forced labor program, see Vicky Xiuzhong Xu, Danielle Cave, James Leibold, Kelsey Munro, and Nathan Ruser, “Uyghurs for Sale,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, March 1, 2020, https://www.aspi.org.au/report/uyghurs-sale

Pakistani men like Chaudhry Javed Atta and hundreds of others whose Uyghur wives have also been detained by Chinese authorities had hoped that Islamabad would speak up on their behalf. For decades, Pakistan has been at the forefront of advocacy on behalf of oppressed Muslim communities around the world, from Myanmar’s persecuted Rohingya to India’s harshly treated Muslim communities.7Human Rights Watch, “‘Shoot the Traitors’: Discrimination Against Muslims Under India’s New Citizenship Policy,” April 9, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/04/09/shoot-traitors/discrimination-against-muslims-under-indias-new-citizenship-policy# On the subject of China’s industrial-scale repression of Turkic peoples in the XUAR, however, Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan has either avoided questions on the matter or claimed to know nothing about the issue.8Ben Westcott, “Pakistan’s Khan Dodges Question on Mass Chinese Detention of Muslims,” CNN, March 28, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/03/28/asia/imran-khan-china-uyghur-intl/index.html; Jonathan Swan, “Pakistan PM Imran Khan; Sec Marcia Fudge; Fmr Rep Katie Hill; United,” Axios, June 20, 2021, https://play.hbomax.com/page/urn:hbo:page:GYHdzdg0tl5HDZgEAAAAE:type:episode

Pakistan’s response to China’s XUAR policies, which combines denialism, rhetorical support, and complicity, has structural underpinnings. For decades, China has been Pakistan’s largest patron, providing it with everything from infrastructure and military equipment to nuclear technology. Both sides speak fondly of this bond, calling it an all-weather friendship.9Nazir Naji, “عظیم مہمان کے لئے‘ محبت کے چند پھول” [For an amazing guest, a few flowers of love], Dunya, May 23, 2013, https://dunya.com.pk/index.php/column-detail-print/2993 Still, in 2020, Khan put relations in much starker terms: “As far as the Uyghurs, look—China has helped us. China came to help our government when we were at rock bottom.”10Jonathan Tepperman, “Imran Khan on Trump, Modi, and why he Won’t Criticize China,” Foreign Policy, January 22, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/01/22/imran-khan-trump-modi-china/ However, growing relations have posed an existential threat to Pakistan’s small Uyghur community in the city of Rawalpindi. According to data we collected, Pakistan has been actively collaborating with Chinese security services to arrest, detain, and extradite Uyghur citizens and asylum applicants to placate its powerful neighbor since 1997.

Meanwhile, the Chinese government is attempting to replicate this strategy in Afghanistan, Pakistan’s deeply interconnected neighbor, where there is also a sizeable Uyghur community and where China has been in regular talks with leadership from the Taliban, who are poised to take political control of the country. In Pakistan, a member of Imran Khan’s cabinet recently encouraged dialogue with a “civilized Taliban,” referring to China’s Belt and Road project as an incentive for the Taliban.11Aamir Yasin, “New, civilised Afghan Taliban may prefer talks to guns: Rashid,” Dawn, July 12, 2021, https://www.dawn.com/news/1634561/new-civilised-afghan-taliban-may-prefer-talks-to-guns-rashid Meanwhile the Pakistani National Security Advisor has suggested that militants might flee Afghanistan disguised as refugees.12“If Afghanistan descends into war, govt won’t let fallout affect Pakistan: Fawad,” Dawn, July 12, 2021, https://www.dawn.com/news/1634656/if-afghanistan-descends-into-war-govt-wont-let-fallout-affect-pakistan-fawad These statements by key Pakistani officials clearly echo China’s rhetoric regarding Uyghurs in bordering countries, signaling that the Taliban appears to be responsive to entrées by China.13Amy Chew, “China a ‘welcome friend’ for reconstruction in Afghanistan: Taliban spokesman,” South China Morning Post, July 9, 2021, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3140399/china-welcome-friend-reconstruction-afghanistan-taliban Uyghurs in Afghanistan and around the world are beginning to openly express fear at the growing relationship between China and the Taliban, and the implications that relationship might have.

According to data we collected, Pakistan has been actively collaborating with Chinese security services to arrest, detain, and extradite Uyghur citizens and asylum applicants to placate its powerful neighbor since 1997.

Drawing from original interviews conducted in Urdu and English, in addition to Urdu source materials, this report aims to provide a comprehensive account of Chinese transnational repression of Uyghurs in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

III. Methodology

The following report, part of a series on China’s attempt to control Uyghur activism around the globe, makes use of the China’s Transnational Repression of Uyghurs Dataset, established by the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs in partnership with UHRP to monitor global cases of Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples intimidated or repressed beyond China’s borders.14“China’s Transnational Repression of the Uyghurs” [database], Oxus Society, June 24, 2021, https://oxussociety.org/viz/transnational-repression/. See also Bradley Jardine, Edward Lemon, and Natalie Hall, “No Space Left to Run,” Oxus Society and Uyghur Human Rights Project, June 24, 2021, https://uhrp.org/report/no-space-left-to-run-chinas-transnational-repression-of-uyghurs/ and https://oxussociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/transnational-repression_final_2021-06-24-1.pdf The China’s Transnational Repression of Uyghurs Dataset includes 300 fully verified cases of detentions or renditions of Uyghurs living overseas, with an upper total of 1,546 cases. In Afghanistan and Pakistan, we have a total of 21 of these cases, with an upper estimate of 90 reported incidents lacking biographical details. We have based these figures on public reporting by investigative journalists in Pakistan; they likely represent just a small portion of the total renditions and detentions that have occurred in secret.

Additionally, this research references key informant interviews (KII) in Urdu and Uyghur, which we conducted online with prominent activists such as Umer Khan. These interviews helped us to build an understanding of the development of Uyghur civil-society activism in Pakistan and the forms of pressure, surveillance, and intimidation Uyghurs in the country are experiencing today. Complementing the KIIs are a number of interviews we conducted with Uyghur refugees, many of whom requested anonymity due to potential threats to their lives. The report also makes use of a large number of secondary sources in English, Chinese, and Urdu, including traditional print sources, digital sources, broadcast sources, social media, and reported personal accounts by Uyghurs undergoing forms of transnational repression.

IV. Autocracy Beyond Borders

China’s targeting of Uyghur minorities in Pakistan is nothing novel but rather is part of a broader strategy of what scholars such as Dana Moss have termed “transnational repression.”15Dana M. Moss, “Transnational Repression, Diaspora Mobilization, and the Case of The Arab Spring,” Social Problems 63, no. 4 (November 2016): 480–98. For the purposes of this report, repression refers to any actions which raise the stakes for cultural or political activism, moderating or discouraging such behavior. Repression has traditionally taken place within a particular state’s jurisdiction and territory. However, autocratic regimes are now increasingly wielding their considerable resources to shape discourse and stifle dissent overseas. Throughout the twentieth century, states have utilized strategies of infiltration, spying, and even extra-judicial killings to silence opposition in exile.

In the 1980s, for example, Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi ordered his country’s security services to coordinate an international assassination program that reached into the United Kingdom. During this period, the Gaddafi regime targeted Libyan dissidents in the United Kingdom with attacks. Bombs went off outside apartments occupied by Libyans, and Libyan embassy staff even fired upon an anti-Gaddafi demonstration, infamously killing a British police officer.16Jon Nordheimer, “Libyan Exiles in Britain Live in Fear of Qaddafi Assassins,” New York Times, April 26, 1984, https://www.nytimes.com/1984/04/26/world/libyan-exiles-in-britain-live-in-fear-of-qaddafi-assassins.html

