A Uyghur Human Rights Project report by Bradley Jardine, Natalie Hall, and Louisa Greve. Read our press statement on the report here; download the full report here; and view a printable, one-page summary of the report here.

I. Executive Summary

The Chinese Party-state’s human rights atrocity crimes in the Uyghur region have caused a secondary humanitarian crisis among Uyghur diaspora communities worldwide. Since 2017, China’s mass incarceration of Turkic peoples in the Uyghur region has affected Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and Kyrgyz worldwide, leaving many destitute and traumatized as their family members, including the primary providers, are interred in concentration camps. The Chinese state actively interferes with the ability of Uyghur exiles to meet their basic humanitarian needs, often with the help of foreign governments, subjecting them to harassment, intimidation, surveillance, enforced statelessness, family separation, and community and cultural trauma.

While many governments are guilty of transnational rights violations, including advanced democracies,1Colleen Barry, “Ex-CIA Agent Convicted in Kidnap Skips Italian Justice,” AP News, October 29, 2019, https://apnews.com/article/b22a5ec9711645c291404073e7113524 China has harassed and pursued dissidents overseas on an unprecedented scale — particularly among Uyghur communities. Collectively, the Chinese government’s strategies have created trauma, economic dislocation, and familial separation wherever deployed. The Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP) and its partner, the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs, have documented this extraterritorial pursuit of Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples around the world in a series of five reports shedding light on the scope of this campaign since 2017.2See https://uhrp.org/transnational-repression and “Repression Across Borders: The CCP’s Illegal Harassment and Coercion of Uyghur Americans,” Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP), August 28, 2019, https://uhrp.org/report/repression-across-borders-the-ccps-illegal-harassment-and-coercion-of-uyghur-americans/; Bradley Jardine, Edward Lemon, and Natalie Hall, “No Space Left to Run: China’s Transnational Repression of Uyghurs,” UHRP and Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs, June 24, 2021, https://uhrp.org/report/no-space-left-to-run-chinas-transnational-repression-of-uyghurs/; Bradley Jardine and Robert Evans, “‘Nets Cast from the Earth to the Sky’: China’s Hunt for Pakistan’s Uyghurs,” UHRP and Oxus Society, August 11, 2021, https://uhrp.org/report/nets-cast-from-the-earth-to-the-sky-chinas-hunt-for-pakistans-uyghurs/; Natalie Hall and Bradley Jardine, “‘Your Family Will Suffer’: How China Is Hacking, Surveilling, and Intimidating Uyghurs in Liberal Democracies,” UHRP and Oxus Society, November 10, 2021, https://uhrp.org/report/your-family-will-suffer-how-china-is-hacking-surveilling-and-intimidating-uyghurs-in-liberal-democracies/; Bradley Jardine and Lucille Greer, “ Beyond Silence: Collaboration Between Arab States and China in the Transnational Repression of Uyghurs,” UHRP and Oxus Society, March 24, 2022, https://uhrp.org/report/beyond-silence-collaboration-between-arab-states-and-china-in-the-transnational-repression-of-uyghurs/

This report examines the humanitarian needs of Uyghur and other Turkic diaspora groups in the United States, Turkey, and post-Soviet Central Asia, where large communities remain, and highlights measures that the diaspora is taking to support itself in response to transnational repression, and identifies those areas where more help is needed. The study incorporates and builds on previous UHRP reports on the humanitarian crisis outside China caused by the atrocity crimes in the Uyghur region, as well as our extensive Transnational Repression of Uyghurs Database.3See Appendix 3.

II. Key Takeaways

- A secondary humanitarian crisis is unfolding in the Uyghur diaspora and exile communities abroad. Uyghurs living outside the Uyghur region face challenges including enforced statelessness and vulnerability to refoulement, loss of livelihoods and businesses, denial of access to healthcare and schools, single-parent families without a primary provider, homelessness, unaccompanied minors, collective trauma, cultural trauma, and ongoing harassment, threats, and cyberattacks.

- Uyghur diaspora civil society organizations (CSOs) have worked to meet the needs of Uyghur diaspora communities, offering skills training and support for home-based employment; scholarships for students; cash support for housing, food, clothing, and medical care; and social support through mutual aid programs, cultural programming, and mental health programming.

- While these organizations have had some success, their reach and ability to meet the needs of Uyghurs in diaspora communities are limited by a lack of resources for providing material humanitarian aid. Community and generational trauma have hardly been addressed due to stigma, cultural barriers, and limited access to healthcare.

III. Recommendations

- Academia: Uyghur students, scholars, writers, and artists should be supported through scholarships, fellowships, and research grants.

- Cultural organizations: create fellowships and grants for performers and writers.

- National governments: investigate and enforce domestic law to protect Uyghur citizens and asylum seekers from harassment, threats, coercion, and reprisals by Chinese security agencies; publicly affirm a policy of never deporting Uyghur refugees and asylum seekers to China; expedite Uyghur political asylum and refugee applications; prioritize humanitarian acceptance of stateless and at-risk Uyghur refugees currently exposed to reprisals or deportation in third countries.

- Donor organizations, including government agencies: support for livelihood and small-business programming; hunger and homelessness relief; healthcare programs; funding for Uyghur NGOs that seek to document ongoing human rights violations in the Uyghur region; funding for the creation of a secure, legally admissible database of evidence that could be used to hold the perpetrators of the human rights violations in the Uyghur region and resulting humanitarian crisis accountable; convening closed-door meetings for researchers to present their evidence on the perpetrators of the human rights violations in the Uyghur region and the resulting humanitarian crisis to other governments.

IV. Introduction

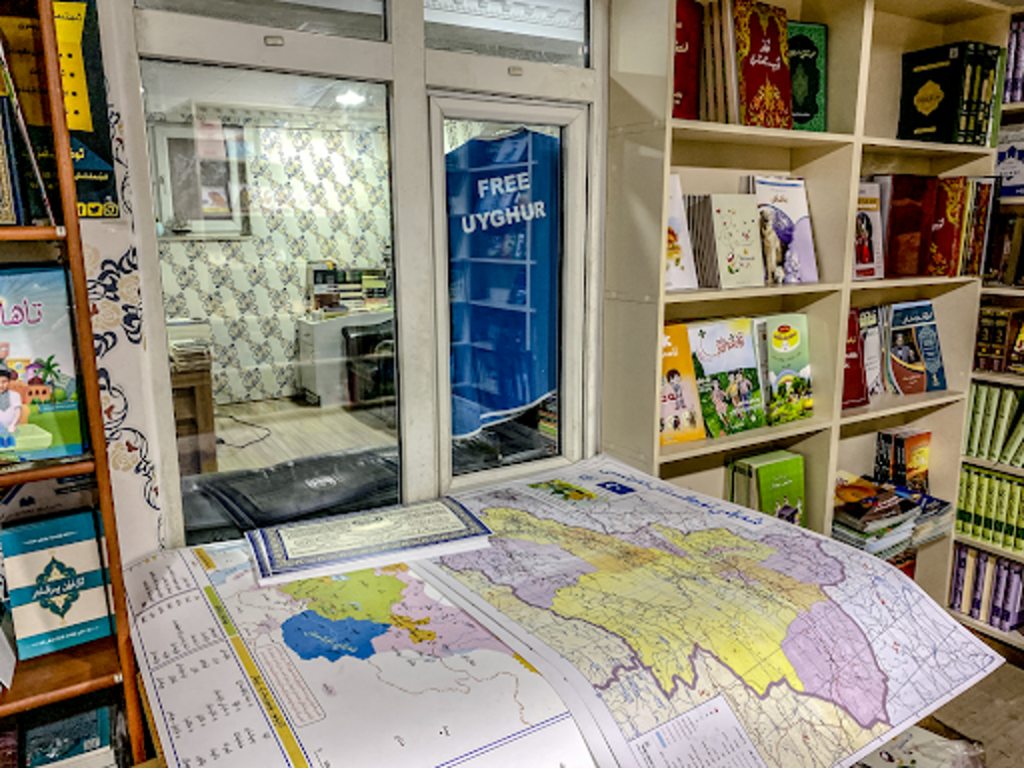

On the outskirts of Istanbul there is an orphanage for children whose parents have been detained in the Uyghur region’s camps. Turkey is one of 26 countries on a list used by Xinjiang authorities to detain Uyghurs on the grounds of contact with potential “terrorist” entities abroad. Around the city’s Zeytinburnu and Sefakoy districts, many individuals we met who ran independent Uyghur language bookstores, restaurants, and childcare facilities informed us they had been contacted by Chinese police who reminded them that if they ever stray into activism, their families in the Uyghur region may suffer consequences.

Uyghur targets of transnational repression include those who support human rights and democracy in their former homeland and those who advocate for the well-being of the families and loved ones they have left behind. Even ordinary diaspora members leading quiet lives have been targeted, demonstrating the extraordinary scope and intensity of the Chinese government’s efforts to impose collective punishment and repression across national borders.

