A Uyghur Human Rights Project report by Emily Upson. Read our press statement on the report here, and download the full report in English, Bahasa Indonesia, and Melayu.

I. Executive Summary

In February 2019, Chinese government officials released the first-ever proof-of-life video featuring a Uyghur. The recording was an attempt to discredit international news reports that renowned musician Abdurehim Heyit had died in state custody. Hostage-style proof-of-life videos featuring Uyghur subjects have proliferated in the two years since. This report identifies and analyzes observable patterns in these state-produced portrayals of missing Uyghurs, arguing that heavily orchestrated proof-of-life videos are not valid proof of Uyghur freedom but instead further proof of Chinese state culpability for atrocity crimes.

The subjects of these proof-of-life videos are often, though not always, the family members of Uyghur activists who live outside their homeland, East Turkistan (AKA “Xinjiang”). What these diaspora activists often have in common is that they are all campaigning or have in the past campaigned for missing relatives in East Turkistan, whom they fear have disappeared into some form of extralegal, extrajudicial state custody. Uyghur activists are motivated by a desire to demand information about the safety, wellbeing, and whereabouts of their relatives and friends. Chinese state media has responded to the activism of some Uyghurs with a proof-of-life video, often as a tool of misinformation, intimidation, and fear.

This report draws from videos and interviews, as well as media, academic, and NGO reports to describe and analyze the themes, impacts, and implications of proof-of-life videos. The introduction describes the features of proof-of-life videos in further detail. Section II describes and analyzes these features in close detail, showing that many of the videos follow observable patterns, which suggests that they are heavily scripted and dictated not by the subjects of the videos themselves. Section III explores the development of these videos over time, noting how the characteristics have evolved in reaction to diplomatic events. Section IV amplifies the stories of those Uyghur activists whose family members have been depicted in proof-of-life videos, exploring the impacts of the videos on the very people they are meant to silence. Finally, Section V situates the deployment of the videos by the Chinese government in Chinese and international law.

The report concludes with targeted recommendations to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), international political actors, and Uyghur activists themselves. We ask that the CCP make public and transparent its records on the whereabouts of detainees, including Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other peoples who are being held in detention centers, internment camps, prisons, forced-labor settings, or under house arrest. This simple step would allow Uyghur activists to know where their loved ones are while also satisfying international norms regarding the safe treatment and well-being of detained individuals.

We recommend that members of the international community take proof-of-life videos seriously as hostage-style videos that attempt to libel and discredit Uyghur activists abroad. In its goal to be a world superpower, the CCP has initiated a drive to present its policies in East Turkistan as positive. The CCP cares about its international reputation, and the international community must leverage this fact to promote positive change.

II. Introduction

State abuse of human rights in East Turkistan has accelerated since Chen Quanguo was appointed as Party Secretary of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) in August 2016.1Adrian Zenz and James Leibold, “Chen Quanguo: The Strongman Behind Beijing’s Securitization Strategy in Tibet and Xinjiang,” China Brief, Volume 17, No. 12, September 21, 2017, https://jamestown.org/program/chen-quanguo-the-strongman-behind-beijings-securitization-strategy-in-tibet-and-xinjiang/ In Spring 2017, under Chen’s guidance, the regional government began a campaign of mass internment. Four years later, the government continues to detain an unknown but almost certainly massive number of Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other Turkic peoples in concentration camps, detention centers, prisons, and other forms of unfreedom.2The numbers are hard to know for certain, but many researchers believe at least one million Uyghurs may be detained for re-education. Jessica Batke, “Where Did the One Million Figure for Detentions in Xinjiang’s Camps Come From?” ChinaFile, January 8, 2019, https://www.chinafile.com/reporting-opinion/features/where-did-one-million-figure-detentions-xinjiangs-camps-come

Proof-of-life videos, which are filmed under duress and/or coercion, are tools of harassment, threat, and intimidation. These videos and the broader policies from which they emanate violate a number of international rights standards, including the right to family unity.

The state euphemistically labels these policies as “re-education” and “poverty alleviation,” claiming that Uyghur and other detainees must be cleansed of religious extremism and terrorist potential. “Terror” is merely a pretext the government can use to consolidate its power.3Using “terrorism” to justify increasing state control is well documented, and has led to the OHCHR No. 32 factsheet addressing these concerns. “Human Rights, Terrorism and Counter-terrorism,” Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, July 2008, https://www.ohchr.org/documents/publications/factsheet32en.pdf Survivors have testified that torture and unusual cruelty take place within the detention centers. They have also provided evidence of forced sterilization and birth control, leading experts to suggest that the CCP’s actions might legally constitute a genocide of an ethnic group who would not conform to state expectations.4Scott Simon and Adrian Zenz, “China Suppression Of Uighur Minorities Meets U.N. Definition Of Genocide, Report Says,” NPR, July 4, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/07/04/887239225/china-suppression-of-uighur-minorities-meets-u-n-definition-of-genocide-report-s. Note: as this report was in the final stages of publication, the U.S. State Department determined that China committed genocide and crimes against humanity targeting Uyghurs and other Turkic groups in East Turkistan, see: https://2017-2021.state.gov/determination-of-the-secretary-of-state-on-atrocities-in-xinjiang//index.html Leaked documents have shown that being related to someone deems “infected” by dangerous thoughts, such as separatism or extremism, can also threaten one’s individual freedom.5Austin Ramzy and Chris Buckley, “‘Absolutely No Mercy’: Leaked Files Expose How China Organized Mass Detentions of Muslims,” The New York Times, November 16, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/11/16/world/asia/china-xinjiang-documents.html

Following the disappearances of their family members in East Turkistan, many Uyghurs in the diaspora have become activists, using social media, traditional print media, and other tools to advocate for their missing loved ones. International governmental bodies and news media have directed attention to the issue of China’s atrocity crimes, including the amplification of Uyghur activists’ stories. In select cases, Chinese authorities have responded by producing proof-of-life videos featuring missing loved ones. Proof-of-life videos, which are filmed under duress and/or coercion, are tools of harassment, threat, and intimidation. These videos and the broader policies from which they emanate violate a number of international rights standards, including the right to family unity.

What Is a Proof-of-Life Video?

The term “proof-of-life” typically refers to evidence used to prove that a kidnapping victim is still alive. In an international context, proof-of-life usually applies to videos made of piracy victims or prisoners of war. Proof-of-life videos seek to do two things: first, to “prove” that the hostage is alive, and second, to send a message, whether a threat, a negotiation, or an assurance. The kidnappers are generally less concerned with truth than with the message they hope to convey.

One famous, recent example of a proof-of-life video featured U.S. citizen Kayla Mueller, who was abducted by ISIS in August 2013. In the spring of 2014, her captors released a video, audio file, and photographs of Mueller as they attempted to negotiate with her family and the U.S. government. In the proof-of-life video, Kayla claimed to be fine and healthy, a point that seemed to be confirmed by photographs depicting her. The reality only came to light later: while in captivity, she was forcibly married to a senior Islamic State figure, and repeatedly raped and tortured.6Adam Goldman and Greg Millar, “Leader of Islamic State used American hostage as sexual slave,” The Washington Post, August 14, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/leader-of-islamic-state-raped-american-hostage/2015/08/14/266b6bf4-42c1-11e5-846d-02792f854297_story.html

This report applies the term “proof-of-life video” to a novel context: Chinese state media-released videos featuring Uyghurs whose family members abroad have reported them as missing and launched campaigns in their names. These proof-of-life videos are stylized and manipulated, rarely show the hostage in constraints, and in the last section often issue “a plea” to stop campaigning.

Basic Characteristics of Proof-of-Life Videos

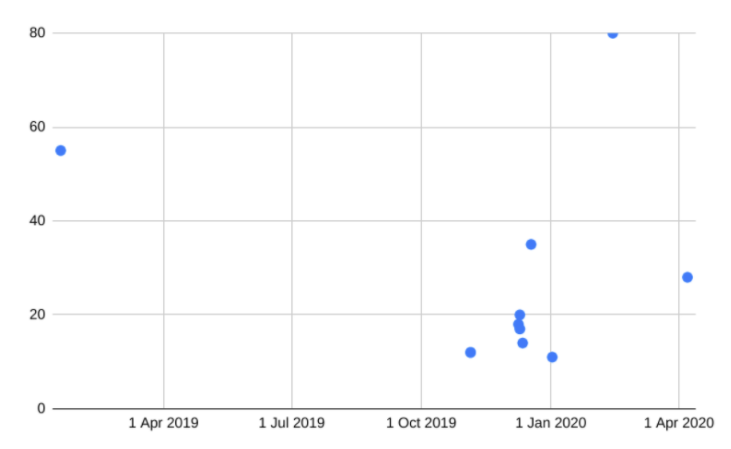

Proof-of-life videos of Uyghurs in Chinese state media first entered the public arena in early 2019. They have evolved since then, increasingly sharing distinctive characteristics that demarcate them as a phenomenon. The videos appear reactive, suggesting the CCP is carefully watching its international reputation and responding tactically. The emergence of proof-of-life videos has given Uyghurs around the world hope that through advocacy efforts, they may pressure the CCP into showing their missing relatives alive.