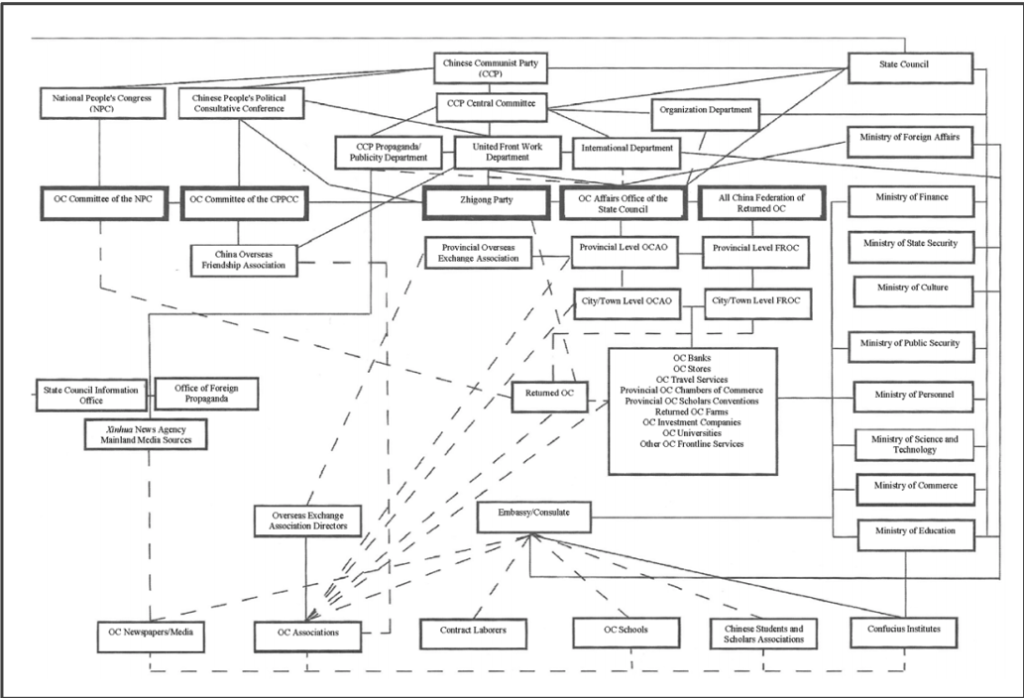

Evidence suggests that the scale of such activities has increased dramatically in recent years. In its recent report on transnational repression, “Out of Sight, Not Out of Reach,” Freedom House documented 608 incidents of transnational repression globally since 2018 and identified China as the most prolific perpetrator of the practice.17Nate Schenkkan and Isabel Linzer, “Out of Sight, Not Out of Reach,” Freedom House, January 2021, https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2021-01/FH_TransnationalRepressionReport2021_rev012521_web.pdf China’s engagement with overseas communities has attracted significant attention over the past four decades. At the time of its establishment in 1978, many countries viewed the “Overseas Chinese Affairs Office,” overseen by the powerful State Council, with suspicion, wary of the implicit assumption that members of their own populations are still considered “Chinese minorities” under jurisdiction of the PRC.18Alessandro Rippa, Borderland Infrastructures: Trade, Development, and Control in Western China, (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2020), p. 184. Since then, a dizzying array of associations have sprung up around the world, tasked with expanding Beijing’s ideological presence among diaspora communities.19Pal Nyiri, New Chinese Immigrants in Europe (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999).

Today, the overseas Chinese community is estimated to number anywhere between 10 million and 50 million people.20“The Chinese Diaspora: Historical Legacies and Contemporary Trends,” US Census Bureau, August 2019, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2019/demo/Chinese_Diaspora.pdf, p. 4; Huiyao Wang, “China’s Competition for Global Talents: Strategy, Policy and Recommendations,” Asia Pacific (May 2012): 2. Ethnic groups such as the Uyghurs also fit within the framework of “overseas Chinese,” with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) advocating an official discourse on Uyghurs as part of the “unity of nationalities” (minzu tuanjie 民族团结), even when they live outside the PRC.21James Jiann Hua To, “Qiaowu: Extra-Territorial Policies for the Overseas Chinese,” The China Quarterly 221, (May 2014): 191–226.

The Ex Chinese Association in Pakistan offers an important case study regarding the methodologies China adopts to influence the Uyghur diaspora. The Chinese government makes use of such organizations to win the political loyalty of Uyghurs residing in Rawalpindi and other parts of Pakistan, similar to how it uses these organizations in engagement with Han Chinese communities around the world. The XUAR’s local government is also active in transnational repression of Uyghurs, operating through an organization called the “Xinjiang Overseas Exchange Association,” which was established in 1992 with the goal of fostering loyalty via the promotion of cultural exchange programs. In 2012, for example, Chinese authorities invited a small delegation of Pakistani Uyghurs to Beijing as part of the “Delegation of overseas Chinese minorities from Xinjiang.”22Rippa, Borderland Infrastructures, p. 184.

In Pakistan, China is arguably more invasive with these tactics than in any other part of the world, using state security agencies, diaspora groups, international groups, and the Pakistani government to discourage any form of Uyghur activism or cultural expression.

Since Xi Jinping’s rise to power in 2013, the CCP has adopted a more severe approach toward overseas communities under the guise of a sweeping anti-corruption campaign, introducing “Operation Foxhunt” (猎狐行动) as the international side of Xi’s domestic campaign of rooting out “tigers and flies,” or corrupt officials within the CCP’s ranks. The operation reportedly utilized up to 2,000 personnel to achieve its goals, with over 70 police teams sent overseas to seek out “economic fugitives.” According to state media, a similar campaign called “Operation Skynet” (天网行) was launched in April 2015, with both Operations “Skynet” and “Foxhunt” resulting in the capture of around 4,058 fugitives from over 70 countries.23“China’s ‘Sky Net’ Campaign Nabs More Than 4,000 Fugitives Since 2015,” CGTN, April 24, 2018, https://news.cgtn.com/news/3d3d414e3559444d77457a6333566d54/index.html During this time, China has doubled down on its strategies toward “ethnic minority” communities abroad, employing tactics such as espionage, cyberattacks, and threats of physical assault. In Pakistan, China is arguably more invasive with these tactics than in any other part of the world, using state security agencies, diaspora groups, international groups, and the Pakistani government to discourage any form of Uyghur activism or cultural expression.

V. Pakistan, China, and International Violations of Human Rights Frameworks

Pakistan and China have both ratified a relatively small number of human rights treaties. Nevertheless, we have identified numerous violations of this small number of human rights treaties to which both countries are signatories. Though these treaties are non-binding and purposefully contain broad language, they nevertheless impose humanitarian norms on their signatories.

United Nations: Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT)

Article 3 states, “No state party shall expel, return (‘refouler’) or extradite a person to another state where there are substantial grounds for believing that he would be in in danger of being subjected to torture.”24UN General Assembly, Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, 10 December 1984, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1465, p. 85. Pakistan ratified this treaty in 2010, and China ratified it in 1988. According to our analysis, Ismail Semed (2003) and Osman Alihan (2007) reported torture after being returned to China prior to Pakistan ratifying the treaty. Generally, the international community views the Convention against Torture to be a peremptory norm of general international law due to its universal recognition. Therefore, Pakistan was in violation of international human rights norms even though it was not yet a signatory of the convention in the cases mentioned above. No direct cases of torture have been mentioned since ratification, according to the China’s Transnational Repression of Uyghurs Dataset, but that is likely an issue of sparse information, not an actual absence of such cases. Torture remains widespread and well-documented in the Uyghur homeland today,25Human Rights Watch, “China: Crimes Against Humanity in Xinjiang,” April 19, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/04/19/china-crimes-against-humanity-xinjiang with high risk of detentions and even death for those who return.26“Two Uyghur Students Die in China’s Custody Following Voluntary Return from Egypt,” Radio Free Asia, December 21, 2017, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/students-12212017141002.html It is therefore likely that at least some recent returnees from Pakistan have suffered a similar fate.

Meanwhile, Article 15 of the Convention states, “Each state party shall ensure that any statement which is established to have been made as a result of torture shall not be invoked as evidence in any proceedings, except against a person accused of torture as evidence that the statement was made.” Ismail Semed, noted above, was placed on a 2003 wanted list issued by the Ministry of State Security. However, the charges that led to his inclusion on the list appear to have been based on testimony of two Uyghurs in the Uyghur Region who were tortured and executed, suggesting authorities likely obtained their confessions and incrimination of Mr. Ismail by force.27Human Rights Watch, “China: Account for Uyghur Refugees Forcibly Repatriated to China,” January 28, 2010, https://www.refworld.org/docid/4b6abe8d1e.html

United Nations: Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Article 15, clause 2 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states, “No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality,” while Article 20, clause 2 states, “No one may be compelled to belong to an association.” Interviews we conducted with Pakistani Uyghurs have identified an alarming trend in both China and Pakistan in which their governments violate these laws en masse.