Exile and diaspora communities must contend with many challenges to their day-to-day lives caused by this transnational repression. First, Uyghur refugees are often denied the right to valid documentation, resulting in enforced statelessness. As a result, many Uyghurs cannot legally work in their host countries, with some Uyghurs being unable to care for themselves and their family members, even becoming homeless in some instances. Further, many Uyghur children cannot attend school in their host countries without documentation. Second, Uyghurs must also withstand sophisticated digital campaigns designed to surveil and harass them, putting their families in danger and compromising their personal information and emotional well-being. Third, Uyghur families are separated; when spouses or parents disappear into the camps in the Uyghur region, many children are left in diaspora communities without documentation, means of support, and in some cases, an adult caretaker. Fourth, Uyghurs experience collective trauma due to the ongoing genocide, causing daily emotional distress. Finally, due to the loss of their families, their homeland, and the mass roundup of prominent Uyghur intellectuals, Uyghurs face the loss of their community, culture, and identity.

The report first examines the vulnerabilities of these diaspora communities and the challenges they face. This section is broken down into two parts, documenting the legal and technological factors responsible for the humanitarian vulnerabilities, as well as the types and scope of economic and psychosocial needs. The report then examines the efforts of Uyghur and Kazakh CSOs, and other international organizations and fundraising initiatives, to meet these needs, specifically looking at where these efforts have been successful and where they require more support, particularly where Uyghur diaspora members lack legal documentation. The report then makes recommendations for how critical stakeholders can respond to the humanitarian needs of the Uyghur and other Turkic diasporas.

V. Methodology

This report provides primary data from two sets of interviews conducted in August and September 2022. (1) Community-member interviews [6 in total] provide case studies of the humanitarian needs of Uyghur refugees and diaspora members currently living in the U.S., Turkey, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. (2) Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) with NGO and CSO leaders [12 in total] provide information on existing programs and descriptions of unmet needs.4We selected interviewees based on their expertise working with Uyghur communities in each target country, professional involvement in key events recounted in this independent analysis, and knowledge of China’s international policies. These KII interviews provide us with on-the-ground information about the ongoing efforts of Uyghur civil society organizations in the U.S., Turkey, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan, to meet the needs of their communities and the ongoing challenges they face. They also informed us about the larger civil society context in which the repression occurred. The report also draws on survey data on the mental trauma suffered by individuals in diaspora communities, perceptions of cyber threats, and a research database built by UHRP in partnership with the Oxus Society, the China’s Transnational Repression of Uyghurs Database.5See Appendix 1.

This report also references secondary sources in English, Chinese, Uyghur, Turkish, Kazakh, and Russian, including online interviews and personal accounts by Uyghurs experiencing various forms of humanitarian crisis and transnational repression, as well as writing in traditional print, digital, broadcast, social media, and government documents. We have used these primary and secondary sources to build a detailed overview of the humanitarian needs of the Uyghur diaspora and other Turkic peoples outside China affected by the atrocity crimes.

VI. Protecting the Uyghur Diaspora: Current Challenges

This study provides an overview of the humanitarian needs of diaspora and refugee Uyghurs, as well as Kazakhs and Kyrgyz affected by the genocide, in four countries: the U.S., Turkey, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan, to better understand the needs of Uyghur civil society in diverse socio-political contexts. Exiles and members of the Uyghur diaspora living in these countries have been subjected to extreme forms of transnational repression, which impact their humanitarian needs, including on their wellbeing and livelihoods.

| Country | Estimated Uyghur population |

| Kazakhstan | 300,0006Sean Roberts and Dana Rice, “Kazakhstan’s Ambiguous Position Towards the Uyghur Cultural Genocide in Xinjiang,” ASAN Forum, October 23, 2020, https://theasanforum.org/kazakhstans-ambiguous-position-towards-the-uyghur-cultural-genocide-in-china/ |

| Kyrgyzstan | 50,000 |

| Turkey | 50,000–60,000 |

| United States | 10,000–15,0007“Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over: 2009-2013,” U.S. Census Bureau, accessed September 28, 2022, https://www.census. gov/data/tables/2013/demo/2009-2013-lang-tables.html |

The global threat to human rights presented by the Chinese Party-state requires a global response. Lasting humanitarian aid for exiles and diasporas depends on governments to fortify their domestic protections as well as on coordinated, multilateral campaigns to provide immediate aid to victims and survivors of the genocide, and to pro-actively counter transnational repression.

The United States

The U.S. government has condemned the Chinese government’s crimes against humanity in the Uyghur region and implemented legislative and diplomatic measures to hold the Chinese government accountable for its human rights abuses. In June 2020, the U.S. Congress passed the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act, which mandated sanctions on officials and entities violating the human rights and religious freedoms of Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples in the Uyghur region. Since then, the U.S. government has placed sanctions on 33 Chinese officials and government agencies, as well as banning imports and/or exports from more than 50 Chinese companies.8Marco Rubio, “S.3744 – 116th Congress (2019–2020): Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act of 2020,” legislation, June 17, 2020, 2019/2020, http://www.congress.gov/; see also: “U.S. Sanctions List – Uyghur Human Rights Project,” https://uhrp.org/sanctions/ In January 2021, then-Secretary of State Michael Pompeo determined that the Chinese government was committing ongoing crimes against humanity and genocide in the Uyghur region.9“Determination of the Secretary of State on Atrocities in Xinjiang,” United States Department of State (blog), January 19, 2021, https://2017-2021.state.gov/determination-of-the-secretary-of-state-on-atrocities-in-xinjiang/ Shortly after taking office, Secretary of State Antony Blinken confirmed his predecessor’s determination.10Colm Quinn, “Blinken Names and Shames Human Rights Abusers,” Foreign Policy, March 31, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/03/31/blinken-uyghur-china-human-rights-report/ In December 2021, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution condemning China’s human rights violations as genocide, and called on the U.S. government and UN Security Council to take further action. Most recently, President Joe Biden signed the Uyghur Forced Labor Protection Act into law in December 2021; the law, which steps up enforcement of U.S. prohibitions on the import of goods produced using forced labor with regard to goods sourced from the Uyghur region, came into effect in June 2022.11James P. McGovern, “H.R.6210 – 116th Congress (2019–2020): Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act,” September 23, 2020, 11, 2019/2020, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/6210

While the Biden Administration has promised to increase refugee resettlement, only 11,400 refugees were admitted in 2021. None of those admitted were Uyghurs.

However, despite the dire needs of the Uyghur diaspora community, the U.S. has not instituted any programs for humanitarian aid and has admitted very few Uyghurs through the U.S. refugee resettlement program. Further, the U.S. sharply reduced the number of refugees it would accept under President Donald Trump: in 2017, the U.S. accepted 85,000 people; by the end of 2020, that number had decreased to 11,800. While the Biden Administration has promised to increase refugee resettlement, only 11,400 refugees were admitted in 2021. None of those admitted were Uyghurs.12Jasmine Aguilera, “The U.S. Admitted Zero Uyghur Refugees Last Year. Here’s Why,” Time, October 29, 2021, https://time.com/6111315/uyghur-refugees-china-biden/

Uyghurs living in the diaspora community in the U.S. face challenges as well: many of those who have applied for asylum status in the U.S. are spending years in legal limbo, waiting for the results of their asylum cases. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) has an unprecedented backlog of cases, which has only grown during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to research in progress (publication forthcoming) by Dr. Henryk Szadziewski, director of research at UHRP, Uyghurs living in the U.S. were impacted by both Trump Administration policies on immigration, as well as COVID-19, and have experienced up to a five-year delay in asylum and other immigration processes. Many Uyghurs struggle with how poorly these delays have been communicated to them, leaving many to wonder about the status of their cases.13Bradley Jardine, interview with Dr. Henryk Szadziewski, audio, September 29, 2022. The Uyghur American Association (UAA) has assisted many asylum seekers, particularly in guiding them through the procedures for requesting expedited interview scheduling and providing interpretation and translation. However, UAA’s capacity is limited. Further, many Uyghurs are fearful of Chinese government retaliation and choose to avoid any contact with UAA.14Bradley Jardine, interview with Elfidar Iltebir, audio, September 19, 2022. As a result, there remains a large gap in communication and access to assistance with asylum and visa issues.

The U.S. government has taken law enforcement and legislative steps to prevent transnational repression within the U.S. For example, in early 2022, the FBI launched a website to explain transnational repression and how to report incidents for investigation. The FBI also published an intelligence bulletin in August 2021 that sought to inform the Uyghur community of attempted transnational repression by the Chinese government. In July 2021, Congress passed the Transnational Repression Accountability and Prevention (TRAP) Act, which seeks to counter the abuse of Interpol by authoritarian states and leverage American financial support for the institution.15Steve Cohen, “Text: H.R.4806 – 117th Congress (2021–2022): TRAP Act of 2021,” legislation, July 29, 2021, 2021/2022, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/4806/text However, Uyghurs are still highly vulnerable to the long reach of the Chinese government in the U.S. One Uyghur living in Arlington, Virginia, wanted to protest at a courthouse near his home about the lengthy asylum bureaucratic process for legal status in the U.S. that Uyghurs face, but expressed concern about being in the public eye; he had already received threatening Telegram messages after starting his asylum process.16Bradley Jardine, interview with Dr. Henryk Szadziewski.

While evidence suggests some movement for Uyghurs within the U.S. immigration system starting in 2022, there is work to be done, with many applications for asylum outstanding. Further, the psychosocial needs of Uyghur communities in the U.S. have gone largely ignored; instead, they have organized to meet these needs independently.

