A Uyghur Human Rights Project report by Peter Irwin. Read our press statement on the report; download the full report in English, 简体中文, Bahasa Indonesia, عربى, and Türkçe; and find a printable, one-page summary of the report.

Find exclusive coverage of the report in the BBC, and additional coverage in The Associated Press, ABC, The Independent, Foreign Policy, ChinaFile, The China Project, PRI The World, Radio Free Asia, The New Arab, Cultural Property News, Radio New Zealand, DAWN, Daily Islamabad Post, Al-Mashriq, Catholic News Agency, Islam21c, UCA News, Religion News.

Key Takeaways

- The Chinese government has pursued an extreme campaign to prohibit or marginalize Islamic practices foundational to Uyghurs;

- UHRP compiled a dataset of 1,046 cases of Turkic imams and other religious figures from East Turkistan detained or imprisoned for their association with religious teaching and community leadership since 2014;

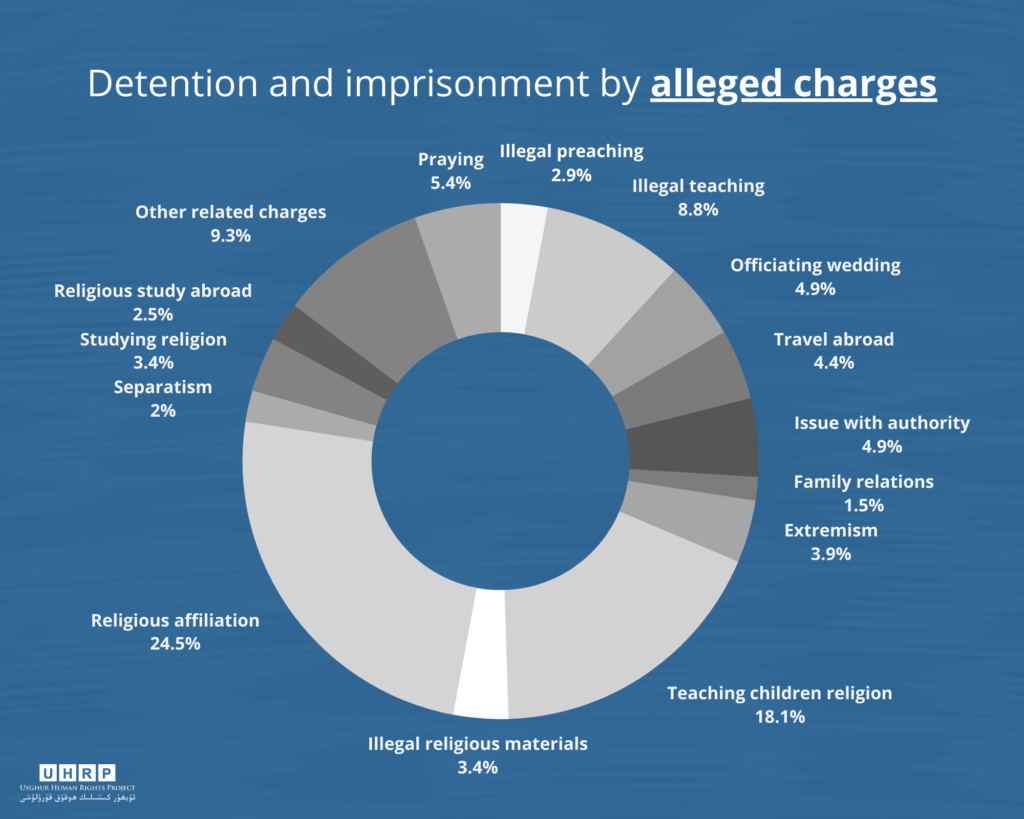

- Alleged “charges” include quotidian religious practices and expression like basic religious teaching to children, prayer outside state-approved mosques, possession of “illegal” religious materials, communication or travel abroad, separatism or extremism, and officiating or preaching at weddings and funerals;

- Over 40% of cases in the dataset include prison sentences, and of the 304 cases we reviewed that included data on the length of sentence, 96% included sentences of at least five years, and 25% included sentences of 20 years or more, including 14 life sentences, often on unclear charges;

- Interviews with Uyghur imams outside China reveal harassment and persecution spanning several decades, who describe varying degrees of persecution beginning in the 1980s until they fled the region in 2015 and 2016 as a result of surveillance and the threat of detention;

- The Chinese government is targeting influential and knowledgeable Uyghur and other Turkic religious figures, along with Uyghur intellectuals, in an attempt to halt the intergenerational transmission of religious knowledge in East Turkistan.

I. Executive Summary

Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples in East Turkistan (also known as the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China) have long endured repressive Chinese government policies targeting their cultural identity. Religious leaders in particular have been frequent subjects of state-directed abuse.

This report presents new evidence detailing the extent to which Uyghur religious figures have been targeted over time. Using primary and secondary sources, we have compiled a dataset consisting of 1,046 cases of Turkic imams and other religious figures from East Turkistan detained for their association with religious teaching and community leadership since 2014.1An additional 30 cases from 1999-2013 have also been included. The total cases in the dataset should not, however, be construed as an estimate of the total number imams detained or imprisoned. The total cases we have reviewed likely represent only the very tip of the iceberg, given severe restrictions on access to information.

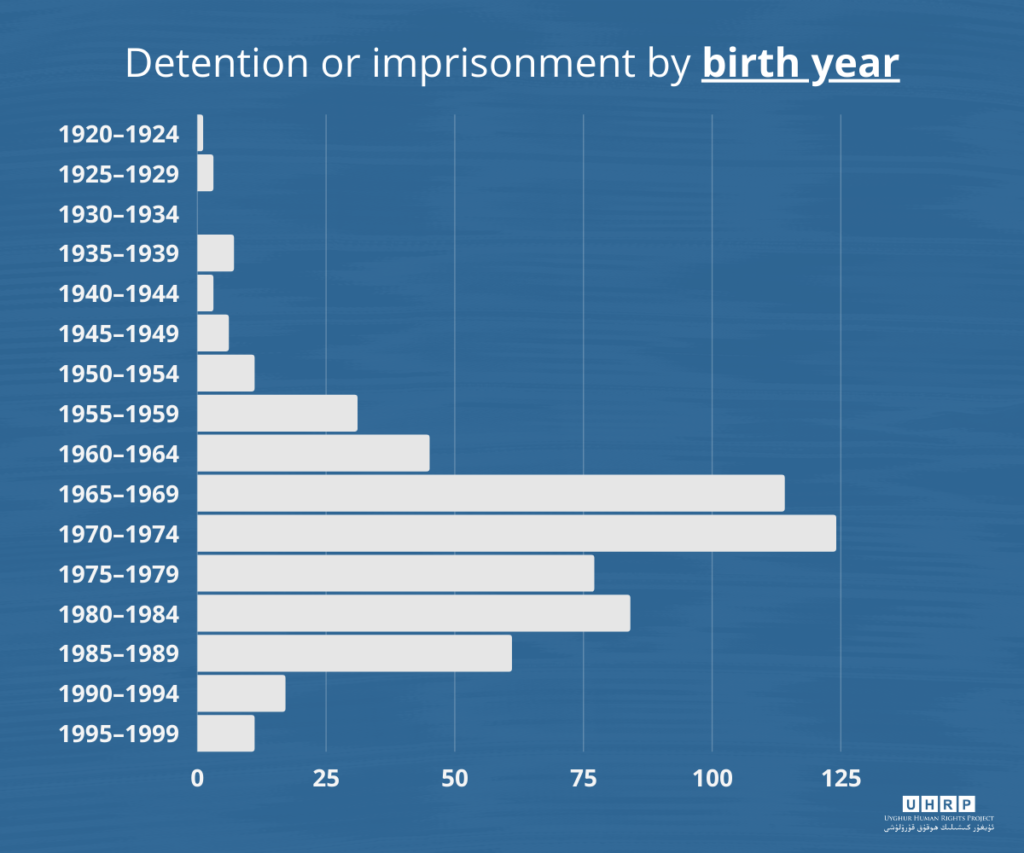

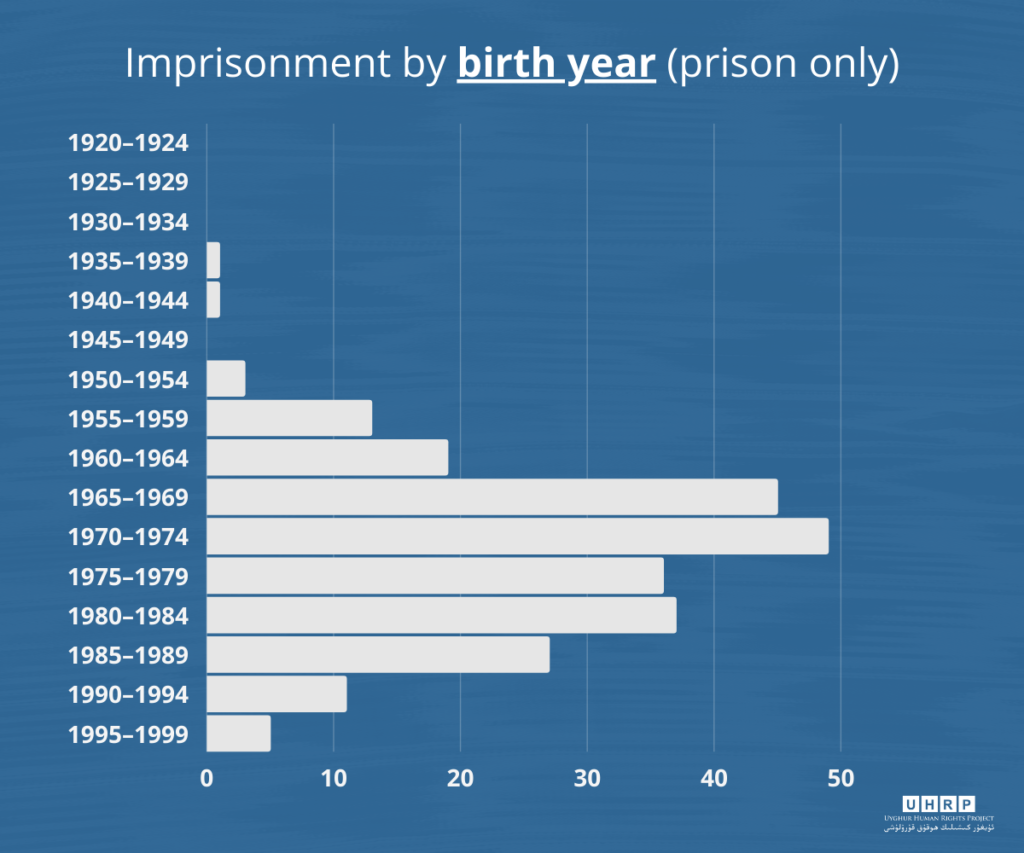

The dataset shows that the government has targeted mostly male Uyghur religious figures born between 1960 and 1980. However, a sizable minority of Kazakh Islamic clergy of roughly the same demographic group have also been detained, as well as several Kyrgyz, Uzbek, and Tatar figures, indicating the breadth of persecution. Up to 57 cases in our dataset (5%) concern individuals over the age of 60.