Many proof-of-life videos are portrayed as real-time investigations by Chinese state media, and even include candid shots of news crews discussing their investigation. However, the state media outlets that produce these videos are not in a position to deviate from the state narrative, regardless of what they find. There can be no credibility in these “investigations” given their eclipsing conflict of interest.

Many proof-of-life videos are purposefully portrayed as reactionary, real-time investigations by Chinese state media, and even include candid shots of news crews discussing their investigation.

Over time, as the sheer volume of testimonies increased, the Chinese state has tended to abandon or underplay the tactic of portraying the testimonials of overseas relatives as intentional lies. State media accounts have suggested that shadowy Western forces, Western media sensationalism, and/or plots to ruin the lives of happy Uyghurs in China are behind these testimonies. However, these videos rarely address alternative explanations for overseas testimonies, perhaps because it seems so outlandish that all of these testimonies would have alternative explanations. The reporting largely fails to account for the motivation behind overseas advocates’ supposed malice.

These videos are likely carefully arranged and curated to get the exact media product most beneficial to the CCP, including scripted speech. Many of the featured Uyghurs recite what might indicate a free life, listing quite disparate claims without any natural breaks in speech. Some parents seemingly have cold or irritated responses to their children’s concerns, with some even expressing sadness only in disappointment at “unpatriotic” acts (i.e., their relatives’ public advocacy).

The videos follow formulaic characteristics. They are often introduced as investigatory and spontaneous, yet the subjects frequently make unrelated statements which directly dispel accusations against the CCP, in what seem like prepared speeches. The pattern suggests that they have been heavily orchestrated. This report will examine how and offer preliminary explanations as to why. It will also consider the impact of these videos on the Uyghurs abroad whose activism has inspired them.

III. Methodology

This report describes a primary data set of 22 proof-of-life videos, which we have analyzed to elucidate a formula described in detail in Section II.7For a complete list of these videos, see Appendix B. These videos originate from Chinese state media outlets and respond to the work of Uyghur activists abroad. The data set includes two videos about deceased individuals, Mutalip Nurmehmet and Nurmehmet Tohti. These videos aim not only to prove the two men’s deaths as unsuspicious, but also to show that their family members are alive and free.

The report also draws from original interviews with activists Ferkat Jawdat, Arafat Erkin, Memet Tohti Atawulla, Gulzire Tashmemet, and Aziz Sulayman to explain and analyze the role that Uyghur activists abroad play in provoking the Chinese government to produce and release proof-of-life videos, as well as what kinds of impacts those videos have on the activists in turn.8Aziz Sulayman has not received a proof-of-life video of any of his relatives but has campaigned frequently with the hope of receiving one.

Additionally, the research references a number of secondary sources, including online interviews and personal accounts from many activists detailing their experiences, as well as print, digital, broadcast, and social media.

We have excluded the following types of videos from the dataset for this report: 1) videos in which the hostage cannot be verified; 2) videos accidentally or coincidentally proving that missing Uyghurs are alive; 3) videos in which the Uyghur person in question is unknown internationally; and 4) a group of 13 videos responding to the #StillNoInfo hashtag campaign, because the provenance of these videos is not clearly a state media organization. These (and other) types of hostage-style videos will warrant close description and analysis in future research to more fully understand the nature of Chinese disinformation regarding the Uyghur crisis.

IV. Video Formula

The proof-of-life videos described in this report share a number of typical elements, which in sum comprise a formula to which many videos at least partially adhere.

Cultural Grounding

Proof-of-life videos often feature material objects, artistic culture, and other practices associated with Uyghur culture. The cultural grounding of these videos is likely rooted in the Chinese government’s desire to appear as though it protects Uyghur culture, a claim which government representatives often make in official statements. Erasure of Uyghur culture in East Turkistan is well-documented, where authorities repress Uyghur religious-cultural practice, foodways, artistic expression, decor, dress, and language.9Yasmeen Serhan, “Saving Uighur Culture From Genocide,” The Atlantic, October 4, 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2020/10/chinas-war-on-uighur-culture/616513/ For many decades, and particularly since 2016, the CCP has focused attention on what happens in Uyghur families, going so far as to dispatch more than one million ethnic Han cadres to homes. Dr. Darren Byler has called this a form of “violent paternalism.”10Darren Byler, “Violent Paternalism: On the Banality of Uyghur Unfreedom,” The Asia-Pacific Journal 16:42 (2018), 1-13. The persistent presence of Uyghur culture in proof-of-life videos may be in response to evidence of state-led cultural erasure.

For example, cultural items including decorations and food are often in the background of proof-of-life videos. The inclusion of such objects of material culture is interesting given that the state undertook a push to “Sinicize” Uyghur homes in January 2020 (and earlier), in part by removing the rugs and wall-hangings that are proudly staged in many of these videos.11Radio Free Asia, “Uyghurs in Xinjiang Ordered to Replace Traditional Décor With Sinicized Furniture,” Radio Free Asia, January 9, 2020, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/furniture-01092020165529.html Zumrat Dawut, whose own family has been the subject of a proof-of-life video, states she was forced to comply with similar measures as early as 2018. Yet, in the proof-of-life videos we reviewed, most families sit in visibly Uyghur homes.

The cultural grounding of these videos is likely rooted in the Chinese government’s desire to appear as though it protects Uyghur culture, a claim which government representatives often make in official statements.

Each frame in the proof-of-life video featuring Abudukerim Abdureyim, a retired 47-year-old from Ürümchi, is adorned with family décor. The accompanying article carefully describes the “typical Uyghur decoration” in the shots “with elegant wallpapers and carpets,” suggesting that the culturally coded backgrounds are not a coincidence.12Shan Jie and Zhao Juecheng, “Allegedly ‘missing’ Uyghurs found living normally,” Global Times, December 23, 2019, https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1174468.shtml Several overlay shots show other cultural markers, such as mealtimes, cooking, and bedding. Several men are wearing doppas, the skull caps Uyghur men often wear. In another video, Memet Tohti Atawulla’s family shares nan (flatbread) on a decorated dining room table, and in another Zharqynbek Otan’s neighbor gives an interview while arranging his pillows and sheets.

The subjects of some other videos emphasize that they live in a healthy and caring economy, for example, by discussing the local community helping in farming labor, education costs, or medical care.

Two grandchildren of Rebiya Kadeer, a prominent Uyghur activist living in the United States, also appeared in a proof-of-life video, with one granddaughter claiming that they taught Uyghur dancing to their Han classmates for fun as she demonstrates Uyghur dancing for the camera.13Granddaughters refute Rebiya Kadeer in exclusive interview with Global Times,” Global Times, January 10, 2020, https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1176379.shtml The other granddaughter claims to study so she can contribute to Uyghur medicine. They reiterate that they “can go to mosques to pray anytime.” The granddaughters’ insistence surely comes from the allegation that Uyghur identity, including religious practice, is heavily restricted and, in some cases, criminalized in the region.14“Sacred Right Defiled: China’s Iron-Fisted Repression of Uyghur Religious Freedom,” Uyghur Human Rights Project, April 2013, https://docs.uhrp.org/Sacred-Right-Defiled-Chinas-Iron-Fisted-Repression-of-Uyghur-Religious-Freedom.pdf

Claims of Financial Stability

Proof-of-life videos featuring Uyghurs often include statements about the financial stability of the featured subjects. These videos claim there is financial recompense for Uyghur labor, perhaps in an effort to refute allegations of forced labor, as well as to refute the broad evidence base that Uyghur forced labor is prevalent in and outside East Turkistan.15Adrian Zenz, “Beyond the Camps: Beijing’s Grand Scheme of Forced Labor, Poverty Alleviation and Social Control in Xinjiang,” SocArXiv, July 12, 2019, https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/8tsk2/ Claims of financial stability are often paired with “gratitude” directed to the CCP for allowing such financial growth, either personally or for the general community.16For a discussion of what scholar Emily Yeh calls “indebtedness engineering,” see Taming Tibet: Landscape Transformation and the Gift of Chinese Development, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2013), esp. Chapter 7 (231-63).