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan’s government has taken a nuanced approach in its efforts to balance its interests in protecting its citizens with the importance of its economic and political relationship with Beijing. Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) is critical to Kazakhstan’s economic well-being, with Chinese state-owned enterprises investing billions of dollars into Kazakhstan’s energy and oil sector and infrastructure.17Reid Standish, “What Kazakhstan’s Crisis Means For China,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, January 9, 2022, https://www.rferl.org/a/kazakhstan-crisis-china-xi-toqaev/3164620 8.html Kazakhstan is home to large Uyghur communities, and some ethnic Kazakhs who have both Kazakh and Chinese citizenship in contravention of Chinese and Kazakh laws. Kazakhs in the Uyghur region are being imprisoned alongside Uyghurs – a fact many Kazakh CSOs have sought to draw attention to. As a result of this complicated relationship, Kazakhstan has positioned itself as largely neutral in the face of the Chinese state’s human rights violations. This neutrality has taken many different forms. Kazakhs fleeing the Uyghur region into Kazakhstan are often arrested for trespassing Kazakhstan’s border before being sent to court, where in their testimonies, they describe their experiences in the Uyghur region.18There are two Kazakhstan-based organizations conducting this type of work: Ata-jurt Eriktileri, and the Xinjiang Victims Database (XVD). Both seek to document and promote the narratives of individuals escaping from Xinjiang. The XVD in particular has become a reference point for many international tribunals and related documents, as well as Michele Bachelet’s report on Xinjiang for the UN Office of the High Commission for Human Rights. For more, see: Mehmet Volkan Kaşıkçı, “Documenting the Tragedy in Xinjiang: An Insider’s View of Atajurt,” The Diplomat, January 16, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/01/documenting-the-tragedy-in-xinjiang-an-insiders-view-of-atajurt/; Xinjiang Victims Database, https://shahit.biz/eng/; “OHCHR Assessment of human rights concerns in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China,” United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, August 31, 2022, https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/countries/2022-08-31/22-08-31-final-assesment.pdf Kazakhstan’s courts grant temporary asylum status to these refugees, generally lasting about a year, after which point individuals have had to leave Kazakhstan. Temporary asylees have included former detainee, activist and author Dr. Sayragul Sauytbay, as well as Tursunay Ziawudun, who has testified all over the world about her experiences in the camps. However, very little support or mutual aid is offered to these refugees from outside of the community or beyond other individual members of the broader diaspora – the government does little to help resettle these Kazakhs.

The government of Kazakhstan’s official stance on Kazakhs fleeing the Uyghur region is twofold: the government firmly denies the existence of the camps in the region. Still, it has successfully negotiated the release of Kazakhs from the Uyghur region on at least two occasions. In a December 2019 interview with Deutsche Welle, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev stated that Kazakhstan would not interfere in China’s affairs and that Kazakhstan would not become a front in a global anti-China movement.19“Президент Казахстана: У нас нет культа личности,” Deutsche Welle, December 4, 2019, https://bit.ly/3BYdEfe The Chinese government thanked Kazakhstan for its “support and understanding” of its “position” in the Uyghur region in March 2019, adding that others should follow its example. However, in January 2019, the government of Kazakhstan announced it had successfully negotiated the release of 2,000 Kazakhs from the Uyghur region. These Kazakhs, many of whom have dual citizenship and/or families in Kazakhstan, would be allowed to apply for permanent residency or citizenship, according to Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.20It is unclear if this provision is under the auspices of the Kandas (fka Oralman) policy. Under that policy, a person has to apply for this status which requires identification documents, and a notarized translation of those documents; Kazakhs can only apply in Shymkent, Astana, or Almaty, then once the application is submitted, Kazakhs receive a reply within four days; people who receive Kandas status get a certificate stating so which acts as their official documentation until they become citizens of Kazakhstan, at which point they are no longer Kandas. Further, it is unclear how Kazakh escapees from Xinjiang interact with this policy. For more, see: “Issuance of Permit for Accommodation by Foreign Citizens and Stateless Persons for Permanent Residence in the Republic of Kazakhstan,” Kazakhstan E-Government, accessed September 24, 2022, https://egov.kz/cms/en/services/009pass_mvd; “Kandas in Kazakhstan: Help, Privileges, Adaptation,” Kazakhstan E-Government, accessed September 24, 2022, https://egov.kz/cms/en/articles/kandas_rk; “Status and Rights of Kandas,” Kazakhstan E-Government, accessed September 24, 2022, egov.kz/cms/en/articles/kandas_rights_conditions This came after the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had negotiated for the release of 15 Kazakhs in November 2018.21“China Allowing 2,000 Ethnic Kazakhs to Leave Xinjiang Region,” AP News, April 20, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/kazakhstan-ap-top-news-international-news-asia-china-6c0a9dcdd7 bd4a0b85a0bc96ef3dd6f2

Kazakhs who have escaped, as well as those with family members still in the Uyghur region, have become some of the most powerful advocates for Kazakhs and Uyghurs in the camps, offering first-hand testimonials about their family members, friends, former neighbors, and colleagues still in the Uyghur region. In particular, Ata-Jurt Eriktileri and its successor organization Ata-Jurt Eriktileri Naghuz have collected written and video testimonials of Kazakhs and Uyghurs, providing critical documentation of the Chinese state’s human rights violations. According to Gene Bunin, the Xinjiang Victims Database – the most comprehensive set of data on the victims of the Chinese government’s atrocities – would not exist without Ata-Jurt Eriktileri.22Mehmet Volkan Kaşıkçı, “Documenting the Tragedy in Xinjiang: An Insider’s View of Atajurt,” The Diplomat, January 16, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/01/documenting-the-tragedy-in-xinjiang-an-insiders-view-of-atajurt/ Current organization members have also sought to bring attention to the plight of Uyghurs and Kazakhs in the camps more directly. Baibolat Kunbolatuly has protested outside the Chinese consulate in Almaty, Kazakhstan, almost every single day since early 2020. Having been arrested multiple times by Kazakhstan’s police and security services for violating Kazakhstan’s restrictive laws against protesting, he has persisted in his campaign, demanding further information about his brother. Kunbolatuly is frequently joined by others seeking information about family members in the Uyghur region.23“‘Your Heart Might Stop’: Kazakh From Xinjiang Threatened After Pressing Chinese Diplomats About Missing Brother,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, March 18, 2021, https://www.rferl.org/a/china-xinjiang-kazakhstan-missing-threats-protests/31157124.html; “Kazakh Man Gets 10 Days In Jail For Picketing Chinese Consulate In Almaty,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, February 10, 2021, https://www.rferl.org/a/kazakh-man-gets-10-days-in-jail-for-picketing-chinese-consulate-in-almaty/31095510.html; “Kazakhstan: Activist Detained for Hypothetical Anti-China Picket,” Eurasianet, July 1, 2021, https://eurasianet.org/kazakhstan-activist-detained-for-hypothetical-anti-china-picket; Berikbol Dukeyev, “Do Kazakhstanis Care about Their Kin in Xinjiang?,” openDemocracy, June 7, 2021, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en /odr/do-kazakhstanis-care-about-their-kin-xinjiang/; Miriam Kiparoidze, “Kazakhstan Is Arresting Protesters Seeking Information about Missing Relatives in Xinjiang,” Coda Story, August 6, 2021, https://www.codastory.com/disinformation/kazakhstan-xinjiang/ Ahead of Xi Jinping’s September 2022 visit to Kazakhstan, Kazakhs who protested the incarceration of their families in Xinjiang were detained. Gulfia Qazybek, Khalida Aqytkhan, and Gauhar Qurmanalieva were taken off a bus traveling between Almaty and Shymkent and told that if they protested in Astana during Xi’s visit they would face up to 15 days in jail, and that the Chinese government would put pressure on their relatives in Xinjiang.24“Ahead of Xi’s Visit, Pressure Increases on Kazakhs Who Have Protested Relatives’ Detention in Xinjiang,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, September 12, 2022, https://www.rferl.org/a/kazakh stan-china-xi-visit-xinjiang-relatives-pressure/32030416.html