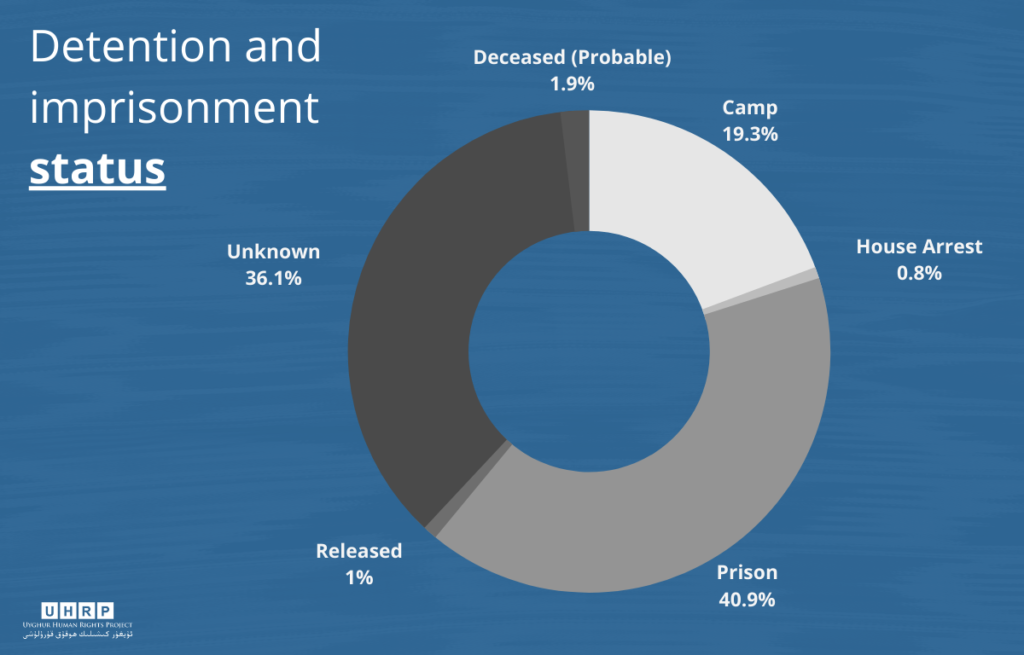

The high rate of prison sentences (versus shorter-term camp detentions) in the dataset offers clues about the target and motivation of Chinese government policy in relation to religious figures. That 41% of the individuals in our dataset have been given prison sentences illustrates the intention of the Chinese government not just to criminalize religious expression or practice, but also to consider imams criminals by virtue of their profession. Many of the cases indicate that government definitions of “illegal” or “extremist” have been ambiguous for years, likely purposely so. As a result, Turkic clergy in East Turkistan have been sentenced to prison terms for quotidian religious practices and expression protected under both Chinese and internationally recognized human rights treaties.

Grounds for imprisonment in the cases we reviewed include “illegal” religious teaching (often to children), prayer outside a state-approved mosque, the possession of “illegal” religious materials, communication or travel abroad, separatism or extremism,2Both “separatism” and “extremism” are defined very broadly by the Chinese government and have been used to justify the detention of Uyghurs on dubious grounds. and officiating or preaching at weddings and funerals, as well as other charges that simply target religious affiliation. The dataset includes cases of prison sentences of 15 years or more for “teaching others to pray,” “studying for six months in Egypt,” and “refusing to hand in [a] Quran book to be burned,” as well as a life sentence for “spreading the faith and for organizing people.”

Some of those detained were once formally sanctioned by the government to serve as imams, suggesting that the imams’ “criminality” is the result of a policy reversal. Several cases also indicate that the government applied retroactive sentences for alleged violations that took place years prior.

Our dataset also indicates a major spike in the sentencing of religious figures in 2017, tracking closely with available government data.3Chris Buckley, “China’s Prisons Swell After Deluge of Arrests Engulfs Muslims,” New York Times, August 31, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/31/world/asia/xinjiang-china-uighurs-prisons.html Of the 304 cases we reviewed that included data on length of sentence, 96% included sentences of at least five years, and 25% included sentences of 20 years or more, including 14 life sentences, often on unclear charges.

In addition to compiling and collating detention data, we also interviewed Uyghur imams outside of East Turkistan, as well as the son of an imam currently in detention. Our interviewees revealed details of harassment and persecution spanning several decades for their role serving their local congregations. The imams described facing varying degrees of persecution beginning in the 1980s until they fled the region in the 2015 and 2016 as a result of surveillance and the threat of detention. Their stories fill in many of the gaps in our understanding of the on-the-ground effects of Chinese government policies over time, as well as of forms of everyday resistance on the local level.

In the 1990s and 2000s, Chinese authorities in East Turkistan passed a proliferation of laws and regulations governing religion from the national to the local level, buttressing the new regulations with obligatory loyalty pledges, state-managed trainings, examinations, and enhanced oversight of imams in order to keep religious teaching under strict control. Uyghur-led protests in the 1990s, which resulted from restrictions on cultural practice, prompted the regional government to harden its policies even further, which led to a perpetuating cycle of domination and control well into the 2000s.

Imams we interviewed report having been persistently watched, followed, scrutinized, and directed in their work in the mosque, which escalated to a point where they felt that they no longer played a positive role in their work. All of our interviewees decided to flee East Turkistan because of relentless government policies and fears of possible detention. In 2017, the explosive growth in camps designed to arbitrarily detain and forcibly indoctrinate Uyghurs en masse confirmed those fears.

This report makes clear that imams and other religious figures, similar to members of the intellectual class in Uyghur society, stand at the very center of what one might describe as concentric circles of repression. The government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has targeted religious leaders for decades. So, too, did pre-PRC leaders, given their discomfort with groups and identities that might compete with the influence of the central authorities. Whereas all Turkic peoples in East Turkistan have faced strict government controls in recent years, and whereas increasingly capricious government authorities are now willing to detain just about anyone, religious figures were targeted early and severely.

Chinese government efforts to detain and sentence Uyghur clergy have also taken place within the context of a state-led campaign to substantially modify or completely destroy religious and cultural sites like mosques, shrines, and cemeteries. Researchers have found that since around 2017, up to 16,000 mosques in East Turkistan (roughly 65% of all mosques) have been destroyed or damaged as a result of government policies with an estimated 8,500 demolished outright.4Australian Strategic Policy Institute, “Cultural erasure: Tracing the destruction of Uyghur and Islamic spaces in Xinjiang,” September 24, 2020, https://www.aspi.org.au/report/cultural-erasure. For an earlier report on the destruction of religious heritage, see Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Demolishing Faith: The Destruction and Desecration of Uyghur Mosques and Shrines,” October 2019, https://uhrp.org/press-release/demolishing-faith-destruction-and-desecration-uyghur-mosques-and-shrines.html At the same time, around 30% of all important Islamic sacred sites such as shrines, cemeteries, and pilgrimage routes have been demolished and another 28% damaged or altered, mostly since 2017.

As a result, even if imams have not been detained or forced out of their mosques, the physical destruction of their places of worship means that they have no place to preach or pray, given that religious practice at home has been prohibited. In the 1990s and 2000s, the Chinese government began confining religious practices only to mosques according to the law, only to later begin destroying the very mosques that served as the only “legal” spaces for religious practice.

In addition to placing harsh restrictions on imams and religious figures, and to destroying the physical spaces where they operate, the Chinese government has pursued an extreme campaign to prohibit nearly every Islamic practice foundational to the Uyghur people. In policy and practice, authorities have prohibited the teaching of religion at all levels of education; banned the use of traditional Islamic names like Muhammad and Medina for Uyghur children;5Javier Hernández, “China Bans ‘Muhammad’ and ‘Jihad’ as Baby Names in Heavily Muslim Region,” New York Times, April 25, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/25/world/asia/china-xinjiang-ban-muslim-names-muhammad-jihad.html banned long beards for Uyghur men and headscarves for Uyghur women;6Article 9(8), 新疆维吾尔自治区去极端化条例 [XUAR Regulations on De-Extremification], passed March 29, 2017, effective April 1, 2017, www.xjpcsc.gov.cn/article/225/lfgz.html instituted an “anti-halal” campaign to prevent the labeling of food and other products as halal;7Lily Kuo, “Chinese authorities launch ‘anti-halal’ crackdown in Xinjiang,” The Guardian, October 10, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/oct/10/chinese-authorities-launch-anti-halal-crackdown-in-xinjiang criminalized Hajj pilgrimage without government approval;8中华人民共和国国务院令 [Religious Affairs Regulations], Article 70, amended June 14, 2017, effective February 1, 2018, http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2017-09/07/content_5223282.htm and adopted legislation broadly defining quotidian religious practices as “extremist,” which a group of UN independent experts urged to be repealed in its entirety.9UN Special Procedures Joint Other Letter to China, OL CHN 21/2018, November 12, 2018, spcommreports.ohchr.org/TMResultsBase/DownLoadPublicCommunicationFile?gId=24182

Representatives of the state also began purposefully humiliating imams and religious figures in recent years, including by forcing them to dance in public or participate in degrading activities like singing songs praising the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).10Express Tribune, “Suppressing religious freedoms: Chinese imams forced to dance in Xinjiang region,” April 18, 2015, www.tribune.com.pk/story/871879/suppressing-religious-freedoms-chinese-imams-forced-to-dance-in-xinjiang-region/. See also Sounding Islam in China, “Imams dancing to ‘Little Apple’ in Uch Turpan, Xinjiang,” March 25, 2015, soundislamchina.org/?p=1053 One imam interviewed by UHRP for this report corroborated this in his testimony, and shared that he and several hundred other imams were forced to wear athletic clothing and dance in a public square in 2014.