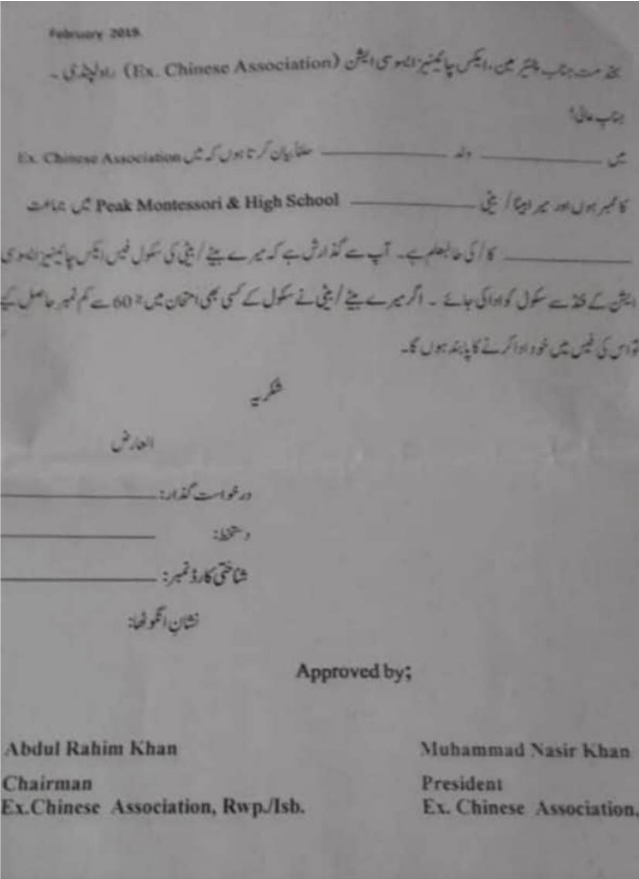

Since 2017, surveillance of Pakistan’s Uyghur community has also significantly increased, largely due to the efforts of the Ex Chinese Association, which in recent years was going door to door in Uyghur neighborhoods in Rawalpindi distributing “registration forms.” The forms are ostensibly produced to allow Uyghur children to attend Chinese Embassy-run school programs for free. “Many of the families are living below the poverty line and sign these forms in exchange for basic food items like bread and rice,” said Umer Khan, who added that the registration forms may be used by the Chinese government to monitor the population or extradite them to the XUAR to face internment. He went on: “A large number of people signing the list are illiterate and sign using their fingerprints. After they sign, they are no longer viewed as simply Pakistani, but as Chinese subjects.”28Muhammad Umer Khan (Uyghur activist), interview by Bradley Jardine and Robert Evans, April 14, 2021.

This coercion shows how China perceives security within the XUAR and the question of Uyghurs living abroad. To China, the fact that the Uyghurs signing these documents could be Pakistani citizens is inconsequential; in the Chinese government mindset, their ethnicity and proximity to China’s border region justifies this type of harsh transnational repression.

These trends also appear to demonstrate the spread of Chinese domestic practices internationally, with intrusive data-gathering in the Uyghur homeland being a routine component of community surveillance and predictive policing (i.e., the practice of gathering and using data to determine would-be criminals). In 2015, for example, Human Rights Watch reported that Uyghurs were being forced to submit bio-data with their passport applications, including “a DNA sample, a voice sample, a 3D image of themselves, and their fingerprints.”29Human Rights Watch, “China: Account for Uyghur Refugees.” This type of personal data now feeds into massive Chinese state databases like the Integrated Joint Operating System (IJOP), which then sorts individuals on different levels of “trustworthiness.”30Human Rights Watch, “China’s Algorithms of Repression,” May 1, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/05/01/chinas-algorithms-repression/reverse-engineering-xinjiang-police-mass

So far, the Ex Chinese Association may have claimed as many as 400 names in Pakistan. The group’s Facebook page regularly posts political messages defending China’s repressive policies in the XUAR.

While the organization has a documented history of receiving funding from the Chinese Embassy, officials from the same embassy have nevertheless taken to distancing themselves from the organization. Zhao Lijian, former deputy chief of mission at the Chinese Embassy in Islamabad and current spokesperson for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, went so far as to claim in a recent report that he was not even aware of the organization’s existence.32Zuha Siddiqui, “China Is Trying To Spy On Pakistan’s Uighurs,” Buzzfeed News, June 20, 2019, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/zuhasiddiqui/china-pakistan-uighur-surveillance-ex-chinese-association However, Zhao was photographed with members of the Ex Chinese Association as recently as June 6, 2019.

In an interview, Omar Uyghur Trust founder Umer Khan told us that he has helped at least 37 Uyghur families escape the XUAR into Pakistan, and from there to Turkey. “The UNHCR isn’t helping these people, and whenever I take them to the main office in Islamabad, the staff are hostile and refuse to register Uyghur cases,” he said. We also interviewed several of the refugees in Umer’s care on the condition of anonymity. These refugees described their lives in Pakistan as characterized by constant anxiety. One family told us that their father left their safehouse one day and never returned. Now the rest of the family refuses to leave the house out of fear of a similar fate.

One woman described her terrified state of mind: “If anyone even knocks on the door, I scream that it’s the Chinese government coming to take us back to China.” Abdulaziz Naseri, a Uyghur refugee living in Turkey, agreed to go on the record for this report. He belongs to a Uyghur family that moved from the XUAR to Kabul in 1976 to escape the “cruelty of the Communist Party and their killing of Muslims.” After seven years in Kabul, Abdulaziz’s family moved to Pakistan to escape the Soviet invasion. In June 2019, Abdulaziz came to Turkey to attend a conference called the “East Turkestan Brotherhood Meeting,” but during his trip his parents were detained in Pakistan in retaliation for his activism. Now Abdulaziz says that if he returns to Pakistan, he will be arrested or his parents will be further harassed. “I am afraid for my parents still living in Pakistan,” he told us.34Abdulaziz Naseri (Uyghur refugee), interview by Bradley Jardine and Robert Evans, April 15, 2021.

Abdulaziz echoes Umer Khan’s frustration with the UN, saying, “We have applied many times to the United Nations, but we are without hope. They will never help us.” Khan himself was arrested in 2017 when numerous cars came to his house to detain him.35Siddiqui, “China Is Trying To Spy On Pakistan’s Uighurs.” Speaking about this arrest, he said he believes local authorities wanted to make a spectacle out of his arrest to make his neighbors think he was dangerous. He was held for several days, during which the authorities subjected him to torture, and he still suffers from torture-inflicted injuries.

Since the Taliban gained control of more than 50 percent of Afghan provinces at the end of July 2021, Uyghurs in Afghanistan have begun feeling an urgent danger.36Bill Roggio, “Mapping Taliban Contested and Controlled Districts in Afghanistan,” FDD’s Long War Journal, August 4, 2021, https://www.longwarjournal.org/mapping-taliban-control-in-afghanistan In a series of voice messages sent to us in August 2021, Abdulaziz Naseri described the new anxiety Afghan Uyghurs feel as the Taliban are poised to take control of the country. Abdulaziz explained that when he and his family fled the XUAR for Afghanistan many years ago, their Afghan identification forms listed each member of the family as “Chinese migrant.” Despite living in Afghanistan for several years and even having gained Afghan citizenship, his ID form still labels him as a “Chinese migrant” where the same forms simply list most Afghans as simply “Afghan.”

One woman described her terrified state of mind: “If anyone even knocks on the door, I scream that it’s the Chinese government coming to take us back to China.”

Abdulaziz now fears that China could be making a deal with the Taliban to access these ID forms. He told us that it would be fairly easy to investigate who is of Uyghur origin based on this “Chinese migrant” distinction listed on the form. He claims to know of approximately 20 families in Afghanistan who have similarly marked documents, and he fears that authorities in other countries will single them out as they flee the country and apply for residency or citizenship in other countries. The fact that their Afghan documents will still label them as “Chinese migrants” may be grounds to deny them entry visas, which Abdulaziz and others fear might turn Uyghurs into direct targets of transnational repression. Whether these Afghan Uyghurs choose to stay in regions now under Taliban control or attempt to flee for any neighboring countries, the label of “Chinese migrant” on their documents will expose them to incredible danger.37Abdulaziz Naseri, personal communication with Robert Evans, August 5, 2021. This and all other translations from Urdu into English by Robert Evans.

Although Pakistan is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention, it did vote in favor of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and thus has a moral obligation to uphold the norms in the Declaration. Therefore, the denial of asylum services by the UNHCR office and the harassment of Uyghur refugees that these activists describe represent violations by Pakistan of this foundational human rights document, specifically Article 14, which guarantees the right of individuals to seek asylum from persecution.