Kazakhstan is home to the largest Uyghur community outside the Uyghur region with over 300,000 Uyghurs living in the Central Asian state, primarily in Almaty oblast between Zharkent and the city of Almaty.25Sean Roberts and Dana Rice, “Kazakhstan’s Ambiguous Position towards the Uyghur Cultural Genocide in China,” The Asan Forum (blog), October 23, 2020, https://theasanforum.org/kazakh stans-ambiguous-position-towards-the-uyghur-cultural-genocide-in-china/; Rachel Harris and Zulfiyam Karimova, “Women’s Chay Gatherings in Kazakhstan: Sustaining Identity in Migrant Communities,” in Community Still Matters: Uyghur Culture and Society in Central Asian Context, eds Rachel Harris and Zulfiyam Karimova (Hawaii, NIAS Press, 2022), 201–217. Uyghurs are represented in the Assembly of Peoples of Kazakhstan, a government body that acts as a forum for Kazakhstan’s ethnic minorities, by Rustam Kairiyev. Kairiyev, who was born in Almaty, is also the leader of the Uyghur Youth of Kazakhstan organization, and an active member of the Uyghur Ethnocultural Center of Kazakhstan.26“Выступление Председателя РОО «Союз уйгурской молодежи Казахстана» Р.Кайрыева,” Ассамблея народа Казахстана, accessed August 22, 2022, https://assembly.kz/ru/sess/vystu plenie-predsedatelya-roo-soyuz-uygurskoy-molodezhi-r-kayryevakazakhstana/ Outside of these avenues, which are largely controlled by the state, however, Uyghur activities have been suppressed by the government of Kazakhstan since the early 2000s.27Sean Roberts and Dana Rice, “Kazakhstan’s Ambiguous Position towards the Uyghur Cultural Genocide in China,” The Asan Forum (blog), October 23, 2020, https://theasanforum.org/kazakh stans-ambiguous-position-towards-the-uyghur-cultural-genocide-in-china/ Further, since the late 1990s, researchers have observed that as the government of Kazakhstan has articulated and re-articulated Kazakhstan’s national identity, the Uyghur language, culture, and identity are being marginalized as the government of Kazakhstan privileges Kazakh culture.28Regina Uyghur and Yadikar Ganiyev, “Caught Between Two Fires: The Plight of The Uyghur Community in Kazakhstan,” in Community Still Matters: Uyghur Culture and Society in Central Asian Context, eds Rachel Harris and Zulfiyam Karimova (Hawaii, NIAS Press, 2022). Local tensions have also been known to flare below the state level. In November 2021, a brawl broke out, first between Kazakh and Uyghur students at a local school, before spreading into the wider community. Residents of the village Penzhim, with a population of just over 5,300, described underlying tensions in the community that had been building before the brawl.29Manas Qaiyrtaiuly and Farangis Najibullah, “Life Returns To ‘Normal,’ But Divisions Remain In Kazakh Village After Ethnic Clashes,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, November 12, 2021, https://www.rferl.org/a/kazakhs-uyghurs-village-ethnic-tensions/31556879.html

While Kazakhstan has sought to free Kazakhs living in the Uyghur region, the government has done little to support the needs of displaced Kazakhs and Uyghurs living in its territory. It has even gone so far as to threaten, harass, and endanger those who advocate for further awareness of China’s human rights atrocity crimes in the camps. Further, since January 2022, when the government of Kazakhstan cracked down on protesters demanding better working and living conditions, Kazakhstan’s authoritarian government has grown even less tolerant of CSOs, with activists arrested, proposals for legislation threatening to further curtail individuals’ and organizations’ freedom of speech and assembly, and a refusal to register opposition organizations.30“Kazakhstan: Civic Space Limited by Continued Fallout from January 2022 Events,” International Partnership for Human Rights (blog), May 2, 2022, https://www.iphronline.org/ kazakhstan-civic-space-limited-by-continued-fallout-from-january-2022-events.html

However, despite that reality, there have been grassroots efforts to meet the humanitarian needs of Kazakh escapees from the Uyghur region, particularly those requiring medical attention. The International Legal Initiative (ILI) and local researchers have successfully crowdsourced hearing aids for a Kazakh man who lost most of his hearing during beatings by Chinese guards while detained in the Uyghur region.31“Medical Examinations for Xinjiang Ex-Detainees,” organized by Gene Bunin, gofundme.com, accessed August 30, 2022, https:/www.gofundme.com/f/medical-examinations-for-xinjiang-exdetainees ILI has also advocated for the return of Kazakhs from the Uyghur region, with a positive response from the government of Kazakhstan in 100 of the 162 cases ILI has worked on. However, the leader of ILI noted that many of these Kazakh returnees struggled to gain citizenship or find work, and continued to suffer from psychological trauma, often the result of torture.32Chris Rickleton, “Kazakhstan: After Xinjiang, the Long Road to Recovery,” Eurasianet, September 11, 2019, https://eurasianet.org/kazakhstan-after-xinjiang-the-long-road-to-recovery

Kyrgyzstan

China is one of Kyrgyzstan’s primary economic partners, with China accounting for almost half of Kyrgyzstan’s FDI inflows.33“China and Kyrgyzstan: Bilateral Trade and Future Outlook,” China Briefing News, August 27, 2021, https://www.china-briefing.com/news/china-and-kyrgyzstan-bilateral-trade-and-future-outlook/ Kyrgyzstan is also in debt to the Chinese government for up to USD 5 billion, or about 40 percent of the Kyrgyz government’s foreign debt.34Reid Standish, “How Will Kyrgyzstan Repay Its Huge Debts To China?” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, February 27, 2021, https://www.rferl.org/a/how-will-kyrgyzstan-repay-its-huge-debts-to-china-/31124848.html; “China and Kyrgyzstan: Bilateral Trade and Future Outlook,” China Briefing News, August 27, 2021, https://www.china-briefing.com/news/china-and-kyrgyzstan-bilateral-trade-and-future-outlook/ Ethnic Kyrgyz people are disappearing into the Chinese government’s camps in the Uyghur region.35“Xinjiang Authorities Holding Hundreds From Kyrgyz Village in ‘Political’ Re-Education Camps,” Radio Free Asia, December 4, 2018, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/kyrgyz-12042018160255.html Between 2017 and 2018, during the winter break for universities in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, 54 Kyrgyz students returned to the Uyghur region and disappeared. As a result, 20 of them were expelled from their university programs. These students, many of whom were musicians, dancers, and poets, have not been seen or heard from since.36Gene Bunin, “Kyrgyz Students Vanish Into Xinjiang’s Maw,” Foreign Policy, March 31, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/03/31/963451-kyrgyz-xinjiang-students-camps/ The Kyrgyz government has not raised any objections with the Chinese government. Kyrgyzstan is home to about 50,000 Uyghurs.37Ryskeldi Satke, “Uighurs in Kyrgyzstan Hope for Peace despite Violence,” Al Jazeera, January 8, 2017, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2017/1/8/uighurs-in-kyrgyzstan-hope-for-peace-despite-violence

ILI has also advocated for the return of Kazakhs from the Uyghur region, with a positive response from the government of Kazakhstan in 100 of the 162 cases ILI has worked on.

In April 2022, a Christian Kyrgyz called Ovalbek Turdakun fled to the U.S. to give testimony on the mistreatment of Turkic minorities in the Uyghur region.38Chao Deng, “From a Chinese Internment Camp to the U.S., a Former Xinjiang Detainee Makes a Rare Escape,” The Wall Street Journal, April 12, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/former-xinjiang-detainees-arrival-in-u-s-marks-rare-escape-from-chinas-long-reach-11649775562 Before that, he had arrived in Kyrgyzstan in 2019, where he was repeatedly contacted by Chinese officials urging him to return to China; his bank account was frozen, and – after two years – Kyrgyz officials refused to renew his visa, putting him and his family at risk of deportation back to China.39Johana Bhuiyan, “Former Xinjiang Detainee Arrives in US to Testify over Repeated Torture He Says He Was Subjected To,” The Guardian, April 13, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/worl d/2022/apr/13/former-xinjiang-detainee-arrives-in-us-to-testify-over-china-abuses The government of Kyrgyzstan has yet to take an official stance on the Chinese human rights violations, despite written appeals from the families of detainees asking the Kyrgyz government to take action, and the demands of MPs to hear an explanation from the Kyrgyz Ministry of Foreign Affairs about what is “actually happening” in the Uyghur region.40“Kyrgyzstan: Officials Muted in First Words on Xinjiang Crackdown,” Eurasianet, November 27, 2018, https://eurasianet.org/kyrgyzstan-officials-muted-in-first-words-on-xinjiang-crackdow n

Separately, the government of Kyrgyzstan has blamed Uyghurs for many homicides and terror attacks on Kyrgyz soil. In 2000 and 2002, Chinese government representatives were attacked and killed in Kyrgyzstan. The Kyrgyz government attributed both attacks to Uyghurs. In 2016, the Chinese Embassy in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, was bombed; the Kyrgyz government attributed the attack to the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), an often mythologized Uyghur organization based in Afghanistan.41Ryskeldi Satke, “Uighurs in Kyrgyzstan Hope for Peace despite Violence,” Al Jazeera, January 8, 2017, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2017/1/8/uighurs-in-kyrgyzstan-hope-for-peace-despite-violence

In 2011, four Uyghur activists were escorted off a plane by Kyrgyz security officers without explanation. The activists were on route to a Uyghur conference in Canada.