This evidence has been compiled by journalists, researchers, and experts, illustrating how Chinese government policy has been designed to eliminate core aspects of Islamic practice and expression. Chinese authorities have gone to great lengths, however, to ensure that some Islamic practice remains in East Turkistan as a means of demonstrating the government’s purported commitment to respecting “normal religious activities.”11Article 36 of the PRC Constitution states “The state protects normal religious activities,” which is repeated in the Regulations on Religious Affairs and other official documents. The use of the qualifier “normal” has allowed the government to narrowly define what constitutes legal religious activity, and criminalize a long list of behavior protected under international law. The government boasts, for example, that it has strengthened the “cultivation and training of clerical personnel”12Xinhua, “Fact Check: Lies on Xinjiang-related issues versus the truth,” February 5, 2021, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2021-02/05/c_139723816.htm by operating training institutes, but these schools have served, for many years, to maintain strict control over the imams and their teaching.13See Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Sacred Right Defiled: China’s iron fisted repression of Uyghur religious freedom,” April 30, 2013, pp. 29–35, https://docs.uhrp.org/Sacred-Right-Defiled-Chinas-Iron-Fisted-Repression-of-Uyghur-Religious-Freedom.pdf Any expression of religious identity by Uyghurs in Chinese state media appears highly choreographed, repeating Party slogans and policies, and belies evidence presented in this report and elsewhere. What remains of religious practice among Uyghurs persists as merely a shell of its former self—thoroughly dispossessed of the richness of Islam freely practiced elsewhere.

The Chinese government has targeted influential and knowledgeable Uyghur and other Turkic religious figures in a transparent attempt to halt the intergenerational transmission of religious knowledge in East Turkistan. By reducing legal religious practice to only individuals over the age of 18 within the confines of state-sanctioned mosques led by state-sanctioned imams while firmly prohibiting teaching religion to children at home, while then later demolishing even some of those state-sanctioned religious structures, the Chinese government is extinguishing free religious practice in a single generation. Taken together, these policies will make it difficult—if not impossible—for Uyghurs to maintain any semblance of religious expression in the years to come.

The current campaign targeting Uyghur and Turkic people bears a striking resemblance to the horrors of the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) as it was experienced in East Turkistan.14James Millward, writing in relation to the situation in East Turkistan during the Cultural Revolution, describes reports of “Qur’ans burnt; mosques, mazars, madrasas and Muslim cemeteries shut down and desecrated; non-Han intellectual and religious elders humiliated in parades and struggle meetings; native dress prohibited; long hair on young women cut off in the street,” which directly resemble forms of repression taking place in East Turkistan today. See James Millward, Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), p. 275. While policies and forms of repression in the two eras do indeed share some similarities, the scale and scope of what is happening today makes this current campaign of repression distinct, particularly thanks to the ability of the state to utilize sophisticated technologies to “predict” criminality and infiltrate even the most intimate unit of the family home. The Turkic population of East Turkistan is facing its darkest era in decades, and Uyghur religious figures have borne the brunt of repression.

* * *

The Chinese government’s broad campaign to eliminate central aspects of the Uyghur identity, including religious belief and practice, likely amounts to genocide under international law.15At the time of publishing, several governments have called the treatment of Uyghurs a genocide, including the United States, Canada, and the Netherlands. Additional studies have come to the same conclusion. See Newlines Institute, “The Uyghur Genocide: An Examination of China’s Breaches of the 1948 Genocide Convention,” March 8, 2021, https://newlinesinstitute.org/uyghurs/the-uyghur-genocide-an-examination-of-chinas-breaches-of-the-1948-genocide-convention/; and BBC, “Uighurs: ‘Credible case’ China carrying out genocide,” February 8, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-55973215 Rather than respond to calls to close the concentration camps and respect Uyghur rights over the last three years, Chinese leaders have doubled down and claimed that their approach has been “completely correct.”16Isaac Yee and Griffiths, James, “China’s President Xi says Xinjiang policies ‘completely correct’ amid growing international criticism,” CNN, September 27, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/09/27/asia/china-xi-jinping-xinjiang-intl-hnk/index.html Despite mounting criticism, Chinese authorities have indicated that they will forge ahead in this campaign, evidenced by the continued construction of camps,17Megha Rajagopalan, Alison Killing, and Christo Buschek, “China Secretly Built A Vast New Infrastructure To Imprison Muslims,” Buzzfeed News, August 27, 2020, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/meghara/china-new-internment-camps-xinjiang-uighurs-muslims and the increasing use of widespread forced labor.18Amy Lehr and Efthimia Maria Bechrakis, “Connecting the Dots in Xinjiang: Forced Labor, Forced Assimilation, and Western Supply Chains,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, October 16, 2019, https://www.csis.org/analysis/connecting-dots-xinjiang-forced-labor-forced-assimilation-and-western-supply-chains

Although the international community has taken some small steps to respond to the repression, criticism has been mostly mild, if not entirely muted. Governments have an obligation to call out these abuses loudly and often. The Chinese government has been responsive, albeit defensively, to public statements of concern and condemnation, but like-minded governments who understand the implications of tacitly allowing this kind of behavior must cooperate in calling out the abuse. Without a robust response, the Uyghur identity itself—in which religion plays a significant role—will be under an ever graver threat.

II. Sources and Methodology

The scope of this report was constrained by some difficulties accessing information from East Turkistan—an environment less accessible to researchers, reporters, and advocates than most others in the world today.

However, we have pieced together a collection of stories from Uyghur imams and religious leaders who lived in East Turkistan from the 1960s until roughly 2016, and who experienced the trajectory of the Chinese government’s repression of religious figures first-hand. As such, the report situates Uyghur religious leaders within the context of the Chinese government’s relationship with Islam. We have chosen to focus our analysis on these imams because of what their fate tells us about the motivation and objective of Chinese leaders since the most recent period of forced assimilation, which began around 2014.

The report offers one more piece of a larger puzzle that researchers, activists, journalists, and governments have been attempting to piece together—particularly since 2016, when information was already hard to come by.

This is not a report about Uyghur religious freedom, per se. It does not attempt to comprehensively trace Chinese government restrictions on religious practice over many decades, nor does it offer an expansive study of the role of Islam in Uyghur life, though these themes run throughout. The report views these restrictions through the lens of Uyghur imams and other prominent religious figures over time. Furthermore, it attempts to illustrate the assault on prominent religious figures in particular, what this assault looks like in its implementation, and the results for Uyghurs and others on the ground.

The report offers one more piece of a larger puzzle that researchers, activists, journalists, and governments have been attempting to piece together—particularly since 2016, when information was already hard to come by. The complete puzzle may never be fully assembled, but our collective work contributes to a clearer picture of life for Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims in East Turkistan today.

We conducted a total of five telephone interviews for this report from August to November 2020. Four of our interviewees are former imams from East Turkistan; one is the family member of a detained imam. All interviewees worked in either official or unofficial capacities at local mosques across East Turkistan and are now residing abroad. We have used pseudonyms to conceal their identities at their request, as all expressed fear of retaliation for speaking publicly.

To compile the dataset of cases of detention and imprisonment, we used data from four sources: (1) the Uyghur Transitional Justice Database (UTJD);19Uyghur Transitional Justice Database: www.utjd.org (2) the Xinjiang Victims Database (Shahit.biz);20Xinjiang Victims Database: https://www.shahit.biz/eng (3) data compiled in the diaspora by Uyghur scholar and researcher Abduweli Ayup;21Uyghur scholar and researcher Abduweli Ayup has been able to track down an extensive list of detained imams through various public and private sources beginning in 2018. These sources include direct contacts, leaked documents such as the “Qaraqash List” and the “Aksu List,” and documents sourced from Chinese government websites. His organization, Uyghur Yardem, based in Norway, conducted interviews with Uyghurs in Istanbul between December 2019 and May 2020, and compiled a list of 4577 cases of detention and imprisonment.These sources include the Congressional Executive Commission on China’s political prisoner database, reports from journalists, and other sources. and (4) information gleaned from additional open-source materials online.22These sources include the Congressional Executive Commission on China’s political prisoner database, reports from journalists, and other sources. We provide additional information regarding the compilation of cases and our methods at the end of Section III.

Notes on terminology

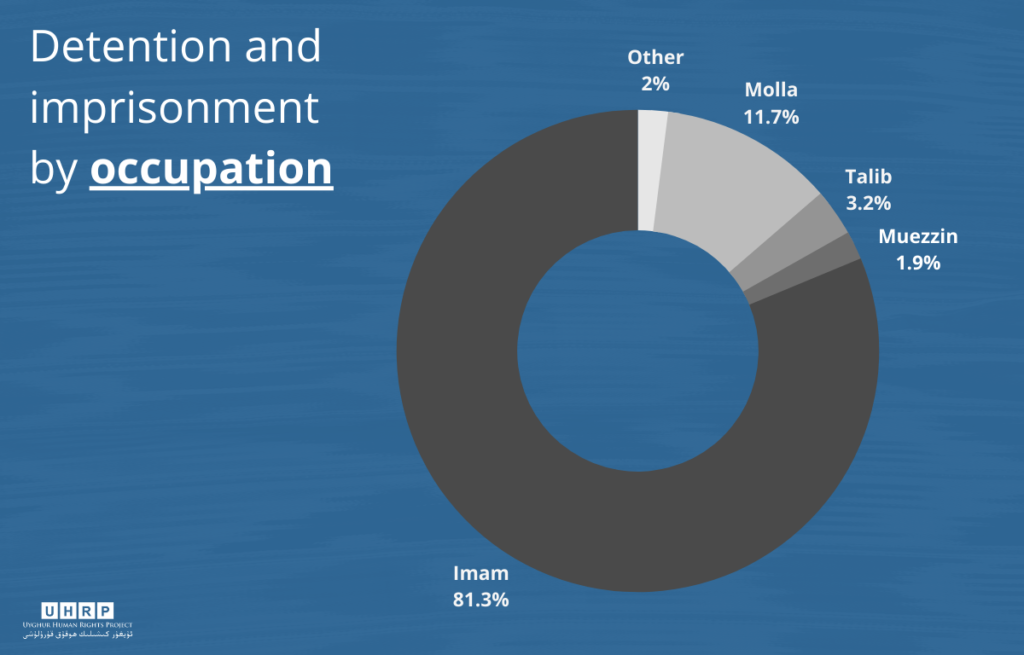

In Islam, an imam is the worship leader of a mosque, but may also perform other duties in the local community. The report takes a relatively broad definition of “imam” as a religious figure in Uyghur society to include those officially sanctioned by the Party-state; those who self-identify as an imam, but do not hold an official designation with the government; and those who engage in teaching (or leading prayer) outside the family home.