Additionally, Khan’s brutal account of being detained and beaten by Pakistani security forces is a violation of another human rights treaty that Pakistan signed: the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. No lawful Pakistani ordinance sanctioned Khan’s suffering; rather, authorities intimidated and discriminated against him solely for his role as a prominent ethnic minority activist. Such actions on the part of the authorities are forbidden by Article 1 of the Convention Against Torture. Khan’s account is part of a larger trend in Pakistan of the harassment, torture, and forced disappearances of political, religious, and ethnic activists heightened by Islamabad’s deepening cooperation with Beijing as it seeks to target Uyghurs living in the country.38Amnesty International, “Pakistan: Crackdown on human rights intensifies,” January 30, 2020, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/01/2019-pakistan-in-review/

Despite both China and Pakistan displaying patterns of human rights violations, both countries have been elected to leadership roles at the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) as recently as October 2020.39United Nations, “Election of the Human Rights Council,” October 13, 2020, https://www.un.org/en/ga/75/meetings/elections/hrc.shtml The presence of the two countries on the UNHRC raises troubling questions about the UN’s credibility as an arbiter for human rights law, as well as about China’s attempts to control the narrative of its human rights violations against the Uyghurs. Leaked emails confirmed that the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights provided the names of Uyghur activists who actively attended panel discussions and conferences on human rights from 2012 to 2015, all at the request of the Chinese government.40Bayram Altug and Serife Cetin, “Leaked emails confirm UN passed info to China in name-sharing scandal,” Anadolu Agency, January 18, 2021, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/europe/leaked-emails-confirm-un-passed-info-to-china-in-name-sharing-scandal/2114163 In fact, the UNHRC office said they “regularly” complied with these requests from China for activists’ names. China carries significant weight in the UNHRC, stressing “win-win cooperation,” a framework that positions human rights standards as merely voluntary cooperation rather than a legal obligation.41Human Rights Watch, “China’s Global Threat to Human Rights,” 2019, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2020/country-chapters/global#606fd8

According to Human Right Watch, Chinese officials in the past three years have been threatening delegations critical of its conduct in the Uyghur homeland and have utilized UN meetings for propaganda purposes to depict Uyghurs as “happy.”42Ibid. Although the UNHRC began requesting access to the Uyghur homeland in order to conduct an investigation into human rights abuse allegations in March 2019, the Chinese government would not commit to allowing a UNHRC team full and unfettered access to the region to conduct the investigation.43Sophie Richardson, “China’s Weak Excuse to Block Investigations in Xinjiang,” Human Rights Watch, March 25, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/25/chinas-weak-excuse-block-investigations-xinjiang As of August 2021, many international observers are demanding an independent investigation into possible human rights abuses in the region, but the Chinese government continues to deny unmitigated access to independent investigators.44Louis Charbonneau, “UN Chief Should Support Remote Investigation in Xinjiang,” Human Rights Watch, April 8, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/04/08/un-chief-should-support-remote-investigation-xinjiang

VI. Mechanisms for Transnational Repression

In order to circumvent international law and conduct transnational surveillance, intimidation, and repression, the Chinese government employs a wide range of institutions and instruments, which we explore in detail below.

China’s Security Apparatus

The primary agencies involved in transnational repression in Pakistan are the powerful internal security services linked to the CCP, including the Ministry of State Security (MSS) and the Ministry of Public Security (MPS). In the Pakistani context, the MSS has issued local intelligence with lists of wanted Uyghurs in 2003,45“China Names Six Uighurs on Terror List,” BBC, April 6, 2012, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-17636262 2007,46Wajid Ali Wajid, “China Worried About Rising Extremism,” Gulf News, June 25, 2007, https://gulfnews.com/world/asia/pakistan/china-worried-about-rising-extremism-1.185775 and 2012,47Jamestown Foundation, “Uyghur Militants Respond to New Chinese List of ‘Terrorists,’” Terrorism Monitor, May 4, 2012, https://www.refworld.org/docid/4fa7a3752.html resulting in arrests and extraditions. The MPS meanwhile prioritizes the intimidation of families with relatives living or working in Pakistan due to the country’s “blacklisted” nature. The MPS has been particularly active with regard to Pakistani nationals in recent years, dividing families to exert control. The Xinjiang Victims Database, a Kazakhstan-based data-collection project that documents Uyghur detentions in the XUAR, has a large amount of information on Uyghur wives separated from their Pakistani husbands due to internment, with evidence of the wives being used to intimidate their husbands in Pakistan to prevent them from speaking out.48“Entry: Melike Memet,” Xinjiang Victims Database, September 30, 2018, https://shahit.biz/eng/viewentry.php?entryno=24 In some cases, Chinese authorities stop Pakistani husbands trying to cross the border into the Uyghur Region and tell them they must be accompanied by their Uyghur wives to gain entry. After returning together to the XUAR, the Chinese authorities then order the Uyghur wives to report to the police daily, while the Pakistani husbands’ visas are usually canceled, after which the husbands are ordered to leave China.49“Pakistani Men Seek Release of Uyghur Wives Locked in China Camps,” Dawn, December 18, 2018, https://www.dawn.com/news/1452064 Families still in Pakistan believe their communication with these detained wives are bugged, so they do not approach anyone for help, fearing backlash from Beijing.50S. Khan, “Pakistani Husbands Distressed as Uyghur Wives Face Chinese Crackdown,” Deutsche Welle, February 15, 2019, https://www.dw.com/en/pakistani-husbands-distressed-as-uighur-wives-face-chinese-crackdown/a-47540441

United Front Work

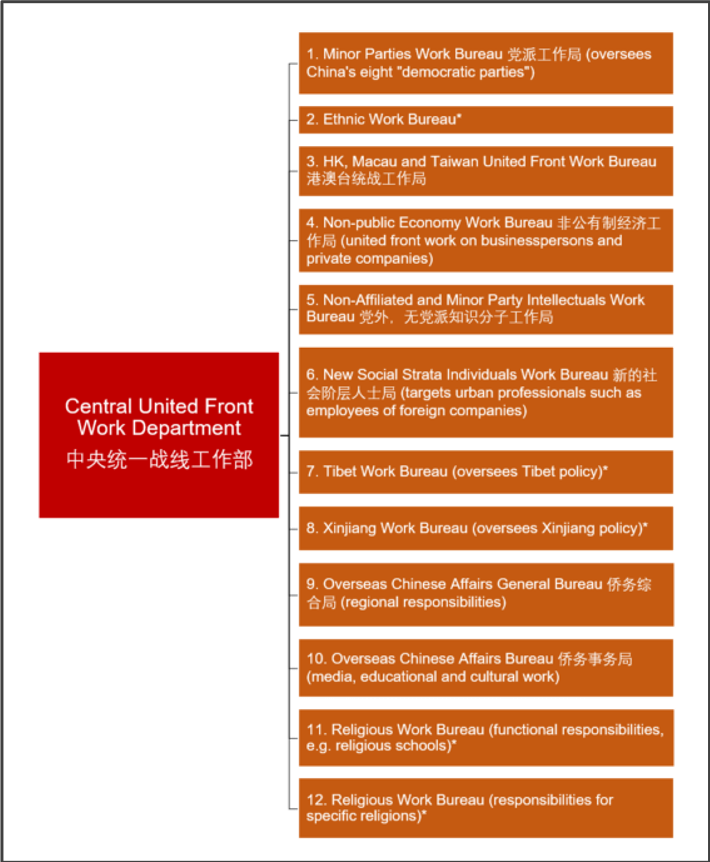

China also engages in transnational repression in Pakistan through the CCP’s United Front Work Department (UFWD), which coordinates the activities of everything from influencers to student organizations as a means of gaining intelligence and shaping pro-China discourse abroad. The UFWD is a high-level department that answers directly to the CCP’s Central Committee and is coordinated by a group led by a member of China’s Politburo Standing Committee. This organizational structure puts UFWD on approximately equal footing with other high-level CCP organizations, such as the International Liaison Department, the Organization Department, and the Propaganda Department.51Marcel Angliviel de la Beaumelle, “The United Front Work Department: ‘Magic Weapon’ at Home and Abroad,”China Brief, Jamestown Foundation, July 6, 2017, https://jamestown.org/program/united-front-work-department-magic-weapon-home-abroad/ The UFWD has received newfound importance in the Xi Jinping era, with almost 40,000 new cadres recruited in their first year in office and almost all Chinese embassies now employing UFWD personnel.52Graeme Smith, “China: magic weapons and ‘plausible deniability,’” Lowy Institute, April 30, 2018, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/plausible-deniability-and-united-front-work-department. Alex Joske, “Reorganizing the United Front Work Department: New Structures for a New Era of Diaspora and Religious Affairs Work,” China Brief, Jamestown Foundation, May 9, 2019, https://jamestown.org/program/reorganizing-the-united-front-work-department-new-structures-for-a-new-era-of-diaspora-and-religious-affairs-work/ The department is separated into nine bureaus, each responsible for a specific group that China targets for co-option and subversion. The UFWD includes a bureau responsible for China’s ethnic minorities, a bureau for China’s international diaspora, and a bureau for the XUAR, among others.