Uyghurs in Kyrgyzstan have become increasingly distrustful of the Kyrgyz state; many Uyghurs report Kyrgyz intelligence and security services closely surveilling the community and harassing its members since before the collapse of the Soviet Union over concerns about Uyghur demands for greater autonomy.42Ryskeldi Satke, “Uighurs in Kyrgyzstan Hope for Peace despite Violence,” Al Jazeera, January 8, 2017, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2017/1/8/uighurs-in-kyrgyzstan-hope-for-peace-despite-violence In recent years, the government has sought to prevent Uyghur organizations from convening and prevented Uyghurs living in Kyrgyzstan from attending larger international Uyghur meetings. In 2011, four Uyghur activists were escorted off a plane by Kyrgyz security officers without explanation. The activists were on route to a Uyghur conference in Canada.43Cristina Maza, “Kyrgyzstan’s Uighurs Cautious, Still Fear Chinese Influence,” November 25, 2014, Eurasianet, 2022, https://eurasianet.org/kyrgyzstans-uighurs-cautious-still-fear-chinese-influence Since Sadyr Japarov became president of Kyrgyzstan, the space for civil society in Kyrgyzstan has shrunk considerably, with the government of Kyrgyzstan amending the constitution to more broadly constrain civil society.44Catherine Putz, “Concerns Swirl Around Kyrgyzstan’s Draft Constitution: Presidential Power, Judicial Independence, and Civil Society,” The Diplomat, March 22, 2021, https://thediplomat.com /2021/03/concerns-swirl-around-kyrgyzstans-draft-constitution-presidential-power-judicial-independence-and-civil-society/; “Kyrgyzstan: Controversial NGO Law Passes,” Institute for War and Peace Reporting, July 19, 2021, https://iwpr.net/global-voices/kyrgyzstan-controversial-ngo-law-passes

Turkey

Historically, Turkey has been the primary location of the Uyghur diaspora community outside of Central Asia. As many as 50,000–60,000 Uyghurs live in the country today, according to estimates, but the community remains vulnerable to Beijing’s reach. The Turkish government has been an on-again, off-again supporter of Uyghur rights and has from time-to-time voiced concern about the Chinese government’s repression of Uyghurs. The Uyghur issue is often instrumentalized in Turkish politics to gain concessions from China, to show leadership in the Muslim world, or to play up to certain political and ideological factions in domestic politics. In 2009, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan called the Chinese government’s crackdown in the aftermath of the unrest in Ürümchi “an act of genocide.”45“Turkish Leader Calls Xinjiang Killings ‘Genocide,” Reuters, July 10, 2009, https://www.reu ters.com/article/us-turkey-china-sb/turkish-leader-calls-xinjiang-killings-genocide-idUSTRE5 6957D20090710 Since 2016, Erdogan’s tone has shifted markedly. While the Turkish leader reiterated in 2015 that his country’s doors would remain open to Uyghur refugees, he has become less vocal in championing their cause, instead moving closer to Beijing after several high-profile Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) meetings with members of the Chinese business community, and Turkish Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu has warned Uyghur protesters to stop spreading “American propaganda.” In 2017, Erdoğan signed a controversial extradition treaty with China, which the Chinese government approved in December 2020. However, citizen voices mobilized opposition parties to raise concerns, leaving the treaty unratified by the Turkish parliament. As the Turkish government moves closer to China in the name of international economic partnerships and bilateral alliances, Turkey has become more dangerous for Uyghurs.46Bradley Jardine, “Great Wall of Steel: China’s Global Campaign to Suppress the Uyghurs,” The Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars, March 2022, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/uploads/documents/Great%20Wall_of_Steel_rpt_web.pdf

In March 2020 U.S. broadcaster National Public Radio reported that as many as 400 Uyghurs were detained by Turkey’s security services in 2019 alone.47“‘I thought it would be safe’: Uighurs in Turkey now fear China’s long arm,” National Public Radio, March 13, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/03/13/800118582/i-thought-it-would-be-safe-uighurs-in-turkey-now-fear-china-s-long-arm In January 2021, several Uyghurs were detained by police in raids on their homes in Istanbul and threatened with deportation to China amid accusations of being affiliated with Islamic State.48“Uyghurs living in Turkey fear deportation to China as police detain dozens,” Stockholm Center for Freedom, January 22, 2021, https://stockholmcf.org/uyghurs-living-in-turkey-fear-deportation-to-china-as-police-detain-dozens/ Further, police banned Uyghur gatherings, citing concerns over the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. However, despite the ban many Uyghurs have attended protests outside the Chinese consulate in Istanbul in recent months, demanding information about their family, friends, neighbors, and other community members who had disappeared in the Uyghur region. In a separate incident, many Uyghurs were briefly detained by police after the Chinese embassy in Ankara complained about their protests.49Asim Kashgarian and Ezel Sahinkaya, “Turkey Cracks Down on Uighur Protestors after China Complains,” Voice of America, March 2021, https://www.voanews.com/a/east-asia-pacific_turkey-cracks-down-uighur-protesters-after-china-complains/6202920.html One Uyghur activist, Idris Hasan, fled the country after seeing his name on a list – made public by Turkish authorities – of Uyghur residents wanted by Beijing. He flew to Morocco but was detained in response to an Interpol notice (which was eventually removed, but Hasan still remains imprisoned).50Asim Kashgarian, “Uyghur Man’s Long Journey to Freedom May End with Return to China,” Voice of America, January 13, 2022, https://www.voanews.com/a/uyghur-man-s-long-journey-to-freedom-may-end-with-return-to-china/6395787.html

In March 2020 U.S. broadcaster National Public Radio reported that as many as 400 Uyghurs were detained by Turkey’s security services in 2019 alone.

Increasingly, the Chinese government is operating in Turkey largely unopposed. In February 2020, Jevlan Shirmemmet, a Uyghur living in Istanbul, had been campaigning for information about his mother’s whereabouts in the Uyghur region when he received a call from the Chinese Embassy in Ankara saying she had been arrested for allegedly “aiding terrorists.” Four months later, Jevlan Shirmemmet received another unexpected call from his father in the Uyghur region telling him to stop his activism. He received similar calls from his uncle and younger brother.51William Yang, “Uyghur man in Turkey demands answers from Beijing about his mom’s fate,” Deutsche Welle Mandarin service, July 27, 2020, https://williamyang-35700.medium.com/uyghur-man-in-turkey-demand-answers-from-beijing-about-his-moms-fate-f2a35c4a0221

In addition to its weakening rhetorical support for the Uyghur cause, Turkey has proven complicit in its arrests and harassment. In October 2016, Turkey imprisoned prominent Uyghur activist Abduqadir Yapchan, allegedly at the behest of the Chinese government. The 58-year-old Muslim religious teacher was born in Kashgar but had lived in Turkey since 2002. In 2003, China’s Party-state placed Yapchan on its first “terrorist list,” accusing him of having connections to ETIM. He was detained despite a Turkish court acquitting him of charges relating to terrorism.52Arslan Tash and Mamatjan Juma, “Turkish Court Rejects China’s Request to Extradite Uyghur Religious Teacher,” Radio Free Asia, April 2021, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/turkey -dismiss-04092021192932.html; “Exiled leader claims China is behind Turkey’s decision to detain a Uyghur activist,” Radio Free Asia via Refworld, October 10, 2016, https://www.refworld.org/ docid/5811ff12a.html Other Uyghurs say Turkey’s anti-terror forces have been visiting Uyghur neighborhoods and questioning community members about whether they have participated in anti-China movements.

As mass internment has intensified, Turkey has also clamped down on domestic media coverage of human rights atrocities in the Uyghur region. During an official visit to Beijing in August 2017, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu promised, “We’ll regard China’s security as our security. We’ll never allow any activities that threaten China’s sovereignty and security on our territory or the region we are in. We’ll eliminate any media reporting targeting China.”53Le Tian, “Turkish FM: China’s Security is Our Security,” China Global Times Network, August 2017, https://news.cgtn.com/news/3d557a4d7745544e/share_p.html

Turkey’s government has grown increasingly close to the Chinese government in recent years. In 2018, the countries signed a strategic partnership, signaling deeper coordination and cooperation. This partnership has been borne out in trade: in 2018, bilateral trade between China and Turkey amounted to USD 23.6 billion.54Asim Kashgarian, “Turkey Turns Down Citizenship for Some Uyghurs,” March 16, 2022, Voice of America, https://www.voanews.com/a/turkey-turns-down-citizenship-for-some-uyghurs/648 8401.html On at least one occasion, Uyghur investments in Turkey have attracted Beijing’s attention. Umer Hemdullah, an independent Uyghur bookstore owner in Sefakoy, tells us his two brothers in the Uyghur region had been planning to build a USD 100 million Uyghur traditional medicine facility in Ankara before China arrested them both for unknown reasons and the construction project was left abandoned.55Ahmet Hamdi Şişman, “China’s Uighur Persecution Leaves a Hospital in the Turkish Capital Stalled,” Straturka (blog), June 8, 2020, https://www.straturka.com/chinas-uighur-persecution-leaves-a-hospital-in-the-turkish-capital-stalled/ “We all had so much we planned to do for our people, but China has destroyed our lives,” he said. Umer Hemdullah was a religious scholar in Saudi Arabia until he fled to Istanbul in 2017 after the Chinese government refused to renew his passport. “I made it here with my wife and three of my children, but China refuses to allow two of my children to leave the [Uyghur region] and come to Turkey. The Turkish embassy in China says it has asked for their release but there have been no updates and the situation remains unchanged,” he said. In an orphanage we visited on the outskirts of Istanbul, several of the children told us that their parents – Turkish citizens – had been detained in the Uyghur region and that they were left alone in Turkey with only friends of their family to care for them.