In addition to imams, we have also included khatibs, talibs, and mollas in our dataset. A “khatib” is an imam who typically leads Friday or Eid prayer, whereas “talib” refers to religious students. We have chosen to include talibs in our dataset given that these figures are often studying to become imams, though they make up a small proportion of those detained. A “molla” is a more flexible category in our dataset, as there are no clear-cut qualifications for someone to be called by that name in the Uyghur community. As scholar Elke Spiessens points out, “In a basic sense, a Uyghur molla is a Muslim intellectual, someone who has specialized knowledge about Islam and is thereby bestowed a certain level of authority.”23Spiessens, “Diasporic Lives of Uyghur Mollas,” p. 279. Some individuals in the dataset were listed by compilers as “damollas,” advanced Islamic scholars with the authority to train other scholars who were “often much sought after by students from all over Xinjiang.”24Ibid. Some interviewees also used the term sheikh, which refers in some cases to knowledgeable Uyghur religious scholars or in some cases to leaders of Sufi groups or custodians of shrines. Throughout the report, we use the phrasings religious leaders, religious figures, and clergy interchangeably to represent these broad categories.

Uyghur woman also take up leading roles in religious affairs and teaching as büwi who “serve as mourners at funerals” as well as conducting home-based rituals for healing and reciting the Qur’an at religious gatherings.25Harris, Rachel and Yasin Muhpul. “Music of the Uyghurs.” In The Turks, Vol.6. (Istanbul: Yeni Turkiye Publications, 2002), pp. 542–49. Büwi—also called qushnach in some areas—lead women’s religious gatherings including mourning rituals and regular khetme gatherings, which include forms of zikr and Qur’anic readings. Büwis often provide a basic religious education for local children. Although our dataset does not explicitly include cases of Uyghur büwiwho have been detained, it is very likely that they have been targeted for persecution as well, given the detention of religious figures generally. Our dataset includes 23 women, some of whom may have acted in this capacity.

This report focuses on how policies have targeted Uyghur religious figures in East Turkistan in particular, while also recognizing that the same policies apply to other Turkic and/or Muslim peoples in the region. When we refer to Turkic peoples in this report, we are referring not only to Uyghurs, but also to Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, and Tatars (though the latter two make up a much smaller percentage of the regional population). Kazakhs, for example, make up 18% of the detained population in our dataset, though their population only comprises roughly 7% of the total population and 12% of the Turkic population of the region.26The high proportion of Kazakh imams in the dataset is likely a result of the work of the Atajurt Kazakh Human Rights Organization, a documentation organization based in Almaty which has conducted extensive interviews with Kazakhs connected to East Turkistan. The cases from Atajurt are reflected in the higher numbers of Kazakhs in the Shahit.biz database—one primary source for the dataset presented in this report.

We use the terms “detained” or “in detention” to refer to those people who have been forcibly sent to camps. The Chinese government refers to these facilities as “re-education” or “vocational training” centers despite evidence illustrating their coercive nature. Not all facilities in this network are identical—evidence shows the varying degree to which Uyghurs and others are detained, the treatment they receive, the ability of internees to leave the facilities, and the length at which they are held.27For detailed information about the nature of the arbitrary detention system in East Turkistan, see Uyghur Human Rights Project, “The Mass Internment of Uyghurs: ‘We want to be respected as humans. Is it too much to ask?’” August 23, 2018, https://uhrp.org/report/mass-internment-uyghurs-we-want-be-respected-humans-it-too-much-ask-html/ One constant, however, is that strict coercion plays a fundamental role in this type of detention. We make a distinction between detained religious figures and those who have been arrested and sentenced to prison terms, using the term “imprisoned” to refer to the latter cases.

Who should read this report?

This report should be essential reading for policy-makers interested in pushing back against China’s clear abrogation of fundamental human rights for Uyghurs; members of the academic community, who are increasingly shut out of the region to conduct research; the Uyghur community abroad, who continue to watch with horror as communication with family members and friends plunges further into darkness; Muslims—and members of all religious groups—around the world who recognize the importance that faith can play in maintaining bonds and living moral lives; and the general public, who are concerned about the systematic targeting of people for their faith, and for the assault on religious leaders who represent community cohesion and shared identity.

III. Dataset on Detention of Religious Figures

Key findings

Following exhaustive research compiling cases from multiple databases,28See “Notes on compilation of data” on page 28 for information on data sources. we recorded a total of 1,046 Turkic religious figures who may have been detained in camps or prisons in East Turkistan primarily since 2014.29An additional 30 cases from 1999 to 2013 have also been included in the total 1,046, though the vast majority of individuals whose records we researched (571 of 601) were detained in or after 2014. A small number of these individuals have been released, are now under house arrest, or have died in detention. The dataset includes 850 imams, 122 mollas, 20 muezzins (those who perform the call to prayer), 33 talibs, and several others identified with different occupations, possibly because they gave up earlier duties as imams.

Of those people, 428 have been imprisoned, while 304 of those include information on the length of sentences currently being served (discussed in more detail below). Another 202 religious figures have been detained in camps,30Chris Buckley, “China’s Prisons Swell After Deluge of Arrests Engulfs Muslims.” 18 have been released (including 8 now under house arrest),31Several Uyghur imams UHRP spoke to in the fall of 2020 told us that they or their families were living under conditions which effectively meant that they lived under “house arrest.” Although only eight cases explicitly mention house arrest, it may be fair to say that all 18 were living under the same conditions. and 18 have died in either a prison or a camp, or shortly following their release.32Two of those who reportedly died in a prison or camp were in their 80s and one in his 90s at the time of their deaths. An additional 378 cases we reviewed lack data on current status.

Detentions and imprisonments over time

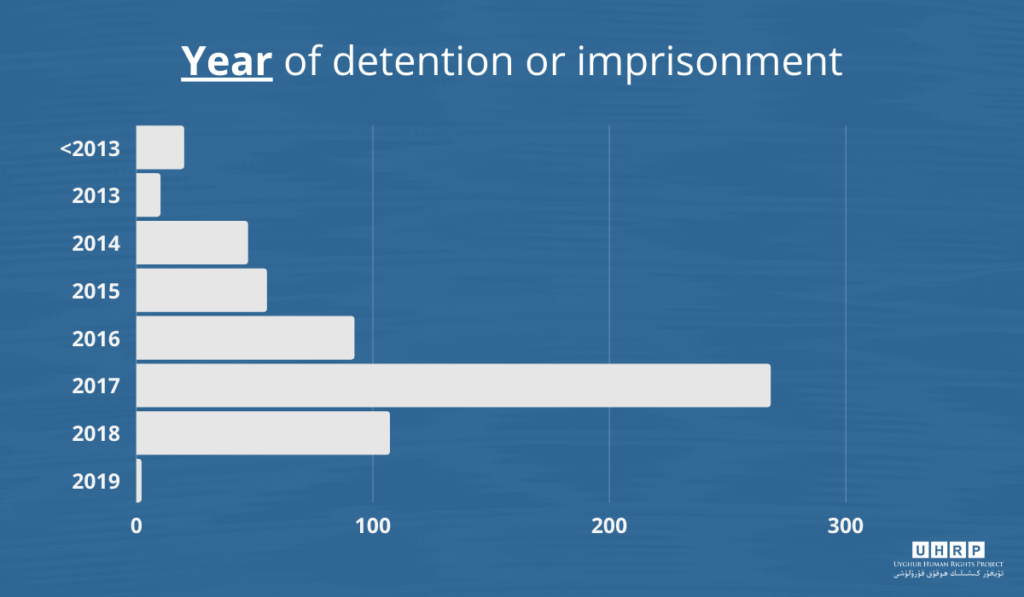

Of the detentions we reviewed, 45% (of the 601 that included this information) occurred in 2017. Another 15% and 18% of detentions took place in 2016 and 2018, respectively. Nearly 19% of detentions took place between 2013 and 2015, ahead of more widespread incarceration beginning in 2016.

Data on prison sentences offers a similar picture of a build-up of detentions starting in 2014 and peaking in 2017, which tracks fairly consistently with government data reported by the New York Times in 2019.33Chris Buckley, “China’s Prisons Swell After Deluge of Arrests Engulfs Muslims.” Our data shows a drop in prison sentences for religious figures from 2017 to 2018 when compared to government data. This may be partially explained by the government’s targeting of religious figures for imprisonment earlier than the general population.34See Asim Kashgarian, “Victims’ Families Say Uighur Religious Leaders Main Target in China,” Voice of America, June 10, 2020, https://www.voanews.com/extremism-watch/victims-families-say-uighur-religious-leaders-main-target-china Another factor may be a lack of data, considering that lines of communication from East Turkistan to the rest of the world began to close around this time.