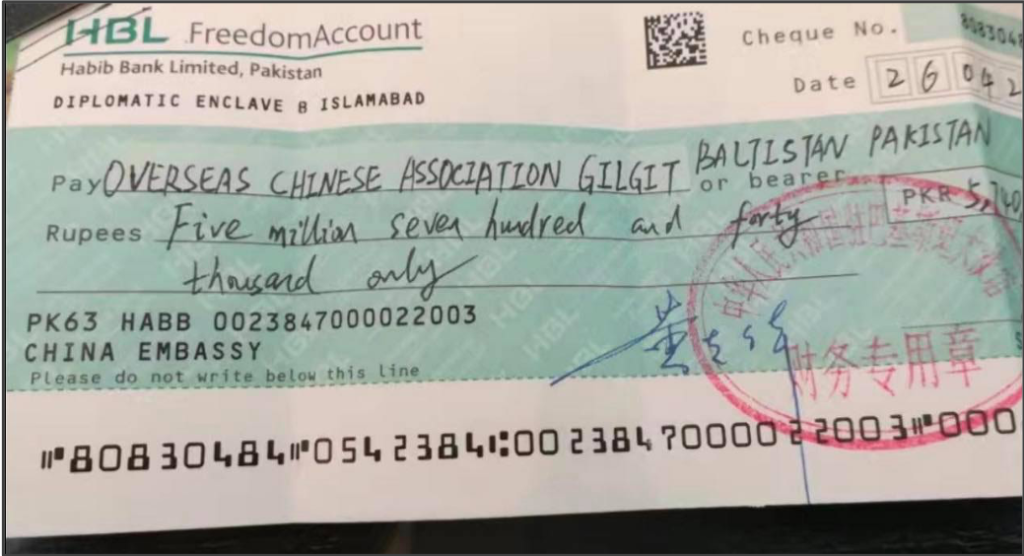

As we note above, the Ex Chinese Association, which conducts UFWD work, has taken an unusually prominent role in spearheading transnational repression of Uyghurs in Pakistan. Established in 2003, the Ex Chinese Association in Pakistan received 16 million rupees ($150,000 USD) from the Chinese embassy, as well as additional grants issued in 2013 with the aim of educating the sons and daughters of Pakistani Uyghurs.54Siddiqui, “China Is Trying To Spy On Pakistan’s Uighurs.” Originally tasked with fostering ideological loyalty to the Chinese state, the association has expanded its tasks substantially since 2017, with evidence emerging of the association actively monitoring Rawalpindi’s Uyghur community. According to our interviews, the Ex Chinese Association has been distributing registration forms ostensibly designed to allow Pakistani Uyghurs to attend schooling and other activities organized through the Chinese embassy. Activists in Pakistan, a country with 50 recorded cases of illegal detentions and renditions according to the China’s Transnational Repression of Uyghurs Dataset, say the lists are a tool for enhanced Chinese coercion. On its official Facebook page, the organization frequently posts articles that defend China’s policies in the XUAR.55For just one example, see “پاکستان میں یوریشین سنچری انسٹی ٹیوٹ کے بانی صدر نے کہا ہے کہ سنکیانگ کے حوالے سے جھوٹ بنیادی طور پر چین کی پیشرفت کے خوف سے پیدا کیے جا رہے ہیں.” [“The founding president of the Eurasian Century Institute in Pakistan has said that lies about Xinjiang are being created mainly out of fear of China’s progress.”], 2020, Ex Chinese Association Pakistan Facebook Group, March 19, 2020, https://www.facebook.com/ExChinesePak1/

Chinese embassies and consulates, directed by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, have long taken an active role in intimidating Uyghurs in this part of the world.

In addition, Chinese embassies and consulates, directed by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, have long taken an active role in intimidating Uyghurs in this part of the world. In 2006, the Chinese embassy reportedly placed pressure on the Saudi embassy in Islamabad to deny visas to thousands of Uyghurs seeking to embark on the hajj pilgrimage. According to a report, Chinese officials at the embassy threatened Uyghur protest leaders who opposed the move.56“Refugee Review Tribunal: CHN31261,” Australian Refugee Review Tribunal, February 9, 2007, https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/4b6fe16f0.pdf In 2015, the Chinese consulate in Pakistan was reported to be distributing money to local Uyghurs in Rawalpindi in exchange for information about protest leaders.57“Chinese Consulate Pays off Uyghurs in Pakistan for Dirt on Activists,” Radio Free Asia, July 23, 2015, https://www.refworld.org/docid/55e59c73c.html As part of a “charm offensive” in 2018, the Chinese embassy in Islamabad extended an invitation to about a dozen Uyghur community leaders from Pakistan to visit the XUAR and meet Chinese officials.58Adnan Aamir, “Beijing Engages with Pakistan’s Uyghurs in ‘Charm Offensive,’” Nikkei Asia, October 31, 2018, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Beijing-engages-with-Pakistan-s-Uighurs-in-charm-offensive

Diaspora Spies and Informants

China also tries to instill fear and suspicion among Uyghur communities using networks of spies and informants to sever social ties, such as the case of Yusupjan Ahmet, whom Chinese authorities pressed to spy on Uyghur communities in Turkey after threatening his mother.59“Man ‘forced’ to inform on fellow Uighurs for China is shot in Turkey,” The Telegraph, November 4, 2020, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/11/04/man-forced-inform-fellow-uighurs-china-shot-turkey/ The UFWD’s Xinjiang bureau coerces individuals in Uyghur exile communities into spying on their neighbors by making threats against their families still living in the Uyghur homeland. This strategy is meant to both gather details about Uyghurs abroad and also discourage Uyghurs from speaking out against the Chinese state.60Alexander Bowe, “China’s Overseas United Front Work: Background and Implications for the United States,” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, August 24, 2018, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/China’s%20Overseas%20United%20Front%20Work%20-%20Background%20and%20Implications%20for%20US_final_0.pdf In 2009, Pakistani citizen Kamirdin Abdurahman, a Uyghur born in Pakistan, visited the Uyghur homeland. During his visit, Chinese authorities confiscated his passport and demanded that he spy on Uyghur activist networks in Rawalpindi. After sharing his story with the press back in Pakistan, Kamirdin received a series of threatening phone calls, which eventually caused him to flee into Afghanistan for fear of his life.61Siddiqui, “China Is Trying To Spy On Pakistan’s Uighurs.” Afghanistan has reportedly seen some novel approaches to this method of spy recruitment. For example, in December 2020 in Kabul, Indian media reported that Afghanistan’s intelligence agency,62“Afghanistan Arrests 10 Chinese Citizens on Charges of Espionage, asks China to Apologise,” Opindia, December 25, 2020, https://www.opindia.com/2020/12/afghanistan-arrests-10-chinese-citizens-charges-of-espionage-apologise/ the National Directorate of Security, had arrested ten Chinese nationals for allegedly trying to build an artificial Uyghur cell to attract supposed militant Uyghurs in Afghanistan that were of concern to China.63Aakriti Sharma, “‘China-Pakistan Spy Ring’ Busted in Afghanistan; 10 Chinese Nationals Held on Espionage Charges,” EurAsian Times, December 25, 2020, https://eurasiantimes.com/china-pakistan-spy-ring-busted-in-afghanistan-10-chinese-nationals-held-on-espionage-charge/

China also tries to instill fear and suspicion among Uyghur communities using networks of spies and informants to sever social ties […]

Afghanistan has reportedly seen some novel approaches to this method of spy recruitment. For example, in December 2020 in Kabul, Indian media reported that Afghanistan’s intelligence agency,64“Afghanistan Arrests 10 Chinese Citizens on Charges of Espionage, asks China to Apologise,” Opindia, December 25, 2020, https://www.opindia.com/2020/12/afghanistan-arrests-10-chinese-citizens-charges-of-espionage-apologise/ the National Directorate of Security, had arrested ten Chinese nationals for allegedly trying to build an artificial Uyghur cell to attract supposed militant Uyghurs in Afghanistan that were of concern to China.65Aakriti Sharma, “‘China-Pakistan Spy Ring’ Busted in Afghanistan; 10 Chinese Nationals Held on Espionage Charges,” EurAsian Times, December 25, 2020, https://eurasiantimes.com/china-pakistan-spy-ring-busted-in-afghanistan-10-chinese-nationals-held-on-espionage-charge/

Digital Surveillance

In Pakistan, Uyghurs face intense digital threats. China has used powerful spyware programs against Uyghurs there, creating malware to infect iPhones via WhatsApp messages. A recent study by digital security firm Lookout discovered that China had been installing spyware on Pakistani phones. The study showed how spyware made its way onto Uyghur smartphones through third-party apps found on local sites and advertisements (i.e., sites referencing country-specific services and news outlets).66Simon Chandler, “China Uses Android Malware to Spy on Ethnic Minorities Worldwide, New Reports Says,” Forbes, July 6, 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/simonchandler/2020/07/06/china-uses-android-malware-to-spy-on-ethnic-minorities-worldwide-new-research-says/ Phishing sites containing the spyware were found in ten different languages, including Urdu, Persian, Turkish, and Uyghur. Once downloaded, the spyware can collect a variety of personal data from smartphones, including text message history, contact information, location data, and even audio from phone conversations.67Ibid.