Uyghurs in Turkey are expressing growing concern that they will no longer be safe in the face of these changing relations as they endure ongoing harassment, intimidation, and rendition through third-party countries.56Bradley Jardine, Edward Lemon, and Natalie Hall, “No Space Left to Run: China’s Transnational Repression of Uyghurs,” UHRP, June 24, 2021, https://uhrp.org/report/no-space-left-to-run-chinas-transnational-repression-of-uyghurs/ The Turkish government has, in other cases, sought to prevent the harassment and forcible rendition of other vulnerable communities within its borders: Turkish authorities have foiled two plots connected to the governments of Russia and Iran related to the attempted intimidation or abduction of individuals on Turkish soil.57“Turkey Foils Alleged Iran Plot to Kill Israelis in Istanbul,” Reuters, June 23, 2022, https://www .aljazeera.com/news/2022/6/23/turkey-foiled-iranian-plot-to-kill-israelis-in-istanbul-fm

VII. Legal and Technological Vulnerabilities

Transnational repression has become a hallmark of the Uyghur crisis. Beijing has used the family members of Uyghurs in the diaspora to intimidate them, compel their return, and pursue them through bilateral and multinational extradition efforts. This practice has further traumatized diaspora members, many of whom had been subjected to Beijing’s repressive policies before their displacement. Reaching diaspora members with humanitarian assistance – including protection, documentation, and psychosocial support – is frequently complicated by the nature of the community, mostly urban refugees with limited resources, and in many cases precarious legal status within their host country. This research will consider previous state practice in reaching vulnerable refugee and diaspora populations and the lessons that may be learned for the Uyghur community.

Statelessness and Refugee Challenges

Many Uyghurs and Kazakhs from the Uyghur region live in a state of legal precarity as undocumented or under-documented migrants in second countries. Statelessness, according to the U.S. Department of State, is defined by the breakdown between individuals’ de jure or de facto relationship to the state, meaning that individuals lack documentation connecting them to a particular state or that they are not recognized as citizens of a particular state.58“Statelessness,” United States Department of State (blog), accessed August 30, 2022, https://www.state.gov/other-policy-issues/statelessness/ This can be enforced through practices like those of the Chinese government, which, since the beginning of the crackdown, has routinely refused to renew the passports of Uyghurs living abroad, rendering them stateless, without valid identity papers of any kind, and therefore unable to travel.59“Weaponized Passports: The Crisis of Uyghur Statelessness,” UHRP, April 1, 2020, https://uhrp.org/statement/weaponized-passports-the-crisis-of-uyghur-statelessness/ This statelessness further exposes the Uyghur community to the threat of arrest and potential deportation. The right to nationality is recognized in a series of international human rights instruments, including Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). As a UN member, China is obliged to meet the provisions of the UDHR; however, in the international system the UDHR is viewed as lex ferenda, or the law as it should be, making enforcement near impossible.60International standards relating to nationality and statelessness,” United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, accessed on September 19, 2022, https://www.oh chr.org/en/nationality-and-statelessness/international-standards-relating-nationality-and-statelessness

Further, in 2022, the government of Turkey started to deny some Uyghurs’ citizenship applications based on “risks to national security,” or “social order.” Uyghurs have been shocked and even traumatized by these communications. They are at a loss to understand why they would be considered by the Turkish state to be a “risk to national security” or a “risk to social order,” especially those who deliberately stayed away from peaceful protests or any online advocacy or publicity about the fate of their families back home. The existence of such denials has caused extreme alarm, affecting even those who did not receive a denial on these grounds, (for example, those who already have temporary or permanent residence status).

“I made it here with my wife and three of my children, but China refuses to allow two of my children to leave the [Uyghur region] and come to Turkey. The Turkish embassy in China says it has asked for their release but there have been no updates and the situation remains unchanged,” he said.

The denials on these grounds heightened Uyghurs’ fears that at any time the Turkish government could take action against them, whether to cut off employment or educational options, to detain them or to deport them. Some of the Uyghurs who have had their applications denied have since left Turkey, instead relocating to a secondary host country in Europe. Previously, the Turkish government allowed Uyghurs to become citizens, and indicated that it would continue to do so, accepting 8,000 applications for citizenship in 2021 alone.61Asim Kashgarian, “Turkey Turns Down Citizenship for Some Uyghurs,” Voice of America, March 16, 2022, https://www.voanews.com/a/turkey-turns-down-citizenship-for-some-uyghurs/6488401.html. No updated information about the status of these applications has been made available. However, one interviewee we spoke to, Leo, pointed out Uyghurs’ fear that if they apply for a Turkish passport, it makes any future asylum claims in European countries more challenging, as they cannot claim to be at immediate risk of deportation to China. Leo observed, “I spoke with one woman who can’t meet her family in Europe, and she has been weighing up whether to apply for Turkish citizenship or whether this would just make reconnecting with her family more difficult. The problem is worse due to the expiration of passports as many European states don’t accept refugees without passports or government-issued identity papers.”

This dilemma has created intense fear and uncertainty, as Uyghurs in the diaspora community fear that there is no pathway to resolve the legal limbo, raising the prospect of being unable to obtain legal status in any country, and leaving them permanently unable to obtain safe haven from the risk of deportation, and unable to earn an income or provide for their children’s education and material needs. In Kazakhstan, many Uyghur and ethnic Kazakh refugees fleeing China to Kazakhstan are not permitted to stay for longer than a year, meaning that they have to migrate onward for their safety and security. Ersin Erkinuly, a Kazakh, escaped the Uyghur region to Kazakhstan in late 2019. However, he did not feel safe from deportation there; in 2020, he fled first to Turkey and then to Ukraine. After trying to flee to other European countries, Erkinuly was detained several times by the Ukrainian authorities. He was released in Kyiv when Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. Erkinuly escaped to Poland and then to Germany, where he was detained in July 2022.62Asim Kashgarian, “From China to Turkey, Ukraine: 2 Men’s Search for Safety,” Voice of America, March 5, 2022, https://www.voanews.com/a/from-china-to-turkey-ukraine-2-men-s-search-for-safety/6471359.html; Catherine Putz, “Ethnic Kazakh From Xinjiang Detained in Europe, Again,” The Diplomat, July 15, 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/07/ethnic-kazakh-from-xinjiang-detained-in-europe-again/

Constant migration requires funds, documentation, and a safe endpoint — which, as our research indicates, are far from guaranteed. Ethnic-Kyrgyz refugees to Kyrgyzstan are also not given asylum status and are instead given a “special resident permit,” which can be renewed for up to five years.63“Legal Status of Foreign Nationals in the Kyrgyz Republic,” HG Legal Resources, accessed August 30, 2022, https://www.hg.org/legal-articles/legal-status-of-foreign-nationals-in-the-kyrgyz-republic-4891 However, as in Ovalbek Turdakun’s case, the Kyrgyz government refused to renew his permit after two years, which suggests that this matter is highly discretionary and inconsistent.64Johana Bhuiyan, “Former Xinjiang Detainee Arrives in US to Testify over Repeated Torture He Says He Was Subjected To,” The Guardian, April 13, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com /world/2022/apr/13/former-xinjiang-detainee-arrives-in-us-to-testify-over-china-abuses

Nevertheless, there is a solution to this statelessness. In Sweden, Germany, and Canada, immigration agencies can access accurate and up-to-date information on the political situation in countries of origin and the threats to political, religious, and ethnic minorities when assessing asylum applications through systems they have built. The availability of this information increases awareness among immigration officials about different forms of repression used by origin states. It also helps to build resistance to extradition or repatriation requests by authoritarian governments. These systems could be further strengthened by thorough vetting procedures for any interpreters employed at the agencies to ensure that they are not acting as agents of, or vulnerable to the demands of, a foreign state. Immigration agency staff should also be trained on authoritarian states’ motives and tactics for engaging in transnational repression. Staff also need to be mindful of the difference between Han and Uyghur asylum seekers, the different threats they face, and the linguistic needs they have.

In the U.S., a large and complicated immigration system has resulted in a back-logged system: as of the end of 2020, there were more than 386,000 overall pending applications for affirmative asylum in the U.S. from around the world.65Affirmative asylum claims are made by people who are not in removal proceedings and are proactively seeking protection from persecution within the United States. This lack of security deters Uyghurs’ ability and desire to engage in activism, discourages contact with law enforcement, and seriously impacts their day-to-day health and livelihoods. As one Uyghur, Ahmad, noted to us, “My asylum application has been pending since May 2019, and I have no clarity. It makes me feel nervous and afraid, and it is hard to build a life living in that state of mind. They just keep telling me they have a backlog of applications. For several months 20–30 of us would gather at the office in Fairfax [Virginia] to protest the delays and make officers aware of our situation and struggles. There are a significant number of us still awaiting these asylum interviews.”66Bradley Jardine, interview with Ahmad, audio, September 19, 2022.

Uyghurs have also expressed that the persistent lack of status in the U.S. poses an additional challenge: the filing fees — many of which are higher for individuals without prior status in the U.S. — and “endless” requirements for paperwork, as well as the need for documentation such as birth certificates, which are all but impossible for Uyghurs to obtain from the Chinese government.67Bradley Jardine, interview with Dr. Henryk Szadziewski. Initial reports indicate that USCIS now recognizes and accommodates cases where official documents are unobtainable; UHRP and other NGOs are currently seeking clarification. Some Uyghurs we have interviewed have noted that they have received aid for fees from other members of the Uyghur community, but as far as we are aware there is no dedicated effort in place to provide such assistance.