Detentions and imprisonments by prefecture and other administrative divisions

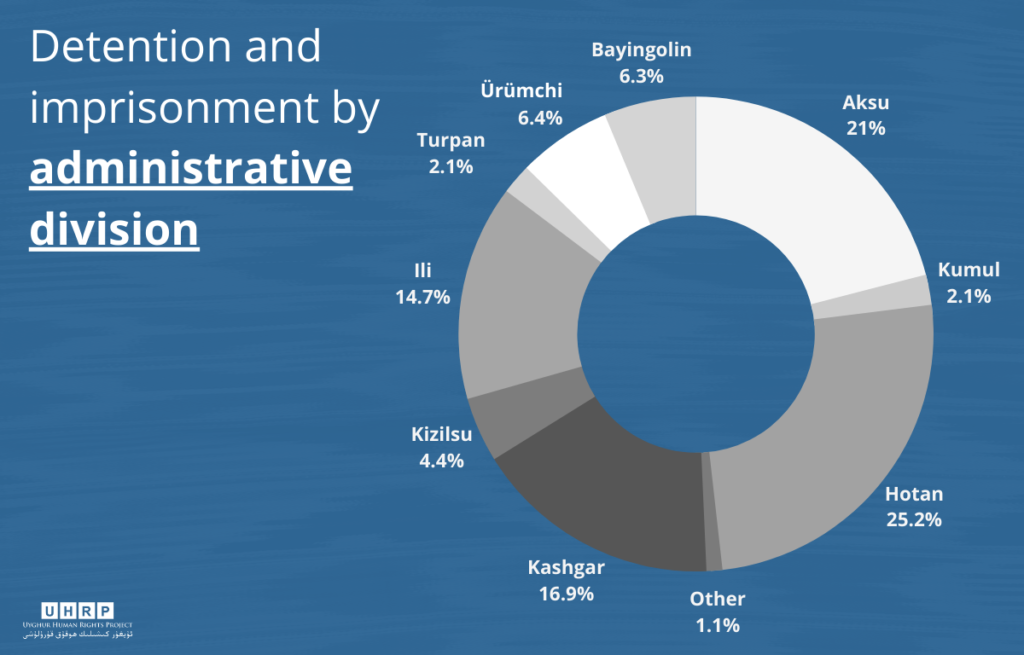

Detentions occurred at the highest rates in southern areas with high Turkic populations where the regional government has focused its repressive policies: Hotan (25%), Aksu (21%), and Kashgar (17%). Ili prefecture, in the northern part of the region, accounts for a further 15% of the cases we reviewed. Lower levels of detention in all other prefectures indicate that the detention policy remains widespread. Of those detained, the vast majority are Uyghur (843 cases, 81%), but also included Kazakh (187 cases, 18%), Kyrgyz (12 cases, 1%), a single Uzbek case (0.1%), and a single Tatar case (0.1%). Despite making up only 12% of the Turkic population in the region, Kazakhs make up a comparably larger proportion of the dataset, given that imams make up a large percentage of the Kazakhs who have been detained.35One other reason for the disproportionate number of Kazakhs represented is the considerable number of cases entered into the Shahit.biz database, which compiled a large number of cases from Kazakhstan from family members of detained individuals. There is also evidence that non-Turkic peoples, including Hui, have been detained. See also Gene Bunin, “Xinjiang’s Hui Muslims Were Swept Into Camps Alongside Uighurs,” Foreign Policy, February 10, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/02/10/internment-detention-xinjiang-hui-muslims-swept-into-camps-alongside-uighur/

Detentions and imprisonments by sex

Though the targeted individuals in our dataset are overwhelmingly male (98%), the records also include information on 23 women (2%) detained in camps and imprisoned, some for “teaching Islam to children.” Many of the women are labelled as mollas or imams (both male-gendered terms), but it is more likely that they would be considered büwi by their communities. Büwitake up leading roles in religious affairs and teaching, but may not have been classified by the government or regarded by the submitter of cases as official religious practitioners. It is possible that they are underrepresented in our data.

Detentions and imprisonments by age

Detained religious figures in our dataset were primarily born between 1965 and 1975 (44% of cases which include this data). Large numbers of clergy born in the 1950s and 1980s were also detained, however. Stunningly, authorities have also rounded up elderly Uyghurs as well, particularly those who hold some level of influence in their communities. Our data includes 15 cases of Uyghur religious figures who were detained when they were already over the age of 70 since 2014—including three over the age of 90. Suleyman Tohti, a well-known Uyghur molla from Kizilsu was reportedly detained in 2017, allegedly 86 years old at the time, and died in police custody.36The Turkish media report from the Uyghur media organization Istiqlal noted that he was 86 at the time of his death: https://shahit.biz/eng/viewentry.php?entryno=4792

These cases are consistent with reporting on detentions of elderly Uyghurs across the region, including the 78-year-old mother and 80-year-old father of World Uyghur Congress President Dolkun Isa—both of whom died after being sent to camps.37Radio Free Asia, “Targeted by Chinese Smear Campaign, Uyghur Leader Learns of Father’s Death,” Radio Free Asia, January 15, 2020, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/activist-father-01152020211855.html Another prominent case is that of 82-year-old Uyghur Islamic scholar Muhammed Salih Hajim, who first translated the Qur’an into the Uyghur language in a government-approved project and died 40 days after being detained in late 2017 or early 2018.38Radio Free Asia, “Uyghur Muslim Scholar Dies in Chinese Police Custody,” Rdio Free Asia, January 29, 2018, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/scholar-death-01292018180427.html Likewise, Uyghur writer Nurmuhammad Tohti, who was 70 years old and suffering from health problems at the time of his detention, died after being held in a camp for approximately five months.39Alison Flood, “Uighur author dies following detention in Chinese ‘re-education’ camp,” The Guardian, June 19, 2019,https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/jun/19/uighur-author-dies-following-detention-in-chinese-re-education-camp

Reasons for detention

The data we reviewed provide information on the basis for detention in 313 (30%) of total cases, regardless of whether the individual was imprisoned or detained. The most frequently cited reason for detention in camps and imprisonment is simply for “being an imam,” which may suggest that the testifiers who supplied the information may be speculating in some cases, given an understanding that any kind of religious affiliation may be grounds for detention.40Recent leaks from Aksu prefecture, reported by Human Rights Watch, confirm some of these suspicions. See Human Rights Watch, “China: Big Data Program Targets Xinjiang’s Muslims,” December 9, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/12/09/china-big-data-program-targets-xinjiangs-muslims. The “Qaraqash List” document also revealed that religious affiliations may lead to detention, though it was not the leading cause. See Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Ideological Transformation: Records of Mass Detention from Qaraqash, Hotan,” February 2020, https://docs.uhrp.org/pdf/UHRP_QaraqashDocument.pdf Likewise, many other entries did not include detailed information on the rationale for detention in camps, but given what we know about the detention of religious figures over time, we make the reasonable assumption that holding a current or past position as an imam fits the criteria. A secondary reason for camp detention relates to travel or communication abroad.

The data on prison sentences offer more clues about the basis for detention and sentencing. Many of the recorded charges are difficult to categorize as the substance of the charges overlap, but we have identified several general trends. Firstly, the most common category appears to be closely related to “illegal teaching,” “illegal preaching,” or “teaching religion to children” (61 cases, 30% of all charges)—something raised by several of the imams we spoke to in the diaspora. Efforts to break the links between previous generations’ religious knowledge have strengthened considerably since the 1980s. The data we reviewed suggest that this remains a particular strategy for the government. Other cases simply relate to the “religious affiliation” (50 cases, 25%) of the individuals, which can include “spreading religious propaganda,” “being an imam” and even simply having a religious education. Additional grounds for imprisonment include private acts like officiating or preaching at weddings (10 cases, 5%); praying (11 cases, 5%); travel or communication abroad (9 cases, 4%); and possessing or distributing “illegal religious materials” (7 cases, 3%).

Although the Chinese government often refers to the aforementioned behavior as “illegal” or “extremist,” the definitions of terms like these are ambiguous, likely by design.41A group of UN Special Rapporteurs and two Working Groups sent a letter to the Chinese government on November 1, 2019, expressing concern over the use of “extremism” and “terrorism,” stating that “[v]ague and arbitrary definitions raise concerns of the conflation of religious extremism and terrorism considering that many Uyghurs have been jailed and convicted on charges related to public displays of Uyghur culture or Islam more generally.” See UN Special Procedures Joint Other Letter to China, OL CHN 18/2019, November 1, 2019, https://spcommreports.ohchr.org/TMResultsBase/DownLoadPublicCommunicationFile?gId=24845 What is clear from the data is that Uyghur and other Turkic Islamic clergy have been sentenced to prison terms for behavior that does not come close to what might be considered “illegal” in any other jurisdiction. A cursory look at some of the details gives one an idea of what is considered “illegal” and worthy of a prison sentence:

- Three-year sentence for “Rejecting the Chinese government’s earthquake-resistant house-building projects.”

- Four-year, six-month sentence for “Religious extremism” for advocating for the separation of men and women at ceremonies like weddings.

- Five-year sentence for “not turning sickles, axes, and knives in to the village in a timely manner.”

- Five-year sentence for “conducting a marriage based on a false marriage certificate.”

- Seven-year sentence for “sending his child to Egypt to study [religion].”

- Eight-year, six-month sentence for “terrorism and extremism” for officiating a wedding in a mosque.

- Ten-year sentence for “praying in a group and reciting scripture.”

- Ten-year sentence for “distributing the recitation of scripture on memory cards.”

- Fourteen-year sentence for “watching a disc with religious extremist content.”

- Fifteen-year sentence for “helping children who studied illegally and for helping those who wanted to go abroad.”

- Seventeen-year sentence for “teaching others to pray and listening to tabligh [propagation of Islamic faith] on a memory card.”

- Twenty-year sentence for “studying for six months in Egypt, teaching children, and attempting to split the motherland.”

- Twenty-year sentence for “refusing to hand in his Quran book to be burned.”

- Twenty-five-year sentence “on the grounds that he did not prevent schoolchildren from entering the mosque, preaching and increasing the crowd.” The submitter testified that “He preached only with the help of books published with the permission of the Chinese government.”

- Life sentence for “spreading the faith and for organizing people.”