In the videos reviewed for this report, the family of a number of Uyghur activists abroad make this point. The father of Kuzzat Altay mentioned earning a ¥4,000 (US$613) pension; Mahire Eziz’s parents have a ¥5,300 (US$812) monthly pension; and Tayir Ablat, the cousin of a Uyghur activist abroad, saved ¥20,000–30,000 (US$3,063–$4,594) from his job in a restaurant.17Shan Jie and Zhao Juecheng, “Allegedly ‘missing’ Uyghurs found living normally,” Global Times, December 23, 2019, https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1174468.shtml Each of these individuals notes these specific details during addresses to long-lost activist relatives abroad or to the anonymous strangers who have “spread lies” about their being detained, which seems unnatural and further suggests that the interviewees have been given specific directions before filming.

The subjects of some other videos emphasize that they live in a healthy and caring economy, for example, by discussing the local community helping in farming labor, education costs, or medical care. Samira Imin’s father discusses the “rapid development of China,” and Rebiya Kadeer’s granddaughters discuss the region’s fast development while highlighting all the luxury and other clothing brands available in an upscale Ürümchi shopping mall.

There are many allegations of China imposing arbitrary financial restrictions and repercussions against Uyghurs. For example, an individual’s failure to comply with “terror-policing” requirements can result in the state apparatus seizing land and material possessions.18Radio Free Asia, “Uyghurs Face Seizure of Land, Personal Property Under Tough New Rules,” Radio Free Asia, December 17, 2014, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/restrictions-12172014152720.html Scenes filmed with Zharqynbek Otan’s father, Otan Aixilahong, and Aziz Isa Elkun’s mother, Hepizem Nizamidin, use small farms as the setting, implying home ownership and financial stability.

The video featuring Rozi Memet Atawulla includes the claim that he is earning ¥2,500 (US$383) a month, but his brother and advocate, Memet Tohti Atawulla, revealed in an original interview for this report that Rozi earned more before his new “skills training” by selling fruits and cooked meals in the marketplace. The financial declarations in these videos are often mixed with gratitude or reliance on the state. Arafat Erkin’s mother addresses him directly in her video, saying that he could not have studied abroad “without a strong motherland on [his] back,” implying that education is a form of prosperity that requires gratitude in return.

Establishment of Normalcy

Many of the proof-of-live videos in our dataset contain checklists of often unrelated items, all of which are intended to bolster the idea that the Uyghurs featured in these videos are living “normal” lives—specifically, in contrast to the claims their relatives have been making abroad. These checklists are often non-sequitur: the items are generally unrelated to one another, and they attempt to establish “normalcy” in a very abnormal manner.

The clearest example of such a checklist is from the video featuring Rozi Memet Atawulla, who stares off-camera and recites: “I work eight hours now every day. My salary is 2,000 to 2,500 yuan [US$306–$383] a month. During my spare time I like to play basketball. I also like to have dinner with my girlfriend. We have known each other for four or five years. Yesterday we got married.” Given the emotional subject matter, this list appears to be heavily prompted, if not outright scripted.

Abdukerim Abdureyim tells viewers that he likes to water his plants, and, as if to prove it, proceeds to water the plants.19Shan Jie and Zhao Juecheng, “Allegedly ‘missing’ Uyghurs found living normally,” Global Times, December 23, 2019, https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1174468.shtml In the same video, Mahire Eziz’s grandfather also recites some sentences that do not flow naturally from one to the next: “I am retired. I used to work at the water conservancy department. I am 63-years-old. My pension is 5,300 yuan [US$812]. Our life is very good now, and we are very happy.”

Additional examples of seemingly unsolicited assertions of living a good and “normal” life include the following:

- “Our life here is great, our life is getting better and better.”

Rebiya Kadeer’s eldest son even offers to the camera the toneless statement that “the government never oppresses us.” Gulgine Tashmemet, whose sister Gulgine has tearfully advocated for her on social media, smiles at the camera and explains that the weather has been nice recently.20China Daily (@ChinaDaily), “In a recent PBS documentary, Gulziyan Taxmamat, a member of “World Uyghur Congress”, claimed that her sister was detained after returning to China. In fact, her sister, Gulgina Taxmamat, now teaches English at a training institution and lives with her family. #Xinjiang,” Twitter, May 5, 2020, https://twitter.com/chinadaily/status/1257558142847717377

These are all unnatural professions of “natural” life. At best, these awkward assertions suggest that these responses are heavily doctored and that the proof-of-life video subjects are not speaking freely. The statements hint at how artificial the performance of a “very happy” life is.

Emotional Reveal

These videos do not always discuss the allegations of the disappearance, detention, or other persecution of the missing person. Arafat Erkin’s mother never addresses these allegations and instead asks her son to stop speaking out. Gulgine Tashmemet, who speaks about living normally, never directly addresses her sister Gulzire’s concerns about her disappearance. However, these videos often include a moment when the featured Uyghurs talk about their sadness, anger, or confusion.

Several proof-of-life videos choreograph the dramatic reveal on camera. Aziz Niyaz and his wife are featured in three videos. In a video from CGTN, they “reveal” in real time that “their older daughter, Mahire, has been doing something her family couldn’t quite understand,” referring to her advocacy after the reporter “showed Niyaz and his wife what their daughter had posted.”21Aziz Niyaz and his wife were in three proof-of-life videos, this section refers to the second video. “Misinformation in Xinjiang: CGTN tracks down allegedly missing couple in Aksu,” CGTN, December 30, 2019, https://news.cgtn.com/news/3167444d344d4464776c6d636a4e6e62684a4856/index.html They describe their response as “silence at first . . . and then, came the tears.” Her father asks her to get in touch with him, and the report ends by describing “a desperate appeal from a heartbroken parent.”

At best, these awkward assertions suggest that these responses are heavily doctored and that the proof-of-life video subjects are not speaking freely. The statements hint at how artificial the performance of a “very happy” life is.

These emotional reveals appear to attempt to hurt the activist they are addressed to, attempting to belie guilt, shame, or culpability. Some videos do so more overtly than others. In his proof-of-life video, Kuzzat Altay’s father is reclined, emotionless and looking unwell, as he indifferently states, “Kuzhati [sic] has done bad things . . . for this I disown him.” Iminjan Seydin states, “I was heartbroken.” Memet Tohti Atawulla is described as “an unspeakable scar” in the article, but in the video, the only emotional output is his brother’s silent tears.

These relatives may be heartbroken, furious, or apathetic, but the more chilling reality is that they have likely been forced or pressured to relay these messages.

Character Assassination

Character assassination occurs often in proof-of-life videos. For example, a video featuring the family of Sayragul Sauytbay—a Kazakh woman who fled China after being forced to work in a camp—appears to be a blatant attempt to discredit her character. One of Sayragul’s colleagues appears in this video to criticize Sayragul for not being a real doctor and lying about it. Sayragul’s sister accuses her of cheating her financially. Her relatives also criticize her for her testimony on her mistreatment in detention, claiming that she was never missing. Other clips accuse Sayragul of a variety of faults, some of which are irrelevant to her testimony. Several interviews exclaim phrases such as “you area liar,” “you big liar,” “you cheated us,” and “I hate her!” The ad hominem attacks constitute the majority of the video, but significantly, they do not counter Sayragul’s claims.

Other interviewees accuse Sayragul Sauytbay of having “altered worksheets to increase her own income while deducing the wages of her colleagues” or of not letting children go to the bathroom. One interviewee claims, “sometimes she beats [the children]” and “sometimes she does not give [them] food,” and one man, apparently solicited for sex by Sayragul, sobs while he confesses, “I heard that she took many lovers.” The end of the clip includes these shocking lines:

“Sayragul Sauytbay abused young children. She defrauded loan and had a bad lifestyle. She is a person with no moral standard who lies all the time. How could she receive the International Women of Courage Award? Do you Americans always judge women this way? This award for her is an insult to the development of Women’s rights. Sayragul Sauytbay is a degenerate member of all women. She is a real scumbag!”