“My asylum application has been pending since May 2019, and I have no clarity. It makes me feel nervous and afraid, and it is hard to build a life living in that state of mind.”

International organizations have heightened this sense of precarity. Interpol – formally the International Criminal Police Organization – facilitates international cooperation on criminal matters.68Interpol notices are a method for distributing information about wanted or missing people and stolen passports among member states; they are not international arrest warrants. Interpol prohibits its members from using notices to engage in political, military, or religious activities. This means that countries should only submit notices and diffusions in cases of ordinary, non-political crime. A diffusion is information that is shared directly between member states rather than by Interpol. Despite this, in a practice that has come to be known as “Interpol abuse,” the governments of countries, including China, issue Interpol Red Notices in an attempt to induce other governments to detain exiles and dissidents beyond their borders as in the case of Idris Hasan detained in Morocco.

As a result of these challenges to legal immigration and Uyghurs’ risk of enforced statelessness, many Uyghurs cannot work legally or send their children to school. This precarity presents a humanitarian need that has gone largely unmet. One Uyghur living in Turkey told us in September 2022 that he could not get a driver’s license and that he and his family were dependent on his wife, who made bedding at home and sold it on the street, and that their children were unable to attend school. He added that about 300 Uyghurs in Istanbul were illicitly renting stalls on a day-to-day basis in the bazaar to sell goods.69“Weaponized Passports: The Crisis of Uyghur Statelessness,” UHRP, April 1, 2020, https://uhrp.org/statement/weaponized-passports-the-crisis-of-uyghur-statelessness/

Cyberattacks

Since 2002, the Chinese state has engaged in an unparalleled campaign of digital transnational repression as part of its efforts to coerce and control Uyghurs living abroad. The Chinese government and its security services have leveraged the interconnectivity of the globalized, digital world and are harassing Uyghurs living abroad. This approach includes spyware, intelligence collection, data gathering, coercion-by-proxy, and intimidation. The Chinese Party-state has used these tools to silence Uyghurs living abroad, in some cases to great effect; in others, the Chinese government’s attempts to stifle Uyghur voices have only made Uyghurs speak louder and push for their voices to be heard.

Most of the cases we documented in our November 2021 report, “Your Family Will Suffer,” were incidents of cyberattacks and malware — often in a bid to collect information on Uyghurs and their activities abroad. Relatedly, the next most common trend was intelligence and data collection, often coupled with coercion-by-proxy, with the Chinese government threatening Uyghurs’ families in the Uyghur region unless the diaspora Uyghurs handed over data about themselves, their friends and neighbors, or their community in their country of exile. We also found many documented cases of coercion-by-proxy on foreign soil, in which Uyghurs were told to return to the Uyghur region to prevent their families from being arrested and put in the camps. These methods offer a window into the persistent harassment, intimidation, and everyday insecurity Uyghurs experience at the hands of the Chinese state.

In our report, we surveyed 72 Uyghurs living in diaspora communities in liberal democracies across North America, the Asia Pacific, and Europe, 95.8 percent of whom reported feeling threatened, and 73.5 percent of whom noted that they had experienced digital risks, threats, or other forms of online harassment.

Technology companies have sought to address the many ways that their tools can be used for malign purposes through creating special safety programs for individuals who are at high risk. Google has rolled out an Advanced Protection Program, and Facebook has Facebook Protect, which is meant to support targeted individuals. Facebook, in particular, has become a critical place for Uyghurs to meet and be part of a larger community. While tech companies have set up these programs, many in at-risk communities remain unaware of how to use them. They may also feel that even if the programs work as intended, Chinese agents have so many other ways to reach them to intimidate or coerce them, that it is useless to try using these tools.

In “Your Family Will Suffer,” we surveyed 72 Uyghurs living in diaspora communities in liberal democracies across North America, the Asia Pacific, and Europe, 95.8 percent of whom reported feeling threatened, and 73.5 percent of whom noted that they had experienced digital risks, threats, or other forms of online harassment.70Natalie Hall and Bradley Jardine, “‘Your Family Will Suffer’: How China Is Hacking, Surveilling, and Intimidating Uyghurs in Liberal Democracies,” UHRP, November 10, 2021, https://uhrp.org/report/your-family-will-suffer-how-china-is-hacking-surveilling-and-intimidating-uyghurs-in-liberal-democracies/ Members of Uyghur communities worldwide are interested in protecting themselves, with 89.7 percent of respondents expressing interest in increasing their security knowledge. However, many respondents did not feel that this protection would necessarily come from their home governments – 44.1 percent felt that their host governments take the intimidation they face seriously, while only 20.5 percent felt that the host governments would fix these issues.71Natalie Hall and Bradley Jardine, “‘Your Family Will Suffer’: How China Is Hacking, Surveilling, and Intimidating Uyghurs in Liberal Democracies,” UHRP, November 10, 2021, https://uhrp.org/report/your-family-will-suffer-how-china-is-hacking-surveilling-and-intimidating-uyghurs-in-liberal-democracies/ To answer this rising tide of digital repression, governments and technology companies must work closely with civil society and targeted individuals and communities.

VIII. Psychosocial Vulnerabilities of Uyghurs Living in Diaspora Communities

Uyghurs abroad face complex challenges as survivors or secondary survivors of an ongoing genocide. These psychosocial challenges present a threat to Uyghurs’ short-term and long-term well-being. Every member of the diaspora community has been cut off from family and their homeland for the past six years, and this situation is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future. Until the Chinese government’s Xinjiang policies change, the Uyghurs will essentially be an exile community, given the progressing stamping out of the Uyghur identity and community in their homeland. The psychosocial impacts of community-wide trauma stemming from the genocide and the prospect of multi-generational exile include damage to emotional wellbeing and relationships; family, kinship and community networks; social values; and cultural survival.72Adapted from “What Is Psychosocial Support?” Papyrus, October 2, 2018, https://papyrus-project.org/what-is-psychosocial-support/

As more Uyghurs have disappeared into the camps, more of their loved ones living abroad have been stranded without their primary providers and caretakers, resulting in a growing number of orphaned and homeless Uyghurs.

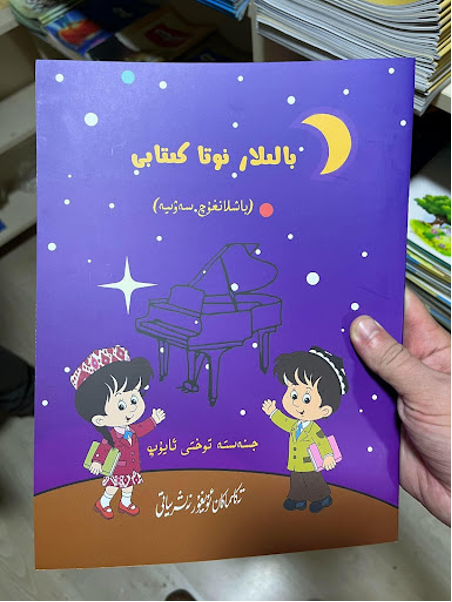

This section examines diaspora Uyghurs’ economic, social, and psychological deprivations requiring a humanitarian response. As a result of the Chinese government’s human rights violations in the Uyghur region, Uyghurs and other Turkic survivors have been stripped of their properties and cut off from their assets.73See: “Under the Gavel: Evidence of Uyghur-owned Property Seized and Sold Online,” UHRP, September 21, 2021, https://uhrp.org/report/under-the-gavel-evidence-of-uyghur-owned-property-seized-and-sold-online/ Targeted persecution abroad also includes withholding passports, birth certificates, and other identity papers required for economic self-sufficiency and livelihoods, whether operating a business, obtaining a legal permit to work, enrolling children in school, or obtaining higher education and skills certifications for employment. As a result, Uyghurs abroad live in a persistent precarity that impacts their economic well-being and that of their families, as well as their psychological well-being. Individual trauma also affects overall health and ability to attend to studies, work, and family responsibilities. Lastly, this section examines the impact of cultural and linguistic erasure in the Uyghur region. Diaspora communities and CSOs have sought to protect Uyghur culture and identity, as well as to continue teaching Uyghurs.

Family Separation, Single-Parent Families, Orphans, Homelessness

The Chinese government’s human rights violations in the Uyghur region have separated families worldwide. Interviewees estimated that in Turkey alone, there are at least 1,000 children without parents.74Bradley Jardine, interview with Hikmet Hasanoff, September 7, 2022. Some were previously sent abroad to study, some were staying with overseas relatives when their parents were suddenly detained during a family visit or business trip back to China (undertaken before the extent of the crackdown was known). These unaccompanied minors often lack documentation, means to protect themselves, or a way to earn money, making them highly vulnerable to trafficking. When stateless, Uyghurs cannot find legal jobs in their adopted host countries, forcing them to engage in the shadow economy to survive. Children cannot attend school without proper documentation. As more Uyghurs have disappeared into the camps, more of their loved ones living abroad have been stranded without their primary providers and caretakers, resulting in a growing number of orphaned and homeless Uyghurs. In Turkey, Uyghur children have joined criminal gangs, with some as young as 14 and 15 being drawn toward crime and drugs.