Although we could not independently verify the above cases, we find them consistent with the spike in prison sentences generally across the region, particularly sentences over five years.42See Chris Buckley, “China’s Prisons Swell After Deluge of Arrests Engulfs Muslims.” Buckley notes, “During 2017 alone, Xinjiang courts sentenced almost 87,000 defendants, 10 times more than the previous year, to prison terms of five years or longer.” For a more recent report on prison sentencing in the region, see also Maya Wang, “China: Baseless Imprisonments Surge in Xinjiang,” Human Rights Watch, February 24, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/02/24/china-baseless-imprisonments-surge-xinjiang Of the 304 cases that included data on the length of sentences, 96% included sentences of at least five years, including 25% of whom were sentenced for 20 years or more.

Case Study 1: Abidin Ayup

Abidin Ayup is a respected religious leader and former imam of the Qayraq Mosque in Atush for around 30 years, and worked as a professor at the Xinjiang Islamic Institute before retiring around 2000. He is over 90 years old.43Radio Free Asia, Ninety-Year-Old Uyghur Imam Confirmed Detained in Xinjiang But Condition Unknown, Radio Free Asia, January 22, 2020,

https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/imam-01222020130927.html

Available evidence shows that he was likely detained in a camp sometime between January and April 2017. A court document refers to him that he was detained for his religious background. The court verdict also indicated that he was already in poor health as of May 2017.44新疆维吾尔自治区克孜勒苏柯尔克孜自治州中级人民法敡刑 事 裁 定 书 [Kizilsu Kirgiz

Autonomous Prefecture Intermediate People’s Court Criminal ruling), July 1, 2019, archived at https://archive.fo/mNrdp

According to testimony to the Xinjiang Victims Database, he is presumably detained in Kizilsu.

Once favored, now threatened

Many of the imams in the dataset received government sanction to work in official religious capacities at some point in the years before the same government began harassing and detaining them. We counted 30 religious figures that testifiers explicitly mention were once officially approved by the government. However, given that the regional government mandated an approval process for all imams in the early 1990s,45Michael Dillon, Xinjiang—China’s Muslim Far Northwest (London: Routledge, 2004), p. 73. it is likely that the number of formally-approved religious figures is much higher. One imam from Kizilsu, for example, who was allegedly detained for refusing to drink alcohol, actually graduated from the Xinjiang Islamic Institute in 1998, and worked as a state-approved imam until 2014 or 2015. Another who graduated from the same institute in 2005 worked as an imam in Bayingolin prefecture, attended “patriotic education” courses in Korla and Ürümchi, and was said to have even been appointed the leader of an official Hajj trip to Mecca in 2016. He was arrested the following year and sentenced to 10 years in prison for being an “economic supporter” of terrorism for transferring money to a businessman who was later detained by the police on unclear charges.

Abduheber Ahmet—a state-approved imam favored by officials in Bayingolin prefecture—was sentenced to five and a half years in prison in 2017 for taking his son to a non-government-approved religious school five years earlier.

An imam from Ili prefecture, Aqytzhan Batyr, was also sent to a camp in 2018 before being sentenced to at least 17 years in prison in May 2019, possibly for visiting Kazakhstan.46Radio Free Asia, ”新疆塔城一伊斯兰教伊玛目被重囚十七年,” Radio Free Asia, September 25, 2019, https://www.rfa.org/mandarin/yataibaodao/shaoshuminzu/ql1-09252019064124.html The imam was quoted in Chinese media in 2016 saying, “We have truly realized the danger of illegal religion; we firmly stand against illegal religious activities. As a patriotic religious person, I will promote it and make sure religious people understand the harm of illegal religious activities and live a good life.”47Du Hong, “我县举办学习贯彻党的十八届五中全会、自治区党委八届十次全委(扩大)会议、地委扩大会议精神专题培训班” [Our county holds special training courses for studying and implementing the Fifth Plenary Session of the Eighteenth Central Committee of the Party, the Tenth Plenary (Expanded) Meeting of the Eighth Party Committee of the Autonomous Region, and the Spirit of the Expanded Meeting of the Prefectural Committee], Shawan News, February 23, 2016, archived at archive.is/fE0Go In another particularly egregious case, Abduheber Ahmet—a state-approved imam favored by officials in Bayingolin prefecture—was sentenced to five and a half years in prison in 2017 for taking his son to a non-government-approved religious school five years earlier. The local township’s Party Secretary told Radio Free Asia, “He took [his son] there so that his son would meet and play with other children,” and that he was given leniency in his sentence for admitting to it.48Radio Free Asia, “Xinjiang Authorities Jail Uyghur Imam Who Took Son to Unsanctioned Religious School,” Radio Free Asia, May 10, 2018, rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/imam-05102018155405.html

Charges for past behavior/actions

Another troubling trend in the data, reflected in Ahmet’s case, is the tendency for the government to imprison and sentence individuals retroactively for things that took place years prior and that the government had subsequently deemed “illegal.” Some of these cases involve Hajj pilgrimages (simply having gone on Hajj may put one in a high-risk category for detention),49Human Rights Watch, “China: Big Data Program Targets Xinjiang’s Muslims,” December 9, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/12/09/china-big-data-program-targets-xinjiangs-muslims as well as travel abroad in the past. Travel to certain “sensitive countries” has also been cited as a reason for detention in camps,50The countries are Afghanistan, Algeria, Azerbaijan, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Libya, Thailand, Malaysia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, South Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, Uzbekistan, and Yemen. See Human Rights Watch, “Eradicating Ideological Viruses,” September 2018, https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/china0918_web.pdf though it remains unclear how far into a person’s past the government might look for a justification for detention.

Several individual cases in the dataset also stand out, including:

- an imam who was sent to prison for “preaching in a cemetery 10 years ago”;

- an imam (now deceased) who was detained in 2014 for preaching at a wedding in 2010; and

- an imam from Ili prefecture who was said to have been sentenced to 20 years in prison for group prayer in 2009.

Sentences for “being an imam” also fit into the category of charges for past actions or behavior, given that “being an imam” could indicate that simply having been an imam at some point in the past may be grounds for detention or sentencing.

Guilt by association

Similar to the familial “circles” by which individuals are deemed threatening in the leaked Qaraqash Document,51The Qaraqash Document is a leaked documented dated to around June 2019 containing in-depth information about the familial and social circles of internees from eight neighborhoods in Qaraqash county, in Hotan prefecture. See Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Ideological Transformation”: Records of mass detention from Qaraqash, Hotan,” February 2020, https://docs.uhrp.org/pdf/UHRP_QaraqashDocument.pdf cases in the dataset also indicate that many have been detained simply for associations with “suspicious” figures like religious leaders. The role of guilt by association in the detention and sentencing of imams is further corroborated by Abduqeyyum, who noted in an interview, “Anyone with connections to me ended up detained”). Six cases in our dataset mention family or other relationships as grounds for detention in camps or prison, including a man whose father officiated a wedding, a man whose brother was an imam and traveled abroad, and two others who were detained as part of a larger “religious family.”

Researchers have shown the Chinese government has taken a vindictive, even vengeful, line against family members of the Uyghur community in the diaspora

Guilt by association and collective punishment are not new phenomena for Uyghurs, even for those residing abroad. Researchers have shown the Chinese government has taken a vindictive, even vengeful, line against family members of the Uyghur community in the diaspora—either for their activism, or simply for residing abroad.52Amnesty International (February 21, 2020). “China: Uyghurs living abroad tell of campaign of intimidation,” https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/02/china-uyghurs-living-abroad-tell-of-campaign-of-intimidation/. For earlier accounts of harassment and intimidation, see also Paul Mooney and David Lague “Holding the fate of families in its hands, China controls refugees abroad,” December 30, 2015, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/china-uighur/ Several of the imams we interviewed spoke in specific terms about the way in which the government targeted their family and even loose associates. The trend is all the more egregious given that the “charges” many Uyghur religious leaders face are either baseless or wholly disproportionate.

Case Study 2: Ablajan Bekri

Ablajan Bekri was the hatip (Friday imam) of the Qaraqash Grand Mosque and held multiple leadership positions in the government, including deputy chairman of the Qaraqash County Political Consultative Conference, vice president of the Hotan Prefecture Islamic Committee, and president of the Qaraqash County Islamic Committee.53Xinjiang Victims Database, Entry 10155: shahit.biz/eng/viewentry.php?entryno=10155

He was arrested in 2017 and sentenced to 25 years in prison for “violating the law,” but specific charges remain unclear. His case is included in the leaked Qaraqash Document, which mentions him 17 times in relation to other victims, many of whom were his students arrested for their relationship to him.54See Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Ideological Transformation,” Records of Mass Detention from from Qaraqash, Hotan, February 2020,

https://docs.uhrp.org/pdf/UHRP_QaraqashDocument.pdf According to testimony to the Xinjiang Victims Database, he is presumably detained in Ürümchi.

Notes on compilation of data

As a product of some of the research limitations outlined in Section II. (pp. 8–11), the dataset presented must be understood in the context of the many unknowns about the situation in East Turkistan today—from the implementation of policies by the regional government to the impact on individuals registered in the dataset.

The dataset is derived primarily from four sources: (1) the Uyghur Transitional Justice Database (UTJD);55Uyghur Transitional Justice Database: www.utjd.org (2) the Xinjiang Victims Database (Shahit.biz);56Xinjiang Victims Database: https://www.shahit.biz/eng (3) data compiled in the diaspora by Uyghur scholar and researcher Abduweli Ayup;57Uyghur scholar and researcher Abduweli Ayup has been able to track down an extensive list of detained imams through various public and private sources beginning in 2018. These sources include direct contacts, leaked documents such as the “Qaraqash List” and the “Aksu List,” and from scouring Chinese government websites. His organization, Uyghur Yardem, based in Norway, conducted interviews with Uyghurs in Istanbul between December 2019 and May 2020 and compiled a list of 4577 cases of detention in prison or camps. and (4) information gleaned from additional open-source materials online.58These sources include the Congressional Executive Commission on China’s political prisoner database, reports from journalists, and other sources.

Although evidence collected in several public and private databases shows many Uyghurs have been detained in camps or given prison sentences for “teaching Islam to children,” these cases lie outside the ambit of the report, which focuses on individuals who served as religious leaders in both official and unofficial capacities. Cases that involve the charge of “teaching Islam to children” remain in the current dataset, however, if they have been expressly identified as religious figures by testifiers.