Coercion-by-Proxy

In order to effectively coerce Uyghurs beyond its borders, China relies on a variety of surrogate methods. When authoritarian states face resistance to their rule from opponents living abroad, they often resort to more indirect tactics, preying on these opponents’ relatives who live inside the authoritarian state.68Fiona Adamson, “At Home and Abroad: Coercion-by-Proxy as a Tool of Transnational Repression,” Freedom House, 2020, https://freedomhouse.org/report/special-report/2020/home-and-abroad-coercion-proxy-tool-transnational-repression The costs of targeting these individuals living in the home state are lower than targeting the opponents living abroad and can achieve the same result. The targeting of home-state relatives involves a range of more overt tactics, including imprisonment, violent attacks, and torture, along with less overt tactics, such as harassment, surveillance, and intimidation.69Edward Lemon, Saipira Furstenburg, and John Heathershaw, “Tajikistan: Placing Pressure on Political Exiles by Targeting Families,” Foreign Policy Center, December 4, 2017, https://fpc.org.uk/tajikistan-placing-pressure-political-exiles-targeting-relatives/ Due to the strength of the police state in the XUAR, many Uyghurs living abroad have been pressured to return home or cease their political activities abroad through their relatives. One Pakistani gemstone trader from Gilgit-Baltistan, who was married to a Uyghur woman, was denied entry into the XUAR unless he brought his wife with him. After the trader complied and returned to the border with his wife, XUAR authorities detained and later incarcerated her back in the Uyghur Region.70Khan, “Pakistani Husbands Distressed.” Similarly, a clothing merchant from Pakistan told a journalist from Deutsche Welle that his Uyghur wife was also detained, and even after she was released, Chinese authorities installed a monitoring device on her phone to track her calls to her family in Rawalpindi.71Ibid.

Extradition Treaties and Legal Agreements

China’s motivation to sign extradition treaties with countries like Pakistan has formed another vital tranche of its campaign of transnational repression. International extradition is defined as a practice of one country formally surrendering an individual alleged of a crime to another country with jurisdiction over the crime charged. The first such treaty between Pakistan and China was signed in 2003 after China accused Pakistan of secretly arresting Uyghur militants.72“Compendium of Bilateral and Regional Instruments for South Asia,” UNODC, 2015, https://www.unodc.org/documents/terrorism/Publications/SAARC%20compendium/SA_Compendium_Volume-2.pdf On December 15, 2003, the Chinese Ministry of Public Security shared its first list of “East Turkestan terrorists” and “terrorist organizations” abroad.73“China Names Six Uyghurs on Terror List,” BBC, April 6, 2012, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-17636262 The list named 11 individuals and four organizations, calling for international partners such as Pakistan to cooperate in arresting and deporting these individuals to China. China provided little to no evidence to corroborate the accusations it made against these individuals, according to Amnesty International.74Amnesty International, “People’s Republic of China Uighurs fleeing persecution.” Much of the “evidence” appeared to have been problematically extracted from individuals in the XUAR under torture or interrogation, a widespread practice in China that undermines the credibility of its accusations.75“Refugees Review Tribunal: CHN31261,” Australian Refugee Review Tribunal, February 9, 2007. Neighboring Afghanistan has never signed any formal extradition agreements with China, but in 2014, Afghan security forces detained and deported Uyghur activist Israel Ahmet under questionable circumstances.76Bethany Matta, “China to Neighbors: Send Us Your Uyghurs,” Al Jazeera, February 18, 2015, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2015/2/18/china-to-neighbours-send-us-your-uighurs

Multilateral Organizations

Finally, China has invested in the creation of its own web of international structures in order to pursue Uyghurs around the world. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), which Pakistan joined in 2017 after being an observer since 2005,77“Pakistan Joins the Security Bloc Led by China, Russia,” Dawn, June 10, 2017, https://www.dawn.com/news/1338647; “Pakistan Joins SCO as Observer,” Dawn, July 6, 2005, https://www.dawn.com/news/146634/pakistan-joins-sco-as-observer has been a particularly important vehicle for pursuing its goals of limiting Uyghur political activism abroad. The organization’s primary mandate is to fight the “three evils” of terrorism, extremism and separatism.78Aris, S. “The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation: ‘Tackling the Three Evils.’ A Regional Response to Non-Traditional Security Challenges or an Anti-Western Bloc?” Europe-Asia Studies 61, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27752254, p. 457–482. According to provisions agreed upon in 2005, the SCO requires all members to recognize terrorist, extremist, and separatists acts, regardless of whether the members’ own laws classified them as such.79“Concept of Cooperation of State Members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in Fight Against Terrorism, Separatism and Extremism,” Shanghai Cooperation Organization, July 5, 2005, https://cis-legislation.com/document.fwx?rgn=8218 Due to many member states having loose definitions of these terms, as well as Article 2 of the SCO’s 2009 Convention on Counter-terrorism simply defining terrorism as an “ideology of violence,” SCO member states are able to take advantage of these loose definitions to pursue political opponents abroad.

The SCO operates mainly through two administrative bodies: a Secretariat based in Beijing and the Regional Anti-Terrorism Structure (RATS). Established in January 2006, RATS is a consolidated list of extremist, terrorist, and separatist individuals and groups that would balloon to include 2,500 individuals and 769 groups by September 2016. According to Thomas Ambrosio, “the RATS serves as the central locus of the process of ‘sharing worst practices’ amongst the SCO member states.”80Thomas Ambrosio, “The legal framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization: An architecture of authoritarianism,” The Foreign Policy Centre, May 24, 2016, https://fpc.org.uk/sco-architecture-of-authoritarianism/ The European Court of Human Rights has described these norms as “an absolute negation of the rule of law.”81Amnesty International, “Return to Torture: Extradition, Forcible Returns and Removals to Central Asia,” July 3, 2013, 9, https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/EUR04/001/2013/en/ Several counter-terror drills under a series of “Peace Missions” have been staged under the RATS framework in Pakistan since 2018, strengthening Islamabad’s security cooperation with China.82“SCO Member States Including India to Participate in Anti Terror Drills in Pakistan,” The Express Tribune, March 22, 2021, https://tribune.com.pk/story/2290778/sco-member-states-including-india-to-participate-in-anti-terror-drills-in-pakistan

Outside the SCO, China established a new security mechanism in 2016 called the Quadrilateral Cooperation and Coordination Mechanism (QCCM), which is made up of Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. The organization is tasked with jointly combating terrorism and further advancing security cooperation between these states.83Joshua Kucera, “Afghanistan, China, Pakistan, Tajikistan Deepen ‘Anti-Terror’ Ties,” Eurasianet, August 4, 2016, https://eurasianet.org/afghanistan-china-pakistan-tajikistan-deepen-anti-terror-ties The chiefs of general staffs of the four military forces met in Ürümchi to announce QCCM in 2016, stating it would coordinate efforts on the “study and judgement of the counter-terrorism situation, confirmation of clues, intelligence sharing, anti-terrorist capability building, joint anti-terrorist training, and personnel training.”84Ibid. China combines its security coordination with these countries by pledging large development projects as part of the BRI, and vice-versa.

In a 2020 report to the U.S. Congress, the Pentagon highlighted how China’s security and development interests are complementary and described how China was seeking new ways to increase its power projection in Central and South Asia. The Pentagon report also detailed how the Chinese military was planning to build “military logistics facilities” in several countries including Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan in order to better protect China’s economic and security interests.85U.S. Department of Defense, “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” September 1, 2020, https://media.defense.gov/2020/Sep/01/2002488689/-1/-1/1/2020-DOD-CHINA-MILITARY-POWER-REPORT-FINAL.PDF These developments have dire consequences for Uyghurs living in these border regions. In June 2021, lawyers submitting evidence to the International Criminal Court (ICC) on behalf of a Uyghur organization alleging that the Chinese government has committed various forms of transnational repression of Uyghurs in Tajikistan said that “the number of Uyghurs living in Tajikistan has been reduced from 3,000 to 100 in the past 15 years, with most of the reduction happening in 2016–2018.”86Stephanie van den Berg, “Lawyers urge ICC to probe alleged forced deportations of Uyghurs from Tajikistan,” Associated Press, June 10, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/lawyers-urge-icc-probe-alleged-forced-deportations-uyghurs-tajikistan-2021-06-10/ In 2019, observers alleged that Tajikistan rendered three Uyghurs to China on behalf of the Turkish government.87“Uyghur Mother, Daughter, Deported to China From Russia,” Radio Free Asia, August 9, 2019, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/deportation-08092019171834.html

Leaked internal CCP documents obtained by the New York Times in 2019 provide further evidence of how China’s leadership has increasingly fixated on securitizing the Uyghur homeland. Set against a backdrop of the 2009 unrest in Ürümchi and the looming specter of a U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, the leaked documents reveal how Xi Jinping pushed for a new strategy of expanding China’s security apparatus in the XUAR and Central and South Asia. In closed-door speeches included in these documents, Xi states that economic development “does not automatically bring lasting order and security” and that China would have to wage a “People’s War” in the region by emulating the U.S.-led Global War on Terror.88Austin Ramzy and Chris Buckley, “‘Absolutely no Mercy’: Leaked Files Expose How China Manages Mass Detention of Muslims,” New York Times, November 16, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/11/16/world/asia/china-xinjiang-documents.html Xi’s speeches signaled that moving forward, Chinese strategy in Central and South Asia would have to integrate traditional economic development projects with new military and security systems.