Some character assassinations are more subtle than this. The article accompanying the video of Aziz Isa Elkun’s father notes, “Aziz did not return for his Father’s funeral, so he had no idea about the burial site.”22Wang Xiaonan and Wang Zeyu, “CGTN Exclusive: Tracking down relocated Uygur graves in China’s Xinjiang,” CGTN News, January 13, 2020, https://news.cgtn.com/news/2020-01-11/CGTN-Exclusive-Tracking-down-relocated-Uygur-graves-in-NW-China-Nak37jfg1G/index.html A video on Mutalip Nurmehmet’s death claimed that it was alcohol consumption, not state detention, that killed him and that he was given the opportunity to stop drinking and save himself.23Given that Uyghurs are forcefully encouraged to drink alcohol, an activity prohibited by Islamic tradition, this is particularly pernicious. Annie Wu, “China Forces Uyghur Muslims to Eat Pork, Drink Alcohol During Lunar New Year,” Genocide Watch, February 10, 2019, https://www.genocidewatch.com/single-post/2019/02/09/China-Forces-Uyghur-Muslims-to-Eat-Pork-Drink-Alcohol-During-Lunar-New-Year Businesswoman and rights activist Rebiya Kadeer’s grandchildren suggest she is too old and insecure to appreciate the rapid changes of a new city.

Interestingly, the proof-of-life video of Ferkat Jawdat’s mother is accompanied by an article which claims his mother called him a “scumbag.” Ferkat, who reports having had some supervised phone calls with his mother in recent years, feels confident she does not feel this way. In an interview with UHRP, he recalled joking with her, “Did you really call me a scumbag? I’m not that bad, now, come on.” She did not laugh back, he said, and instead became angry, as she had not known that this is how the article described her. She reportedly told him how proud she was to have him in their family and then questioned the local police to their faces.

The proof-of-life video made in response to Zumrat Dawut’s activism was accompanied by an article that asserted that her brother “thought his father’s physical conditions worsened partly because he missed Zumrat very much,” and that their “father grieved as she left without telling him.” Of course, this may also not be true.

Final Pleas

Final pleas are a highly revealing component of the proof-of-life video genre, as these calculated maneuvers allow for insight into what messages the videos are attempting to convey. In many cases, the videos are intended to function at least partly as a direct threat to activists lest they “break” the “beautiful lives” of their loved ones. Some examples of such pleas include the following:

- “Brother, please do not break our beautiful life.” (Memet Tohti Atawulla’s brother)

- “Don’t be deceived by overseas anti-China forces again and stop saying those things.” (Samira Imin’s father)

- “Sister, do not listen to the rumour.” (Mahire Eziz’s brother Yusup, reported in the accompanying article)

- “Stop making up lies with my husband. I hope you stop the lie.” (Mutalip Nurmehmet’s wife)

- “If you don’t believe me, you can see it in Xinjiang with your own eyes.” (Rebiya Kadeer’s son)

- “Think twice, and you are a wise man. Come home.” (Ferkat Jawdat’s uncle)

- “Dear sister, no more lies.” (Zumrat Dawut’s brother)

- “You should study hard and honor the country in the future.” (Arafat Erkin’s mother)

- “Please do not share lies and affect our good lives.” (Abdukerim Abdureyim, reported in the accompanying article)

- “Come back quickly. Come back to pay your loan. You liar!” (Sayragul Sauytbay’s friend)

- “I don’t know why she would make up such stories about us. We live very well. If she really cares about us, or misses us, we ask her, please just contact us.” (Mahire Eziz’s father)

These seemingly innocuous lines are threats: Uyghur activists know that to contact their families would mean trouble and that to return themselves would mean certain incarceration, if not worse. Rebiya Kadeer’s video showed her son explicitly inviting her home. Yet, text at the end of the video claims, “[i]n interviews with the Global Times, Rebiya Kadeer’s relatives said that they want her to stop spreading rumors and do [sic] not disturb their peaceful life anymore [sic].” This emphasis on freedom to return is particularly concerning given that many returning expatriates have their passports revoked, meaning there is no freedom to leave again.

These seemingly innocuous lines are threats: Uyghur activists know that to contact their families would mean trouble and that to return themselves would mean certain incarceration, if not worse.

Over the past several years, Uyghurs outside East Turkistan have documented numerous instances of CCP officials threatening them to return to East Turkistan, using the freedom and wellbeing of local relatives against them.24Eva Dou, “China’s Muslim Crackdown Extends to Those Living Abroad,” Wall Street Journal, August 31, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-muslim-crackdown-extends-to-those-living-abroad-1535718957 Similarly, it appears that authorities coerce the subjects of proof-of-life videos to encourage their overseas family members to be silent, compliant, and to return home.

The tactics used in these videos exploit activists’ vulnerabilities against themselves and potentially affect future campaigners. The most difficult part of activism is always the choice to risk speaking out, and these videos both discourage and encourage relatives abroad to make that choice. The Uyghurs depicted in proof-of-life videos may be under threat, but their relatives now know they are alive.

V. Evolution of Proof-of-Life Videos

Abdurehim Heyit Hostage Video

Over time, proof-of-life videos have evolved in terms of length, content, and focus. The first proof-of-life video was the February 2019 “hostage” video of beloved musician Abdurehim Heyit, which does not follow the basic patterns observed in later videos. Still, it is critical to examine this video because of its role as the first such media to emerge from the ongoing repression.

Abdurehim Heyit is a renowned singer, musician, and composer known for his virtuosic playing on the dutar, the two-stringed lute foundational to Uyghur music culture. Mr. Abdurehim’s repertoire include folksongs from around the Uyghur region along with original compositions that set early-20th century nationalist poetry to music. One such composition is his “Atilar” (“Fathers”), which encourages respect for ancestral sacrifice and references the “martyrs of war.”25John Sudworth, “Turkey demands China close camps after reports of musician’s death,” BBC News, February 10, 2019, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-47187170 In 2017, Abdurehim Heyit was sentenced to eight years in prison, reportedly for this act of “terrorism.”

After rumors of Abdurehim Heyit’s death circulated online in February 2019, Turkey’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs confirmed his death.26Hami Aksoy, “Statement of the Spokesperson of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs,” Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs, February 9, 2019, http://www.mfa.gov.tr/sc_-06_-uygur-turklerine-yonelik-agir-insan-haklari-ihlalleri-ve-abdurrehim-heyit-in-vefati-hk.en.mfa This confirmation provoked China Radio International’s Turkish-language service to release a proof-of-life video on Twitter that claimed that Turkey’s criticisms were unfounded.

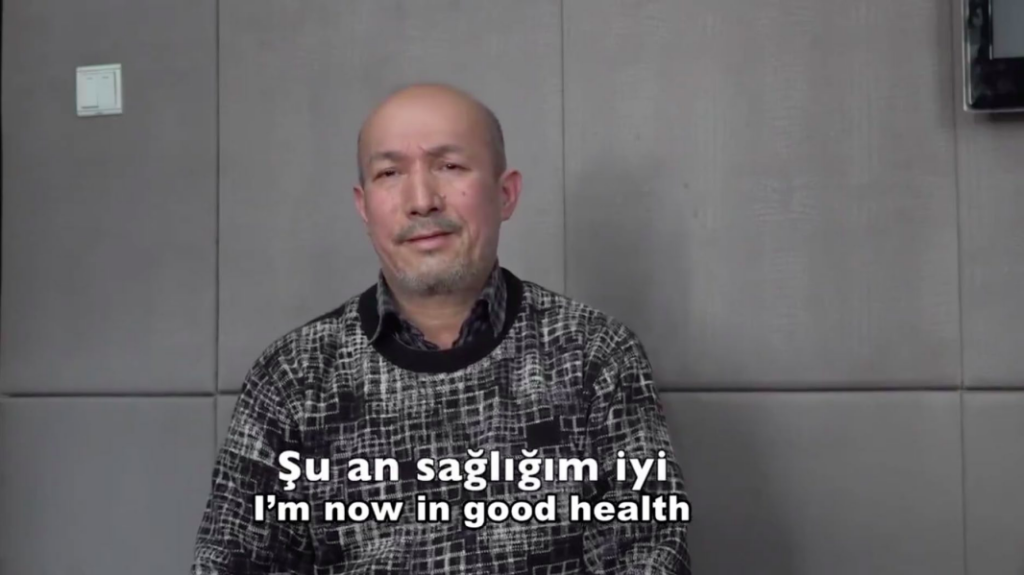

The content of the video is limited. In it, Mr. Abdurehim merely states:

“My name is Abdurrehim [sic] Heyit. Today is February 10, 2019. I’m in the process of being investigated for allegedly violating the national laws. I’m now in good health and have never been abused.”27CRI Türkçe (@CRI_Turkish), “Abdurrehim Heyit ölmedi, Türkiye Dışişleri’nin #Xinjiang iddiaları asılsız. Abdurrehim Heyit’in sağlık durumunun iyi olduğu açıklandı. https://youtu.be/q_Y0CbFWoUo @TC_Disisleri @TurkEmbBeijing @anadoluajansi @trthaber @ntv @cnnturk @Hurriyet @Postacomt #AbdurrehimHeyit,” Twitter, February 10, 2019, https://twitter.com/CRI_Turkish/status/1094606833061228549?s=20

Large grey panels appear on the wall behind him, and Abdurehim Heyit sways his torso in small, controlled circles, blinking repetitively. His head and face are shaven, and his face is stoic. Abdurehim Heyit’s appearance and movements are similar to patterns in other forced confessions televised in China since 2013, as collated by Safeguard Defenders.28“’My hair turned white’: report lifts lid on China’s forced confessions,” The Guardian, April 12, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/apr/12/china-forced-confessions-report

As discussed above, this kind of non-sequitur checklist has remained a prominent feature in proof-of-life videos, suggesting that these videos are scripted. Magnus Fiskesjö, Associate Professor of Anthropology at Cornell University, tweeted that the video felt like “a Chinese [government] forced TV confession, typically used on people with a voice: They are disappeared and coerced by police torturers to self-incriminate on TV [and] to pretend they’re OK.”29Magnus Fiskesjö (@Magnus_Fiskesjo), “The tone, unspecified location, backdrop, ambiance…,” Twitter, February 10, 2019, https://twitter.com/Magnus_Fiskesjo/status/1094625234324545536

In an interview, Nury Turkel alleged that elements of the video were “suspicious,” and that the onus of proof was on China.30“Abdurehim Heyit Chinese video ‘disproves Uighur musician’s death’,” BBC News, February 11, 2019, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-47191952 A pro-China Turkish media outlet reported that Abdurehim Heyit was detained for only two weeks,31“Aydınlık, ‘Öldürüldü’ denilen ünlü Uygur ozan Abdurrehim Heyit ile görüştü,” Aydinlik, July 25, 2019, https://www.aydinlik.com.tr/aydinlik-olduruldu-denilen-unlu-uygur-ozan-abdurrehim-heyit-ile-gorustu-turkiye-temmuz-2019-6 and then lived under house arrest, but at the time of publication of this report, there has been no clear news of his whereabouts.32“Abdurehim Heyt,” Xinjiang Victims Database, accessed August 27, 2020, https://shahit.biz/eng/viewentry.php?entryno=411

While the Foreign Ministry and state media are responsible to different departments, they are both parts of the same government, and as such we might read this as an extension of the same message: do not accuse China of human rights abuses.

The Abdurehim Heyit proof-of-life video arguably worked against China by only further provoking the state’s critics, leading to activist-led hashtag campaigns such as #MeTooUyghur and #MenmuUyghur, in which overseas Uyghurs demanded proof-of-life videos of their missing relatives. Instead of quelling criticism, the video has seemed only to invite it.

According to Alip Erkin, an Australia-based Uyghur activist, Abdurehim Heyit “seemed distressed in the video as if he was having trouble finding his next words to say with trembling lips. That is not the Abdurehim Heyit we have known.” Alip Erkin also added that the post “should be evidence of [Abdurehim Heyit’s] wrongful and secret detention for expressing Uygur values in his songs, not as some sort of diplomatic victory for China.”33Nectar Gan, “China releases video of ‘dead’ Uygur poet Abdurehim Heyit but fails to silence critics,” South China Morning Post, February 11, 2019, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/2185695/china-releases-video-dead-uygur-poet-abdurehim-heyit-fails

A variety of news sites heavily dissected the video, as well. The Guardian, Quartz News, ABC News, Al Jazeera, and Financial Times all released articles about the video, critical of what it revealed about China’s treatment of Uyghurs in the region.34“Sentenced to 8 years of prison for “separatism”,” World Uyghur Congress, November 2019, https://www.uyghurcongress.org/en/aburehim-heyit/; “’I have never been abused’ says detained Uighur Abdurehim Heyit,” The Guardian, February 11, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/global/video/2019/feb/11/i-have-never-been-abused-says-detained-uighur-abdurehim-heyit-video; Steve Mollman, “Watch: the musician Turkey mourns in its protest of China’s Uyghur detention camps,” Quartz News, February 10, 2019, https://qz.com/1546888/watch-the-musician-whose-death-in-chinas-uyghur-detention-camps-helped-sparked-turkeys-protest/; Erin Handley and Michael Li, “’Dead’ Uyghur poet Abdurehim Heyit appears on Chinese state media, says he’s ‘never been abused’,” ABC News, February 11, 2019, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-02-11/chinese-state-video-tape-of-uyghur-musician-reported-dead/10798536; Turdi Ghoja, “The jailed folk singer at the front line of the Uighur struggle,” Al Jazeera, March 16, 2019, https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2019/3/16/the-jailed-folk-singer-at-the-front-line-of-the-uighur-struggle/; Yuan Yang and Laura Pitel, “China condemns ‘absurd lies’ about detained Uighur musician,” Financial Times, February 11, 2019, https://www.ft.com/content/f7b243a6-2dcb-11e9-ba00-0251022932c8 Amnesty International researcher Patrick Poon made a personal statement that it was “unclear when and where Abdurehim Heyit took the video,” and that genuine proof could be achieved by allowing him “to talk to his family, friends and journalists directly, without any interference.”35

At a press conference on February 11, 2019, Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) spokesperson Hua Chunying commented she had also watched the Sunday video clip.36Gan, “China releases video of ‘dead’ Uygur poet Abdurehim Heyit.” Proof-of-life videos are politically orchestrated releases of information. However, Chinese media personalities and diplomats will act as if they are surprised by the revelations. Hua stated that she “hope[d] relevant Turkish persons can distinguish between right and wrong and correct their mistakes.” Hua also said the video proved Heyit “is not only alive but also in very good health. The Turkish authorities’ unfounded accusation against China, based on the lie about the false death, is extremely wrong and irresponsible.” While the Foreign Ministry and state media are responsible to different departments, they are both parts of the same government, and as such we might read this as an extension of the same message: do not accuse China of human rights abuses. This basic message continues through the proof-of-life videos.

Mihrigul Tursun Video

Proof-of-life videos are often provoked by international political and media attention. This point is observable in the second proof-of-life video made for Mihrigul Tursun. In November 2018, Ms. Mihrigul testified at the National Press Club and to the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, both in Washington, DC, recalling that she had been held in camps where detainees were tortured and abused. When she was detained, she was separated from her three baby triplets. She testified that one of her triplets died, and the other two of the triplets developed health problems that she believed to have originated in state custody. Her testimony includes the chilling line, “I thought that I would rather die than go through this torture and begged them to kill me.”37Cagan Koc, “China Denies Turkish Claim That Uighur Poet Died in Xinjiang,” Bloomberg News, February 11, 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-02-11/china-denies-turkish-claim-that-uighur-poet-died-in-xinjiang

Mihrigul Tursun’s testimony continued to attract international attention into 2019, and in March of that year, CGTN released a proof-of-life video featuring her family.38Watson and Weston, “Uyghur refugee tells of death and fear.” The video predominantly worked to discredit her, claiming that her entire testimony was falsified. Her brother, while tearful, holds up a screenshot from an alleged WeChat conversation between the two of them, which intimates that she gave testimony under coercion. The family is “deeply worried about her condition in the US.”

This particular video attempts to prove that Mihrigul’s relatives are free and that the son she claims died is actually alive. Like many proof-of-life videos, its primary purpose appears not to be proving the family’s version of the truth but rather disproving Mihrigul’s testimony and what it reveals about the broader situation in East Turkistan. Discrediting her as a person is just as relevant to this act as is showing her family “living well.”

Similar to her response to the Abdurehim Heyit allegations, MFA spokesperson Hua Chunying also responded to the Mihrigul Tursun case, claiming that Ms. Mihrigul’s twenty-day custody in the Cherchen (Qarqan) County Police station was justified due to suspicion of inciting ethnic hatred and discrimination, and that she was otherwise free. Hua also denied that Mihrigul Tursun’s child had died.39“Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying’s Regular Press Conference on January 21, 2019,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, accessed August 21, 2020, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/xwfw_665399/s2510_665401/2511_665403/t1631149.shtml

Videos Targeting Ferkat Jawdat, Zumrat Dawut, and Arafat Erkin

On November 5, 2019, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo made a statement denouncing China’s policies toward Muslims. In the statement, he highlighted the stories of three U.S.-based Uyghur activists: Arafat Erkin, Ferkat Jawdat, and Zumrat Dawut.40“Secretary Pompeo’s Meeting with Uighur Muslims Impacted by Human Rights Crisis in Xinjiang,” U.S. Embassy & Consulates in China, March 28, 2019, https://china.usembassy-china.org.cn/secretary-pompeos-meeting-with-uighur-muslims-impacted-by-human-rights-crisis-in-xinjiang/ Arafat Erkin has been advocating for information about his missing father since late 2018, while Ferkat Jawdat has been advocating for his mother since September 2018. Zumrat Dawut is a camp survivor who sought refuge in the United States after spending a period in an internment camp, where she faced detention, sterilization, and mistreatment. She has given testimonies widely since her arrival to the U.S. in 2019.