The list we compiled of those detained, disappeared, or sentenced is by no means exhaustive. Though our conclusions are based on a dataset which has been compiled as thoroughly as possible, we recognize the pitfalls of the source of the data, which in this case is second-hand information submitted primarily by members of the Uyghur diaspora. The Uyghur diaspora are typically the only sources able to gather information, albeit limited, about their family and friends in East Turkistan. We have taken steps to corroborate this information, which we describe in further detail below.

The fluidity of the situation on the ground may further affect the authenticity of the source data. Many of the cases have been reported since 2017, and given that communication in and out of East Turkistan remains very difficult, it is often difficult to ascertain whether some may have been released from camps since their initial detention. Although there is some evidence that a small proportion of the interned population has been released, releases are likely not widespread. As one database source has noted, “Contrary to claims by the regional authorities that the detainees have been released, we have only observed a very small number of confirmed releases.”59Uyghur Transitional Justice Database: www.utjd.org We have chosen to leave 10 “release cases” in our dataset, given that many have been released and subsequently re-arrested, and because they provide clues for reasons the authorities gave for detaining these individuals.

A third hurdle is the paucity of information contained in the submissions or the compilation of the data itself. Although the cases contain enough information to make a reasonable assessment of various trends, many case details are either missing or uncertain. Nevertheless, all 1,046 cases include a name, occupation, and gender (100%); 925 (88%) include the prefecture; 668 (64%) include information about status at the time of reporting (prison, camp, released, house arrest, deceased); 601 (57%) include information about the month or year of detention or disappearance; 595 (57%) include the birth year; 313 (30%), the reason for detention or sentencing; 247 (24%), the place of detention or sentencing; and 186 (18%), information about the mosque where the religious figure was once affiliated.

As a result of these unknowns, we have taken steps to corroborate the data where possible, through cross-referencing entries with multiple testimonies and with reporting by investigative journalists and researchers. Of all of the cases in the dataset, 105 were attested to by at least two sources, while the remainder were submitted by just one source. We acknowledge that multiple testimonies about the same individual from different databases and other sources may have been submitted by a single source in some cases.

Despite these limitations, we consider the compiled data the most authoritative account of Uyghur clergy detained since around 2015, given that no other studies have attempted to assess this form of detention.

To address the lack of direct corroboration in some cases, we compared prefectural detention rates in our dataset with the percentage of Turkic peoples of the entire region (Uyghur, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Uzbek, Tatar) living in each prefecture.60These figures are based on the 2018 Xinjiang Statistical Yearbook. The percentages of those detained in nearly every prefecture from our dataset align relatively closely with Turkic peoples residing in each prefecture as a percentage of the total regional Turkic population. This tells us that the compiled cases are at least comparable to what one might expect if a similar proportion of Turkic peoples were detained across the entire region. For example, 14.7% of the individuals in our dataset (of the cases which include residence data) reside in Ili, whereas the Turkic population makes up 15.6% of the total regional Turkic population. Similarly, 4.4% of our dataset is made up residents of Kizilsu, whereas the prefecture makes up 4.3% of the regional total of all Turkic peoples. One noticeable outlier was Kashgar prefecture, which makes up 16.9% of our data, in contrast to the Turkic population making up 32% of the total across the region. These lower statistics may be a result of heavier security measures in Kashgar, and the reduced ability of the Uyghur population to communicate outside the prefecture and the region.

Despite these limitations, we consider the compiled data the most authoritative account of Uyghur clergy detained since around 2014, given that no other studies have attempted to assess this form of detention. We have done our best to offer this information with as much transparency as possible, while ensuring Uyghurs in East Turkistan and abroad are kept safe from retaliation. For this reason, we have chosen not to release the dataset to the public. These detention rates should not be construed as a representation of broader trends for all Turkic peoples in the region, given that religious figures have been targeted more aggressively by the government—even before 2015. Detention rates among Uyghur clergy might be comparable to the detention of the intellectual class, who have been targeted for their influence within society.61Uyghur Human Rights Project, “UPDATE – Detained and Disappeared: Intellectuals Under Assault in the Uyghur Homeland,” May 21, 2019, https://uhrp.org/report/update-detained-and-disappeared-intellectuals-under-assault-in-the-uyghur-homeland/

IV. Contemporary Religious Practices

While Uyghur Islamic practice has transformed considerably over time, CCP policies since the 1990s have markedly altered the range of acceptable (and “legal”) religious practice and expression.

In recent decades, and in spite of many restrictions, Uyghurs have typically practiced a form of Sunni Islam. While a majority of Uyghurs consider Islam as an integral part of their cultural identity, some lead more religious lives and others more secular ones.

Uyghur neighborhoods and villages have traditionally had a local mosque, where imams lead five daily prayers and deliver sermons, though a campaign to demolish or significantly alter these structures has been underway since at least 2016.62Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Demolishing Faith”; Australian Strategic Policy Institute, “Cultural erasure.” Older men would participate most consistently in the call to prayer, and outside city centers it was also common to see young men taking breaks from work, alone or in small groups, to pray at the proper times. Women who participate generally pray in private, and because of government restrictions since the 1990s, children under 18 are not allowed to enter mosques or participate in religious activities.63The history of religious repression is explored in detail in Section V.

Although imams were once selected by their own local communities and congregations, oversight for the training of imams in East Turkistan is now the exclusive responsibility of the state-run Islamic Association of China (IAC)—the body now overseen by the United Front Work Department responsible for administering CCP policy relating to Islam. Rather than providing a substantive religious education, the IAC aims to ensure loyalty to the CCP and manage the relationship between clergy and worshippers. According to the now-defunct State Administration for Religious Affairs (SARA), the primary qualification for state approval was that imams “love the motherland, support the socialist system and the leadership of the Communist Party of China, comply with national laws, [and] safeguard national unity, ethnic unity, and social stability.”64Congressional-Executive Commission on China, “CECC Annual Report 2012http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG112shrg76190/pdf/CHRG-112shrg76190.pdf,” October 2012, https://www.cecc.gov/publications/annual-reports/2012-annual-report

Until 2017, there was only one officially sanctioned madrasafor training religious professionals in the entire region—the Ürümchi-based Xinjiang Islamic Institute, which includes the Xinjiang Islamic Scripture School. Faculty are government employees, and the institute’s curriculum is overseen by the CCP through the United Front Work Department. Since 2017, the regional government reportedly set up eight branches of the institute across East Turkistan for training religious clerics, likely as a means of more closely monitoring activities of Uyghur religious leaders and students. In order to qualify as an official imam and carry out the related duties, all candidates are required to graduate from one of these CCP-sanctioned institutes.65Liu Xin, “Islamic school in Xinjiang offers anti-extremism courses to imams,” Global Times, July 25, 2018, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20210409211226/https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1112288.shtm

Aside from strictly controlled religious activity at the mosque led by state-appointed imams, some Uyghurs also pray at mazars, Sufi shrines to Muslim saints that often consisting of a tomb to historic Uyghur figures which serves as a destination for pilgrims. Uyghur folklorist Rahile Dawut, who conducted extensive research on Uyghur religious culture and folklore until her disappearance in December 2017,66Chris Buckley and Austin Ramzy, “Star Scholar Disappears as Crackdown Engulfs Western China,” New York Times, August 10, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/10/world/asia/china-xinjiang-rahile-dawut.html has noted that “[m]azar combines religious elements of Islam—by being ideologically based on worshipping Muslim saints—and elements rooted in popular beliefs with their orientation on pursuing ‘this-world-benefits.’”67Rahile Dawut, “Shrine Pilgrimage and Sustainable Tourism,” in Situating the Uyghurs Between China and Central Asia, ed. Bellér-Hann et al. (Aldershot, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2007). Scholar Rian Thum calls the mazar “a point on the landscape that holds particular numinous authenticity, a connection to and presence of the divine that surpasses the sacredness even of the mosque as a physical structure.”68Rian Thum, “The Spatial Cleansing of Xinjiang: Mazar Desecration in Context,” Made in China Journal, August 24, 2020, https://madeinchinajournal.com/2020/08/24/the-spatial-cleansing-of-xinjiang-mazar-desecration-in-context/ Since 2017, the shrines themselves have been systematically destroyed or desecrated by Chinese authorities, after many were gradually closed to pilgrims altogether over the last three decades.69Ibid. Shrine pilgrimage—like many other Uyghur religious practices—has been deemed “illegal religious activity” and prohibited.70Rachel Harris, “Uyghur Heritage and the Charge of Cultural Genocide in Xinjiang,” Newlines Institute, September 24, 2020, https://newlinesinstitute.org/uyghurs/uyghur-heritage-and-the-charge-of-cultural-genocide-in-xinjiang/

The most common religious observance among Uyghurs is refusal to eat foods that are non-halal (forbidden in Islam), such as pork. Uyghur restaurants in East Turkistan serve halal fare, and Uyghur people typically eat only at restaurants that serve such food. An official “anti-halal” campaign began in 2018, however, as officials in Ürümchi called on local officers to strengthen the “ideological struggle” and fight “halalification” in the region.71Lily Kuo, “Chinese authorities launch ‘anti-halal’ crackdown in Xinjiang.”

Uyghurs also celebrate holidays that reflect Islamic, Turkic, and Persian influences, including Roza Héyt (Eid al-Fitr), Qurban Héyt (Eid al-Adha), Nowruz (Persian New Year), and Barat, a holiday involving a prayer vigil in the month before Ramadan. Other Uyghur religious celebrations feature practices led by imams, who preside at weddings (toys), circumcision ceremonies (sunnet toys), and funerary meals (nezirs). The celebrations variously entail prayer, oil sacrifice, animal sacrifice, and/or communal meals, and may be large-scale events with many in attendance. Mounting restrictions on these celebrations and life-cycle events have been documented.72Timothy Grose, “How the CCP Took over the Most Sacred of Uighur Rituals,” ChinaFile, December 9, 2020, https://www.chinafile.com/reporting-opinion/viewpoint/how-ccp-took-over-most-sacred-of-uighur-rituals

Many of these practices, rituals, and celebrations offer a glimpse into how Islam has colored and shaped Uyghur life, particularly over the past several decades. It is difficult, however, to capture just how quickly regional authorities have suppressed them over the same period. Although Uyghur religious figures are now facing an exceptionally restrictive, if not totalitarian, environment, a cyclical pattern of accommodation and repression has played out through the course of the region’s history, which is helpful in understanding how the situation got to where it is today.