VII. China’s Historical Engagement with Pakistan

Often dubbed the “eighth wonder of the world,” the Karakoram Highway is a powerful symbol of Pakistan’s troubled relationship with China, a dynamic so complex that CCP officials have often joked that Pakistan is to China as Israel is to the United States.89Thalif Deen, “China: ‘Pakistan is our Israel,’” Al Jazeera, October 28, 2010, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2010/10/28/china-pakistan-is-our-israel Despite the highway’s glowing promises of regional connectivity, commercial activity on the highway remains low even to this day.90Syed Irfan Raza, “Karakoram Highway Inadequate for CPEC Traffic, Says Senate Panel,” Dawn, November 7, 2016, https://www.dawn.com/news/1294813 The highway does, however, fulfill an important strategic function. Following its completion, the highway allowed Pakistan and China to establish a military foothold in mountainous landscapes claimed by India. In 1966, the same year the highway was announced, China and Pakistan signed their first military agreement, which was worth $120 million USD, and soon after came a flurry of trade agreements to stimulate trade between Pakistan and the XUAR.91“Today’s Karakoram Highway Follows the Ancient Silk Route From China,” Pakistan Affairs, United States: Information Division, Embassy of Pakistan., 1977. Rapidly shifting geopolitics brought the two countries closer, with Moscow’s 1979 decision to invade Afghanistan raising fears in China of a military buildup by its Cold War rival on its sensitive western borders. Faced with a shared interest in driving the Soviet Union out of South Asia, an unlikely alliance between Pakistan, China, Saudi Arabia, and the United States emerged to funnel money, weapons, and logistical support to the Islamist mujahideen fighters defying the Soviet military. Some 30,000 fighters assembled from across the Muslim world to pass through Pakistan and onward into the conflict across the border.92G. Parthasarathy, “Challenges in Afghanistan,” The Tribune, October 15, 2020, https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/comment/challenges-in-afghanistan-155896

In 1983, China gave Pakistan completed designs for nuclear weapons and assisted Islamabad’s scientists to enrich weapons-grade uranium and conduct missile tests in the XUAR’s Lop Nor nuclear facilities.

Relations throughout the Soviet-Afghan War brought China and Pakistan only closer. In 1983, China gave Pakistan completed designs for nuclear weapons and assisted Islamabad’s scientists to enrich weapons-grade uranium and conduct missile tests in the XUAR’s Lop Nor nuclear facilities.93Andrew Small, The China-Pakistan axis: Asia’s new geopolitics, (London: Hurst, 2015), p. 42. By 1986, the two signed an official nuclear cooperation deal, promising a series of technology transfers and financial commitments. This cooperation continued throughout the 1990s with China building a new 300-megawatt nuclear power plant in Pakistan in 1991.94Raza, “Karakoram Highway Inadequate for CPEC Traffic.”

China: A Source of Stability?

Over the last two decades, both sides have framed the Sino-Pakistan relationship as being of mutual benefit and a source of stability, security, and economic development for Pakistan. In 2013, former Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and Xi Jinping marked their simultaneous ascension to leadership with a large display of ceremony and friendship in Islamabad. Sharif noted “critical changes” and “major developments” within China and the region as a whole and proclaimed that Xi Jinping would usher in a new era of development for Pakistan.95Mateen Haider, “Economic corridor in focus as Pakistan, China sign 51 MoUs,” Dawn, April 20, 2015, https://www.dawn.com/news/1177109 Once Imran Khan was elected to leadership in 2018, he generally continued to heap praise on China’s development efforts. Winning the election on a promise of a Naya Pakistan (New Pakistan), Khan gave specific praise to China’s anti-corruption efforts, hoping to put 500 corrupt people in jail as Xi Jinping had done in China.96Tariq Butt, “Imran all praise for China’s efforts against corruption,” Gulf Today, October 8, 2019, https://www.gulftoday.ae/news/2019/10/08/imran-all-praise-for-chinas–efforts-against-corruption

Once Imran Khan was elected to leadership in 2018, he generally continued to heap praise on China’s development efforts.

Much of China’s rhetoric and strategy for expanding its presence in Pakistan focuses on the Gwadar Port, which former Pakistani President Musharraf hailed as the “economic funnel of (Central and South Asia)” in 2002, anticipating the BRI, which Xi Jinping would go on to announce in Kazakhstan over a decade later.97“President Xi Jinping Delivers Important Speech and Proposes to Build a Silk Road Economic Belt with Central Asian Countries,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, September 7, 2013, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/topics_665678/xjpfwzysiesgjtfhshzzfh_665686/t1076334.shtml Signed into existence by newly elected Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif in 2013, the CPEC deal outlined an ambitious $46 billion USD Gwadar Port development project over a 15-year timeframe.98“Common Vision for Deepening China-Pakistan Strategic Cooperative Partnership in the New Era,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, July 5, 2013, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665385/2649_665393/t1056958.shtml Envisioned as a Pakistani Dubai, the Gwadar Port and CPEC would serve two ideal functions for Pakistan: they would bring more commerce to Pakistan, and they would help Islamabad gain more control over the resource-rich but restive Balochistan province. For China, the projects would demonstrate to the world Beijing’s ability to bring stability to a region rife with turmoil, while extending its reach into the Arabian Sea. For both countries, however, the projects have fallen far short of expectations. Opened for commercial shipments in 2008, the Gwadar Port has seen only a meager amount of traffic, receiving its first container ship only in 2018.99“Under CPEC: First container vessel anchors at Gwadar,” The Express Tribune, March 8, 2018, https://tribune.com.pk/story/1653969/cpec-first-container-vessel-anchors-gwadar The port’s local benefits are also questionable. If the port becomes profitable, China will receive the lion’s share of revenue at 91%, and Pakistan’s federal government will receive just 9%, leaving nothing for Balochistan’s provincial government.

In his book The Emperor’s New Road, political analyst John Hillman notes that much like the United States before it, China largely overestimates its capacity to induce reform within Pakistani politics.100Jonathan E. Hillman, The Emperor’s New Road: China and the Project of the Century, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), p. 149. With low regulatory standards and a distinct lack of conditionality when compared with Western loans, Chinese money has often been privy to the demands of local corruption. Chinese state-owned enterprises often bypass local bureaucratic approval and traditional bidding processes to secure project approval, lining the pockets of Chinese actors and local elites.101Audrye Wong, “How Not to Win Allies and Influence Geopolitics,” Foreign Affairs, April 4, 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2021-04-20/how-not-win-allies-and-influence-geopolitics Though CPEC was cause for celebration for Pakistan’s domestic industries, private and even state entities have had a hard time securing contracts for the various connected infrastructure projects, owing to competition with Pakistan’s large military industry conglomerates. For example, in 2018, a civilian affiliated company received a $280 million USD CPEC contract to build an oil pipeline, but a year later the contract transferred to the military-run Frontier Works Organization. The conglomerate received the contract, and the price tag also shot up to $370 million USD for the same output.102Hoo Tiang Boon and Glenn K. H. Ong, “Military Dominance in Pakistan and China-Pakistan Relations,” Australian Journal of International Affairs 75 (2021): 88. Local politics have also caused considerable issues for Beijing. In 2017, China agreed to help finance the Diamer Bhasha Dam in Gilgit-Baltistan—a project that cost $14 billion USD to construct and faced numerous delays in the process. Additionally, land disputes with local residents persist, and delayed payments to those displaced by the project have sparked protests.103Jamil Nagri, “GB Government Demands Action on Court Orders for its Rights,” Dawn, October 19, 2018, https://www.dawn.com/news/1439851