Barely two weeks later, on November 17, Global Times responded with a three-part video. Each part focused on each activist’s family. At this point, proof-of-life videos became more firmly established as a genre: the formulaic construction was evident even between each of the three parts of the video, and these patterns suggested that the contents were highly orchestrated.

Ferkat Jawdat’s mother is “comforted” by the secretary of the residential community, who has become her “relative.”41Residential communities are comprised predominantly by residents, rather than businesses or other facilities, and they are governed by community committees or community institutions. Darren Byler, “Violent Paternalism: On the Banality of Uyghur Unfreedom,” The Asia Pacific Journal 16: no. 24 (2018): accessed August 20, 2020, https://apjjf.org/2018/24/Byler.html. And Darren Byler, “China’s Government Has Ordered a Million Citizens to Occupy Uighur Homes. Here’s What They Think They’re Doing,” China File, October 24, 2018, https://www.chinafile.com/reporting-opinion/postcard/million-citizens-occupy-uighur-homes-xinjiang Arafat Erkin’s mother leans against furniture, reciting, “How are you doing, my child? How is school? We are doing great here, you were born and raised in China.” His uncle joins her, chiming in that “after learning about your shameful deeds, we were so disappointed.” Zumrat Dawut’s family says to Zumrat that she is “making lies,” that she treated her father poorly, that her father’s health “worsened partly” due to her absence, and that his death (in October 2019, after he was allegedly detained) was not suspicious. The erasure of the interview subjects’ autonomy in their own homes, the most intimate and personal of spaces, is a sign of systemic violence and a clear violation of rights.

Media attention can elicit other responses, too, showing that proof-of-life videos are but one way the CCP can be pressured into action. The three activists spoke to Pompeo in person on March 27, 2019, which the U.S. embassy in China published the next day. On Sunday, March 31, Ferkat Jawdat’s aunt was transferred from a prison to a camp, where conditions were better, according to Ferkat Jawdat and his mother. Ferkat Jawdat received calls and messages from his angry and fearful family, who told him that he needed to stop his activism. However, he recognized that the more he spoke out against the CCP, the more he saw an impact. Pompeo’s pressure on this story immediately changed his aunt’s account.42Residential communities are comprised predominantly by residents, rather than businesses or other facilities, and they are governed by community committees or community institutions. Darren Byler, “Violent Paternalism: On the Banality of Uyghur Unfreedom,” The Asia Pacific Journal 16: no. 24 (2018): accessed August 20, 2020, https://apjjf.org/2018/24/Byler.html. And Darren Byler, “China’s Government Has Ordered a Million Citizens to Occupy Uighur Homes. Here’s What They Think They’re Doing,” China File, October 24, 2018, https://www.chinafile.com/reporting-opinion/postcard/million-citizens-occupy-uighur-homes-xinjiang

VI. Activists Targeted

The link between specific activists and proof-of-life videos is anecdotal, but compelling. For many activists, it is almost irrelevant to what extent the relationship can be proven. One Uyghur activist, when asked about whether the CCP can be pressured into action, said, “We [the Uyghurs] don’t need proof. We know.” That strength of conviction may be borne from the murky panic of helplessness. The exhaustion, fear, and relentless reliving of trauma haunts many activists because their campaigning is rooted in the belief that doing so will save their loved ones.

Social Media Campaigns

Immediately after the Abdurehim Heyit proof-of-life video, Finland-based activist Halmurat Harri began a social media campaign called #MeTooUyghur, arguing: “If the Chinese government can prove that Abdurehim Heyit is still alive by releasing a video, the rest of the Uyghur community also deserves to know whether their detained Uyghur compatriots are still alive or not.”43It must also be noted, however, that not every advocate faces such positive effects from their activism. Rushan Abbas spoke at the Hudson Institute on September 5, 2018, entitled “China’s “War on Terrorism” and the Xinjiang Emergency.” Her sister and aunt were subsequently taken just six days later. Abbas is certain this is state retaliation for her activism. For years, Halmurat has been campaigning for his parents’ release by organizing freedom tours of Europe and other campaigns with other activists, including Gulzire Tashmemet.44William Yang, “#MeTooUyghur: The Mystery of a Uyghur Musician Triggers an Online Campaign,” The News Lens, February 14, 2019, https://international.thenewslens.com/article/113718 In an interview with UHRP, Gulzire describes their campaigning work as trying to establish patterns not only in social media but also in the content and scale of protest marches in Berlin. Collective action is an effective way to increase pressure on governments to listen to key concerns.

When it became obvious that the CCP responded to international news and media pressure, many Uyghurs, like Halmurat, saw this as an opportunity to elicit an update on their relatives’ wellbeing. Uyghur expatriate Bahram Sintash tweeted about his missing father, retired editor Qurban Mamut: “I still have no info about my 70 years old father […] I’m starting to think he might be already dead.”45Halmurat Harri, “How Can I Stay Silent: The Story of My Activism”, Uyghur Aid, May 12, 2019, https://uyghuraid.org/blog/2019/05/12/the-story-of-my-activism Shortly after, Sintash created the #StillNoInfo campaign and concerned relatives took to social media to demand a “proof-of-life” video for their own relatives. He did this along with the infrequently used hashtag #ProveThe90%, which refers to the apparent 90 percent of Uyghur detainees who have been released following international pressure. Hundreds took to social media, flooding it with testimony. As of January 2021, Bahram Sintash still has no news of his father.46Radio Free Asia, “Chinese Media Campaign to Discredit Movement For Missing Uyghurs Will Fail: #StillNoInfo Founder,” Radio Free Asia, January 6, 2020, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/campaign-01062020144054.html

Many activists have also campaigned by submitting short video testimonies to “Uyghur Pulse,” a YouTube account and companion to Shahit.biz, a database chronicling reports about missing Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and others. Still, many activists have received no news about their families. Activists are stuck in a perpetual state of half-mourning, wondering whether their loved ones are dead or alive. The Australian Broadcasting Corporation called China’s practices on reporting Uyghur wellbeing a kind of “disinformation warfare,” and Uyghur advocates are fighting back by putting their truth into the public arena and demanding information.47Erin Handley, “Safe and sound? China launches propaganda blitz to discredit Uyghur #StillNoInfo campaign,” ABC News, January 17, 2020, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-01-18/safe-and-sound-china-propaganda-undercuts-xinjiang-uyghur/11865648 In a number of cases, their work has provoked responses from China in the form of proof-of-life videos.

Risks and Rewards of Speaking Out

Many expatriate Uyghurs often wait to speak out after losing contact with their loved ones. This should not be a surprise, given the threat that campaigning poses to both activists and their relatives in East Turkistan. Many overseas Uyghurs claim that Chinese state representatives commonly phish for information and take efforts to silence them. Other threats are much more explicit, such as being followed or physically intimidated.48“Nowhere Feels Safe,” Amnesty International, accessed August 20, 2020, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/research/2020/02/china-uyghurs-abroad-living-in-fear/. “Repression Across Borders: The CCP’s Illegal Harassment and Coercion of Uyghur Americans,” Uyghur Human Rights Project, August 2019, https://docs.uhrp.org/pdf/UHRP_RepressionAcrossBorders.pdf Fear from these threats may be combined with the threat of physical repercussions on their missing family members. Potential activists balance the possibility of their story prompting international intervention against the risks of the CCP punishing their relatives or themselves. The predominant threat against activists is against their loved ones in China, often saying “that family members would be detained if they did not return to [East Turkistan] or that they would not be able to see their family again if they refused to provide information about other Uyghurs living in their communities.”49“Nowhere feels safe,” Amnesty International.

Still, many activists have received no news about their families. Activists are stuck in a perpetual state of half-mourning, wondering whether their loved ones are dead or alive.