V. Uyghur Religious History

Today, a majority of Uyghurs see Islam as a central aspect of their identity, though Uyghur identities drawing on Islam (as all other identities) are highly complex, deeply entwined with ethnic and cultural identities influenced by shared histories and by internal and external factors over time. According to scholars, Uyghurs today might identify their ethnicity in terms of no fewer than five separate components “with varying degrees of salience for specific individuals in particular circumstances.”73Graham Fuller and Jonathon Lipman, “Islam in Xinjiang,” p. 338. See also Dru Gladney, “Relational alterity: Constructing Dungan (hui), Uygur, and Kazakh identities across China, Central Asia, and Turkey,” History and Anthropology, 9 (4), 445–77.

Scholars contend that prior the arrival of Qing troops in the region in the 18th century, Uyghurs held “common cultural assumptions, patterns of social interaction, religious practices and moral values, a shared history, and an attachment to the land.”74Joanne Smith Finley, The Art of Symbolic Resistance: Uyghur Identities and Uyghur-Han Relations in Contemporary Xinjiang (Leiden: Brill, 2013), pp. 4–5. In any case, shared religious beliefs among Uyghurs represent a primary defining feature today—one that is not easily dislocated.

The relative geographic isolation of East Turkistan over time also played a role in the development of unique local Islamic and folk-religious practices of the region,75For an overview of Uyghurs’ historical religious practices and identity formation over time, see Rian Thum, The Sacred Routes of Uyghur History (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2014). but diversity within the region has long existed, as well. As Justin Rudelson notes, “In Xinjiang, this diversity was fostered throughout history by the great distances separating the oases from one another.”76Justin Rudelson, Oasis Identities: Uyghur Nationalism Along China’s Silk Road (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997), p. 24. Such religious diversity still exists today. As such, the people living in East Turkistan have a diverse religious history marked by practice of Buddhism, shamanism, Manichaeism, and Nestorian Christianity, prior to converting to Islam between the tenth and fifteenth centuries.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were a dynamic period for religion in East Turkistan, as Uyghurs and others in the local Muslim populations practiced religion mostly unfettered, and were able to travel to other regions of Central Asia and beyond for additional religious education. Uyghurs continued to develop and utilize distinct education systems, influenced most notably by the Jadidist (new method education) movement—a Muslim reformist movement spreading across Central Asia in the late 19th century. The Jadidist movement’s influence in the region “rejected traditional canonical learning in favor of personal and national strengthening through modern education,”77Nabijan Tursun and James Millward, “Political History and Strategies of Control, 1884-1978,” in Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Borderland, ed. Frederick Starr (New York and London: M.E. Sharpe, 2004), p. 73. as its methods combined religious education with modern studies of literature, history, math, and science.78Sean Roberts, The War on the Uyghurs: China’s internal campaign against a Muslim minority (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020), p. 31. Many of the Uyghurs who absorbed Jadidist thinking in the 1920s would later become involved in independence movements in the 1930s.79Joanne Smith Finley, The Art of Symbolic Resistance, p. 16–17.

Alongside schools set up by Jadidists, Islamic education was available to boys between the ages of 6 and 16 (and in some places to girls under 12) via the traditional institution of the maktap, informal schools at the mosque, teacher’s homes, or wealthy community members’ homes.80James Millward, Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), p. 146. As Linda Benson writes of the educational opportunities at the time, “Local schools that only provided religious education were called in Uyghur ‘kona mektep,’ while schools offering a partially secular education were referred to as ‘yengi mektep.’”81Linda Benson, “Education and Social Mobility among Minority Populations,” in Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Borderland, ed. Frederick Starr (New York and London: M.E. Sharpe, 2004), p. 192. The curriculum, taught by an imam, was primarily religious and included instruction on religious festivals, Quranic verses, and some poetry. The larger oases of southern East Turkistan also supported madrasas, colleges attached to shrines and run as charitable foundations, of which there were dozens through the early 20th century.82Millward, Eurasian Crossroads, pp. 146–48.

The early Republican period, following the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1912, would make little practical difference in the lives of Uyghurs as space remained open for some Islamic practices and local customs. This space began closing by the late 1920s, however, with the appointment of leaders less attuned to local grievances. Some Islamic practices were curtailed, including a ban on Hajj pilgrimage for local residents, and resistance emerged in Qumul and Hotan, leading to the establishment of the short-lived First East Turkistan Islamic Republic (1933–34). In the aftermath, the new leader in the region, warlord Sheng Shicai, took some steps to appease the local population, providing grain and monetary stipends to thousands of middle and low-ranked Islamic clergy, and allowing the Islamic court system to operate in parallel to the Chinese system in civil and minor criminal cases.83Millward, Eurasian Crossroads, p. 247.

Despite moderate accommodationist policies, some religious practices were still constrained out of fear that allowing the people to practice religion might lead to revolt. Nevertheless, the Second East Turkistan Republic emerged out of continued discontent with Chinese rule, beginning with a rebellion in the Ghulja region, supported by the Soviets. In the Second ETR (1945–49), Uyghur and Kazakh leaders exercised de facto control over Ghulja and were included in a coalition government with the Guomindang in Ürümchi. As Sean Roberts points out, “In many ways, the Xinjiang coalition government . . . represented the most accommodating administration to the region’s local Muslim population in modern history, including to this day.”84Roberts, The War on the Uyghurs, p. 41.

Uyghurs and the local population experienced greater suppression of Islamic practice once again following the CCP occupation of East Turkistan in 1949. Restrictive policies were largely derived from the Marxist-Leninist approach of the CCP, which viewed religion as undesirable and “a potential source of political opposition and weakening influence on the socialist state.”85Stephen E. Hess, “Islam, Local Elites, and China’s Missteps in Integrating the Uyghur Nation,” USAK Yearbook of International Politics and Law, 3 (2010): pp. 407–30. Similar to historical anxieties among rulers over time, the CCP regarded the role of religion and religious leaders as possible threats to Party rule because of their ability to unify and mobilize large segments of the population.86Ibid., p. 411. Scholars argue that Islam, and by extension, Islamic teaching, was (and remains) branded “a reactionary ideology and feudal throwback, at best a backward aspect of human society doomed to wither with progress and the advance of science.”87Graham Fuller and Jonathon Lipman, “Islam in Xinjiang,” p. 332.

H.H. Lai provides a useful framework for understanding changes in policy towards religion in China beginning around this period: “cooption” (1949–57), “vacillation” (1958–65), “prohibition” (1966–79), and “calculated monopoly” (post-1979). In the early- to mid-1950s, the Party-state provided some space for Islamic practice, allowing imams to retain their positions (albeit under strict control) and permitting Uyghurs to occupy positions that had been restricted to Han Chinese.88Rian Thum, “The Uyghurs in Modern China,” Oxford Encyclopedia of Asian History (2018), https://oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277727-e-160 It was during this time, though, that the Party-state began to play an early role in codifying which elements of Islam were to be considered legal and legitimate. As noted by Rian Thum, in contrast to previous periods “the Communists aimed to replace the [Islamic court] system wholesale with state institutions” and “integrated religious institutions into a state-managed system, providing funding from government coffers, albeit at drastically lower levels.”89Ibid.

In 1956, the Hundred Flower Movement invited criticism of the Party, and many Uyghurs spoke out against unfair treatment. In the anti-Rightist campaign that directly followed in 1957, those who had voiced complaints were targeted with arrest, especially Islamic leaders.90Nabijan Tursun and James Millward, “Political History and Strategies of Control, 1884–1978,” in Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Borderland, ed. Frederick Starr (New York and London: M.E. Sharpe, 2004), pp. 92–93. The CCP’s official Religious Reform Campaign simultaneously began the process of completely dismantling all Uyghur religious institutions and practices.91Rian Thum, “The Uyghurs in Modern China,” p. 13.

Collectivization policies during the Great Leap Forward (1957–62) turned over mosque lands to the state, banned mazar festivals, and made Islamic practice nearly impossible. Repression would accelerate during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76). As James Millward writes:

“There are many reports of Qur’ans burnt; mosques, mazars, madrasas and Muslim cemeteries shut down and desecrated; non-Han intellectual and religious elders humiliated in parades and struggle meetings; native dress prohibited; long hair on young women cut off in the street.92Millward, Eurasian Crossroads, p. 275.“

A surprising number of these examples are conspicuously present in the CCP’s approach to Islam and Uyghurs today.

Edmund Waite explains that in response to this period, many Muslims adapted Islamic rituals so that laymen in the household might perform them hidden from the gaze of outsiders, which shifted religious teaching and practice into a less formal household role, subverting state control.93Stephen Hess, “Islam, Local Elites, and China’s Missteps in Integrating the Uyghur Nation,” Journal of Central Asian and Caucasian Studies, 4:7 (2009), p. 87. Many of these acts of resistance echoed into the 1990s and 2000s.94Smith Finley, The Art of Symbolic Resistance. In interviews with UHRP, Uyghur imams in the diaspora recounted that the period following the Cultural Revolution was a time of relative openness, a move to accommodation in the accommodation-repression cycle. However, the state moved back toward repression as Uyghurs attempted to exercise forms of civil resistance throughout the 1990s and 2000s.

We know that Uyghurs employed a number of creative methods to continue passing on religious knowledge to younger generations during the Cultural Revolution, either through private teaching or from sheer memory and often at great personal risk. Researchers have written less about more recent forms of resistance, particularly in the form of private religious transmission.

In interviews with UHRP, Uyghur imams in the diaspora recounted that the period following the Cultural Revolution was a time of relative openness […]

The period of religious revival that began in the 1980s provides us with an ideal starting point to present the stories of five Uyghur imams who grew up in the latter part of the Cultural Revolution and experienced this revival first hand. The following section presents their stories, which we contextualize using extant scholarship, ultimately illustrating how the state came to adopt the repressive policies we are witnessing today.

VI. Imams Speak of Openness, Renewed Restrictions