Leaders in Pakistan have consistently spoken about CPEC in messianic terms, claiming that it will solve all of Pakistan’s economic problems, fix its energy shortages, and boost the country’s manufacturing and export industries. But Pakistani politicians have also used CPEC negotiations for short-term political gains, often at the cost of long-term benefits for the country. Facing reelection in 2018, Sharif pushed for more Chinese-backed power plants to help with chronic energy shortages across the country. To entice Chinese investment, Sharif guaranteed large yearly returns by Pakistan’s government, with some reports putting the figure as high as 34% guaranteed returns for 30 years.104Jeremy Page and Saeed Shah, “China’s Global Building Spree Runs into Trouble in Pakistan,” Wall Street Journal, July 22, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-global-building-spree-runs-into-trouble-in-pakistan-1532280460 As a result of these negotiations, Beijing played a larger role in Pakistan’s energy-production sector. Since the approval of new energy facilities in Pakistan under CPEC, Chinese energy projects and Chinese power companies have contributed to hundreds of millions of dollars in contract violations and financial transgressions. Instances of graft among these energy production groups included inflated set-up costs, annual profits that quadruple the limit set by Pakistani regulations, and Chinese firms that over-quote tariff charges, all of which have directly led to spikes in energy bills for Pakistanis and massive debt for the government.105Waishali Basu Sharma, “As Pakistan’s Energy Crisis Worsens, Have Chinese Investments Failed Islamabad?” The Wire, June 2, 2020, https://thewire.in/south-asia/pakistan-energy-crisis-cpec Khan’s government has been unable to make any significant policy changes to CPEC, while allowing Pakistan’s debt crisis to grow. By the end of the 2019–20 fiscal year, debt reached over 87% of Pakistan’s GDP, up from 72% of GDP the previous year. Pakistan’s total debt and liabilities rose 7% from $106.3 billion USD in 2019 to $113.8 billion USD in 2020.106Waishali Basu Sharma, “Pakistan Debt Intensifies as Economic Mismanagement Continues Unabated,” The Wire, February 27, 2021, https://thewire.in/south-asia/pakistan-debt-crisis-intensifies-as-economic-mismanagement-continues-unabated Though Pakistan has taken on increasing debt from China under CPEC, everyday costs like fuel and electricity continue to rise, meaning that Pakistanis have seen very little benefit from this debt.

In addition to inflating its rhetoric on the economic advantages of the partnership, China has also proven itself to be a potentially destabilizing security partner for Islamabad. The 2007 Siege of Lal Masjid, the Red Mosque, in Islamabad demonstrates this risk. The mosque had long been a hub of radical Islamic activity, but in 2007, conservative vigilantes from Lal Masjid entered a massage parlor in sector F-8, one of the city’s wealthiest neighborhoods, and dragged six Chinese women kicking and screaming from the building, accusing them of prostitution.107Farhan Bokhari, “Women Kidnapped From Alleged Brothel,” CBS News, June 23, 2007, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/women-kidnapped-from-alleged-brothel/ From June 25 to 28 of that year, Federal Interior Minister Aftab Ahmad Khan Sherpao traveled to Beijing for discussions on bilateral cooperation against terrorism.108“China Urges Pakistan to Ensure Security of Chinese After Hostage Issue,” Xinhua News Agency, June 27, 2007, http://en.people.cn/200706/27/eng20070627_387969.html When he returned to Islamabad, Sherpao reported that his Chinese counterparts were falsely attributing the raid on the Chinese massage parlor to Uyghur students studying at the Lal Masjid madrassa and expressed concern that Uyghur terrorists associated with the East Turkestan Islamic Movement/Turkestan Islamic Party (ETIM/TIP) in Pakistan may pose a threat to the 2008 Olympic Games. China accused Islamabad not only of negligence over the security of Chinese nationals but also of harboring so-called enemies of the Chinese state. Fearing Chinese retaliation, Musharraf chose to demonstrate a strong hand, launching “Operation Silence,” a violent eight-day siege on the mosque. In the end, at least 103 people were killed, including women and children, with some accounts putting the massacre at some several hundred.109“The aftershocks,” Jang, July 7, 2010, https://jang.com.pk/thenews/jul2010-weekly/nos-04-07-2010/spr.htm Of the 15 non-Afghan foreigners killed, 12 were reportedly Uyghurs.110“Pakistan Bombings Raise Fears of Taliban, al Qaeda Resurgence,” CNN, July 16, 2007, https://edition.cnn.com/2007/WORLD/asiapcf/07/16/pakistan.alqaeda/index.html; Ravi Shekhar Narain Singh, “The Military Factor in Pakistan,” (Frankfort, 2008), p. 426. In 2008, Amnesty International labeled the killings by Pakistani security forces as an “excessive use of force.”111Amnesty International, “Amnesty International Report 2008: Pakistan,” May 28, 2008, https://www.refworld.org/docid/483e27a656.html

As Andrew Small highlights, the siege unleashed an array of new political forces across the country, bringing Pakistan to the brink of chaos and making highly visible development projects a new target for attack.112Small, The China-Pakistan Axis, p. 88–89. A large number of militant groups in the country’s tribal areas annulled their peace agreement with the Pakistani government and consolidated themselves under a new umbrella organization: the Tehrik-i-Taliban-Pakistan (TTP), also known as the Pakistani Taliban. In less than two years, they went on to occupy territory within 60 miles of Islamabad. Their influence spread so rapidly that the Pakistani military deployed soldiers to protect the Karakoram Highway, which the authorities feared was under threat.113“Troops Deployed Along Karakoram Highway,” Dawn, April 28, 2009, https://www.dawn.com/news/889019/troops-deployed-along-karakoram-highway

As China has grown more active in the internal politics of neighboring states like Pakistan, it has disrupted internal balances of power, creating the very conditions in which anti-Chinese sentiments can grow and thrive. As China’s policies in the XUAR and elsewhere have grown harsher, the country’s treatment of Uyghurs has produced growing animosity toward China from disparate Islamic militant groups.114Matta, “China to Neighbors: Send Us Your Uyghurs.” In November 2014, for example, the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan Jamaat-ul Ahrar—a branch of the Pakistani Taliban—printed an article in its official magazine that said, “We’re warning Beijing to stop killing Uyghurs. If you don’t change your anti-Muslim policies, soon the mujahideen will target you.”115Ibid. Pakistan’s minority groups, most prominently the Balochi, deeply mistrust Chinese development projects. Locals fear that they will not reap any rewards from these development projects and that the projects are designed by the Pakistani state, in collaboration with China, to fundamentally shift the demographics of given regions.116Muhammad Akbar Notezai, “Why Balochs Are Targeting China,” The Diplomat, November 26, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/11/why-balochs-are-targeting-china/

Pakistan’s Uyghur Community

For most of the long history of Sino-Pakistani relations, authorities left the Uyghur community in Pakistan relatively undisturbed. That would all change after 1990, with an uprising in the XUAR town of Baren that year and the emergence of the independent republics in Central Asia following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.117Gardner Bovingdon, The Uyghurs: Strangers in Their Own Land, 2010, p.125. Although there is no official estimate, anthropological research suggests that there are roughly 300 Uyghur families currently residing in Pakistan, two-thirds of whom live in Rawalpindi, with additional clusters in Gilgit-Baltistan, Lahore, Karachi, and Peshawar.118Alessandro Rippa, “From Uyghurs to Kashgaris (and Back?): Migration and Cross-border Interactions Between Xinjiang and Pakistan,” Crossroads Asia Working Paper Series, no. 23 (2014): 7. From his interviews with Uyghur communities in the country, anthropologist Alessandro Rippa has argued that most of these families arrived from the XUAR beginning in 1948 to flee the invading People’s Liberation Army (PLA), with additional refugees flowing into Pakistan in the wake of political unrest in the XUAR towns of Baren (1990); Ghulja (1997); and Ürümchi (2009). Many others over the decades simply left the XUAR to go on hajj, settled in Pakistan, and never returned to their homeland.119Ibid.

Though officially completed in 1978, the Karakoram Highway was not open for civilian use until 1982.120Kreutzmann, Hermann, “The Karakoram Highway: The Impact of Road Construction on Mountain Societies,” Modern Asian Studies 25 (1991): 725. The opening of the highway to civilians coincided with Deng Xiaoping’s Reform and Opening program, allowing a shift in China to more tolerant policies, which led to a turning point in Uyghur cultural and religious life. As more mosques and madrassas opened, many Uyghurs took advantage of the policy shift to go on hajj, which was allowed to resume in 1979 after a 15-year suspension.121Shichor, Yitzhak, “Blow Up: Internal and External Challenges of Uyghur Separatism and Islamic Radicalism to Chinese Rule in Xinjiang,” Asian Affairs: An American Review Vol. 32 (2005): 122; Edmund Waite, “The impact of the State on Islam Amongst the Uyghurs: Religious Knowledge and Authority in the Kashgar Oasis,” Central Asian Survey 25 no. 3 (2006): 254-5. Pakistan would serve as the key transit country for these Muslims conducting hajj, with around 1,200 pilgrims crossing into Pakistan on their way to Mecca in 1985. To help fund the new pilgrims from their homeland, Uyghur traders emerged to sell goods and materials, particularly in Islamabad’s twin city of Rawalpindi.122Rippa, “From Uyghurs to Kashgaris (and Back?), 7. Wealthy Uyghurs from Saudi Arabia even donated two houses in Rawalpindi—named Khotan House and Kashgar House—which served as free temporary housing for Uyghur pilgrims on their way to Mecca.123Ibid. According to fieldwork by Alessandro Rippa, Kashgar House and Khotan House shuttered after 20 years and presently serve as warehouses for Uyghur traders.124Ibid.