Aziz Sulayman, who advocates for his brother, Alim, reported during an original interview that he received calls from individuals claiming to be with Chinese embassies asking repeatedly for information or his imminent return to China.50Emily Upson, “The detention of Alim Sulayman and the campaign to save him,” Sinopsis, May 29, 2020, https://sinopsis.cz/en/alim-sulayman/ Aziz shared that he was delighted with these threats because it confirmed his activism was working. Ferkat Jawdat similarly shared the insight that each threat revealed that the CCP felt vulnerable and that his campaigning would keep his mother safe despite the threats. He pointed out that if he did not raise media attention, such as encouraging a New York Times reporter to repeatedly visit his mother, she may have continued to suffer in prison.51Paul Mozur, “A Woman’s journey through China’s detention camps,” New York Times, December 9, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/09/podcasts/the-daily/a-womans-journey-through-chinas-detention-camps.html He suggested that the government acted not out of pity, but fear.

“The scariest thing is deciding to do it. After that, it’s easy,” said Ferkat. Initially, he was silent, as his family was scared for Munawar Tursun’s life, but eventually Jawdat thought there was so little to lose, and the risk became worthwhile. When the government tells him to stop, insults him, and warns him, he feels like he is getting their attention, which reaffirms his resistance. When campaigners like Ferkat know and understand the threats posed, they can sometimes encourage themselves and others to speak out.

Unusual Cruelty

It is not unusual for local authorities within East Turkistan to hold relatives hostage, threatening their quality of life and asking them to silence their advocates on monitored calls. Peter Irwin, Senior Program Officer for Advocacy and Communications at UHRP, describes this phenomenon as “hostage diplomacy, and it’s not just directed at a particular individual,” claiming instead that the overall aim is to silence campaigners from speaking up.52William Yang, “DW interview: Uighur woman remains ‘unfree’ despite release from re-education camp,” DW News, May 19, 2020, https://www.dw.com/en/dw-interview-uighur-woman-remains-unfree-despite-release-from-re-education-camp/a-53493328 This may partially be why character assassinations are so popular in these videos, as they work not only to delegitimize Uyghurs and Uyghur testimony but also to deter others from following their path.

The potential to see missing relatives alive is among the main reasons many Uyghurs persevere in their activism. While many activists are relieved to see their relatives are not dead, they still often find the videos difficult to watch.

The potential to see missing relatives alive is among the main reasons many Uyghurs persevere in their activism. While many activists are relieved to see their relatives are not dead, they still often find the videos difficult to watch. Very few of their relatives are depicted comfortably, and many appear unwell. Other details in the videos confirm news about the broad scale of repression in East Turkistan: a number of the family members claim to be working in occupations that are not their own (suggesting connections to forced labor), men have shaved their heads as well as their beards (suggesting restrictions on religious and cultural expression), and several are unwell or look visibly different from their usual selves (suggesting abuse).

Out of the 22 proof-of-life videos analyzed for this report, five attempt to prove that someone’s relatives are alive. Two of these videos focused on the late Nurmehmet Tohti and Mutalip Nurmehmet, depicting their relatives alive, mourning, and safe. The other three videos focus on the families of escaped detainees who campaigned internationally, including Mihrigul Tursun, Sayragul Sauytbay, and Zharqynbek Otan. Out of these three videos, only Sayragul Sauytbay’s family and friends looked physically healthy.

Out of the other 17, eight look physically healthy, and nine look unwell (although four of these are older relatives, who could have aged rapidly). “Looking unwell” is an evidently subjective statement that here draws from observations on weight loss, dark circles underneath eyes, explicitly declared health problems, and an inability to stand straight or walk freely. Proof-of-life videos frequently reveal the missing individual is alive but unwell, which might indicate undue suffering or even physical distress and suggest that the subject may not be as free as the spoken transcript implies. For prominent Uyghur historian and publisher Iminjan Seydin, a shaved head and creased clothing indicate a marked difference from his previous appearance, and his daughter and campaigner, Samira Imin, is very concerned.53“Daughter of Uyghur Historian Questions Legitimacy of State Media Video Denying His Detention,” Radio Free Asia, May 7, 2020, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/video-05072020181743.html

The cruelty of these proof-of-life videos may result in fear, helplessness, or even inaction for fear the situation may worsen. Nurbiya Ahmattohti and her husband were reported as incarcerated by Radio Free Asia, who interviewed several of their neighbors to confirm they were being held by state authorities. During this time, their son drowned in a nearby ditch and was dug out of an ice wall a day later. Forced to take part in a propaganda video, the parents take blame, which the article justifies with the assertion that “insufficient care” was given. They repeat the government has treated them well. The father speaks the most and claims international media “are interfering with our lives and spreading rumors.” The mother’s only line in the video is “they don’t care how parents of these kids feel at all when telling lies.” While this statement clearly is intended to refer to international media, it seems ironic if these grieving parents are indeed reading a script.

The video depicting Nurbiya Ahmattohti briefly shows other Uyghur families whose children have drowned. The narrator in the video claims none of these parents have been to a “re-education camp,” and that their parenting was merely insufficient. The narrator then claims one allegedly drowned child (without citing the allegations or providing the child’s name) never existed at all. The range of ways this video discredited concerns Uyghur children have died in their parents’ absence were more focused on discreditation than on the wellbeing of these grieving parents or the prevention of children drowning. These varied refutations fit into the pattern of bombarding viewers with alternative explanations casting doubt on the claims Uyghur activists outside of China have been making. The video ends with the somber half-threat “no-one knows whether the slander will cast a further shadow,” as the parents say they plan to spend time with their families.

Cruelty in these proof-of-life videos may encourage terror, helplessness, or even inaction for fear the situation may worsen.

There is also a cruelty imposed upon diasporic Uyghurs watching the videos, who will likely pay close attention to these videos, spot the formulaic patterns emerging, believe the videos are scripted and artificially produced, look for and find frequent signs of illness, and imagine the intense coercion and distress taking place behind the scenes. What most proof-of-life subjects say is directed to their campaigning relatives, but the videos are public, targeting not only Uyghur activists but also the broader Uyghur community around the world.

VII. International Law

The CCP has broken multiple international standards through its administration of East Turkistan. These violations have been detailed in a document published by United Nations independent experts with the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.54“Counter-Terrorism Law of the People’s Republic of China and its Regional Implementing Measures, the 2016 Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Implementing Measures,” (OL CHN 18/2019, UN Special Rapporteurs, 2019). This submission was completely unprecedented, indicating the severity of the situation for human rights experts. The situations depicted in proof-of-life videos violate key tenets of law. This section analyzes the suitability of privacy and defamation statutes, rights to family unity, and protections against “degrading treatment.”

International Standards

Article 12 of the Universal Declaration of Human Right (UDHR) states “[n]o one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honor and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.”55Arbitrary interference is enforced upon Uyghurs by a whole host of policies. It can be seen in the home as described in Byler’s “Violent Paternalism” to change Uyghur culture and the Sanxin Huodong campaign to remove Uyghur decor. Families are interfered with on a mass scale from demographic shifts in detentions, forced marriages, relocations, and child protection centers. This right is also protected by Article 17 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, a covenant China signed in 1998 but has not ratified, the second clause of which affirms the right of everyone “to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.”56“International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,” Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, October 20, 2020, https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/ccpr.aspx

Proof-of-life videos feature allegedly missing Uyghurs speaking about intimate family trauma in their homes, which constitutes an invasion of privacy. That local authorities and state media outlets film these videos under coercion only intensifies the degree of invasion. When the outlet requesting an interview is tied to the government whose own policies are in question, true consent cannot occur—and this says nothing about the culture of fear of arbitrary detention that is also at play. A state investigation into its own practices cannot have empirical value. Moreover, manipulating the testimony (either through stylistic production or actual scripts) and globally distributing these videos contravene this human right.

Many of these videos include sensitive information that might defame their targets: for instance, Mutalip Nurmehmet’s alleged alcoholism or Sayragul Sauytbay’s alleged sex drive. Such statements contravene the privacy of the individual and the family. Abdulla Rasul and Aziz Isa Elkun’s relatives accuse them of being bad family members. Although unlikely to offer Uyghurs practical support, Article 246 of the PRC’s own criminal law prohibits such defamation.57“Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China,” Congressional-Executive Commission on China, March 14, 1997, https://web.archive.org/web/20100803234710/http://www.cecc.gov/pages/newLaws/criminalLawENG.php

Family unity is protected under several human rights instruments. Article 23(1) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights states that “The family is the natural and fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State.” Interestingly, international statutes do not merely protect against state interference in family unity but actively call for its protection. Article 10(1) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights states that “the widest possible protection and assistance should be accorded to the family.” There is no legitimate excuse for keeping loved ones separate: China has before intimated that the fault lies with Uyghurs who cannot fill out the proper paperwork and follow due process, but here the separated family deserves administrative assistance in order to be “protected.”