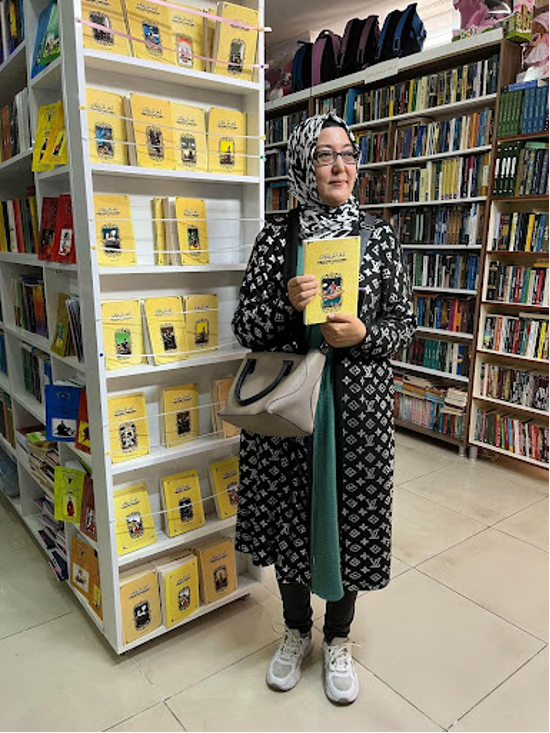

Hikmet Hassanoff, founder of the Shukr Foundation, estimates that there are about 2,000–3,000 “widows” and 1,000 orphans living in Turkey. These “widows” – women whose husbands have been imprisoned or detained – often lack the Turkish language skills or adequate documentation to access necessary medical care and schooling for themselves and their families. Hikmet Hasanoff observed that many women lack employable skills, as they have not traditionally been responsible for the financial well-being of their families. This has only been compounded by the realities of the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting inflation: “Many [women] who had found work in restaurants or washing dishes were forced out of work after COVID-19, and they have struggled to get back on their feet… The heavy inflation in Turkey has destroyed these income streams, and where people had previously been surviving, they are now barely making ends meet.” Another interviewee, Leo, noted that in Turkey, Uyghur small businesses have been negatively impacted by the depreciating currency and inflation, and many people were either forced to quit their jobs or sell their businesses to work in factories.75Bradley Jardine, interview with Leo, audio, September 21, 2022.

As more Uyghurs have disappeared into the camps, more of their loved ones living abroad have been stranded without their primary providers and caretakers, resulting in a growing number of orphaned and homeless Uyghurs.

This family separation is closely related to collective trauma, with many Uyghurs reporting sadness, trauma, and loss related to being separated from their families. “In 2017, I lost all contact with my family after the mass arrests began. Soon after, I deleted WeChat and apps I had used to communicate with them as I was afraid I would put them in danger,” Ahmad, a Uyghur living in Virginia, told us. “I became deeply depressed and struggled.” Gauhar Qurmanalieva, a woman based in Kazakhstan, confirmed to us that she had not spoken to her family members in the Uyghur region since 2018 because they were afraid of the consequences. Another Uyghur living in Istanbul who used the name Nufisa told the Shukr Foundation, “The pain of not knowing what has become of our parents and relatives is unbearable… Because we don’t have our own land, we rely on each other perhaps more than other people… All we have is each other. The thought that we might never see or hear from them again is a torment I can’t describe. I feel as if I have been torn into a million pieces… The simple thought of what has happened and is happening now is a sharp pain that never goes away.”76Ruth Ingram, “Time Is No Healer for Uyghur ‘Widows’ and ‘Orphans’ in Turkey,” Bitter Winter Magazine, June 6, 2019, https://bitterwinter.org/time-is-no-healer-for-uyghur-widows-and-orphans-in-turkey/

Collective Trauma

Uyghurs worldwide are experiencing ongoing grief, survivor’s guilt, and other forms of intense emotional distress due to the Chinese government’s human rights violations in the Uyghur region. In short, the Uyghur diaspora is suffering collective trauma. A variety of other terms refer to the same experience, including community-wide trauma, historic grief, historical trauma, intergenerational posttraumatic stress disorder, intergenerational trauma, and multigenerational trauma.77Wehmah Jones and Tammie M. Causey-Konaté, “Understanding Collective Trauma,” National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), Institute of Education Sciences (IES), U.S. Department of Education, accessed on January 17, 2023, https://ies.ed.gov /ncee/edlabs/regions/southwest/events/pdf/2021jan21/Addressing-Collective-Trauma-2-508.pdf

Uyghurs have been separated from their families, friends, and loved ones; many report harassment while living abroad. As has been reported in The New York Times and other media,78See, for example: Amy Qin and Sui-Lee Wee, “‘A Daily Cloud of Suffering’: A Crackdown in China Is Felt Abroad,” New York Times, June 11, 2021, https://tinyurl.com/2s4eja5m, and Andrew McCormick, “Uyghurs outside China are traumatized. Now they’re starting to talk about it,” MIT Technology Review, June 16, 2021, https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/06/16/ 1026357/uyghurs-china-minorities-trauma-telehealth-social-media/ Uyghur communities are experiencing ongoing trauma and the full range of effects often grouped under the rubric of complex post-traumatic stress (CPTSD), which has also been found among other communities of displaced and persecuted refugees.79Angela Nickerson et al., “The Factor Structure of Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Traumatized Refugees,” European Journal of Psychotraumatology 7, no. 1 (December 2016): 33253, https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v7.33253 They experience ambiguous loss, ongoing unresolved grief, and survivor’s guilt, with effects including depression, anxiety, sleep disorders including night terrors, insomnia, and intra-familial stress. According to an informal online survey conducted by Dr. Memet Imin in 2018, 90 percent of the almost 1,100 Uyghur respondents were experiencing “deep psychological stress.” According to Dr. Imin’s research, Uyghurs across the diaspora community often experience “feelings of hopelessness, anger, and depression.” Almost 25 percent of respondents said they regularly experienced thoughts of suicide – roughly five times the adult average in the U.S.80“Suicide,” National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), accessed August 22, 2022, https://w ww.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide Dr. Imin noted that this was likely an undercount due to fears of sharing information in the context of active espionage attempts in Uyghur communities and the stigmatization of discussing these challenges.81According to London-based The Rights Practice, Uyghurs living in the UK “live in fear of the Chinese state.” According to their reporting, 62 percent of those surveyed were “worried about being followed and monitored by Chinese authorities and alert to the presence of CCP spies in the UK who might use information about their activities overseas against family members back home.” For more, see Ruth Ingram, “Survivor’s Guilt, a Uighur Exile’s Constant Companion,” The New Arab, June 4, 2021, https://english.alaraby.co.uk/features/survivors-guilt-uighur-exiles-constant-companion, and “China’s long arm: How Uyghurs are being silenced in Europe,” Index on Censorship, February 2022, https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/ index-report-2022_uyghurs_web.pdf

Mehmet Tohti, founder and Executive Director of the Uyghur Rights Advocacy Project (URAP), described the trauma many Uyghurs in his community in Canada feel: “Our people have accumulated a great deal of trauma – it is like a toxic substance. You remember the pain every time you sit at a table alone and think of the loved ones who aren’t there. I haven’t seen my family for over 31 years. It’s a lifelong punishment from the Chinese state. Whoever you talk with, they all share remarkably common experiences wherever they reside. Not knowing the whereabouts or condition of loved ones is a constant torment.”82Bradley Jardine, interview with Mehmet Tohti, audio, September 6, 2022. Ahmad noted to us that the news of recent starvations as a part of the August–September 2022 “Zero Covid” policies in the Uyghur region had kept him up at night, made him very depressed, and affected his ability to focus and control his emotions, which has impacted relationships with friends and colleagues.

According to Dr. Imin’s research, Uyghurs across the diaspora community often experience “feelings of hopelessness, anger, and depression.” Almost 25 percent of respondents said they regularly experienced thoughts of suicide – roughly five times the adult average in the U.S.

These feelings, as Abdurresit Celil Karluk noted in his chapter in Exchange of Experiences for the Future: Japanese and Turkish Humanitarian Aid and Support Activities in Conflict Zones on Uyghur refugees in Turkey, are exacerbated by the feeling of “constantly being threatened.” Karluk notes: “This situation has caused the prevalence of serious psychological depression in migrants and revealed the situation of immigrants living in a sense of insecurity. [Uyghurs] could not benefit from any of the facilities provided to the Syrian [refugees]. [Uyghurs], possessed by financial difficulties, hopelessness and psychological breakdown, have become open to various cases of abuse.”83Abdürreşit Celil Karluk, “Uyghur Refugees Living in Turkey and Their Problems,” in Exchange of Experiences for the Future: Japanese and Turkish Humanitarian Aid and Support Activities in Conflict Zones, eds Dündar, A. Merthan and Uygulamalı Bilimler Fakültesi (Ankara: Ankara Üniversitesi Basımevi, 2018).

Kazakh and Uyghur torture survivors experience intense ongoing trauma stemming from their experiences in the Chinese government’s system of camps and the carceral system. After arriving in a host country, many of these survivors do not seek necessary medical treatment out of fear that it will put their families in the Uyghur region in danger. Some choose to keep to themselves, isolated from the wider community.84Bradley Jardine, interview with Aina, audio, September 21, 2022.