In the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT), there is no definition of what constitutes degrading treatment. China has signed and ratified this treaty and is obliged to meet its standards. The European Commission notes the lack of a definition and offers its own as a “source of guidance”: “Treatment that humiliates or debases an individual, showing a lack of respect for, or diminishing, their human dignity, or when it arouses feelings of fear, anguish or inferiority capable of breaking an individual’s moral and physical resistance.”58Glossary: degrading treatment or punishment,” European Commission, October 15, 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/networks/european_migration_network/glossary_search/degrading-treatment-or-punishment_en Proof-of-life videos humiliate the activist by using their family against them, debase the missing person by coercing their global performance, and undermine the autonomy of the Uyghurs the government purports to represent.

Many well-documented cases of psychological and emotional harm among Uyghur diaspora have been observed in the United States,59“Repression across borders,” Uyghur Human Rights Project. and in the wider international community.60“Nowhere feels safe,” Amnesty International.

China has attempted to hide gross human rights abuses, intentionally continuing repressive treatment within East Turkistan, but their responses to international media show a preoccupation with their own reputation.

Article 16(1) of CAT observes that state parties “must” prevent degrading treatment when committed by or at the instigation of a public official, meaning that the state is directly contravening this convention. Article 12(1) also notes the obligation of State Parties to ensure that “competent authorities proceed to a prompt and impartial investigation. . .” It is ironic the state media’s “investigations” into the region’s missing Uyghurs constitute degrading treatment.

China’s Ambition

There have been diplomatic actions taken against CCP governance in East Turkistan, most notably through the various documents published by or addressed to the United Nations. This includes a document detailing the international standards broken in the region, written by a collaboration of United Nations experts.61https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Terrorism/SR/OL_CHN_18_2019.pdf It is fair to interpret both China’s disobedience of international rulings and its human rights abuses as a disregard for international law.62Richard Javad Heydarian, “Can China Really Ignore International Law?,” National Interest, August 1, 2016, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/can-china-really-ignore-international-law-17211 Dan Zhu contends China’s ambivalence toward legal structures of international governance stem from its history—China has been reticent in its participation in international governance because of its reservations, but China also has huge ambitions within these structures.63Dan Zhu, China and the International Criminal Court, (Singapore: Palgrave, 2018), 3. Their caution towards global governance is rooted in their history, and is not indicative of apathy, which means the international community can elicit change through international pressure and governance structures.

China has attempted to hide gross human rights abuses, intentionally continuing repressive treatment within East Turkistan, but their responses to international media show a preoccupation with their own reputation. They are paying attention to social media campaigns, as well as international news media and statements from governing bodies. China may take a long time to respond, but this may be a deliberate choice, and their responses are always “public-facing,” whether they are official statements, Chinese state media, or even performative promotions of Uyghur culture. Governmental and media pressures do elicit CCP responses, and the international community should remember this.

Legal Reactions to Chinese State Media

In July 2020, CGTN was found in serious breach of several UK broadcasting regulations, and UK media watchdog OFCOM has faced increasing pressure to ban the network.64Michael Savage, “China’s TV channel faces UK ban as complaints mount,” The Guardian, July 26, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/media/2020/jul/26/chinas-tv-channel-faces-uk-ban-as-complaints-mount One particularly complex complaint is about the forced confession of Peter Humphrey, who claims he was drugged, locked in a chair, and held captive inside a metal cage; his interviewers claim they did not think he was “in distress or under duress.”65Patricia Nilsson, “China’s CGTN found in serious breach of UK broadcasting rules,” Financial Times, July 6, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/ee7366fd-6f8f-4901-b22f-a1617774d288 The United States is following a similar tactic as they tighten rules on Chinese and other foreign-run state media, labelling various outlets as “foreign missions.”66AFP, “US tightens rules on Chinese state media over ‘propaganda’ concerns,” The Guardian, February 18, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/feb/18/us-chinese-media-propaganda-state-department De-platforming some of these outlets may discourage the dissemination and production of blatant and cruel proof-of-life videos.

Major social media corporations have begun to clearly label state media affiliations. YouTube provides an information panel providing publisher context underneath videos published by Chinese state media’s official accounts.67“Information panel providing publisher context,” Youtube Help, October 17, 2020, https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/7630512?hl=en This information panel is included when “a channel is owned by a news publisher that is funded by a government, or publicly funded.” Twitter also includes the tagline “China state-affiliated media” on CGTN’s activity, as they do with representatives, officials, or affiliates to the permanent Security Council governments.68“About government and state-affiliated media account labels on Twitter,” Twitter, October 13, 2020, https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/state-affiliated-china Twitter goes further to say that they “will not recommend or amplify accounts or their Tweets with these labels to people.”69https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/state-affiliated Facebook and Instagram are among social media platforms that do not inform their users of account affiliations.

Live Police Database

The viral campaigns launched by Uyghur activists, most notably #StillNoInfo and #ShowThemAll, reveal the lacking information surrounding these cases is what provokes the strongest emotion. The ambiguity surrounding the facts may halt action taken by international concern, but if anything, this confusion only exacerbates that concern. In response to the proof-of-life video featuring her two granddaughters, Rebiya Kadeer demanded information about all 35 of her missing relatives, none of whom she has been able to reach.70Rebiya Kadeer (@KadeerRebiya), “To Global Times Of Chinese Communist Party: Why can’t you show all of my relatives that I am looking for? I have been seeking information about 35 members of my family. Chinese propaganda machine Global Times has shown only three of them to discredit me @globaltimesnews,” Twitter, January 11, 2020, https://twitter.com/KadeerRebiya/status/1215843218090287104

The CCP should allow access to records of Uyghurs’ imprisonments, detentions, re-education visits, home-arrests, labor placements, and any other punitive measures. Almost all countries keep electronic records of judicial and punitive measures. If China does not follow the same practice, then doing so will allow not only international audiences to understand the Uyghur situation better but also China to get a better grasp on its own statistics.

Leaked databases of detainee records such as the Qaraqash Document suggest that the CCP gathers and stores extensive information about the alleged million-plus Turkic and/or Muslim peoples it has disappeared into various forms of state detention.

In Sweden, the largest criminal records collection in the world became available to the public as of January 2014, allowing anyone to search the criminal history of their friends and neighbors, even providing a map function.71“Demand for law change after Lexbase launch,” Sveriges Radio, January 28, 2014, http://sverigesradio.se/sida/artikel.aspx?programid=2054&artikel=5768451 This website has been heavily criticized for alienating past offenders and violating rights to privacy. However, in many countries, criminal records are centralized. The Center for the Protection for National Infrastructure released a comparative report on the availability of criminal record information in 2014, which is information that all states hold.72“How to obtain an Overseas Criminal Record Check,” Center for the Protection of National Infrastructure, April 2014,

https://web.archive.org/web/20140808122256/http://www.cpni.gov.uk/documents/publications/2014/2014-04-28-overseas-criminal-records-quick-reference.pdf?epslanguage=en-gb Portugal’s criminal record system is an electronic database maintained by their General Direction for the Administration of Justice. In Canada, criminal records are stored in a database called the Criminal Records Information Management Services.73“Homepage,” Canadian Police Information Centre, October 13, 2020, https://www.cpic-cipc.ca/index-eng.htm In the United States, local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies compile criminal records that are uploaded onto a variety of databases of which the National Crime Information Center is the central access point.[5]

One might assume that state media would have access to information gathered and held by the state. However, proof-of-life videos are often framed in ways that appear this is not the case. It seems unlikely that there is no record of the missing. Leaked databases of detainee records such as the Qaraqash Document suggest that the CCP gathers and stores extensive information about the alleged million-plus Turkic and/or Muslim peoples it has disappeared into various forms of state detention.

Since mid-2020, a growing body of international experts have begun to label China’s repression in East Turkistan as crimes against humanity and genocide. On January 19, 2021, the United States declared that China committed genocide against Uyghurs.74“US: China ‘committed genocide against Uighurs’,” BBC News, January 21, 2021, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-55723522 Access to CCP policing and security records for United Nations experts and representatives from human rights organizations would be crucial in determining the status of missing people. State investigations into its own wrongdoings in a mere 22 cases does not begin to scratch the surface: with mounting frustration from expatriates who still have no information, more proof is needed.

VIII. Conclusion